eBook - ePub

Drunk Driving

An American Dilemma

James B. Jacobs

This is a test

Share book

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Drunk Driving

An American Dilemma

James B. Jacobs

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

In this ambitious interdisciplinary study, James B. Jacobs provides the first comprehensive review and analysis of America's drunk driving problem and of America's anti-drunk driving policies and jurisprudence. In a clear and accessible style, he considers what has been learned, what is being done, and what constitutional limits exist to the control and enforcement of drunk driving.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Drunk Driving an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Drunk Driving by James B. Jacobs in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Law & Law Theory & Practice. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

I

The Anatomy of a Social Problem

The first four chapters of this book provide the essential background that is necessary to understand the anatomy of drunk driving as a social problem.

Chapter 1 places drunk driving in the context of America’s relationship with alcohol and, more particularly, in the context of its alcohol abuse problem. Beverage alcohol plays a pervasive role in American social and economic life; DWI is a negative consequence of that role. Moreover, alcoholism and alcohol abuse are one of the nation’s major health problems; DWI is but one manifestation of that problem.

Chapter 2 places drunk driving in the context of America’s transportation system. That system provides unparalleled opportunity for individuals to move from place to place in pursuit of their individual and collective goals. Unfortunately, it also generates a toll in life and property that in magnitude can only be compared to casualties in warfare. In the rush to solve the drunk driving problem, we sometimes forget that the ultimate goal is to make the transportation system safer. Preventing and controlling drunk driving is but a subissue in the social control of vehicular traffic.

Chapter 3 focuses on drunk driving as a cause of highway casualties. To what extent are the drunk driving and highway safety problems identical—or at least overlapping? We will see that there is no simple answer to this question; and the question itself conceals several subtle assumptions that need to be examined. In any event, the magnitude of the drunk driving problem has been as much a subject of politics and politicization as of scholarly study and analysis.

Chapter 4 turns to the criminology of drunk driving, patterns of offending, and characteristics of offenders. What do we know about the frequency of this crime and about its offenders? Once again we will encounter a curious paradox: there is both too much and too little information, too many and too few studies. Nevertheless, there are some myths that can be readily dispelled and some basic facts that will prove useful in helping us to analyze the legal and public policy issues that are raised in Parts II and III.

1

Alcohol in American Society

Beverage alcohol plays a central role in American life and culture (see Lender and Martin 1982). It is an accompaniment of celebrations, leisure activities, fine dining, romance, and business deals. Its role is so pervasive and important that its absence in many social situations would be defined as inappropriate and deviant. In short, we Americans live in an alcohol-rich environment.

Alcohol consumption and intoxication also serve important psychological and emotional functions.1 Drinkers seek reduction of tension, guilt, anxiety, and frustration. From personal experience and from viewing countless television and movie dramas, we have become accustomed to people turning to alcohol to cope with a hard day, family problems, or bad news. People also imbibe alcohol to loosen up, let down their hair, release inhibitions, and enhance fantasy and sensuality. Thus we are accustomed to drinking as a prelude to seduction or romance. In addition, people turn to alcohol to fortify confidence, enhance self-esteem, and increase aggressiveness. It seems normal for people to have a drink before proposing marriage, asking the boss for a raise, or going into battle.

The chemical ingredient that gives alcoholic beverages their intoxicating effect is ethyl alcohol (Olson and Gerstein 1985). Beer is generally 3–6 percent alcohol by volume, with light beer at the low end and malt liquor at the high end; wine is generally 10–20 percent alcohol, with table wine low and fortified dessert wine high; and spirits are generally bottled at 40 percent alcohol (80 proof). Despite these differences in alcoholic content per volume, alcoholic drinks generally contain approximately the same alcoholic content. A 12-ounce can of 4-percent beer, a 4-ounce serving of 12-percent wine, and a cocktail with 1.2 ounces of 80-proof spirits contain identical amounts of ethyl alcohol. One drink of any of these alcoholic beverages usually contains about one-half ounce of pure alcohol. While drinkers can and do become intoxicated by drinking all types of alcoholic beverages, wine drinking is more likely to be an accompaniment to meals and not a means of intoxication. Spirits drinking, while by no means always associated with intoxication, provides a method of becoming intoxicated very quickly. Because beer so dominates the alcoholic beverage scene in the United States, it is not surprising that most alcohol abusers are beer abusers.

Patterns of Alcohol Consumption

Alcohol consumption is not unique to American society. In fact, the drinking practices that immigrants brought to America continue to be reflected in different ethnic drinking customs and patterns. Nevertheless, there are certain distinctive features of the American drinking environment—for example, a distinctive mix of spirits, beer, and wine; a large tavern and bar culture; and drunkenness as a social activity for certain segments of the population.

