- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Piechocki calls for an examination of the idea of Europe as a geographical concept, tracing its development in the 15th and 16th centuries.

What is "Europe," and when did it come to be? In the Renaissance, the term "Europe" circulated widely. But as Katharina N. Piechocki argues in this compelling book, the continent itself was only in the making in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.

Cartographic Humanism sheds new light on how humanists negotiated and defined Europe's boundaries at a momentous shift in the continent's formation: when a new imagining of Europe was driven by the rise of cartography. As Piechocki shows, this tool of geography, philosophy, and philology was used not only to represent but, more importantly, also to shape and promote an image of Europe quite unparalleled in previous centuries. Engaging with poets, historians, and mapmakers, Piechocki resists an easy categorization of the continent, scrutinizing Europe as an unexamined category that demands a much more careful and nuanced investigation than scholars of early modernity have hitherto undertaken. Unprecedented in its geographic scope, Cartographic Humanism is the first book to chart new itineraries across Europe as it brings France, Germany, Italy, Poland, and Portugal into a lively, interdisciplinary dialogue.

What is "Europe," and when did it come to be? In the Renaissance, the term "Europe" circulated widely. But as Katharina N. Piechocki argues in this compelling book, the continent itself was only in the making in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.

Cartographic Humanism sheds new light on how humanists negotiated and defined Europe's boundaries at a momentous shift in the continent's formation: when a new imagining of Europe was driven by the rise of cartography. As Piechocki shows, this tool of geography, philosophy, and philology was used not only to represent but, more importantly, also to shape and promote an image of Europe quite unparalleled in previous centuries. Engaging with poets, historians, and mapmakers, Piechocki resists an easy categorization of the continent, scrutinizing Europe as an unexamined category that demands a much more careful and nuanced investigation than scholars of early modernity have hitherto undertaken. Unprecedented in its geographic scope, Cartographic Humanism is the first book to chart new itineraries across Europe as it brings France, Germany, Italy, Poland, and Portugal into a lively, interdisciplinary dialogue.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Cartographic Humanism by Katharina N. Piechocki in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & European History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University of Chicago PressYear

2021Print ISBN

9780226816814, 9780226641188eBook ISBN

9780226641218CHAPTER ONE

Gridding Europe’s Navel: Conrad Celtis’s Quatuor Libri Amorum secundum Quatuor Latera Germanie (1502)

In 1493, Conrad Celtis (1459–1508), the first poet laureate of the Holy Roman Empire, signed a contract with the influential Nuremberg politician and merchant Sebald Schreyer, who that year had just sponsored the publication of Hartmann Schedel’s hexameral Liber Chronicarum, widely known as the Nuremberg Chronicle,1 a lavishly illustrated work described as “the most complex printing project before 1500.”2 With the immense success of the Chronicle in mind, Schreyer was eager to invest in a second edition of the volume, the contract for which specified the addition of a hitherto unprecedented emphasis: a “New Europe” (Newen Europa).3 The choice of “the poet Conrad Celtis” to “correct anew” and “recast in a different form”4 the Chronicle is hardly surprising: Celtis would rise to become the German lands’ first and foremost cartographic writer, whose poetic work displays profound knowledge of Ptolemy’s Geography and a keen interest in the cartography of his time. He was the first early modern humanist to introduce the word “topography” as a critique of the traditional Ptolemaic dichotomy between chorography and cosmography, which he found insufficient to reflect Europe’s rapidly changing contours.

