- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The HIV/AIDS epidemic in Africa has defined the childhoods of an entire generation. Over the past twenty years, international NGOs and charities have devoted immense attention to the millions of African children orphaned by the disease. But in Crying for Our Elders, anthropologist Kristen E. Cheney argues that these humanitarian groups have misread the 'orphan crisis'. She explains how the global humanitarian focus on orphanhood often elides the social and political circumstances that actually present the greatest adversity to vulnerable children—in effect deepening the crisis and thereby affecting children's lives as irrevocably as HIV/AIDS itself.

Through ethnographic fieldwork and collaborative research with children in Uganda, Cheney traces how the "best interest" principle that governs children's' rights can stigmatize orphans and leave children in the post-antiretroviral era even more vulnerable to exploitation. She details the dramatic effects this has on traditional family support and child protection and stresses child empowerment over pity. Crying for Our Elders advances current discussions on humanitarianism, children's studies, orphanhood, and kinship. By exploring the unique experience of AIDS orphanhood through the eyes of children, caregivers, and policymakers, Cheney shows that despite the extreme challenges of growing up in the era of HIV/AIDS, the post-ARV generation still holds out hope for the future.

Through ethnographic fieldwork and collaborative research with children in Uganda, Cheney traces how the "best interest" principle that governs children's' rights can stigmatize orphans and leave children in the post-antiretroviral era even more vulnerable to exploitation. She details the dramatic effects this has on traditional family support and child protection and stresses child empowerment over pity. Crying for Our Elders advances current discussions on humanitarianism, children's studies, orphanhood, and kinship. By exploring the unique experience of AIDS orphanhood through the eyes of children, caregivers, and policymakers, Cheney shows that despite the extreme challenges of growing up in the era of HIV/AIDS, the post-ARV generation still holds out hope for the future.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Crying for Our Elders by Kristen E. Cheney in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & AIDS & HIV. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University of Chicago PressYear

2017Print ISBN

9780226437545, 9780226437408eBook ISBN

9780226437682Part One

Generations of HIV/AIDS, Orphanhood, and Intervention

1

A Generation of HIV/AIDS in Uganda

In her edited volume Second Chances: Surviving AIDS in Uganda, Susan R. Whyte and her colleagues describe the outcomes of a longitudinal study on the progression of the AIDS epidemic in Uganda through the concept of a “biogeneration,” a cohort of people whose life experiences are “defined by the management of an epidemic and an innovative package of care” (Whyte 2014, 2). Whyte goes on to describe the history of public health interventions that accompanied the spread of HIV/AIDS and eventually turned the tide of the disease—not only through prevention but through the introduction of treatment, particularly antiretroviral therapy (ART). ART transformed the diagnosis of HIV from an automatic death sentence to a manageable disease. As Whyte notes, Uganda is a good country in which to follow AIDS’s first generation of survivors (2014, 4) because Uganda was one of the countries first and hardest hit by the epidemic. The Ugandan government was also the first to respond in a concerted, multisectoral way. Whyte observes that “the first generation to benefit from ART in Uganda had been more exposed than citizens of other eastern and southern African states to massive information campaigns and a multitude of AIDS projects well before effective treatment rolled out” (2014, 4).

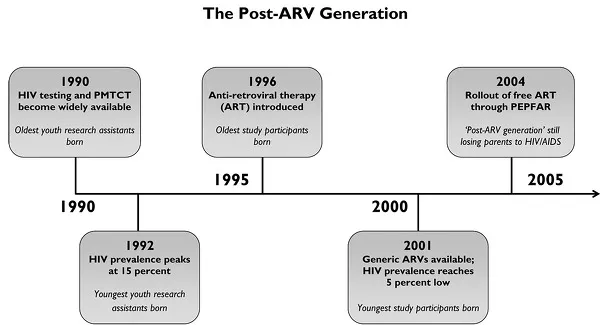

These campaigns helped bring about declines in both the prevalence and the incidence of HIV infections. The advent of ART has thus also punctuated the lives of the children with whom I have worked since 2000. HIV testing became available in Uganda in 1990, the time around which the children whose life histories I chronicled in Pillars of the Nation (Cheney 2007b) and who served as youth research assistants for this project were born. The prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) of HIV treatment became widely available in 2000, the year in which I began fieldwork for Pillars. ART was introduced in Uganda in 1996, but it was far too expensive for everyone but the very wealthy. When generics came on the market in 2001, however, the possibility of long-term survival through the medical management of HIV became available to a greater number of Ugandans. And when the US President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) made Uganda one of its top three aid recipients in 2004, many thousands more started receiving free ART (Whyte 2014, 5–7). The availability of treatment affected the cohort of children with whom we did youth participatory research for this volume, who were born between 1996 and 2002 (see time line in fig. 1). We might well call this generation the “post-ARV generation,” then.