There are large differences in consumption patterns within the United States. The northeastern states show the highest per-capita rates of consumption, the south-central states the lowest. The mid-Atlantic states have the lowest proportion of abstainers, the southern Bible Belt states the highest. There are also wide differences in the rates of alcohol abuse among ethnic groups, with Jews and Italians showing far less dangerous drinking than the Irish.

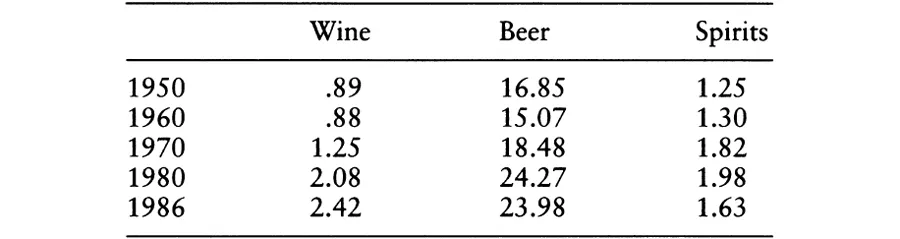

The levels of consumption in colonial America have never been surpassed; for eighteenth-century Americans alcohol was considered safer and healthier than water. During the nineteenth century per-capita alcohol consumption declined from the astronomical rates of the colonial period. From 1850 to 1914 the per-capita consumption hovered around two gallons. Consumption decreased markedly during Prohibition, but since 1946 it has risen steadily to about 2.7 gallons per capita (Gerstein 1981; Malin et al. 1982) (see table 1.1). Per-capita alcohol consumption has increased approximately 35 percent since the early 1960s but has increased only slightly and perhaps has leveled off since the early 1970s. While wine drinking has increased somewhat, there has been a steady decline in the consumption of whiskey and other spirits. Today, in comparison with other Western societies, Americans are not problem drinkers. In per-capita alcohol consumption we rank far below the Italians, French, Portuguese, and Germans. Nevertheless, per capita, Americans consume more alcoholic beverages than they do milk; and the number of Americans either referring themselves or being referred by others to alcohol treatment programs has vastly increased over the past decade (Weisner and Room 1984).

Table 1.1. Alcohol Consumption per Capita 1950–86 (Gallons per Capita)

Source: Distilled Spirits Council of the United States

While the other heavy-drinking countries consume most of their alcohol in beers and wines, Americans drink comparatively more whisky and other distilled spirits, although beer drinking exceeds the drinking of wine and spirits combined.

American alcohol consumption is unusual in the high percentage of abstainers in the adult population; approximately one-third of the population abstains completely, female abstainers (42 percent) outnumbering male abstainers (27 percent) by about three to two. Another third of the population reports drinking, on average, fewer than three drinks per week. The next fifth or so of the population averages about two drinks per day. About the next tenth of all adults averages three or more drinks per day. Finally, the remaining 1–4 percent of the population averages ten or more drinks per day (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 1983; Olson and Gerstein 1985). Thus the per-capita alcohol consumption statistic is primarily affected by the drinking behavior of the heaviest 5–10 percent of drinkers, who account for more than half of all alcoholic beverages consumed.

The Business of Alcohol

Not surprisingly, alcohol is big business. The industry is composed of brewers (beer), distillers (whiskey), and vintners (wine); importers and distributors; and a vast infrastructure of liquor stores, taverns, bars, and restaurants. Like any other industry, its goal is to sell as much of its product as possible. A principle marketing strategy is intensive advertising, linking alcoholic beverages to positive cultural symbols and psychological needs (Jacobson, Atkins, and Hacker 1983). Another marketing strategy is to make drinking and drinking environments as desirable, attractive, and competitive as possible. All told, Americans annually spend $60 billion on alcoholic beverages.

Liquor advertising links beverage alcohol consumption to sex, power, success, esteem, patriotism, thrills, risk taking, relaxation, and practically every other positively valued cultural symbol (see Jacobson, Atkins, and Hacker 1983). Alcohol is suggested as a solution to life’s stresses and disappointments. The alcohol industry, supported by a body of advertising research, has long claimed that alcohol advertising is meant to compete for the patronage of existing drinkers (brand loyalty), not to bring new drinkers into the fold or to increase the consumption of present drinkers. Whatever is meant by “meant,” it is hard to take this claim seriously; but even if we do there is no reason to believe that advertising is so surgically precise that its messages can carefully bypass certain segments of the population and strike only intended subaudiences.