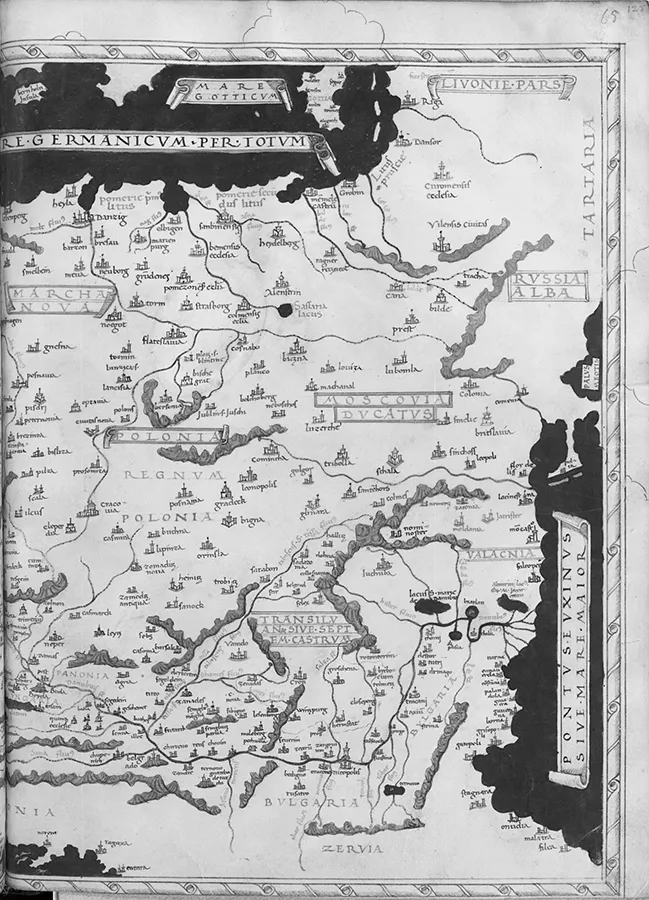

Celtis’s project of revising Schedel’s Chronicle marks the beginning of a momentous shift in the making of Europe. If the tradition of hexameral writing is often seen as offering “poignant responses to a crisis of world order,”5 Celtis’s own work grapples with the delineation of a smaller, newly emerging entity: the continent of Europe. In the end, Celtis did not uphold his end of the contract with Schedel and no second edition of the Chronicle was ever published. Yet Celtis’s interest in defining a “new Europe,” a project executed by Sebastian Münster in 1544, took shape in another large-scale project: the Germania illustrata,6 with an eye to Flavio Biondo’s Italia illustrata, whose core—four books of love elegies, a description of Nuremberg (Norimberga), and a treatise on Germany (Germania generalis), among others—appeared in Nuremberg under the title Quatuor Libri Amorum secundum Quatuor Latera Germanie in 1502.7 Prefaced by a woodcut by a young Albrecht Dürer and accompanied by fanciful regional maps of Germany by different artists, it is Germany’s most original example of early modern cartographic humanism. The Quatuor Libri Amorum, at the center of this chapter, is a unique realization of Celtis’s desire both to capture poetically and cartographically the outlines of a “New Europe” in a dramatically changing world and to strengthen Germany’s position within it. As he avoids facile explanatory models, Celtis proposes the question of defining Europe, in all its breadth and complexity.

Translatio Cartographiae

The Quatuor Libri Amorum, written in neo-Latin hexameters, has been defined as a work of “erotic topography.”8 Celtis himself referred to the four books of poems as “lasciva quaedam nostra carmina” (“those lascivious songs of mine”).9 In the Latin elegiac tradition of Ovid, Propertius, and Tibullus, the four books of elegies proper—the core of the Quatuor Libri Amorum—follow the story of a lovesick protagonist, a secular pilgrim in search of erotic encounters, from his youth to his old age, along Germany’s borders, represented by the four cities of Kraków, Regensburg, Mainz, and Lübeck. With an eye to both Francesco Petrarca’s Canzoniere (revised until the poet’s death in 1374) and Matteo Boiardo’s Amorum libri tres (composed between 1469 and 1476), the Quatuor Libri Amorum is a groundbreaking attempt to embed love poetry within a cartographic framework. As scholars have pointed out, the genre of the poema elegiacum was “integrative”;10 it allowed the elegiac poet to experiment across disciplines. Yet Celtis’s Quatuor Libri Amorum is unique in its imaginative formulation of a tight nexus between poetry and cartography, combined and redirected here in a hitherto unprecedented manner: to design the contours of Europe.

