eBook - ePub

American Egyptologist

The Life of James Henry Breasted and the Creation of His Oriental Institute

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

American Egyptologist

The Life of James Henry Breasted and the Creation of His Oriental Institute

About this book

James Henry Breasted (1865–1935) had a career that epitomizes our popular image of the archaeologist. Daring, handsome, and charismatic, he traveled on expeditions to remote and politically unstable corners of the Middle East, helped identify the tomb of King Tut, and was on the cover of Time magazine. But Breasted was more than an Indiana Jones—he was an accomplished scholar, academic entrepreneur, and talented author who brought ancient history to life not just for students but for such notables as Teddy Roosevelt and Sigmund Freud.

In American Egyptologist, Jeffrey Abt weaves together the disparate strands of Breasted's life, from his small-town origins following the Civil War to his evolution into the father of American Egyptology and the founder of the Oriental Institute in the early years of the University of Chicago. Abt explores the scholarly, philanthropic, diplomatic, and religious contexts of his ideas and projects, providing insight into the origins of America's most prominent center for Near Eastern archaeology.

An illuminating portrait of the nearly forgotten man who demystified ancient Egypt for the general public, American Egyptologist restores James Henry Breasted to the world and puts forward a brilliant case for his place as one of the most important scholars of modern times.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access American Egyptologist by Jeffrey Abt in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

eBook ISBN

9780226001128Subtopic

Education Biographies1

Equipment for a Great Work

Pharmacist, Minister, Egyptologist

The third of Charles and Harriet Breasted’s four children, James Henry was an active and inquisitive youngster. He grew up fishing and camping, and he played sports, including baseball, with abandon. His “catching pitched balls without a mask” resulted in his nose being broken in two places, injuries that remained faintly evident for the rest of his life. Around the age of five he somehow learned of a nearby school he wanted to attend. Overcoming his mother’s objections that he was too young, Breasted began at “Mrs. Squire’s School—a single room in a stone house above the Rock River,” named for the elderly woman who ran it. He remembered Rockford as a “very pious town,” an impression reinforced by his religious upbringing. Sunday school was “one of the greatest things” of Breasted’s life, and many years later he recalled “so well the stories—they were really history—of the Bible lands” to which he owed “an immeasurable amount of inspiration.”

Charles Breasted, who began his work life as an apprentice to a “master tinsmith,” became a successful merchant in Rockford and then established a large hardware store in downtown Chicago. He was poised for considerable prosperity when he lost the store in the 1871 Chicago fire. The devastation reduced him to the station of a traveling salesman for the Michigan Stove Company, a loss of independence, stature, and income that deeply affected his outlook and health. In 1873 he moved the family to Downers Grove, Illinois, then a small town just over twenty miles southwest of Chicago, to be closer to the train network that connected him to his territories in Illinois and Wisconsin. He built a home on a seven-acre property the family called “The Pines,” from which many of “Jimmy” Breasted’s earliest memories derived: raising asparagus to market in Chicago; milking cows; collecting birds’ eggs, butterflies, and coins; and handcrafting furniture. He also took up drawing around this time, apparently with the intent of augmenting his collections with drawings of “animals and objects.” He drew a variety of subjects from about his twelfth year on, launching a lifelong interest in developing his observation skills as well as his lettering and rendering ability. A nearby train station, where an engineer invited Breasted to ride in a locomotive cab, inspired his first ambition, to become a railroad engineer.1

For many summers, from his childhood through his midtwenties, Breasted returned to Rockford, where he stayed with a close family friend of both his father’s and mother’s families, Theodocia Backus, or “Aunt Theodocia.” By then a widow of modest means, she nonetheless devoted herself to his success. The summers he spent with her were filled with “grooming Dobbin, her carriage horse, mowing lawns, running errands, pumping the church organ, singing in the choir, and [assisting her] in a multitude of other thoughtful ways.”

