- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Robert Paul and the Origins of British Cinema

About this book

The early years of film were dominated by competition between inventors in America and France, especially Thomas Edison and the Lumière brothers . But while these have generally been considered the foremost pioneers of film, they were not the only crucial figures in its inception. Telling the story of the white-hot years of filmmaking in the 1890s, Robert Paul and the Origins of British Cinema seeks to restore Robert Paul, Britain's most important early innovator in film, to his rightful place.

From improving upon Edison's Kinetoscope to cocreating the first movie camera in Britain to building England's first film studio and launching the country's motion-picture industry, Paul played a key part in the history of cinema worldwide. It's not only Paul's story, however, that historian Ian Christie tells here. Robert Paul and the Origins of British Cinema also details the race among inventors to develop lucrative technologies and the jumbled culture of patent-snatching, showmanship, and music halls that prevailed in the last decade of the nineteenth century. Both an in-depth biography and a magnificent look at early cinema and fin-de-siècle Britain, Robert Paul and the Origins of British Cinema is a first-rate cultural history of a fascinating era of global invention, and the revelation of one of its undervalued contributors.

From improving upon Edison's Kinetoscope to cocreating the first movie camera in Britain to building England's first film studio and launching the country's motion-picture industry, Paul played a key part in the history of cinema worldwide. It's not only Paul's story, however, that historian Ian Christie tells here. Robert Paul and the Origins of British Cinema also details the race among inventors to develop lucrative technologies and the jumbled culture of patent-snatching, showmanship, and music halls that prevailed in the last decade of the nineteenth century. Both an in-depth biography and a magnificent look at early cinema and fin-de-siècle Britain, Robert Paul and the Origins of British Cinema is a first-rate cultural history of a fascinating era of global invention, and the revelation of one of its undervalued contributors.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Robert Paul and the Origins of British Cinema by Ian Christie in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Modern British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

• CHAPTER 1 •

Getting into the Picture Business

One of the most famous anecdotes in early cinema history involves Robert Paul. It seems too improbable to be true, but this apparently is what happened. Two mysterious businessmen, of Greek origin but from New York, call on Paul at his Hatton Garden engineering business in 1894 and invite him to replicate or copy the latest mechanical marvel, Thomas Edison’s Kinetoscope. To his surprise, he finds there is no legal obstacle and proceeds to do so, initially for the Greeks, then for himself and other customers in Britain and beyond.1 And so a career in “animated photography” was launched, with London becoming one of the capital cities of the new era.

But what was the Kinetoscope? A primitive forerunner of cinema proper, or a magic box that first revealed the potential of moving pictures? During much of the twentieth century, it seemed to belong firmly to the primitive category, part of the vast lumber-room of “pre-cinema” devices that preceded the real thing. But now that the “real thing” has splintered into so many different forms of delivery, from giant IMAX screens to mobile phone displays, we are free look afresh at the Kinetoscope and realize what an important step it marked. For two years, till the end of 1895, it was hailed as the marvel of the age. It was not yet the forerunner of projected moving pictures, which didn’t exist, except fitfully in the workshops and dreams of a few scattered experimenters. Rather, it was moving pictures, and it remained the reference point when projection first appeared.

The Magic Box

The Kinetoscope resulted from some five years of trial and error by Thomas Edison and members of his staff at West Orange, New Jersey. Technically and conceptually, their experiments built upon a series of scientific discoveries about vision made early in the century, and the family of popular “optical toys” that followed.2 But for Edison, its immediate origins lay in the astonishing success of his Phonograph, which had aroused worldwide admiration for “the wizard” in 1877. The first versions of the Phonograph used tinfoil-covered cylinders and produced very limited sound quality, adequate for speech recording but not for music; it was clearly the idea of being able to capture and store sound, the potential of this new magical instrument—the second modern time-shifting device to appear after photography—that mattered. Nonetheless, even before Edison introduced a “perfected” version in 1888, the Phonograph had captured the world’s imagination and inspired ideas for its use that ranged from attaching it to the front door to take callers’ messages, or combining it with the newly invented telephone, to ambitious schemes for long-distance medical diagnosis, and even, as an extension of Victorian “memorial culture,” fantasies of communicating with the dead.3

