eBook - ePub

Solving Problems in Technical Communication

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Solving Problems in Technical Communication

About this book

The field of technical communication is rapidly expanding in both the academic world and the private sector, yet a problematic divide remains between theory and practice. Here Stuart A. Selber and Johndan Johnson-Eilola, both respected scholars and teachers of technical communication, effectively bridge that gap.

Solving Problems in Technical Communication collects the latest research and theory in the field and applies it to real-world problems faced by practitioners—problems involving ethics, intercultural communication, new media, and other areas that determine the boundaries of the discipline. The book is structured in four parts, offering an overview of the field, situating it historically and culturally, reviewing various theoretical approaches to technical communication, and examining how the field can be advanced by drawing on diverse perspectives. Timely, informed, and practical, Solving Problems in Technical Communication will be an essential tool for undergraduates and graduate students as they begin the transition from classroom to career.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Publisher

University of Chicago PressYear

2012Print ISBN

9780226924076, 9780226924069eBook ISBN

9780226924083PART 1

MAPPING THE FIELD

As you learn how to function and advance as a technical communicator, you will develop a range of strategies for investigating and mapping the contours of the field, for creating representations of work activities that bound your professional territory in clear and tangible ways. Although this “explorer” metaphor oversimplifies the process, it is still a highly useful image: you will be looking around with an attentive eye, listening to stories from experienced professionals, making quick copies of the maps other people have created, training yourself to spot important and interesting features of the terrain you will be moving through, and more. And because the terrain of the field is constantly shifting and presenting new challenges, the task of mapmaking will be an ongoing professional activity.

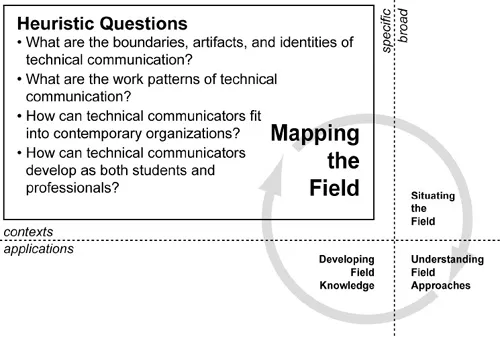

Figure P1.1. Heuristic questions for Mapping the Field

Of course, in most cases, your work as a new technical communicator will not take place in the wild. You will not be the noble, strong-chinned explorer striding in to bring civilization to the natives (that decidedly Western vision always seems to lead to chaos anyway). Instead, you will be working in communities and organizations that are familiar in certain respects and unfamiliar in others. At times, people will talk to you in everyday terms you can understand; at other times, they may seem to speak in another language, referring to strange types of reports and information-gathering strategies, using jargon in dizzying patterns. You will suddenly find yourself in unfamiliar territory and in need of a map (or two). This situation is typical for those new to the field.

Facing new professional challenges can be both energizing and unsettling. Although the chapters in this section (figure P1.1) cannot remove all the uncertainty, they provide heuristics you can use to generate maps to help you find your way around and conceptualize work activities.

In the opening chapter, Richard Selfe and Cynthia Selfe offer an approach to answering one of the first questions you will face: “What Are the Boundaries, Artifacts, and Identities of Technical Communication?” Selfe and Selfe review methods that are commonly employed to help students understand what technical communicators do in the workplace. These methods include examining histories of the field and compiling lists of skills that employers say they want their workers to have. Although these methods are valuable, Selfe and Selfe advocate looking at what technical communicators say to each other about their work, filtering that large and ongoing body of discourse through the information visualization techniques of text clouds to create informative maps of the field. The examples developed by Selfe and Selfe use articles from key journals for practitioners and researchers to create instructive snapshots of professional practice. You can also use these techniques on texts from your own contexts to create different maps of work activities.

In “What Are the Work Patterns of Technical Communication?,” William Hart-Davidson also draws on research by and about practicing technical communicators to define three primary tasks for people in the field: designing information across numerous media and genres, advocating for the needs of users, and stewarding information development in organizations. As Hart-Davidson demonstrates, mapping the functions and value of these activities brings technical communication in from the periphery to occupy a central role in the mission of contemporary organizations. You can use the heuristics offered by Hart-Davidson to develop work processes that encourage and support substantive roles and responsibilities.

This active remapping is demonstrated in detailed ways in “How Can Technical Communicators Fit into Contemporary Organizations?” In this chapter, Jim Henry discusses strategies you can use as you find your way within a new company, community, or organization in your role as a technical communicator. Relying on the experiences of a student team writing an annual report for a community health agency, Henry sketches out heuristics you can draw on as you learn about your first technical communication job and as you move from one organization to another. The heuristics incorporate a variety of qualitative research methods that enable you to map the dynamics and conventions of workplace settings.

