- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Although they entered the world as pure science fiction, robots are now very much a fact of everyday life. Whether a space-age cyborg, a chess-playing automaton, or simply the smartphone in our pocket, robots have long been a symbol of the fraught and fearful relationship between ourselves and our creations. Though we tend to think of them as products of twentieth-century technology—the word "robot" itself dates to only 1921—as a concept, they have colored US society and culture for far longer, as Dustin A. Abnet shows to dazzling effect in The American Robot.

In tracing the history of the idea of robots in US culture, Abnet draws on intellectual history, religion, literature, film, and television. He explores how robots and their many kin have not only conceptually connected but literally embodied some of the most critical questions in modern culture. He also investigates how the discourse around robots has reinforced social and economic inequalities, as well as fantasies of mass domination—chilling thoughts that the recent increase in job automation has done little to quell. The American Robot argues that the deep history of robots has abetted both the literal replacement of humans by machines and the figurative transformation of humans into machines, connecting advances in technology and capitalism to individual and societal change. Look beneath the fears that fracture our society, Abnet tells us, and you're likely to find a robot lurking there.

In tracing the history of the idea of robots in US culture, Abnet draws on intellectual history, religion, literature, film, and television. He explores how robots and their many kin have not only conceptually connected but literally embodied some of the most critical questions in modern culture. He also investigates how the discourse around robots has reinforced social and economic inequalities, as well as fantasies of mass domination—chilling thoughts that the recent increase in job automation has done little to quell. The American Robot argues that the deep history of robots has abetted both the literal replacement of humans by machines and the figurative transformation of humans into machines, connecting advances in technology and capitalism to individual and societal change. Look beneath the fears that fracture our society, Abnet tells us, and you're likely to find a robot lurking there.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The American Robot by Dustin A. Abnet in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART 1

God and Demon

1790–1910

In 1872, Scribner’s Monthly magazine published a strange but illuminating tale with a horrifying ending. Late in 1867, the story told, the sweet and innocent Nellie Swansdown attended an automaton performance in the town of Mullenville with her would-be beau Sam Gumple. As the performance started, the automaton stepped out of a black box “with an air of jaunty assurance, with flaxen hair and whiskers, a nobby suit of clothes, an eye-glass, a cane, and patent leather boots . . . with a bow and a smirk, just as any human being might have done, only with infinitely more grace and ease.” Most of the crowd gaped as the device “ogled the girls . . . cracked jokes with the men . . . danced a hornpipe, and whistled ‘Hail Columbia’ and ‘Yankee Doodle.’” Yet Nellie did not share in the enthusiasm because of a nightmare the previous evening. In her dream, she wed an automaton, but her husband soon “turned into the tall old-fashioned clock which stood in the dining-room; and while she was standing looking up at it in dismay at the thought of being united to such a thing, and bound to honor, love, and obey it all her life, it fell over on to her and crushed her to pieces.” Petrified by her vision of death by clockwork routine, Nellie sat silently through the performance. Her horror increased when the automaton produced a nosegay and threw it into her bosom before disappearing with an “infernal cachinnation, as though some devilish joke were in the wind.” As Sam escorted Nellie home, “a phantom carriage with jet-black horses” approached. From the carriage “sprung a goblin” that Sam “recognized as the automaton.” After knocking Sam out, the automaton “seized Nellie round the waste . . . leaped with her into the phantom coach,” and “disappeared into the night with a rumble like an earthquake.” The town found Sam the next morning raving like a lunatic. Nellie, however, was never seen again; presumably, she was dragged to hell to wed a demon automaton.1

It was a curious tale, made all the curiouser by its author: a former engineer named Julian Hawthorne, the only son of the acclaimed writer of The Scarlet Letter, Nathaniel Hawthorne. Born in 1846, Julian had been raised to appreciate nature, art, and imagination. His formative years had been spent in Concord, Massachusetts, with Nathaniel’s fellow writers Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau, both titans in the transcendentalist religious movement that sought to free the individual from the chains of society through the pursuit of a spiritual connection to nature and the rest of humanity. When Julian was a child, Emerson walked with him through “Fairy Land,” their name for the Walden Woods that Thoreau would later make his home. Also while in Concord, Herman Melville—the fiercest literary critic of industrial capitalism in antebellum America—read Julian bedtime stories. Despite such a background, Julian initially exchanged the worlds of art and literature for the world of civil engineering. With the family financially strapped following his father’s death, Julian chose the regular paycheck offered by a profession at the heart of economic life; further, he reasoned, the job would require him to spend time outdoors, which his father and mentors would appreciate. But Julian was horrible at mathematics, an increasing requirement in the profession, and when his nontechnical job failed to pay him enough to provide for his growing family, he turned to father’s profession.2