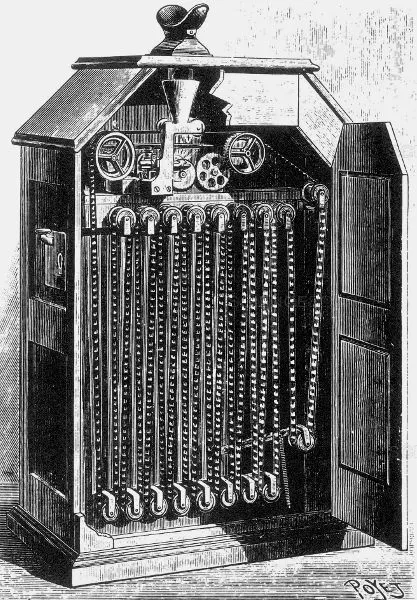

2. Early publicity illustration of Edison’s Kinetoscope viewer, showing its continuous filmstrip.

In 1888, after a meeting with the photographer Eadweard Muybridge, who was showing sequential photographs of figures in motion using a projection version of the phenakistiscope optical toy, Edison announced that he planned “to do for the eye what the Phonograph did for the ear,” in other words to offer continuous recording.4 He set his assistants to work on a device that would use the same cylinder format, with a spiral of images wrapped around it, although the search for a workable system would eventually lead to a flexible band or strip, passing over rollers. Most of the actual development was led by the French-born Scot William Dickson, who adopted a new transparent material, celluloid, that offered strength and flexibility, while accepting photographic emulsion.5 And so the basic format of the motion-picture “film” was born. Indeed, Dickson’s decisions on the strip’s width and perforated holes on either side to allow the film to be moved by sprocket wheels became standard and universal for a century, as did the principle of creating sequential images and changing these sufficiently fast for spectators to experience the illusion of a continuous moving reality.

But although the Phonograph had led Edison to the Kinetoscope, there was another midcentury invention that arguably did as much to create an appetite for lifelike reproduction of the visible world. The stereoscope tricked the eye in another way, by using two photographic images taken from slightly separated viewpoints, which when seen through a special viewer offered the illusion of a “solid,” three-dimensional image. Developed from Charles Wheatstone’s initial study of stereopsis in normal vision in 1838, the stereoscope would, in various forms, become the first widely available instrument of the nineteenth-century media revolution during the 1860s and 1870s. Many hundreds of thousands of viewers were produced according to the Brewster or Bates-Holmes pattern, and the total number of stereograph cards in circulation must have run into millions, ranging from famous places and sights to works of art and biblical scenes, and from exotic peoples pictured by explorers to erotic poses for private consumption6 The illusion only works if the viewing device is held close to both eyes, providing an intensely personal experience in which normal perception is suspended; the user’s immediate surroundings are replaced by a specially arranged image that appears “super-real.”

One of the earliest enthusiasts for the stereoscope was the American poet and essayist Oliver Wendell Holmes, who wrote evocatively of the experience in 1859:

The mind feels its way into the very depths of the picture. The scraggy branches of a tree in the foreground run out at us as if they would scratch our eyes out. The elbow of a figure stands forth so as to make us almost uncomfortable. Then there is such a frightful amount of detail, that we have the same sense of infinite complexity which Nature gives us.7

Not everyone shared this enthusiasm, especially for the sheer scale of its adoption. The poet Charles Baudelaire, skeptical about the impact of new technologies on art, while also aware of the bond that is formed with toys in childhood, wrote contemptuously of “thousands of greedy pairs of eyes bent to the stereoscope’s openings as to the skylight to infinity.”8 But the meteoric success of the stereoscope as a new way of seeing and a device that redefined both the spectator—who became a kind of voyeur—and the spectacle, may be a better pointer than the phonograph toward the appetite for visual novelty and entertainment that moving pictures would satisfy.9

Another, older visual device had simultaneously been undergoing spectacular changes. The magic lantern dated back to the seventeenth century, but the nineteenth century brought dramatic improvements in what had hitherto been largely a domestic entertainment. New forms of illumination, especially “limelight,” enabled lanterns to show large, bright images before vastly increased audiences. From the 1840s onward, photographic slides greatly expanded the repertoire available to lanternists, making possible “travelogues” and narratives using “life models”—both genres that also flourished in stereoscopic form, and would continue into the moving-picture era. Double and triple lanterns became increasingly popular, allowing lanternists to project elaborate sequences of “dissolving views,” which implied the passing of time. And “slipping slides,” with moving parts, became increasingly ingenious, with gear-driven kaleidoscopic “chromatropes” and mechanisms making possible the illusion of anecdotal movements—such as a “man swallowing rats.” Cumulatively, by the closing decades of the century these developments had made the newly renamed “optical lantern” (or “stereopticon” in the United States) a versatile device, capable of creating many kinds of spectacle and offering an immersive experience to large audiences. Projected moving pictures too would depend upon the lantern, with an extended period when slides and moving pictures were projected alternately from the same dual-purpose device.10

If the phenakistiscope and its many descendants offered forms of repeatable movement, then the enhanced lantern and stereoscope created a popular taste for different versions of “presence”—of the illusion appearing somewhere other than the place of viewing. There were indeed many attempts to create a stereoscopic form of lantern projection, just as there was early optimism that moving pictures could be taken and shown stereoscopically.11 Although neither proved possible within the parameters of “normal” turn-of-the-century spectatorship, “animated photography” was soon found to provide an attractive and practical hybrid experience.