Figure 1. Time line of the post-ARV generation.

The biogeneration on which Whyte and her colleagues focused were people around thirty to forty years old at the time of research in the early part of the first decade of the twenty-first century. While “the notion of generation invites us to inquire into the distinctive consciousness that characterizes those who experience fateful historical events” (Whyte 2014, 13), the consciousness of children is often overlooked or discounted. Whyte and her associates opted to concentrate on those who had reached adulthood by the time treatment—what they identify as the defining moment of the era—was made widely available in the first few years of the twenty-first century. Yet HIV/AIDS may actually have had the greatest impact on the children who were born and came of age in the wake of the development of such treatments. While the young children we talked to during intensive fieldwork from 2007 to 2009 may not have had a “generational consciousness” related to the spread and treatment of AIDS at the time (most were five to ten years old), it has clearly had an impact on their lives, especially those for whose parents’ ARV treatment became accessible too late to prolong their lives. This book is thus dedicated to understanding how children of the post-ARV generation, particularly orphaned children, were affected by and experienced the same post-ART era of the HIV/AIDS pandemic described by Whyte et al. I start first with an overview of the broader national and international developments in HIV/AIDS treatment—as they relate to orphans—to set the stage for the latter parts of the book, which deal with the more local and household-level social contexts of orphans’ lives.

The Course of the HIV/AIDS Epidemic in Uganda

Numerous sources have detailed how Uganda, being at the epicenter of the African AIDS pandemic, showed relatively early government leadership in seeking international assistance to identify and combat the disease (Thornton 2008; Seeley 2014). Government’s attention was initially on prevention, as no cure or treatment was known; it launched major public education campaigns and managed to help Uganda become one of two countries (the other being Senegal, whose AIDS epidemic never reached the same proportions) to reverse its HIV prevalence rate from a peak of about 15 percent (and 30 percent among pregnant women tested in prenatal clinics) in 1992 to a low of about 5 percent in 2001. Some countries still have not embraced leadership in AIDS prevention, and that decision has had far more disastrous consequences for them.

Scholars have variously theorized the reasons for Uganda’s apparent success versus the failures of other nations to tackle the rise in HIV/AIDS infections in the 1980s and 1990s. In her book The Invisible Cure: Why We Are Losing the Fight against AIDS in Africa (2007), Helen Epstein posits that Ugandans’ early success in battling AIDS was due to their acceptance of the vector of transmission and subsequent behavior change amid concurrent sexual relationships—overlapping long-term relationships—that typically occur in African communities. Robert Thornton’s sexual network theory similarly posits that AIDS circulated in comparatively tight sexual networks in Uganda, where understandings of AIDS were indigenized early in the epidemic (Thornton 2008). Unlike Epstein, however, Thornton believes that rather than attributing the reduction in AIDS infections solely to individual behavior change, much more cultural and social shifts in sexual networks are also responsible. Janet Seeley’s historical overview, HIV and East Africa: Thirty Years in the Shadow of an Epidemic, argues that “sexual activity occurs in the context of a person’s life course. But this broader context is often overlooked in the urge to identify individuals in particular ‘risk groups’” (2014, 4). Seeley therefore sets to the task of contextualizing the spread of HIV and AIDS in relation to social, historical, and economic events in the region’s recent history, noting variations and fluctuations across time and space.

One aspect that is generally agreed on is that Uganda was unique in its early recognition of—and intervention in—AIDS as an urgent matter of public health. This quick response accordingly yielded early successes, especially with PMTCT drastically reducing the national rate of transmission to children during pregnancy. Less discussed, however, is the adverse effect this treatment has had on children who survive and are orphaned as their mothers and fathers succumb to AIDS. As the orphan population in Africa exploded in the 1990s, extended families that are traditionally responsible for orphan care were trying to meet the needs of their families as people died before raising their children. International and government interventions thus centered on strengthening existing social safety nets and bolstering their resilience. Uganda tackled the disease itself first, but the response to the fact of children becoming orphaned came later. AIDS, in other words, was treated first and foremost as a medical phenomenon, to the detriment of attention toward its devastating social effects, such as mass orphanhood.