The Quatuor Libri Amorum opens with a powerful iconographic statement: a woodcut by Albrecht Dürer, probably Celtis’s most famous mentee, on one of the volume’s first pages (fig. 2). Commissioned specifically for Celtis’s volume, the woodcut is one of Dürer’s earliest artworks. Here, Philosophy is represented as an allegorized female figure, whose heart coincides with the tip of a pyramid-shaped scala artium, at the base of which appear Dürer’s initials. Inscribed in the pyramid are the seven liberal arts: grammar, logic, rhetoric, arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, and music. Two mottos, located at the top and the bottom of the woodcut, reproduce Philosophy’s words and trace the movement of translatio studii from antiquity (with an allusion to Afranius’s racy comedies) to the present (Celtis’s own Germany): “Sophiam me Greci vocant Latini Sapientiam / Egipcii & Chaldei me invenere Greci scripsere / Latini transtulere Germani ampliavere” (The Greeks call me “Sophia,” the Latins “Sapientia,” / The Egyptians and Chaldeans invented me, the Greeks wrote me down, / The Latins translated me, the Germans amplified me).11 Arranged into three lines, this motto denotes the trivium, while the motto on the bottom of the woodcut, composed in four lines, is a nod to the four elements and the quadrivium: “Quicquid habet Coelum quid Terra quid Aer & aequor / Quicquid in humanis Rebus & esse potest / Et deus in toto quicquid facit igneus orbe / Philosophia meo pectore cuncta gero” (Whatever holds the Sky, whatever the Earth, whatever the Air and the sea / Whatever in human Things there is and can be / And whatever the Fire god makes in the whole world / I, Philosophy, bear all in my breast).12 Raymond Klibansky, Erwin Panofsky, and Fritz Saxl remark that in this woodcut Dürer’s figure is deeply rooted in the “medieval tradition”13 of allegorical representations of “Lady Philosophy” and contend that the allegory, lacking novelty, simply perpetuates a millennial tradition of depicting Philosophy as a female allegory, initiated by Boethius: Renaissance humanism, these scholars seem to suggest, had not yet penetrated north of the Alps. Celtis scholars have largely followed suit.14

But a more careful examination reveals that in the first medallion atop the garland Dürer inserts none other than Ptolemy holding an armillary sphere, suggesting that “Philosophia” and the translatio studii originate with the second-century-CE Roman geographer from Alexandria. Plato, who stands for the “Grecorum Philosophi” (Greek Philosophers), and Cicero and Virgil, representatives of the “Latinorum Poetae et Rhetores” (Latin Poets and Rhetoricians), are all anachronistically displaced: despite having preceded him in time, they appear on Dürer’s woodcut as followers of Ptolemy. In the last medallion, Albertus Magnus, the medieval German natural philosopher and cartographic thinker,15 stands to represent the “Germanorum Sapientes” (German Philosophers). It is with Albertus Magnus that the movement of translatio—an itinerary leading from Ptolemy’s Egypt to Greece, Rome, and finally Germany—comes to a close. The chronological framework is here disrupted and supplanted by spatial reasoning. In its embrace of the translatio studii and the seven liberal arts, Philosophy is here cast under the aegis of geography and cartography as a new epistemic tool and unique key to Celtis’s work. The woodcut emerges as what may indeed be termed a translatio cartographiae, a critical reflection on the rise of cartography and its impact on the organization of knowledge and learning from Ptolemy’s Alexandria to Celtis and Dürer’s own Germany. In an epochal shift, cartography becomes a strategic intervention, a critical enabler of philosophy and poetry alike, allowing Albertus (the author of, among other books, De natura locorum, a widely acclaimed geographic treastise)16 to complete the arc of translatio cartographiae by vigorously redirecting cartographic thought to the German lands.17

A catalyst for cartographic writing, Philosophy in Dürer’s woodcut becomes something new, a dynamic interplay of poetics and visual arts under the overarching umbrella of a newly emerging discipline. As he combines text and image throughout Quatuor Libri Amorum (by including creative woodcut illustrations and imaginative regional maps of Germany in all four books of elegies), Celtis strengthens Germany’s position as a producer of cartographic humanism. Celtis powerfully invigorates the tradition of cartographic writing,18 even with regard to Italy, whose printed geographies were commonly more “iconophobic”: from Biondo’s Italia illustrata to Leandro Alberti’s 1550 Descrittione di tutta Italia, cartographic Italian works were consistently published without maps even, as Theodore Cachey observes, “at a time when printed maps were in wide circulation and quite common in geographical literature, isolarii, and atlases.”19 By casting Philosophy within a framework that binds the cartographic word and image to one another, Celtis and Dürer effect an unparalleled change in perspective and positionality—from Italy to the German lands.

