eBook - ePub

Visions of Sodom

Religion, Homoerotic Desire, and the End of the World in England, c. 1550-1850

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Visions of Sodom

Religion, Homoerotic Desire, and the End of the World in England, c. 1550-1850

About this book

The book of Genesis records the fiery fate of Sodom and Gomorrah—a storm of fire and brimstone was sent from heaven and, for the wickedness of the people, God destroyed the cities "and all the plains, and all the inhabitants of the cities, and that which grew upon the ground." According to many Protestant theologians and commentators, one of the Sodomites' many crimes was homoerotic excess.

In Visions of Sodom, H. G. Cocks examines the many different ways in which the story of Sodom's destruction provided a template for understanding homoerotic desire and behaviour in Britain between the Reformation and the nineteenth century. Sodom was not only a marker of sexual sins, but also the epitome of false—usually Catholic—religion, an exemplar of the iniquitous city, a foreshadowing of the world's fiery end, an epitome of divine and earthly punishment, and an actual place that could be searched for and discovered. Visions of Sodom investigates each of these ways of reading Sodom's annihilation in the three hundred years after the Reformation. The centrality of scripture to Protestant faith meant that Sodom's demise provided a powerful origin myth of homoerotic desire and sexual excess, one that persisted across centuries, and retains an apocalyptic echo in the religious fundamentalism of our own time.

In Visions of Sodom, H. G. Cocks examines the many different ways in which the story of Sodom's destruction provided a template for understanding homoerotic desire and behaviour in Britain between the Reformation and the nineteenth century. Sodom was not only a marker of sexual sins, but also the epitome of false—usually Catholic—religion, an exemplar of the iniquitous city, a foreshadowing of the world's fiery end, an epitome of divine and earthly punishment, and an actual place that could be searched for and discovered. Visions of Sodom investigates each of these ways of reading Sodom's annihilation in the three hundred years after the Reformation. The centrality of scripture to Protestant faith meant that Sodom's demise provided a powerful origin myth of homoerotic desire and sexual excess, one that persisted across centuries, and retains an apocalyptic echo in the religious fundamentalism of our own time.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Visions of Sodom by H. G. Cocks in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