In the late 1990s and the early twenty-first century, UNICEF (the United Nations Children’s Fund, originally the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund) increased efforts to highlight the plight of children affected by AIDS by adopting a purposefully broad definition of an orphan as any “child under 18 years of age whose mother, father, or both parents have died” (UNICEF 2006, 4). By this definition, UNICEF could claim that an estimated 53 million sub-Saharan African children had been orphaned by 2006—30 percent (15.7 million) of them by AIDS (UNICEF 2006, iv). In turn, many international nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and charities have focused on the plight of AIDS orphans—then children affected by AIDS (CABA), orphans and vulnerable children (OVC), and so on (see chapter 2 for a brief etymology of orphan terminology). But this humanitarianism often comes with adverse consequences, intended or unintended.

The way UNICEF’s definition inflated orphan numbers led to an outcry about an imminent “orphan crisis” that threatened to overwhelm extended-family systems and leave thousands of children without care. Following UNICEF, scholars and practitioners began to use the term orphan crisis both widely and uncritically (Guest 2003; Roby and Shaw 2006; Drah 2012). Yet UNICEF’s broad definition can distort local definitions by singling out orphaned children as particularly vulnerable despite widespread extended-family social safety nets (Meintjes and Giese 2006; Sherr et al. 2008). Nonetheless, international responses in the 1980s and 1990s tended to focus on the “orphan” in isolation from the extended family, and even from the broader community. While this portrayal elicits a variety of charitable, humanitarian responses out of sympathy for parentless children, inflating orphan numbers to attract scarce resources ultimately does little to remedy the structural issues that lead to orphanhood in the first place (Cheney 2010). I return to this point in chapter 2.

The trajectory of the African AIDS pandemic is still playing out as the number of orphans requiring care continues to increase. There are several reasons for this. First, there is a lag between peak HIV prevalence (the proportion of cases relative to the total population) and death due to AIDS, which means the number of orphans increases even after HIV prevalence drops—but HIV prevalence in fact rose again in Uganda from 6.4 percent in 2005 to 7.3 percent in 2011, and the incidence, or probability of occurrence, also rose slightly until 2012, when it began to decline again (Uganda AIDS Commission 2014, vii). Though Uganda has seen a dramatic drop in the number of children newly infected with HIV as a result of PMTCT rollout, new infection rates remain high among the adult population (Uganda AIDS Commission 2014), which means that the probability that Ugandan children will continue to be orphaned by AIDS also remains high.

Second, the coverage of antiretroviral therapy has still not been sufficient to prevent the deaths of all parents. According to the World Bank, only 38 percent of all Ugandans who needed ART were in fact receiving it in 2013.1

Third, the ART coverage for children is even lower: in 2011, only 21 percent of the HIV-positive Ugandan children ranging in age from infancy through age fourteen were receiving ART in 2011 (UNICEF 2012). Though coverage remains insufficient,2 more HIV-positive children receiving ART also means that those children, who would otherwise likely have died by age five (Sikstrom 2014, 47), are now living to adulthood—but often as orphans. Such survival occurs because most were infected perinatally, so their parents may since have died while the children have survived (a situation true of all four HIV-positive children in the present study). Even as adult mortality drastically fell following the rollout of ART, HIV-positive children’s survival inflates orphan numbers.

In other words, only recently have efforts turned attention toward orphans as an unfortunate outcome of the epidemic, and only recently have ARVs been made more widely available to people with HIV, which has helped prolong their lives long enough for them to raise their children. But ARVs have come too late to stem the proliferation of orphans in the early twenty-first century. In the meantime, extended families and communities who were caring for nonbiological children were disproportionately strained, leading to increased overall poverty.

Community-based organizations (CBOs) and NGOs were the first organized responders to the proliferation of AIDS orphans. Many CBOs started with small interventions for the children they saw suffering in their own communities, particularly when they saw that children were heading households themselves or taking to the streets due to lack of parental care. Despite small-scale community efforts to attend to orphan needs, however, orphans and vulnerable children remained largely invisible in early HIV/AIDS care, prevention, and treatment programs. Government response to the orphan crisis was delayed, perhaps relying on extended family networks to continue absorbing orphans until it became clear that these traditional means of orphan support were being stretched beyond their capacity by the AIDS pandemic.

