- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

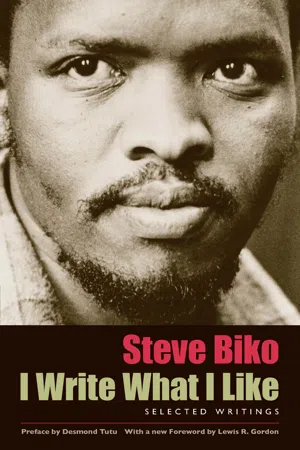

"The most potent weapon in the hands of the oppressor is the mind of the oppressed." Like all of Steve Biko's writings, those words testify to the passion, courage, and keen insight that made him one of the most powerful figures in South Africa's struggle against apartheid. They also reflect his conviction that black people in South Africa could not be liberated until they united to break their chains of servitude, a key tenet of the Black Consciousness movement that he helped found.

I Write What I Like contains a selection of Biko's writings from 1969, when he became the president of the South African Students' Organization, to 1972, when he was prohibited from publishing. The collection also includes a preface by Archbishop Desmond Tutu; an introduction by Malusi and Thoko Mpumlwana, who were both involved with Biko in the Black Consciousness movement; a memoir of Biko by Father Aelred Stubbs, his longtime pastor and friend; and a new foreword by Professor Lewis Gordon.

Biko's writings will inspire and educate anyone concerned with issues of racism, postcolonialism, and black nationalism.

I Write What I Like contains a selection of Biko's writings from 1969, when he became the president of the South African Students' Organization, to 1972, when he was prohibited from publishing. The collection also includes a preface by Archbishop Desmond Tutu; an introduction by Malusi and Thoko Mpumlwana, who were both involved with Biko in the Black Consciousness movement; a memoir of Biko by Father Aelred Stubbs, his longtime pastor and friend; and a new foreword by Professor Lewis Gordon.

Biko's writings will inspire and educate anyone concerned with issues of racism, postcolonialism, and black nationalism.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Biographical Summary

Stephen Bantu Biko was born in Kingwilliamstown, Cape Province, on 18 December 1946, the third child and second son of Mr and Mrs Mzimgayi Biko. His father died when Stephen was four. He received primary and secondary education locally before proceeding to Lovedale Institution, Alice. He did not stay long at that Bantu Education Department-run school however, and his formative higher schooling was received at the Roman Catholic Mariannhill, in Natal. Matriculating at the end of 1965 he entered the medical school of the (white) University of Natal, Non-European section, Durban, at the beginning of 1966. Active at first in NUSAS (National Union of South African Students), he broke with them in 1968 to form SASO (South African Students’ Organisation), of which he was elected first President in July 1969, and in July 1970 he was appointed Publicity Secretary.

In December 1970 he married Miss Nontsikelelo (Ntsiki) Mashalaba from Umtata. From 1971 his heart was increasingly in political activity, and in the middle of 1972 his course at Wentworth was terminated. Immediately he began to work for BCP (Black Community Proggrammes) in Durban, but at the beginning of March 1973, together with seven other SASO leaders, was banned. Restricted to his home town of Kingwilliamstown, he founded the Eastern Cape Branch of BCP and worked as Branch Executive until an extra clause was inserted in his banning order at the end of 1975 prohibiting him from working for BCP.

In 1975 he was instrumental in founding the Zimele Trust Fund. He was detained for 101 days under section 6 of the Terrorism Act from August to December 1976, and was then released without being charged. He was many times charged under security legislation, but never convicted. In January 1977 he was appointed Honorary President of BPC (Black People’s Convention) for five years—an organisation he had helped to found in 1972.

On 18 August 1977, he was again detained under section 6 of the Terrorism Act. He was taken to Port Elizabeth, where he was kept naked and manacled, as was revealed at the inquest after his death. He died in detention on 12 September. The cause of death was established as brain damage. His death and the inquest have been so extensively reported that it is unnecessary to add further details here. He leaves a widow and two small boys aged seven and three.

The writings which follow belong or refer to the period 1969–72, when Steve was active in the Black Consciousness Movement, of which he is now regarded as the “father”. After his banning in March 1973 he could no longer travel, speak in public, or write for publication. It seems logical, therefore, to place these before the memoir, which deals mainly with the period after he was banned. The evidence at the BPC-SASO Trial in Pretoria was given in the first week of May 1976, but refers to events which took place during the earlier period. Thus the book follows a chronological sequence as far as can be ascertained.

2

SASO-its Role, its Significance and its Future

In the early 1960s there had been abortive attempts to found non-white student organisations. In 1961 and 1962 the African Students’ Association (ASA) and the African Students’ Union of South Africa (ASUSA) were established. The Durban Students’ Union and the Cape Peninsular Students’ Union, which later merged to form the Progressive National Students’ Organisation, were fanatically opposed to NUSAS initially. ASA and ASUSA were divided by ideological loyalties connected with (ANC) African National Congress and Pan Africanist Congress (PAC). None of these organisations survived. NUSAS was by no means a spent force on the black campuses, but the fact that its own power base was on white campuses (Wits—the University of Witwatersrand—Rhodes, University of Cape Town, Natal) meant that it was virtually impossible for black students to attain leadership positions. Least of all could NUSAS speak for non-white campuses, though it often assumed that role.