There is also reason to doubt that the industry has such limited goals. To the contrary, it is quite likely that many or most beverage executives consciously strive to increase both the number of drinkers and their consumption levels. Wine producers are the most explicit about their expansionist goals. They have frequently expressed the view that wine is directly competitive with tea, coffee, and soda and that it should become a staple of the American refrigerator and dinner table. A new generation of light (i.e., carbonated) wines is being marketed in six-packs, cans, and cardboard containers. The advertising campaign accompanying this effort attempts to convince the public that wine drinking need not await special occasions or even meals—that wine should be drunk, like soda, as an accompaniment to recreation or simply to quench thirst.

The impact of advertising on problem drinkers raises the most serious concern. These are the industry’s best customers. The heaviest-consuming 10 percent consume more than 50 percent of all beverage alcohol. It is extremely important for the industry that this group at least maintains its consumption level. This does not mean that evil men in the liquor industry want to produce alcoholics. What they want is to sell alcohol and to produce an impressive bottom line. Their best customers are heavy drinkers and people addicted to alcohol. It would be a disaster for the industry if all alcohol abusers became moderate drinkers.

Magazines compete for alcohol advertising dollars by stressing the number and percent of their readers who drink heavily. Consider the observation of Robert McDowell, Anheuser-Busch group marketing manager. In an article entitled “How We Did It,” published in Marketing Times, he explained the beer company’s strategy for staying on top: “We created a new media strategy to achieve a share of voice dominance within the industry and increased advertising expenditures fourfold with greater sports programming to reach the heavy beer drinker” (Jacobson, Atkins, and Hacker 1983, P.32). As Robert Hammond, Director of the Alcohol Research Information Service, wryly notes, “if all 105 million drinkers of legal age consumed the official ‘moderate’ amount of alcohol, the industry would suffer a whopping 40 percent decrease in the sale of beer, wine, and distilled spirits, based on 1981 sales figures” (Jacobson, Atkins, and Hacker 1983 P. 25).

Youth and Alcohol

Americans grow up in a cultural environment where the transition from soda to alcohol is normal and expected and where alcohol is associated with good times, pleasure, and occupational and social success. Drinking alcohol marks a transition from youth to adulthood, so it is not surprising that many adolescents and teenagers are anxious to begin drinking.

Johnston, O’Malley, and Bachman’s (1985) major study of high school students’ drinking and drinking/driving practices surveyed students in seventy-five high schools in seven states. Students were asked to indicate how many days during the last month (excluding religious services) they drank any beer, wine, or liquor. The students reported that the frequency of their drinking increased throughout the high school years. By age fifteen the majority of both males and females drank on at least one occasion during a given month. More than one-quarter of male high school students age seventeen or older said that they drank on ten or more occasions in a given month. Two of five high school seniors reported that they had five or more drinks on a single occasion during the two weeks prior to the survey. A significant proportion of adolescent binge drinkers claimed that alcohol intoxication is a necessary part of their lives.

Young people are an important market for alcohol advertisers. Producers know that if they can recruit a young drinker they may have a lifetime customer. Therefore they advertise heavily in magazines appealing to young audiences (e.g., National Lampoon, Ms, and Rolling Stone). At least until very recently, many beer companies hired college students to serve as campus representatives, who arrange for beer at campus functions and sponsor youth events such as rock concerts and sports contests.

Television and Alcohol

Television programs (not to mention movies), which the average American watches for six hours per day, also project important messages about alcohol consumption. Dillon (1975) found that 80 percent of prime-time television shows contain alcohol events. One content analysis found that television programs portrayed drinking positively 60 percent of the time and negatively 40 percent of the time (McEwen and Hanneman 1974). A steady television watcher is exposed to a constant imagery of heavy drinking associated with sociability, success, power, sex, and coping. By way of contrast, he or she sees only an occasional public service announcement (PSA) on alcohol. In fact, McEwen and Hanneman (1974) found that not more than 3 percent of alcohol messages were PSAs and that they appeared at the rate of once every sixteen hours of viewing time.

More recently, Wallach, Breed, and Cruz (1987) carried out a content analysis of alcohol episodes that were shown on prime-time television. They found that while depictions of problem drinking are few,

the alcohol message is not neutral. The frequency of drinking acts and the high level of alcohol reflects a “wet” environment which exceeds that of the real world. Conversations are held over drinks, cocktail parties are the setting for action, and bars are commonly seen as background settings for talks and meetings. Alcohol is ubiquitous in television life. The strong suggestion conveyed to viewers is that alcohol is taken for granted, routine and necessary, that most people drink and that drinking is part of everyday life. The drinkers are frequently glamorous; for many viewers they are setting an example regarding lifestyle. (P. 37)

Problem Drinking

In 1978 the NIAAA estimated that, of all Americans who drank, 36 percent could be classified as “either being problem drinkers or having potential problems with alcohol” (10 percent and 26 percent respectively). This translated into approximately 9.3 million to 10 million people or about 7 percent of...