Despite pressure from below, the development of national OVC policies was largely the result of consultation with international donors and NGOs. The Rapid Assessment, Analysis, and Action Planning (RAAAP) initiative—established by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), UNICEF, the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), and the World Food Programme—coordinated the efforts of seventeen sub-Saharan African countries’ strategic planning to meet the needs of the growing numbers of orphans in their countries in 2003 (POLICY Project 2005). Although these countries developed national plans of action, only six African countries had developed national policies for orphan care by the end of 2003 (Roby and Shaw 2006, 201). Uganda did not implement its policy until 2004—twelve years after peak HIV prevalence. Though national OVC policies thus happened to some extent by default, their establishment still holds promise for the 17.7 million children worldwide who have been orphaned by AIDS—10.5 million of them in Eastern and Southern Africa, and 1.1 million in Uganda alone (UNAIDS 2013; UNICEF 2014)—that their governments and civil society are taking leadership on the issue, as any policy that focuses on child well-being is better late than never.

Enter PEPFAR

Uganda’s rollout of its OVC policy was also the year that US President George W. Bush’s administration rolled out the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR). PEPFAR was established in 2004 with a $15 billion budget to treat and prevent HIV and AIDS in Africa. Uganda was one of the target countries and one of the top three recipients of funding (Whyte 2014, 7). Despite the incredible investment PEPFAR made in public health in Africa, however, it was not without its politics.

At an African Studies Association meeting I attended during the course of this study, I met one of the scholars who had been hired by the US government to research and compile a report on which it would base the initial PEPFAR budget allocation.3 He told me how his team was first sent to Uganda for several months of fact-finding about the effective measures Ugandans had taken to reduce their HIV infection rate—after which they would move on to conduct similar research in six other sub-Saharan African countries. The team went north, south, east, and west in the country talking to patients, doctors, policy makers, and others, gathering data on Uganda’s HIV “success story.” After the initial gathering of data, some PEPFAR representatives from Washington, DC, flew in to Kampala to receive a progress report from the research team. As the team ran through its presentation in a conference room at the Sheraton Hotel, they listed some of the treatment and prevention methods that had been shown to be most successful in Uganda, including the prevention of mother-to-child transmission, the creation of AIDS support groups, voluntary counseling and testing (VCT), condom use—“Stop!” interrupted a PEPFAR representative with a raised, open palm. “You’re not going to talk about condoms.” The team was shocked and baffled by this interruption; the team members rebutted that they had gathered definitive evidence that condoms, when used correctly, were a substantial factor in the reduction of HIV prevalence in Uganda. But the Washington representatives insisted that they were not going to entertain any suggestions about condom use when it came to prevention. They were adamant that PEPFAR prevention programs would emphasize abstinence approaches, evidence or no evidence. Some team members tried to negotiate while others broke down in tears of frustration that scientific inquiry was apparently once again being hijacked for political purposes.

The research team continued to plead, but the representatives finally said that if the research team insisted on talking about condom use, they would cancel the rest of the seven-country fact-finding mission. The team insisted on the integrity of the members’ own reputations as researchers, so the rest of the research mission was canceled. Some researchers threw their hands up, walked out, and went straight to the airport while others sat stunned for a time. The team member told me that the representatives returned to Washington, DC, and commissioned a member of the Presidential Advisory Council on HIV/AIDS to write the report without taking any of their research into account.

PEPFAR has been touted in popular media as an altruistic and overwhelming success (in 2008, the US Congress reauthorized the program to the tune of $48 billion), but many observers have since written critiques of PEPFAR’s latent politics (Susser 2009; Thornton 2008). While PEPFAR has received accolades for extending the lives of millions of people on PEPFAR-funded ARV treatments (including several children in this study), it has done so by supporting a mosaic of projects, from secular and faith-based NGOs to state and regional efforts. Whyte points out that not only was these programs’ sustainability dependent on the continuance of foreign funding but that “PEPFAR . . . did not exclusively or even primarily target the public health system. In some ways, the NGO and international donor AIDS projects undermined the government health care system by drawing health workers away to better-pa...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Abbreviations

- Introduction

- PART 1 Generations of HIV/AIDS, Orphanhood, and Intervention

- PART 2 Beyond Checking the “Voice” Box: Children’s Rights and Participation in Development and Research

- PART 3 Orphanhood in the Age of HIV and AIDS

- PART 4 Blood Binds: The Transformation of Kinship and the Politics of Adoption

- PART 5 Conclusion

- Acknowledgments

- Appendix: Children and Household Profiles by Youth Research Assistant Focus Group, 2007–2009

- Notes

- References

- Index