The formation of the University Christian Movement (UCM) in 1967 gave blacks a greater chance of coming together. Its initial political respectability in the eyes of the black university college authorities gave it a chance to function on those campuses in a way impossible for NUSAS. At the UCM Conference at Stutterheim in July 1968 about 40 blacks from all the main black centres of higher education in the Republic formed themselves into a caucus and agreed on the need for a nationally representative black student organisation. The UNB group (University of Natal Black), which of course included Steve, was asked to continue investigations. As a result a representative conference was held at Mariannhill, Natal, in December 1968, when SASO was formed, to be officially inaugurated at Turfloop in July 1969, when Steve was elected President.

This is Steve’s Presidential address to the 1st National Formation School of SASO, held at University of Natal–Black Section, Wentworth, Durban, 1–4 December 1969.

SASO—ITS ROLE, ITS SIGNIFICANCE AND ITS FUTURE

Very few of the South African students’ organisations have elicited as mixed a response on their establishment as SASO seems to have done. It would seem that only the middle-of-the-roaders have accepted SASO. Cries of “shame” were heard from the white students who have struggled for years to maintain interracial contact. From some of the black militants’ point of view SASO was far from the answer, it was still too amorphous to be of any real help. No one was sure of the real direction of SASO. Everybody expressed fears that SASO was a conformist organisation. A few of the white students expressed fears that this was a sign to turn towards militancy. In the middle of it all was the SASO executive. Those people were called upon to make countless explanations on what this all was about.

I am surprised that this had to be so. Not only was the move taken by the non-white students defensible but it was a long overdue step. It seems sometimes that it is a crime for the non-white students to think for themselves. The idea of everything being done for the blacks is an old one and all liberals take pride in it; but once the black students want to do things for themselves suddenly they are regarded as becoming “militant”.

Probably it would be of use at this stage to paraphrase the aims of SASO as an organisation. These are:

1. To crystallise the needs and aspirations of the non-white students and to seek to make known their grievances.

2. Where possible to put into effect programmes designed to meet the needs of the non-white students and to act on a collective basis in an effort to solve some of the problems which beset the centres individually.

3. To heighten the degree of contact not only amongst the non-white students but also amongst these and the rest of the South African student population, to make the non-white students accepted on their own terms as an integral part of the South African student community.

4. To establish a solid identity amongst the non-white students and to ensure that these students are always treated with the dignity and respect they deserve.

5. To protect the interests of the member centres and to act as a pressure group on all institutions and organisations for the benefit of the non-white students.

6. To boost up the morale of the non-white students, to heighten their own confidence in themselves and to contribute largely to the direction of thought taken by the various institutions on social, political and other current topics.

The above aims give in a nutshell the role of SASO as an organisation. The fact that the whole ideology centres around non-white students as a group might make a few people to believe that the organisation is racially inclined. Yet what SASO has done is simply to take stock of the present scene in the country and to realise that not unless the non-white students decide to lift themselves from the doldrums will they ever hope to get out of them. What we want is not black visibility but real black participation. In other words it does not help us to see several quiet black faces in a multiracial student gathering which ultimately concentrates on what the white students believe are the needs for the black students. Because of our sheer bargaining power as an organisation we can manage in fact to bring about a more meaningful contact between the various colour groups in the student world.

The idea that SASO is a form of “Black NUSAS” has been thrown around. Let it be known that SASO is not a national union and has never claimed to be one. Neither is SASO opposed to NUSAS as a national union. SASO accepts the principle that in any one country at any time a national union must be open to all students in that country, and in our country NUSAS is the national union and SASO accepts her fully as such and offers no competition in that direction. What SASO objects to is the dichotomy between principle and practice so apparent among members of that organisation. While very few would like to criticise NUSAS policy and principles as they appear on paper one tends to get worried at all hypocrisy practised by the members of that organisation. This serves to make the non-white members feel unaccepted and insulted in many instances. One may also add that the mere numbers fail to reflect a true picture of the South African scene. There shall always be a white majority in the organisation. This in itself does not matter except that where there is conflict of interests between the two colour groups the non-white always get off the poorer. These are some of the problems SASO looks into. We would not like to see the black centres being forced out of NUSAS by a swing to the right. Hence it becomes our concern to exert our influence on NUSAS where possible for the benefit of the non-white centres who are members of that organisation.

Another popular question is why SASO does not affiliate to NUSAS. SASO has a specific role to play and it has been set up as the custodian of non-white interests. It can best serve this purpose by maintaining only functional relationships with other student organisations but not structural ones. It is true that one of the reasons why SASO was formed was that organisations like NUSAS were anathema at the University Colleges.* However our decision not to affiliate to NUSAS arises out of the consideration of our role as an organisation in that we do not want to develop any structural relationships that may later interfere with our effectiveness.