The Roman Sodom

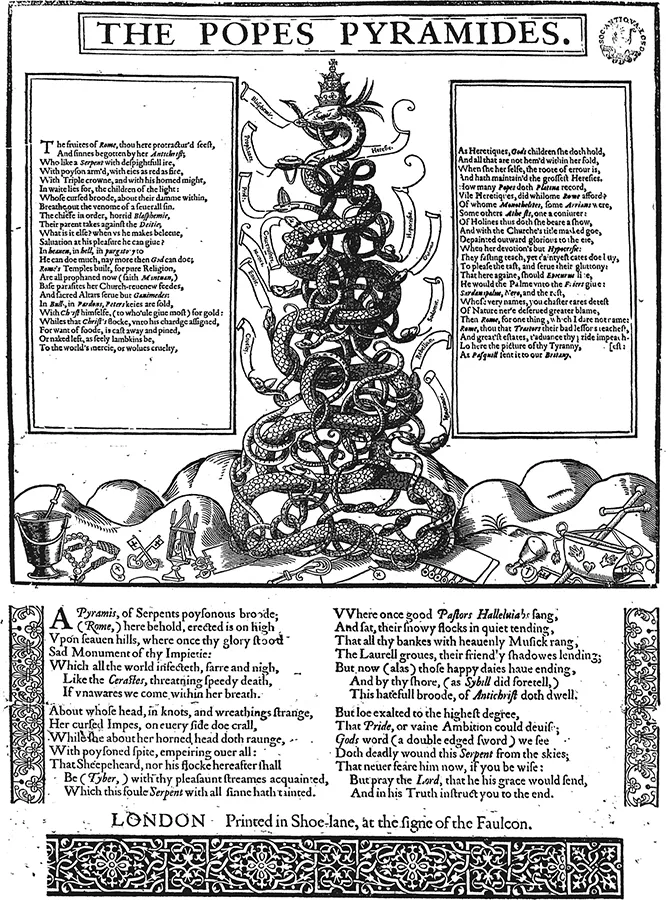

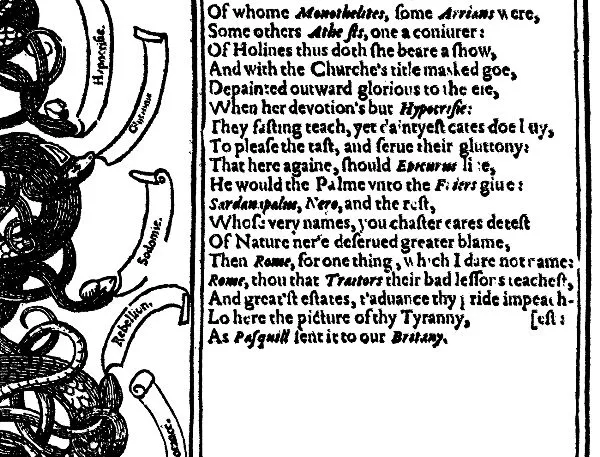

“I plaine proclaime and prove by prophecie,” wrote the mathematician and millenarian theorist John Napier in 1593 in his Plaine Discovery of the Whole Revelation of St John, that “Rome, raised up on hills seven, Citie supreme and seat of Sodomie,” was that same earthly city destined—according to Saint John’s Apocalypse—to burn at the end of time. For Napier, Saint John had prophesied the corruption of the Roman Church, and the proof of that vision lay in the fact that, of the popes, thirteen had been adulterers, three “common brothellers,” four “incestuous harlots,” while at a conservative estimate no fewer than eleven “were impoisoned with vile Sodomie.”1 In 1624 the anonymous author of a handbill showing The Pope’s Pyramides repeated the charge, depicting the “fruites of Rome and Sinnes begotten by her Antichrist” as a series of writhing, interlocking serpents: blasphemy, profaneness, pride, covetousness, envy, cruelty, heresy, hypocrisy, rebellion, and sodomy (figs. 2 and 3). Even those notorious immoralists of the ancient world, Nero and Sardanapaulus, did not deserve greater blame, its author said, “then Rome, for one thing, which I dare not name.”2

Figure 3. The Pope’s Pyramides (1624). By kind permission of the Society of Antiquaries of London. Image published with permission of ProQuest. Further reproduction is prohibited without permission. Image produced by ProQuest as part of Early English Books Online. www.proquest.com

Figure 4. The Popes Pyramides (detail)

Why was Catholic Rome the author of sodomy? Because it had been prophesied in scripture. The anonymous balladeer and the learned academic were united in that assumption. For many Protestants, this language was a vital part both of affirming that their religion represented the true church and of identifying the papacy with Antichrist. The sexual invective that resulted from this prophetic logic was used to prove the point. Like the broader antipopery that was its parent ideology, the idea of Rome as the source of sodomy performed three overlapping functions for Protestant writers. First, as Napier’s poem suggests, it helped to align earthly events and apocalyptic prophecies. Specifically, this language helped to distinguish the true church from the false and thereby to draw Catholicism in the starkest and most vivid colors. The depiction of the “sodometry” that resulted from banning clerical marriage and a more general Catholic moral relativism helped to knit together history and prophecy, the apocalypse and worldly events.

For many seventeenth-century writers, locating sodomy in Rome helped to explain the pattern of history as a series of confrontations with Antichrist, the final battle against whom prefigured either the millennium or the Last Days. Second, sodomy was one of the characteristics of Antichrist and could therefore be used to identify him and his seat. Finally, the attack on sodomy functioned like antipopery more generally. After 1660 it was used even by theological moderates and mainstream churchmen to connect a reformed tradition that dated back to the original break with Rome, one that aimed at cementing the unity of Protestants by drawing a clear line between themselves and their Catholic antagonists. Although the language of popery could be directed against the “remnants” of popish ceremony in the English Church or toward those sects thought to be undermining true religion through schism, the idea that sodomy was the particular responsibility of Rome remained largely inviolate in religious polemic. Although Protestant sects might be accused of holding women in common, or of a generalized fornication, the rhetoric of sodomy was rarely if ever directed against one’s coreligionists. As a result, this language could be deployed in an effort to secure broad opposition to obvious and glaring evils. For all the changing nature of antipopery across the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the idea that sodomy was a property of the papal Antichrist and his jurisdiction functioned not only as motif of apocalyptic history but also as an appeal to the evanescent goal of Protestant unity.

Although the idea of the Church as mired in corruption, sexual and otherwise, predates the Reformation, after the rise of Protestantism its adherents attacked Roman Catholicism for its supposed tendency toward fornication, unnatural desires, and forbidden sexual acts with renewed vigor. While this was noticed by most historians of the Reformation, for a long time they sought to play it down. The great ecclesiastical historian John Strype, for instance, was not alone in singling out the “bilious” Henrician polemicist and historian John Bale—one of the most outspoken critics of Roman sodomy—for attention. He, Strype noted in 1721, “is sometimes blamed, and blameworthy indeed, for his rude and plain language,” and in 1846 S. R. Maitland decided that Bale’s pen was foul “simply because he was foul himself.” His “scurrilous railing and ribaldry,” Maitland concluded, was not only “obscene” but symbolized a persistent trend within radical Protestantism that had actually encouraged the Marian persecutions. Bale, he wrote, was “full of that fierce, truculent, and abusive language, and that loathsome ribaldry, which characterized the style of too many of the puritan writers.”3