But Breasted was also mischievous. He could “throw snowballs with fiendish accuracy, especially at top hats on Sundays”; he had a “genius for inflicting enraging penalties upon mean or unkind neighbors”; and during his teenage years he staged a prank that entered the family annals. He and a friend found a section of wooden conduit that they persuaded a local blacksmith to cap at one end and reinforce with metal straps every few inches. They outfitted it with a mount and wheels, transforming the thing into a formidable-looking toy cannon that became genuinely dangerous when they discovered that wooden croquet balls fit the barrel perfectly. They saved their pennies, purchased containers of gunpowder and fuses, and introduced their ordnance early on the Fourth of July in Rockford’s courthouse square. They set off a few harmless blasts, rousing neighbors, before a final shot blew out a window in a nearby house and the cannon recoiled, scattering an angry crowd that was gathering. Breasted confessed his part in the mayhem to Backus, who, though a deeply moral woman, usually found his antics humorous. She soothed Rockford’s peeved citizens, paid for damage wreaked by the fusiliers, and attempted to sternly admonish her playful charge.

At a young age Breasted acquired a passion for books, nurtured by his father, who read aloud to him such works as Dickens’s Pickwick Papers and Master Humphrey’s Clock. Though not formally educated, Charles Breasted assembled a modest library, where his son discovered such childhood classics as Robinson Crusoe and The Swiss Family Robinson. The boy became a voracious reader, silently moving his lips as he read—a habit he never lost—and grew into more challenging works by Plutarch, Shakespeare, and Vasari. Particular favorites included James Fenimore Cooper’s The Last of the Mohicans and Richard F. Burton’s multivolume Arabian Nights, though he must have read the latter in his twenties because it was first published between 1885 and 1888.

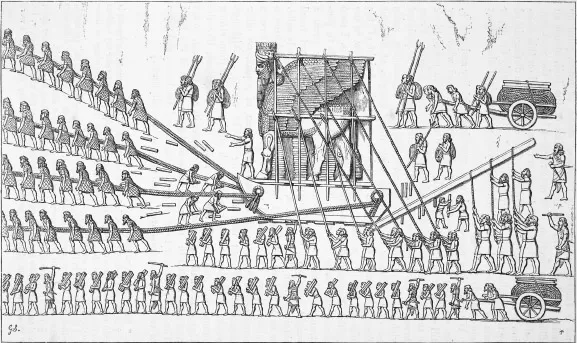

Fig. 1.1 Layard, Discoveries in the Ruins of Nineveh and Babylon (1859), 113. Public domain, reproduction by author.

Among the readings of Breasted’s youth was his father’s copy of Austen Henry Layard’s Discoveries in the Ruins of Nineveh and Babylon. Published in 1859, it recounts Layard’s expeditions and finds, including the monumental winged bulls now displayed in the British Museum. The hefty, nearly seven-hundred-page book, written expressly for popular consumption, is richly illustrated with maps, the plans of ancient temples, engravings of everything from pottery to bas-reliefs, and tables of cuneiform inscriptions (figure 1.1). But among the Breasteds’ books, the Bible was far and away their favorite and most frequently read text. It was also the preeminent source of ideas and values that each of them, including James, quoted as they navigated the challenges of modern life.2

Breasted felt his “early ‘education’ was wholly haphazard and without pattern.” After Mrs. Squire’s School in Rockford, he attended a “two-room red brick” school near his family’s home in Downers Grove until September 1880, shortly after he turned fifteen. About that time, having graduated from high school, he became interested in North-Western College, located in Naperville, Illinois, about seven miles west of his home. The college’s appeal was due to a “scientific exhibition” mounted by a professor of natural sciences that made a “profound impression . . . upon [Breasted’s] youthful but highly receptive mind.” He enrolled in the college and flourished. Years later a classmate recalled that Breasted

soon won his way into the hearts of his fellow students and won the confidence of the faculty who looked upon him as an ideal student looking forward to a brilliant career. He had a wiry makeup always bubbling over with energy, he was always neat in appearance and profoundly impressed us with the loftiness of his . . . ideals. Although he was one of the youngest members of the class he taught us the art of studying. He was interested in the deeper aspects of Nature as revealed by science and mathematics. He never regarded an assignment met until he had thoroughly mastered it. In mathematics he often wrote out . . . full demonstrations which staggered the other members of his class. While some . . . were content to give an approximate translation of a passage in the ancient classics he never passed it by until he had rendered it into immaculate English. Even we neophytes listened with intense pleasure to his recitations.

Despite his apparent robustness, Breasted was “troubled by a serious illness” in early spring 1881 and dropped out of school for a brief time. Instead of returning to North-Western after his recovery, however, he pursued an “apprenticeship in pharmacy” that he thought might advance his longer-term “ambitions in chemistry or botany.” During 1882–83 he enrolled at the Chicago College of Pharmacy and did some pharmacy clerking on the side, first in his brother-in-law’s business in Rochelle, Illinois, about six miles south of his family’s earlier home in Rockford, and then back in Downers Grove.