SASO has met with a number of difficulties shortly after its inception.

1. There is the chronic problem of not having enough financial resources. It does seem that this is where most non-white organisations fail. However we hope to clear out of this difficulty soon and we shall in the process need lots of help from the stronger centres.

2. Traditional sectionalisation still makes correspondence a very sluggish business with some centres. Most of the university colleges have a long history of isolation. Some of them have grabbed the chance to break free from their cocoons. A few still cling tenaciously to them. We have for instance been unable to get through to Bellville. We have difficulty in getting to a few other centres. But I am happy to say that most centres realise the exciting possibilities of this meaningful form of communication. We hope in time that we shall all be able to join in the happy community of those who share their problems.

3. The bogey of authority also seems a real problem. Understandably lots of students are afraid that any involvement with anybody beyond their own university might attract unwarranted attention not only from local but also from national authority. However one hopes that there will be more examples of those courageous few who built up the SRC at places like Turfloop to the point where it had a lot of bargaining power with the Rector.

4. Non-acceptance by NUSAS sparked off lots of unwelcome problems. To many centres accepting SASO became an automatic step towards Withdrawing from NUSAS. Very few centres seemed to be able to grasp the differences in focal points between the two organisations.

5. There has been considerable lack of support from the various SRCs for those involved in the organisation. A lot of people even from the affiliated centres seem to regard themselves as observers.

However besides these problems the Executive has continued applying itself diligently towards setting a really solid foundation for the future. There is reason to believe that SASO will grow from strength to strength as more and more centres join.

The future of SASO highly depends on a number of things. Personally I believe that there will be a swing to the right on the white campuses. This will result in the death of NUSAS or a change in that organisation that will virtually exclude all non-whites. All sensible people will strive to delay the advent of that moment. I believe that SASO too should. But if the day when it shall come is inevitable, when it does come SASO will shoulder the full responsibility of being the only student organisation catering for the needs of the non-white students. And in all probability SASO will be the only student organisation still concerned about contact between various colour groups.

Lastly I wish to call upon all student leaders at the non-white institutions to put their weight solidly behind SASO and to guarantee the continued existence of the organisation not only in name but also in effectiveness. This is a challenge to test the independence of the non-white student leaders not only organisationally but also ideologically. The fact that we have differences of approach should not cloud the issue. We have a responsibility not only to ourselves but also to the society from which we spring. No one else will ever take the challenge up until we, of our own accord, accept the inevitable fact that ultimately the leadership of the non-white peoples in this country rests with us.

3

Letter to SRC Presidents

This chapter consists of a letter sent by Steve, as President of SASO, in February 1970 to the SRC (Students’ Representative Council) Presidents of English and Afrikaans medium universities, to national student and other (including overseas) organisations. It gives the historical background and an authoritative rationale for the founding of SASO. The tone is conciliatory towards NUSAS, which is still recognised as “the true National Union of students in South Africa today”. Steve was aware of the strength of opposition to a segregated body, particularly outside South Africa which is where it was hoped that some of the money for the support of SASO would come from. It was necessary to present the positive purpose in the formation of SASO which would make it clear that the “withdrawal” was only in order to re-group and be more effective in striving towards the common ultimate aim of both NUSAS and SASO–anon-racial, egalitarian society.

The historical background section displays Steve’s strong sense of history and particularly of the continuity of African resistance to the various forms of white oppression. In reading this document readers should remember that from his first arrival at Medical School Steve had taken a leading part in NUSAS activities, and had been an outstandingly successful NUSAS local Chairman. It could never be said of him that he turned to founding a rival organisation because of his failure to “make the grade” in NUSAS. Also it is remarkable, but entirely typical, that the implicit attack on NUSAS which the founding of SASO involved never led to a breach of the good personal relationships he ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Copyright

- Title Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Foreword

- Editor’s Preface

- Preface

- Introduction

- Glossary

- 1. Biographical Summary

- 2. Saso—its Role, its Significance and its Future

- 3. Letter to SRC Presidents

- 4. Black Campuses and Current Feelings

- 5. Black Souls in White Skins?

- 6. We Blacks

- 7. Fragmentation of the Black Resistance

- 8. Some African Cultural Concepts

- 9. The Definition of Black Consciousness

- 10. The Church as seen by a Young Layman

- 11. White Racism and Black Consciousness

- 12. Fear—an Important Determinant in South African Politics

- 13. Let’s talk about Bantustans

- 14. Black Consciousness and the Quest for a True Humanity

- 15. What is Black Consciousness?

- 16. ‘The Righteousness of our Strength’

- 17. American Policy towards Azania

- 18. Our Strategy for Liberation

- 19. On Death

- Martyr of Hope: A Personal Memoir by Aelred Stubbs C.R.

- Notes

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access I Write What I Like by Steve Biko, Aelred Stubbs, C.R. in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social Science Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.