This story, “The Mullenville Mystery” was one of his first. Highly experimental, it is told almost entirely in the past tense by an omniscient narrator. Starting the story two months before the fateful automaton performance, the narrator recounts how Nellie hated Sam’s efforts to woo her, but soon met a man brought by the railroad who seemed much closer to her ideal: the “aristocratic” Ned Holland. Unlike Sam, Ned presented an “enterprising countenance and easy confident bearing.” He was, the narrator recalled, “a talented, audacious sort of chap, popular among both men and women,—for there is a large amount of pure romance mingled with his composition, and an impetuosity and fertility of thought and action such as girls always love, and men too, unless they happen to be jealous.”3 The courtship unfolds in a chaste manner appropriate for Victorian middle-class magazines, but then Julian abandons the narration of the past for the structure of a play—complete with parenthetical directions for actions and insights into the characters’ emotional states.

As Nellie and Ned become actors performing roles for the narrator, the two fight over human authenticity. Ned asks, “What is it about me you like the most, Nellie?” To which she jokes about his “rather large” nose as the source of his “conceit.” Offended, he chastises Nellie for her time with Sam. The frustrated Nellie exclaims, “Poor Sam! He’s a human creature, at any rate,—not a machine.” “Furious,” per the stage directions, Ned replies, “Do I understand you to say I’m a machine, Miss Swansdown?” To this, Nellie unleashes a blistering combination of laughter and venom: “You always reminded me so much of a clock!—stuck up to be looked at; wound up to go, and always doing over the same things,—thinking yourself so clever, so accomplished, so knowing, and everybody else so vulgar, so stupid, so commonplace,—oh! You needn’t say anything: one can always tell what a clock is going to say if one can see its face! But really now, Mr. Holland, if you only wouldn’t pretend to be a man, you might be very interesting—as a machine.” After he proposes marriage, she replies, “I’d rather marry an aw . . . awtomaton!” His manhood attacked, the infuriated Ned leaves Nellie with a prophetic: “I trust your wish may be gratified!!”4

This then was the source of Nellie’s descent into an automaton’s hell. Despite appearing amid the heightened industrialization of the post–Civil War years, Julian’s robotic vision was not predominantly a humanized machine but a mechanized human, a man whose external perfection and regularity had made him seem to be performing humanity rather than possessing it. Instead of machines, Nellie was frightened by the regularity and artificiality of the age; that, not the railroad, telegraph, or any other mechanical improvement of the period, gave the automaton its demonic nature.

The contrast with Nathaniel Hawthorne is revealing because he also wrote about an automaton, in his case, a stunningly beautiful clockwork butterfly. Entitled “The Artist of the Beautiful,” the 1844 story recounts the efforts of a skilled but self-absorbed and hubristic clockmaker named Owen Warland to imbue spirit into matter by building a beautiful, living automaton butterfly “that should attain to the ideal which Nature has proposed to herself in all her creatures, but has never taken the pains to realize.” Guided by “Providence” and aided by long walks in nature that invoke the Transcendentalists, Warland eventually succeeds in fusing his “intellect . . . imagination . . . sensibility” and “soul” into the mechanical butterfly, despite the opposition of the town’s utilitarian and materialistic men—a retired master clockmaker and a blacksmith—who see no financial or practical benefit to artistic machinery.5 Though the butterfly is quickly destroyed by the blacksmith’s child, the story suggests that natural and artificial, spirit and matter, beauty and machinery, are not entirely separate entities.6 Fusion is possible, but only under the guidance of God.