By fall 1883, he returned to North-Western, picking up where he’d left off in the “Latin & Scientific Course,” now with the notion of specializing “solely in literature.” He remained there until spring 1885, shifting at some point to the “Classical” department with a concentration in Latin. Breasted took more courses in mathematics, the natural sciences, and philosophy, as well as one in “Surveying” and another intriguingly titled “Comics.” He spent his summers working in a “small country bank,” where he acquired bookkeeping skills as his responsibilities grew from back-room clerking to window teller.

He also found time in the summer of 1884 to visit family on the East Coast, a trip that took him through Washington, DC. His letters home, teeming with descriptions of scenic vistas and stimulating conversations, reveal his growing observational skills and ability to write vivid narratives rich with detail and nuance. While in Washington, Breasted made the usual tourist stops. Among them, the US Patent Office building’s extensive “model rooms” filled with miniatures of inventions impressed him the most. After describing their size and number and the cases in them, he continued: “Every shelf is filled with models. It would take a lifetime to see them all. All models of the same kind are placed together, that is reapers with reapers & scales with scales. Being curious I counted the number of different models of patent fruit jar-covers, with which one shelf was full, & found there were 246.”3

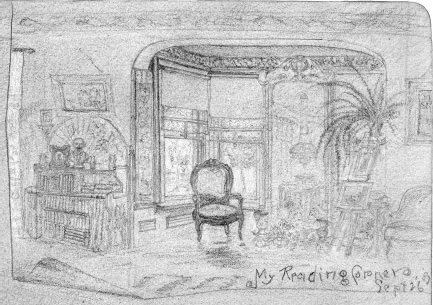

Fig. 1.2 Breasted’s pencil drawing, “My Reading Corner,” 26 September 1887. Courtesy of the Oriental Institute, University of Chicago.

In fall 1885 Breasted had another change of heart, returned to the Chicago College of Pharmacy, and completed his pharmacy degree the following spring. His brother-in-law, who now had a business in Omaha, Nebraska, invited Breasted to work there as a pharmacist. He settled into the new job by fall but lasted only through early spring 1887, when he returned to Downers Grove at his family’s behest. Perhaps his brother-in-law’s religious laxity, such as selling cigars on Sunday, contributed to Breasted’s return. He looked for work around Downers Grove without success, began exploring the purchase—with his father’s assistance—of a pharmacy in a nearby town, and was about to acquire a drug store in Chicago when he suddenly fell ill again. Breasted convalesced the following summer and early fall in Rockford with Theodocia Backus, whiling away his time drawing and reading (figure 1.2). Her care included the spiritual as well as physical, and when Breasted returned home in October 1887, it was with an entirely new vocation in mind.4

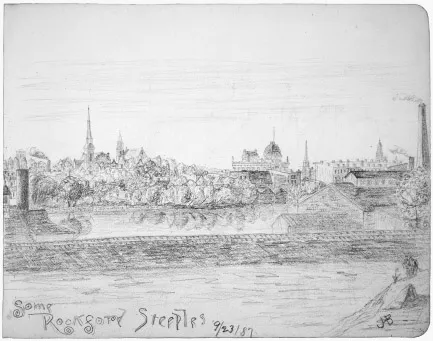

Aunt Theodocia and her husband were Seventh-Day Adventists, but after he died, she became a Congregationalist, the denomination in which Breasted was raised. The Congregationalist Church was among the more liberal American Protestant denominations, deeply engaged in social action by the 1880s and striving to become a “non-sectarian” community, “a union of Christians who are not asked to renounce their previous denominational teachings but . . . to join in a simple covenant pledging cooperation and fellowship.” Yet Backus remained faithful to the more conservative values of the Seventh-Day Adventists, and she had the zeal of a proselytizer, too, seizing the opportunity of Breasted’s care to steer him toward what she believed was his true calling: a Christian ministry. She counseled him on questions of personal morality and faith and encouraged his attendance at church and at least one tent-revival gathering—then a popular means of rallying the faithful. Backus’s attentions were effective and even show up in Breasted’s drawings from the time (figures 1.3 and 1.4). Thus primed, Breasted attended a life-changing meeting at the Downers Grove Congregational Church, where, Breasted wrote, “President Fiske of [Andover] Theological Seminary . . . forcefully said something about striving for high goals, about relentlessly making one’s ambition go ‘up—up—UP.’ . . . The way in which he separately emphasized those three words impressed me more than anything else had.” Around this time, Breasted recalled, “it suddenly flashed into my mind as if conveyed by an electric spark, that I ought to preach the gospel.” But the decision did not settle easily: “I fought all this for nearly two weeks . . . with every power and faculty within me, but . . . finally I gave up. . . . Then came a struggle such as I have never dreamed of; . . . to tear out selfish ambition and ride down worldly desires. I was in a wild tumult, . . . like a tree bending to the ground before a mighty wind. But the calm came; and now . . . what have been my dearest hopes are dead ashes and out of them has sprung a new, a holier ambition.”