More recently though, Helen Parish, Peter Lake, and others have shown that the strength of this rhetoric in Protestant thought is neither specific to Bale nor incidental to religious polemic.4 Rather, it was a vital element of a new, defiantly Protestant religious history, and of a broader apocalyptic reading of worldly events that aimed to map ecclesiastical history onto the prophetic symbolism contained in the Book of Revelation. In particular, from the early Henrician Reformation onwards, English apocalyptic thought tried to use the sevenfold pattern of vials and trumpets in Revelation as a guide to the historical stages that would lead to the destruction of the Roman Church. Although it was common, following Revelation, to identify Rome as Babylon in this apocalyptic tradition, it was also important to portray it as a spiritual Sodom and to explore the nature of the latter’s “sodomy.” The identification of both iniquitous cities as the same place—popish Rome—was often mutually reinforcing. Countless Protestant commentaries on Revelation in the two centuries following the Reformation made the point that the Roman Church, identified as Sodom in Revelation 11:8, was in fact the modern antitype of the biblical city in both a spiritual and literal sense and that confronting this sink of iniquity was a crucial stage in the final defeat of the false church. Moreover, because of its link to parts of Saint John’s Apocalypse, the idea of Sodom and the enumeration of its sins played a key role in the prophetic chronologies based on Revelation that were set out in various ways throughout the seventeenth century. “Popery” clearly had a variety of incarnations in the two centuries after the Reformation, and whether Babylon was located in Rome or at the heart of the English church or state also divided Protestants in this period. Popery could be defined in simple terms as the jurisdiction and rule of the pope or from the point of view of Elizabethan and Jacobean puritans as the remnants of Catholic ritual and liturgy in what was seen as the insufficiently reformed Church of England. In the later seventeenth century, popery could also be a more general supremacy of church over state or from a Nonconformist perspective the rule of episcopacy in the church. Since it could also be anything that undermined what was held to be true (namely, Protestant) religion, popery could also be charged against the most extreme Protestant sects. In political terms popery was the twin of “arbitrary government” and was therefore part of a more general threat to liberty. It certainly did not necessarily have to be associated with Rome in order to be demonized, but attacks on its Catholic original reiterated the tendency of popery toward moral iniquity, including lust in all its forms. The power of this way of thinking is shown by the persistence and vitality of antipopery right into the nineteenth century.5

The essence of popery as understood by English Protestants was, as Peter Lake points out, that it placed the pope above Christ and thereby gave preeminence to human institutions, ceremonies, and forms of observance, not least the worship of images, bread (in the form of the Eucharist), and other idols. Idolatry was a form of “spiritual whoredom” since it replaced the marriage of the church and its members to Christ with the adoration of objects. According to Saint Paul’s letter to the Romans, God’s punishment for idolatry was excessive lust, and they were connected in most attacks on Catholicism by the unfortunate results of clerical celibacy. The encouragement to fornication that resulted was, for many Protestant writers, a marker of difference between false and true churches. As Parish points out, the papal ban on priestly marriage was held to have led inevitably to broken vows, clerical lust, concubinage, whoredom, and sodomy—and it was employed by writers of the early Reformation as a key indicator of the difference between reformed religion and Rome. William Tyndale, John Bale, and others argued that clerical celibacy was against both the practices of the early church (which in their view permitted clerical marriage) and contrary to Scripture. Compulsory celibacy, and its fruits of sodomy and whoredom, therefore allowed reforming writers to mark the incursion of error and corruption into the church and to demonstrate its progressive domination by Antichrist. These things also fully justified the description of Rome as the Mother of Harlots found in Revelation. In that sense, homoerotic behavior, and the wider fornication of which it was a subset, was vitally important in linking the prophecies of Revelation with the historical events of the present and recent past. They demonstrated the creeping corruption of the pre-Reformation church, which was generally identified with the growing power of the papacy, and which was completed by the decrees against clerical marriage.