Released just after the Civil War, “The Mullenville Mystery” captured subtle but significant transformations in literary critiques of industrial life. Writing near the dawn of American industrialization, Nathaniel Hawthorne, like Emerson and most men of his generation, retained faith in the ability of American institutions and culture to tame machinery in the name of beauty and freedom. As Emerson put it early in his career: “Machinery & Transcendentalism, agree well.” Though he occasionally complained about the railroad, Emerson also believed that transportation and communications improvements could enhance people’s connections to God, nature, and one another to build a harmonious community that still nurtured individual liberty.7 Several decades of industrialization later, Julian Hawthorne told a less optimistic tale about the destruction of human relationships and loss of individual agency. The railroad still brought Ned to Nellie, but their relationship was doomed by his apparent lack of authenticity and their mutual inability to demonstrate agency beyond actions determined by the narrator. Similarly, while both Nathaniel and Julian recognized the magic of the automaton, for the former it remained a potential boon of God if it could be harnessed to the beauty of nature, while for the latter it was a demonic force enchanted by the artificiality of modern life. It is telling that Julian entered engineering believing, as his father did, in the coexistence of nature and mechanics; he left as it became clear that these were two very distinct things.

Between those gaps—natural to mechanical, real to authentic, freedom to determinism, Providence to the devil—lay several of the key tensions facing Americans as they sought to reconcile the development of industrial capitalism and modern science with their longings for a harmonious republican community that nurtured autonomous individuals capable of controlling their own destinies. Merging the worlds of engineering and literature, automatons and the like helped both critics and supporters grapple with the impact of material and intellectual transformations on the individual soul. As they debated the consequences of industrialization on human identity, Americans pondered whether the automaton was a gift of God or a demon that threatened to drag the country’s innocence to hell.

1

The Republican Automaton

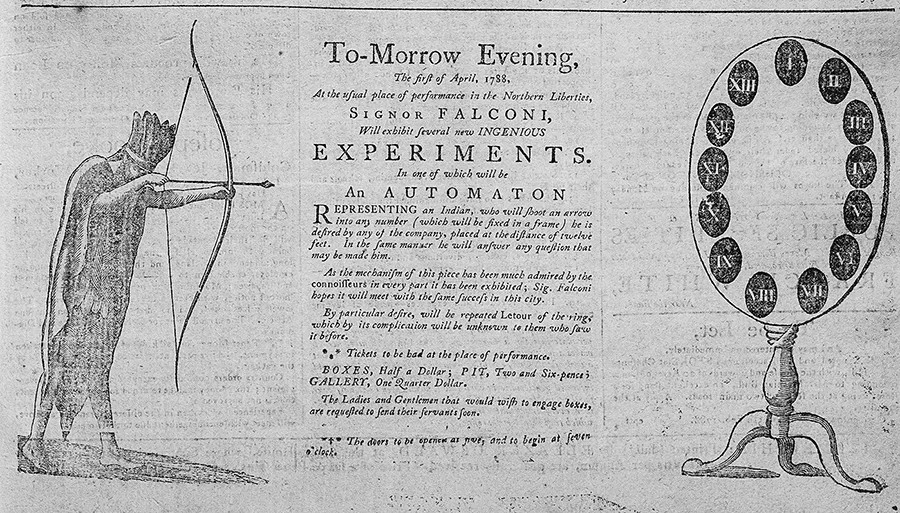

In 1788, newspapers in Philadelphia—the epicenter of the new country’s economic and political life—printed numerous advertisements for an exhibition by “Signor Falconi” that included “INGENIOUS EXPERIMENTS” in catoptrics and electricity, along with an intriguing contraption: an automaton Indian that “will float an arrow into any number (which will be fixed in a frame) he is desired by any of the company, placed at the distance of twelve feet. In the same manner, he will answer any question that may be made him.” To aid comprehension, Falconi included a sketch of the Indian adorned with a feathery headdress aiming an arrow at a circular frame with thirteen numbered targets. “Any Lady,” a later advertisement announced, “may desire the figure to float at a particular number, which it will instantly do with the greatest of exactness. Any person may likewise write one of the numbers painted on the board, which may be folded up, and before it is seen by any one present the figure will strike the number written. And what is more surprising, any of the company may draw two or three dice under a hat, the amount of which the Automaton will strike before they are seen by any person.”1 Here was a performance like few others in the new nation, for it offered an opportunity to indulge, if only for a brief afternoon, in the fantasy of transforming the body of a “savage” Native warrior into a weapon under the command of the audience, especially white women.