In late October 1887, and now just over twenty-two years old, Breasted began taking classes in Hebrew and Greek, probably on a part-time, nonmatriculated basis, at the Chicago Theological Seminary, then located by Union Park on Chicago’s near west side. It was affiliated with the Congregationalists and often referred to as the “Congregational Institute” or “Union Park Theological Seminary.” Breasted was proud he could attend at no cost to his parents, but even so, they sold their property in Downers Grove and took an apartment near the seminary to remain near him. Meanwhile, Breasted had yet to complete his baccalaureate work at North-Western. He apparently tied up the loose ends during 1887–88 while also taking classes at the seminary. For some reason, however, he did not receive the North-Western degree until 1890.5

Of Breasted’s seminary professors, one, Samuel Ives Curtiss, was especially influential. Curtiss was among the many Americans who, lured by the high intellectual standards and scholarly accomplishments of German universities earlier in the nineteenth century, crossed the Atlantic to pursue advanced training, earning a doctorate at the University of Leipzig in 1876. He studied with Franz Delitzsch, a Lutheran theologian and expert Hebraist of Jewish descent who is credited with helping develop the Higher Criticism in Old Testament studies. Some trace the origins of the Higher Criticism to the comparative, “literary-historical”—as distinguished from canonical or devotional—studies of the New Testament introduced by Erasmus. With the refinement and increasingly systematic application of these methods in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, the stage was set for scholars of Delitzsch’s generation to begin using the techniques to disentangle the sources and chronological sequence of the most ancient of Old Testament writings: the Pentateuch.

Fig. 1.3 Breasted’s pencil drawing, “Some Rockford Steeples,” 23 September 1887. Courtesy of the Oriental Institute, University of Chicago.

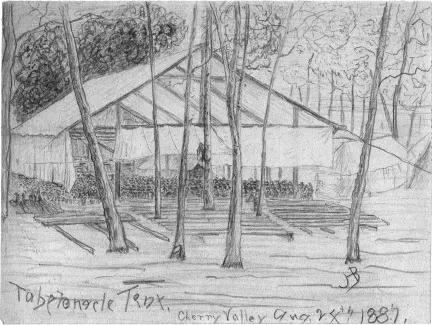

Fig. 1.4 Breasted’s pencil drawing, “Tabernacle Tent, Cherry Valley,” 24 August 1887. Cherry Valley, a hamlet a few miles southeast of Rockford, is now part of the larger town’s metropolitan area. Courtesy of the Oriental Institute, University of Chicago.

Curtiss began teaching at the Chicago Theological Seminary in 1878. He introduced Old Testament literature and Hebrew into the seminary’s curriculum, thus leading a handful of scholars working to transform American seminary education. At his formal installation in 1879 he pleaded “for a more thorough study of Semitic Languages,” by 1882 he created a “prize division” in Hebrew to encourage students to master it, and he offered a correspondence course in Hebrew for prospective students. Curtiss taught “Hebrew as one would teach a modern language, where the effort should be not only to read but also speak the language,” and he claimed to have been “one of the first, if not the first, to introduce the custom of sight reading.” Under Curtiss’s leadership, rigorous Hebrew training enabling students to study the Old...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Copyright

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Maps

- Epigraph

- Note to the Reader

- 1 Equipment for a Great Work

- 2 What the Monuments Say

- 3 Two Years, Three Books, Seven Volumes

- 4 Expeditions to Nubia

- 5 Spreading Wings

- 6 The Near East as a Whole

- 7 An Institute, a Calling

- 8 Permanence

- 9 A Historical Laboratory

- Epitaph

- Acknowledgments

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index