Revelation and Antichrist

As it is so central to the post-Reformation conception of history, it will be helpful here briefly to go over the nature of Revelation and its relationship to the idea of Antichrist. Until the Lutheran Reformation, Saint John’s Apocalypse had a doubtful reputation among theologians, being associated with various chiliastic sects. Even Luther had doubts about whether it should be included in the biblical canon and it was largely ignored by Calvin. However, Revelation had a particular appeal to Protestant writers, mainly because it tells of an embattled, godly minority finally triumphing over an implacable and overwhelming enemy. In that sense, Revelation provided Protestants with an account of God’s plan not only for humanity, but specifically for them, a spiritual map that set out the course of earthly events in the past and to come. The biblical book of Revelation is in the form of a vision given to Saint John the Divine, who is instructed by Jesus to record what he sees in a letter to the seven churches of Asia. After a preamble in which John receives his instructions from Christ, in the first ten chapters John sees the symbolically important seals, trumpets, and vials, along with the angels who break them, blow them, or pour them out onto the Earth. Saint John’s vision was usually divided by theologians into two distinct sections. Chapters 4–10 formed a unity known as the sealed book, as its chief symbolism is the opening of seven seals.6 These are followed by a sequence of seven trumpets being sounded, after the last of which woe and disorder are released onto the world as Satan is released—along with locusts and scorpions—from the bottomless pit where he had been confined after his fall from heaven (9:2). This episode was known as the first woe (9:12), with two more to follow soon thereafter. Chapters 10–19 were known as the open book, as the prophecies held to be contained in the sequence of seals and trumpets are fulfilled. In chapter 11, which was a vitally important episode in the English apocalyptic tradition, God sends two witnesses to earth and they give testimony against the beast that rose from the bottomless pit, who then makes war against them and kills them. Their bodies lie in the streets of a “great city,” to be identified “spiritually” but not literally as Sodom and Egypt, “where also our Lord was crucified” (11:8). The corpses remain there for three and a half days, after which they are resurrected and ascend to heaven in a cloud. This was followed by a great earthquake, and the fall of a “tenth part” of the great city, which marked the end of the second woe. The episode of the witnesses is a prelude to the final confrontation with Satan, which is dealt with between chapters 13 and 20. Chapter 13 describes the emergence of two beasts and their rule, one who rose out of the sea, “having seven heads and ten horns, and upon his horns ten crowns,” and another with two horns. Drawing on similar symbolism from Daniel, which was in many ways regarded as a parallel text, Protestant commentators interpreted both beasts as aspects of the papacy and its jurisdiction. The key symbolism of the later chapters is the pouring out of the seven vials of God’s wrath upon the earth which begins in chapter 16. The vials bring death and plagues to the beast and his rule, while in the following chapter, similarly beloved by Protestants, the angel with the seventh vial describes the “great whore” with whom the kings of the earth have committed fornication. The whore sits on the beast with seven heads and ten horns. In reformed readings, this imagery cemented the association of fornication and whoredom with the beast-like papacy and the ten European kingdoms (the ten horns) that supported her or were part of the pope’s jurisdiction. On the whore’s forehead is written, “Mystery, Babylon the Great, the mother of harlots and Abominations of the Earth,” and she was said to be “drunk with the blood of the saints.” Finally, Babylon falls (chapter 18:10–24), and Satan is bound for one thousand years in a bottomless pit during which time those who had not worshipped the beast during his rule reign with Christ. This was the literal millennium seen as imminent by countless seventeenth-century English millenarians, some of whom thought that it would presage the actual return of Christ. Satan is then loosed again to take part in a climactic battle and ultimately defeated and cast into a lake of fire along with hell and death. In the final two chapters the world is renewed (“I saw a new heaven and a new earth,” 21:1) and the dead are judged, while the holy city of glass and gold descends from heaven, and time is fulfilled.

Perhaps the most important interpreter of these chapters for the English apocalyptic tradition that saw Revelation as a guide for human history was the twelfth-century Calabrian monk Joachim of Fiore, whose writings inspired many medieval critics of the church and its apparent corruption. Joachim’s significance for Protestants lay principally in his division of history into three phases or “statuses,” each one corresponding to a figure of the Trinity—Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. The last status of the Spirit would be a golden age reached after a period of tribulation under Antichrist that culminated in his final defeat. The history of the church could also be further divided into seven ages beginning with the birth of Christ and corresponding to the seven vials and trumpets mentioned in Revelation. In Joachim’s scheme the last of these, the seventh vial, inaugurated the final status—the age of the Spirit.7 After Joachim, it became more common for critics of the church to use the seven-stage patterns found in Revelation as a guide to the progress of the church toward the final status and the defeat of Antichrist.

An important aspect of Joachim’s prophetic writing was the identification of Antichrist and his progress through the church, though the medieval tradition on which Joachim drew was very different from that later employed by Protestant reformers. Antichrist is identified four times in the Bible: in the First Epistle of John (2:18; 2:22), the Second Epistle of John (1:7), and in Paul’s second letter to the Thessalonians (2:3). In the latter he is identified as a deceiver, the man of sin “who opposeth and exalteth himself above all that is called God . . . so that he as God sitteth in the temple of God, shewing himself that he is God.” In John’s Epistles, Antichrist’s arrival is prophesied, and he is described again as a deceiver and a li...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- CONTENTS

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1. The Roman Sodom

- 2. City of Destruction

- 3. The End of the World

- 4. Laws

- 5. Histories

- 6. Lust and Morality in the (Long) Eighteenth Century

- 7. The Discovery of Sodom, 1851

- Conclusion: The End

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index