Nuremberg: Gridding the Navel of Europe

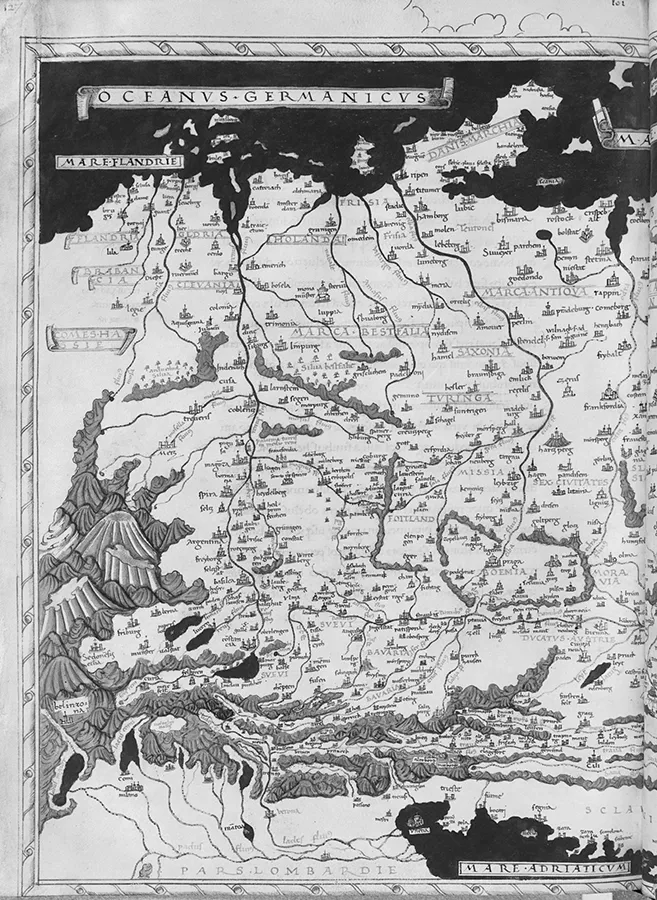

Celtis’s cartographic desire to conceive of a “New Europe” was perhaps propelled by Schedel’s strategic decision to position at the exact center of his Chronicle a visual and narrative description of Nuremberg, which, by around 1500, had reached the peak of its wealth, eminence, and cultural and scientific achievement. It was considered the “secret capital” of the Holy Roman Empire, where the imperial regalia, the so-called “Nürnberger Kleinodien,”20 were kept from 1424 to 1796. It was also the epicenter of the production of maps and globes and of artistic, cartographic, astronomical, and mathematical innovation. Around 1493, Georg Stuchs printed here the so-called “German Ptolemy,”21 a treatise containing thirty-five sheets and the first map using a globular projection; here, Martin Beheim and Johann Schöner created the first extant terrestrial globes in 1492 and 1515, respectively;22 the century’s most revolutionary and courageous book, Nicolaus Copernicus’s De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres), was originally printed in Nuremberg in 1543 by Hans Peterlein (Johannes Petreius). Nuremburg was host to many artists and scientists: Nicolaus Cusanus, commonly considered to be the first creator of a map of Central Europe (fig. 3); Willibald Pirckheimer, author of Germaniae ex variis scriptoribus perbrevis explicatio (Short Exposition of Germany based on Various Writers) and translator of Ptolemy’s Geography; Hieronymus Münzer, who designed, among many other things, the first printed map of Germany for Schedel’s Chronicle; and, last but not least, Germany’s most famous Renaissance artist, Albrecht Dürer.

Figure 3. “Insularium illustratum” (Cusanus map), Central Europe by Henricus Martellus (Northern Italy, ca. 1480) [Ms698-folio65recto and Ms698-folio65verso]. Photograph: © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, New York.

This pivotal city adopted a dual mission: to attract scholars, artists, and humanists from different parts of Europe and to serve as a point of departure to explore and measure the boundaries of Germany, Europe, and the world. Nuremberg’s self-promotion as the center of the Holy Roman Empire dovetailed with the interest expressed in the city for territorial exploration and overseas expansion. Its artists, scientists, and merchants either were eager travelers themselves or were interested in the concomitant “discoveries” unfolding across the globe. Globe maker Martin Behaim, for instance, was a student of the astronomer Johann Müller (Regiomontanus) in Nuremberg and a merchant who worked for the Portuguese crown. Having probably taken part in the second voyage of Diogo Cão (1485–86) along Africa’s western coast,23 Behaim commissioned, upon his ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- contents

- List of Figures

- On Translations

- Introduction

- 1. Gridding Europe’s Navel: Conrad Celtis’s Quatuor Libri Amorum secundum Quatuor Latera Germanie (1502)

- 2. A Border Studies Manifesto: Maciej Miechowita’s Tractatus de duabus Sarmatiis (1517)

- 3. The Alpha and the Alif: Continental Ambivalence in Geoffroy Tory’s Champ fleury (1529)

- 4. Syphilitic Borders and Continents in Flux: Girolamo Fracastoro’s Syphilis sive Morbus Gallicus (1530)

- 5. Cartographic Curses: Europe and the Ptolemaic Poetics of Os Lusíadas (1572)

- Conclusion

- Acknowledgments

- Notes

- Index