Thanks to the established popularity of the stereoscope, the Kinetoscope could be developed as a viewing device that required the user to look into a lens to see its moving images. As a technical showpiece, the Kinetoscope featured Edison’s even more famous invention, the incandescent electric light, and was one of the first electrically powered machines to be widely displayed. These novel features compensated for an image that, compared with the stereoscope’s immersive character, was small, needing to be viewed through a magnifying lens, and rather dim (a rotating shutter that segmented the continuously moving film strip blocked much of the light from reaching the viewer). As an economic venture, it was also one of the earliest coin-operated entertainment device, with a business model—a single viewer paying for a brief glimpse of “living pictures”—that both financed the expensive machine and tapped into a popular wave of mechanization, as automatic vending and gambling machines began to appear on both sides of the Atlantic.

The first such machine to be deployed publicly on a large scale was a postcard-vending machine devised by Percival Everitt in 1883. Over a hundred were installed around London, and the US patent was acquired by Thomas Adams to sell his Tutti-Fruiti chewing gum across the New York subway system.12 In the 1890s, Gustav Schultze and Charles Fey began producing automatic gambling machines in San Francisco. Soon Sittman and Pitt’s similar machines were common in New York bars, suggesting a forerunner of the kinetoscope parlor, with its brief bursts of kinetic excitement. In Germany in 1892, Ottomar Anschütz’s electric “Schnellseher”—literally “Rapid Viewer”—showed images on a celluloid disk and was also coin-operated. All of the new American devices used nickels, which may well have guided the Edison laboratory’s decision that the Kinetoscope should take the same coin. And the link between early moving pictures and automated candy sales in particular would continue. The British pioneer (and Paul’s temporary associate) Birt Acres was hired in 1895 by the German chocolate company Ludwig Stollwerck to make films for its Kinetoscope parlors; while in 1897 another American gum company would introduce animated figures as an extra attraction on its vending machines, as if acknowledging Edison’s success.

The Kinetoscope had had a fitful history of development, as Edison’s own interest in it fluctuated over five years while he struggled with other, potentially more lucrative inventions. Delayed beyond its intended launch at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, where the application of electricity was a major theme, it had its first public demonstration in May 1893 at the Brooklyn Academy of Arts and Sciences. Early descriptions of the chest-high wooden cabinet that housed (and hid) the mechanism compared it to “a medium-sized refrigerator” or simply “a nice piece of furniture,” with a peephole or viewing aperture at the top.13 Inside the cabinet, a continuous strip of celluloid passed over a series of rollers at approximately 40 frames per second, the viewer seeing this by means of an electric light powered by batteries and made intermittent by a rotating perforated wheel. Although the Kinetoscope undoubtedly gave an impressive illusion of natural movement, it did not use the intermittent strip-movement principle common to all later projectors and motion-picture cameras.

Like other devices that exploited scientific principles and new technologies, it still enjoyed an ambiguous status, part “demonstration” and part novelty, waiting to see if there was a market. Edison admitted his doubts that it had a commercial future in some early interviews,14 and the fact that he did not seek patent protection beyond the United States has often been attributed to this. Another explanation, however, is that, having spent several years and much staff time on it, he realized some of its features would not be patentable abroad, where other moving-picture devices already used perforated translucent strips and intermittent illumination.15

Whatever the reservations about its potential or parentage, the kinetoscope made its commercial debut in a special “parlor,” or arcade, on Broadway on 14 April 1894. With ten machines, each offering a different subject, the Holland Brothers’ venture proved an immediate success, leading them to open similar parlors in Chicago and San Francisco within six weeks. Unlike much of the subsequent history of moving pictures, the economics of this first phase of exhibition are largely known. The Hollands paid $300 for each machine to the Kinetoscope Company, which in turn bought them for $200 from Edison. Against this relatively high outlay, and the high cost of viewing—5 cents for less than 30 seconds—they apparently grossed an average of $1,400 per month for the first year, which translates to an average of a thousand customers per day.16 Other companies sprang up to open kinetoscope shows in many cities around the world—one o...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Prelude

- chapter 1 Getting into the Picture Business

- chapter 2 Flashback: An Engineer’s Education

- chapter 3 “Adding Interest to Wonder”: The First Year in Film

- chapter 4 Time Travel: Film, the Past, and Posterity

- chapter 5 “True Till Death!” Family Business

- chapter 6 Home and Away: Networks of Nonfiction

- chapter 7 Distant Wars: South Africa and Beyond

- chapter 8 Telling Tales: Studio-Based Production

- chapter 9 “Daddy Paul”: The Cultural Economy of Cinema in Britain

- chapter 10 “My Original Business”: Paul’s Technical and Scientific Work

- chapter 11 Paul and Early Film History

- Epilogue

- appendix a “A Novel Form of Exhibition or Entertainment, Means for Presenting the Same”: Paul’s “Time Machine” Patent Application, 1895

- appendix b Flotation advertisement, 1897

- Robert Paul Productions 1895–1909

- Notes

- Index