- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Imagine a common movie scene: a hero confronts a villain. Captioning such a moment would at first glance seem as basic as transcribing the dialogue. But consider the choices involved: How do you convey the sarcasm in a comeback? Do you include a henchman's muttering in the background? Does the villain emit a scream, a grunt, or a howl as he goes down? And how do you note a gunshot without spoiling the scene?

These are the choices closed captioners face every day. Captioners must decide whether and how to describe background noises, accents, laughter, musical cues, and even silences. When captioners describe a sound—or choose to ignore it—they are applying their own subjective interpretations to otherwise objective noises, creating meaning that does not necessarily exist in the soundtrack or the script.

Reading Sounds looks at closed-captioning as a potent source of meaning in rhetorical analysis. Through nine engrossing chapters, Sean Zdenek demonstrates how the choices captioners make affect the way deaf and hard of hearing viewers experience media. He draws on hundreds of real-life examples, as well as interviews with both professional captioners and regular viewers of closed captioning. Zdenek's analysis is an engrossing look at how we make the audible visible, one that proves that better standards for closed captioning create a better entertainment experience for all viewers.

These are the choices closed captioners face every day. Captioners must decide whether and how to describe background noises, accents, laughter, musical cues, and even silences. When captioners describe a sound—or choose to ignore it—they are applying their own subjective interpretations to otherwise objective noises, creating meaning that does not necessarily exist in the soundtrack or the script.

Reading Sounds looks at closed-captioning as a potent source of meaning in rhetorical analysis. Through nine engrossing chapters, Sean Zdenek demonstrates how the choices captioners make affect the way deaf and hard of hearing viewers experience media. He draws on hundreds of real-life examples, as well as interviews with both professional captioners and regular viewers of closed captioning. Zdenek's analysis is an engrossing look at how we make the audible visible, one that proves that better standards for closed captioning create a better entertainment experience for all viewers.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Reading Sounds by Sean Zdenek in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Communication Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University of Chicago PressYear

2015Print ISBN

9780226312781, 9780226312644eBook ISBN

9780226312811ONE

A Rhetorical View of Captioning

Four New Principles of Closed Captioning

Closed captioning has been around since 1980—it’s not “new media” by any means—but you wouldn’t know it from the passionate captioning advocacy campaigns, new web accessibility laws, revised international standards, ongoing lawsuits, new and imperfect web-based captioning solutions, corporate feet dragging, and millions of uncaptioned web videos. Situated at the intersection of a number of competing discourses and perspectives, closed captioning offers a key location for exploring the rhetoric of disability in the age of digital media. Reading Sounds offers the first extended study of closed captioning from a humanistic perspective. Instead of treating closed captioning as a legal requirement, a technical problem, or a matter of simple transcription, this book considers how captioning can be a potent source of meaning in rhetorical analysis.

Reading Sounds positions closed captioning as a significant variable in multimodal analysis, questions narrow definitions that reduce captioning to the mere “display” of text on the screen, broadens current treatments of quality captioning, and explores captioning as a complex rhetorical and interpretative practice. This book argues that captioners not only select which sounds are significant, and hence which sounds are worthy of being captioned, but also rhetorically invent words for sounds. Drawing on a number of examples from a range of popular movies and television shows, Reading Sounds develops a rhetorical sensitivity to the interactions among sounds, captions, contexts, constraints, writers, and readers.

1.1 Captioners offer interpretations within the constraints of time and space.

A frame from 21 Jump Street showing police officers Schmidt (Jonah Hill) and Jenko (Channing Tatum), dressed in black uniforms with matching black shorts and helmets, riding their police bicycles side by side on the park grass. The bike cops are heading straight for the viewer. A small red light is visible on each bicycle’s handlebars. The cops are peddling to confront a small biker gang smoking pot on the other side of the park. Pounding rock music (uncaptioned) accompanies the pursuit but cuts out momentarily to call attention to the faint bicycle sirens, which sound like children’s toys. The sirens are captioned as (SIRENS WHOOPING SOFTLY), which is supposed to capture the ridiculousness of the scene. Packed into this single caption, then, is the reminder that these are not real cops because real cops would be burning rubber in a patrol car and blaring their sirens. Columbia Pictures, 2012. Blu-Ray. http://ReadingSounds.net/chapter1/#figure1.

This view is founded on a number of key but rarely acknowledged and little-understood principles of closed captioning. Taken together, these principles set us on a path towards a new, more complex theory of captioning for deaf and hard-of-hearing viewers. These principles also offer an implicit rationale for the development of theoretically informed caption studies, a research program that is deeply invested in questions of meaning at the interface of sound, writing, and accessibility.

1. Every sound cannot be closed captioned.

Captioning is not mere transcription or the dutiful recording of every sound. There’s not enough space or reading time to try to provide captions for every sound, particularly when sounds are layered on top of each other in the typical big-budget flick. Multiple soundtracks create a wall of sound: foreground speech, background speech, sound effects, music with lyrics, and other ambient sounds overlap and in some cases compete with each other. Sound is simultaneous; print is linear. It’s not possible to convert the entire soundscape of a major film or TV production into a highly condensed print form. It can also be distracting and confusing to readers when the caption track is filled with references to sounds that are incidental to the main narrative. Caption readers may mistake an ambient, stock, or “keynote” sound (Schafer 1977, 9) for a significant plot sound when that sound is repeatedly captioned. A professional captioner shared the following example with me: Consider a dog barking in an establishing shot of a suburban home. When the dog’s bark is repeatedly captioned, one may begin to wonder if there’s something wrong with that dog. Is that sound relevant to this scene? (See figure 1.2.) Very few discussions of captioning acknowledge or even seem to recognize that captioning, done well, must be a selective inscription of the soundscape, even when the goal is so-called “verbatim captioning.”