The first part of the book concludes with the reminder that mapping the field is an ongoing process that never ends: technical communicators on the job are also always students, learning new ways of working and advancing as situations, goals, and technologies change. Kelli Cargile Cook, Emily Cook, Ben Minson, and Stephanie Wilson address the important question, “How Can Technical Communicators Develop as Both Students and Professionals?” In this chapter, Cook, Minson, and Wilson all look back from their current workplace roles to their time as students in a technical communication class taught by Cargile Cook. As all three demonstrate, effective classroom learning can be useful when you enter the workplace, but you will need to think about the skills and strategies you are transferring, reflecting on how they fit (or fail to fit) with the demands of your current work, adapting and building on them as your own professional abilities evolve and expand. This chapter offers a heuristic that encourages you to constantly update and refine your sense of the field.

1

RICHARD J. SELFE & CYNTHIA L. SELFE

What Are the Boundaries, Artifacts, and Identities of Technical Communication?

SUMMARY

Understanding your field and being able to map the territory of its boundaries, artifacts, and identities is one mark of an informed professional and an important indication of expertise in the workplace. There are numerous ways to define the landscape of technical communication, a field that involves practitioners, researchers, and theorists in a broad range of activities. Some efforts to identify the boundaries of the field rely on historical accounts of how it was born and grew into a recognized area of research and practice. Others describe the research base of technical communication, identifying the topics and issues that provide a focus for investigations and studies. And still other efforts identify the general kinds of skills and understandings needed by technical communicators in the workplace. Each of these approaches has its strengths and limitations, and each produces a very different map of the field.

This chapter focuses on text clouds as away of mapping technical communication and of describing the boundaries, artifacts, and identities that constitute the field. In the following pages, we create text clouds and use them as heuristics to help us discuss the landscape of technical communication.

INTRODUCTION: MAPPING TECHNICAL COMMUNICATION AS A FIELD

In 2006, Amanda Metz Bemer, a student of technical communication at the University of Washington, Seattle, came face to face with an interesting fact about her chosen field: nobody knew what technical communication was. When she talked to her fellow students and friends outside her major, nobody knew what it was that technical communicators really did, nobody knew what research was done in the field, and nobody could imagine what issues interested technical communicators.

Amanda tried to give her friends and family an understanding of the field by listing the classes she had taken: “technical writing, instruction-manual writing, communication theory, usability testing, document design, rhetorical theory.” But, as Amanda noted, she generally got a “blank look and an ‘oh’” for her trouble. So Amanda—asking the question “What the heck is technical communication, anyway?”—wondered if there was a better way to talk about her field than by giving a “laundry list of classes.”

After doing her own research on technical communication—the boundaries of the field, its artifacts, and its identities—Amanda learned that the matter was more complex than she had thought. Indeed, no single source she read had been able to identify a definition of the field that was both comprehensive and specific enough to do justice to the field and help others comprehend what went on within its boundaries.

As Amanda herself noted in “Technically, It’s All Communication: Defining the Field of Technical Communication,” a 2006 article she wrote for Orange, there had been no shortage of attempts to define the boundaries, artifacts, and identities of technical communication. However, the success of each of these attempts, she realized, had been necessarily limited, perhaps because a good map had to serve so many audiences (students of technical communication, scholars and practitioners in the field, nonspecialists and members of the public interested in what technical communication is and isn’t) and perhaps because the field itself covered so much ground. No one map of the territory that the profession occupies had emerged as fully capable of representing so much ground in a concise and understandable way to so many audiences. This is not a flaw of maps as descriptive tools but, rather, a function of their inevitable biases and perspectives. All maps, including the text clouds in this chapter, highlight certain things and not others, depending on the interests and goals of the mapmakers.

The same problem that Amanda identified is shared by many others who study and practice technical communication (Jones 1995), and who argue for the significant benefits of defining the field more clearly. In the following sections, we’ll look at the three primary approaches to mapping the field with words, and then outline a fourth approach—text clouds—that may offer a useful way of responding to Amanda’s question, “What is technical communication anyway?” which, for the purposes of this chapter, we will restate as “What are the boundaries, artifacts, and identities of technical communication?”