Fig. 1.1. A 1788 advertisement for Falconi’s automaton Indian in Philadelphia’s Independent Gazetteer that lays out the performance routine and a two-tiered ticket-pricing scheme that suggests the device attracted multiple social classes. Courtesy of American Antiquarian Society.

The fantasy offered by the automaton inverted the structure of early American captivity narratives in which white settlers, frequently women, were kidnapped and raised by natives. This performance brought the native body into a space where it could be contained by the eyes and voices of Falconi and the audience. Removed from its environment, the Indian did not degenerate into savagery—as many captivity narratives assumed would happen to white settlers—but grew civilized by following the orders of his social superiors. The audience became the rational mind of a creature assumed to be driven by mechanical reflex and violent passions. Though the act acknowledged a degree of contingency inherent in savagery, even rolling the dice left power in the hands of the audience members themselves; they could decide whether to allow the native to indulge in random violence or to force it to follow orders.2

By itself, Falconi’s Indian offered audiences a humorous but powerful fantasy. When connected to the scientific work of the era, however, it became an ideological statement about the nature of people Euro-Americans simultaneously feared and mocked. Several years earlier, one of the most popular European naturalists, Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon, published a series of natural history books on the flora and fauna of the Americas. In one volume, he claimed that the Native American male was “a kind of weak automaton” because of his inability to control himself or nature. For Buffon, who embraced vitalism when discussing Europeans, American Indian men were “mere automatons incapable of correcting Nature or seconding her intention” because “they had no control over either animals or elements; they had neither subjected the waves nor directed the motions of rivers, nor even cultivated the earth around them.” Similarly, because they possessed only small and feeble “organs of generation,” displayed “no ardour for the female,” and were “possessed of less sensibility” than Europeans, they had “no vivacity, no activity of soul and that of body is less a voluntary exercise than a necessary action occasioned by want. Satisfy his hunger and thirst and you annihilate the active principle of all his motions; and he will remain for days together in a state of stupid inaction.”3 For Buffon, Native American men were deficient mentally, sentimentally, and sexually because they had failed to exert authority over nature, their bodies, and the bodies of women in the ways that European men had.4

Few Americans read Buffon’s treatise, and even those who did may have rejected his claims, as future President Thomas Jefferson did in his Notes on the State of Virginia.5 Yet, Falconi’s automaton Indian translated Buffon’s naturalism into a material form that entertained urban citizens for over a decade. In making his automaton a warrior, the exhibitor reduced the humanity of his subject to the pursuit of food—one of the most fundamental of necessities—and the impulse to violence, the basest of the passions that reason and sensibility were supposed to cure in “civilized” men. In his advertisement, Falconi stressed the immediacy of the connection between order and behavior. Like a beast, Falconi’s Indian lacked the capacity for reason, morality, and self-control; it needed, as Buffon stressed, to be harnessed to the desires of civilized men and women.

Falconi’s automaton and Buffon’s theories came at a critical moment in the development of ideas about the relationship between machinery and human identity. Even before the codification of Isaac Newton’s laws of motion in 1687, philosophers and scientists had debated which human behaviors were governed by similarly inviolable laws. Traditionally, writers interested in human identity understood the self as existing on three distinct levels. At the base of the self were the thoroughly mechanical reflexes and processes that functioned without any conscious thought. Next were the animalistic passions that fueled violence and desires. At the pinnacle of the human self was the mind, the basis of morality and reason, which came from God and gave people a limited ability to control their passions. Everyone agreed that the reflexes were mechanical, but they differed on the degree to which the passions, reason, and morality mimicked machinery.6

When Falconi introduced his automaton, two strains of thought on these issues battled in Euro-American culture. In the strain prominent in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, human beings were completely and totally mechanical. Slaves to their reflexes, necessities, and passions, they lacked the willpower to act morally and rationally in society. Others in this mechanistic strain of thought—especially some Puritans and deists—believed that people possessed the capacity ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Introduction: An Intimate and Distant Machine

- Part 1 God and Demon, 1790–1910

- Part 2 Masters and Slaves, 1910–1945

- Part 3 Playfellow and Protector, 1945–2019

- Acknowledgments

- Notes

- Index