2. Captioners must decide which sounds are significant.

If every sound cannot be captioned, then someone has to figure out which sounds should be. Speech sounds usually take precedence over nonspeech sounds, but it’s not that simple. What about speech sounds in the background that border on indistinct but are discernable through careful and repeated listening by a well-trained captioner? Should these sounds be captioned (1) verbatim, (2) with a short description such as (indistinct chatter), or (3) not at all? Answering this question by appealing to volume levels (under the assumption that louder sounds are more important) may downplay the important role that quieter sounds sometimes play in a narrative (see figure 1.3). What is needed is an awareness of how sounds are situated in specific contexts. Context trumps volume level. Only through a complete understanding of the entire program can the captioner effectively interpret and reconstruct it. Just as earlier scenes in a movie anticipate later ones, so too should earlier captions anticipate later ones. In the case of a television series, the captioner may need to be familiar with previous episodes (including, when applicable, the work of other captioners on those episodes) in order to identify which sounds have historical significance. The concept of significance (or “relevant” sounds [see Sydik 2007, 181]) shifts our attention away from captioning as copying and toward captioning as the creative selection and interpretation of sounds.

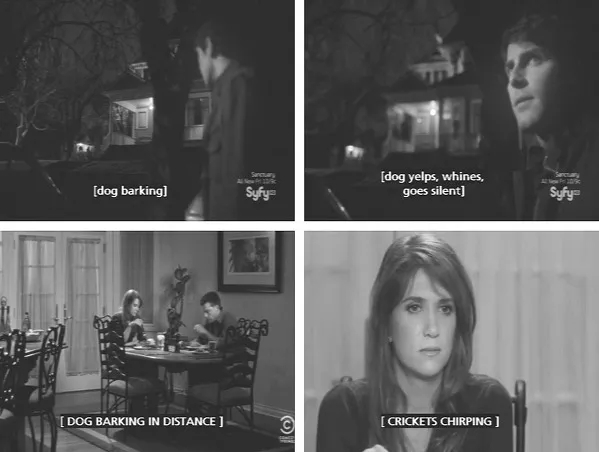

1.2 All dog sounds are not created equal.

The top row contains two frames from an episode of Grimm (2011, season 1, episode 1, NBC). In the top left frame, Nick (David Giuntoli) is shown in profile walking at night on a suburban street. A home in the background is lit by porch light. Large trees provide an ominous backdrop. The caption, [dog barking], is more than a stock sound to provide suburban ambience. A few seconds later in this scene, the same dog seems to be suffering, drawing the attention of Nick, who turns to face the camera in the top right frame. The accompanying caption is [dog yelps, whines, goes silent]. The bottom row contains two frames from Extract (2009, Ternion Pictures), both of which are taken during a dinner table scene at night. In the bottom left frame, Joel (Jason Bateman) and Suzie (Kristen Wiig) are eating at their dining table with the [DOG BARKING IN DISTANCE]. In the bottom right frame, Suzie stares blankly after Joel walks away from the table upset. The accompanying caption: [CRICKETS CHIRPING]. The dog barking in Extract is part of a stock soundscape that includes crickets chirping, whereas the dog sounds are an integral element of the horror storyline in the Grimm episode. The animal and insect captions in Extract end up intruding into the serious dinner discussion. TV source: Extract rebroadcast on Comedy Central and Grimm rebroadcast on the Syfy channel. http://ReadingSounds.net/chapter1/#figure2.

3. Captioners must rhetorically invent and negotiate the meaning of the text.

The caption track isn’t a simple reflection of the production script. The script is not poured wholesale into the caption file. Rather, the movie is transformed into a new text through the process of captioning it. In fact, as we will see in chapter 4, when the captioner relies too heavily on the script (for example, mistaking ambient sounds for distinct speech sounds), the results can be disastrous. In other cases, words must be rhetorically invented, which is typical for nonspeech sounds. I don’t mean that the captioner must invent neologisms—I issue a warning about neologistic onomatopoeia in chapter 8. Rather, the captioner must choose the best word(s) to convey the meaning of a sound in the context of a scene and under the constraints of space and time. The best way to understand this process, as this book argues throughout, is in terms of a rhetorical negotiation of meaning that is dependent on context, purpose, genre, and audience.

4. Captions are interpretations.

Captioning is not an objective science. The meaning is not waiting there to be written down. While the practice of captioning will present a number of simple scenarios for the captioner, the subjectivity of the captioner and the ideological pressures that shape the production of closed captions will always be close to the surface of the captioned text. The practice of captioning movies and TV shows is typically perfo...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- 1 A Rhetorical View of Captioning

- 2 Reading and Writing Captions

- 3 Context and Subjectivity in Sound Effects Captioning

- 4 Logocentrism

- 5 Captioned Irony

- 6 Captioned Silences and Ambient Sounds

- 7 Cultural Literacy, Sonic Allusions, and Series Awareness

- 8 In a Manner of Speaking

- 9 The Future of Closed Captioning

- Acknowledgments

- Bibliography

- Index