The chapter begins with a literature review that describes what scholars and practitioners have already done to define technical communication with words: looking at the history of the field, defining its objects of research, and identifying the skills and understandings that practitioners need to demonstrate. The chapter then looks at text clouds as a heuristic for mapping the field, one that takes advantage of both words and visual information. Finally, the chapter provides an extended example that shows how text clouds might help students like Amanda make sense of technical communication as a field, one that is both complex in scope and dynamic in its practices. Every approach to mapping technical communication, however, has its strengths and weaknesses. As Carolyn Rude (2009, 178) notes, any map of such a large and diverse field is bound to be inherently biased because “some meanings and practices are chosen for emphasis and others are excluded or repressed.” This caveat stands true, as well, for text clouds.

LITERATURE REVIEW: MAPPING THE FIELD OF TECHNICAL COMMUNICATION WITH WORDS

Previous attempts to map the identity of technical communication as a field have generally fallen into three categories: maps that focus on the history of technical communication, maps that describe the research base of technical communication, and maps that identify the skills and understandings needed by technical communicators in the workplace.

HISTORICAL MAPS OF TECHNICAL COMMUNICATION

One way of answering the question, “What are the boundaries, artifacts, and identities of technical communication?” involves tracing the roots of technical communication, creating a map—often in the form of an edited collection of works—that focuses on the historical context of scientific and technical writing and the eventual emergence of the field as we now know it. The strength of historical maps is the careful way in which they capture the social, political, economic, and institutional contexts in which technical communication has been practiced, the motivations and conditions of these practices, the preparation of practitioners, and the various forms and genres that have been developed and deployed by technical communicators. With the information that historical maps of the field provide, we can trace why and how particular genres emerged, learn more about the contributions of individual communicators, and better understand the role that technical communication has played in larger social and cultural movements. These investigations of the past accomplish more than simply providing insights into how the field has changed over the years, as Kynell and Moran (1999) note; they also suggest possible vectors along which the discipline might continue to change in the future.

In Three Keys to the Past: The History of Technical Communication (1999), for example, Teresa Kynell and Michael Moran trace the roots of the profession to the work of natural philosophers, scientists, and educators in past centuries. In this important historical collection, Charles Bazerman writes about the contributions of Joseph Priestley in describing electricity during the seventeenth century; James Zappen explores the science writing and rhetoric of Francis Bacon in the eighteenth century; R. John Brockmann chronicles Oliver Evans’s descriptions of mills and steam engines in the pre–and post–Civil War period of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries; and Teresa Kynell tells the story of Sada Harbarger’s work on promoting technical communication through the Society for the Promotion of Technical Communication in the 1920s.

Despite the many strengths of historical approaches to mapping the field of technical communication, however, histories do have some limitations. As Jo Allen (1999, 227) has pointed out, historical efforts can appear “haphazard”: “Should the work focus on the rise of technical communication as a career; as an academic field of inquiry; or as a centuries-old endeavor . . . ? Should the work examine the subjects, the concept, or the writers of technical communication? And which writers should it examine—those who practiced technical communication or those who have studied it?”

Similarly, when historical accounts focus on key figures, they can encourage what R. John Brockmann (1983, 155) calls a “generals-and-kings” understanding that “history consists of the work of the famous and influential.” In addition, when historical studies focus on key moments of technological innovation (e.g., the invention of the Astrolabe or electricity, the operation of modern mills and steam engines, the publication of the first books on midwifery written by women), they can occasionally encourage disjointed, episodic understandings of technical communication that may, as Jo Allen (1999, 227–228) points out, fail to provide fully situated understandings of how movements develop and are tied to one another.

Those historical accounts that do provide a picture of the long sweep of history, moreover, can suffer from limited detail. Frederick O’Hara’s “Brief History of Technical Communication,” published in 2001, for instance, covers technical communication from the twelfth century to 2005 in four pages. Although short pieces like this one provide valuable thumbnails of broad historical movements, they provide neither the depth of detail nor accurate representations of the many social, cultural, and economic factors that some people might want. If we were to consider this particular brief piece a representative historical map of technical communication, for example, we would only see the largest of landmarks and these only from a distance: the emergence of mathematical writing among the Aztecs, Egyptians, Chinese, and Babylonians; the development of astronomy in the Middle East; the explosion of scientific, medical, and mechanical arts in the Renaissance; the invention of movable type and the growth of scientific publishing in the fifteenth century; the emergence of scientific journals and patents in the eighteenth century; t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Copyright

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Introduction

- Part 1: Mapping the Field

- Part 2: Situating the Field

- Part 3: Understanding Field Approaches

- Part 4: Developing Field Knowledge

- Notes

- List of Contributors

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Solving Problems in Technical Communication by Johndan Johnson-Eilola, Stuart A. Selber, Johndan Johnson-Eilola,Stuart A. Selber in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Linguistics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.