eBook - ePub

Future Remains

A Cabinet of Curiosities for the Anthropocene

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Future Remains

A Cabinet of Curiosities for the Anthropocene

About this book

What can a pesticide pump, a jar full of sand, or an old calico print tell us about the Anthropocene—the age of humans? Just as paleontologists look to fossil remains to infer past conditions of life on earth, so might past and present-day objects offer clues to intertwined human and natural histories that shape our planetary futures. In this era of aggressive hydrocarbon extraction, extreme weather, and severe economic disparity, how might certain objects make visible the uneven interplay of economic, material, and social forces that shape relationships among human and nonhuman beings?

Future Remains is a thoughtful and creative meditation on these questions. The fifteen objects gathered in this book resemble more the tarots of a fortuneteller than the archaeological finds of an expedition—they speak of planetary futures. Marco Armiero, Robert S. Emmett, and Gregg Mitman have assembled a cabinet of curiosities for the Anthropocene, bringing together a mix of lively essays, creatively chosen objects, and stunning photographs by acclaimed photographer Tim Flach. The result is a book that interrogates the origins, implications, and potential dangers of the Anthropocene and makes us wonder anew about what exactly human history is made of.

Future Remains is a thoughtful and creative meditation on these questions. The fifteen objects gathered in this book resemble more the tarots of a fortuneteller than the archaeological finds of an expedition—they speak of planetary futures. Marco Armiero, Robert S. Emmett, and Gregg Mitman have assembled a cabinet of curiosities for the Anthropocene, bringing together a mix of lively essays, creatively chosen objects, and stunning photographs by acclaimed photographer Tim Flach. The result is a book that interrogates the origins, implications, and potential dangers of the Anthropocene and makes us wonder anew about what exactly human history is made of.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Future Remains by Gregg Mitman, Marco Armiero, Robert Emmett, Gregg Mitman,Marco Armiero,Robert Emmett in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Biology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University of Chicago PressYear

2018Print ISBN

9780226508795, 9780226508658eBook ISBN

9780226508825Living and Dying

Huia Echoes

Julianne Lutz Warren

There is nothing for you to say. You must / Learn first to listen . . . / And, though you may not yet understand, to remember.

W. S. Merwin, “Learning a Dead Language” (2005)

the huia-trapper // whistles the song / I try to resist // I want to tug / something out of him // the radio voice says / believed to be extinct

Hinemoana Baker, “Huia, 1950s” (2004)

The Object

This chapter’s object—which embodies the Anthropocene—is an aural relic. This relic is the recording of a human imitation of extinct birdsong, which I am calling “Huia Echoes.” “Huia Echoes” is a dramatic chorus for our age, and beyond (plate 4).

Prelude: First Encounter

A few years ago, I was searching the audio archives of the Macaulay Library of the Cornell University Lab of Ornithology for recordings of living birds to accompany a talk on “Remembering Nature as Hope.” In the process, I incidentally came across the call of an ivory-billed woodpecker. I knew that this bird kind of the southeastern United States and Cuba was likely recently extinct. I caught my breath when I heard this vanished voice. My awareness roused, I made a list of the avian species listed as extinct by the “IUCN Red List of Threatened Species” and checked to see how many of these birds’ songs and calls had been saved in Macaulay’s collection. I discovered that of 140 extinct species, the voices of only 5 were represented. Hearing each one evoked poignant feelings. Catalogue number 16209 titled “Human Imitation of Huia”—a mid-twentieth-century soundtrack of a now-deceased Māori man mimicking songs of already extinct huia, a bird endemic to Aotearoa New Zealand—in particular, haunted me.

I could not forget these dead voices, living on.

May we never forget.

Perhaps more of us, following poet Merwin’s advice to “Learn first to listen”—to this bonded group of singing remains—will also remember and come to deeper hearing. Perhaps, in hearing, as Baker in her poem writes, though we may “try to resist // . . . to tug / something out” of the multiplex voice, we will learn that something from within ourselves is wanted to help enrich and multiply the whistling echoes.

The Historic Score: “Human Imitation of Huia”

The recording in Macaulay Library titled “Human Imitation of Huia” includes narration by Robert Anthony Leighton Bately, a man of British stock, descended from pioneer families. He explains that what we are hearing is a Māori man named Hēnare Hāmana—a bird mimic who in his younger days had heard living huia—whistling his re-creation, after they were extinct, of a sonic scene. In this imagined plot, a male and a female bird carry on a dialogue as they feed together in a forest. Here is that historic recording with Bately’s narration:

Audio 1: Listen to “Human Imitation of Huia”: http://macaulaylibrary.org/audio/16209.

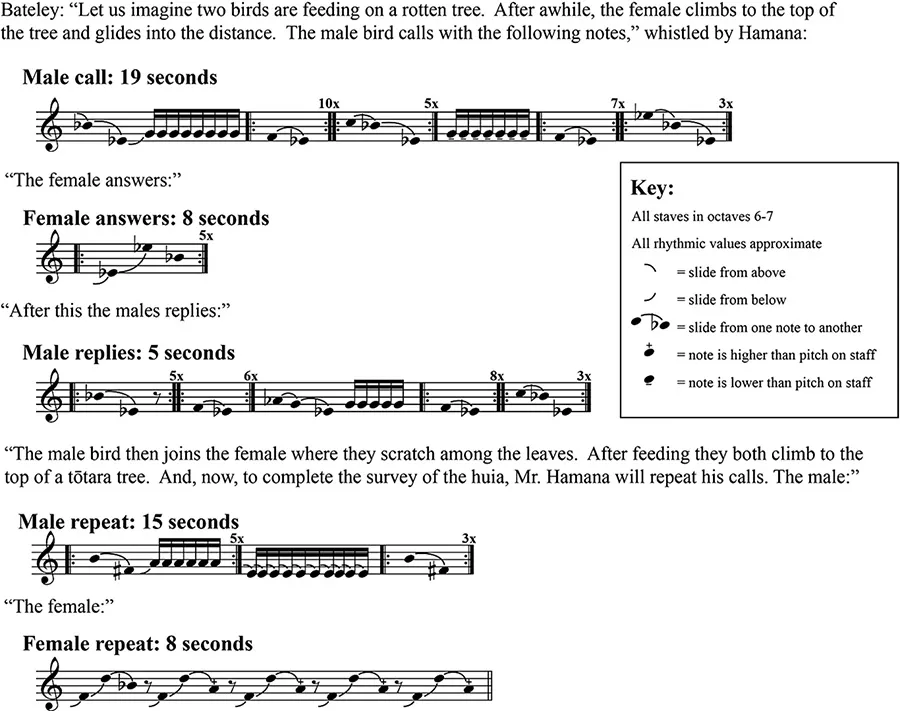

Figure 3 is the recording transcribed as a score.

Figure 3. Transcribed musical notation of whistled version of Huia songs with accompanying narration found in Human Imitation of Huia, catalogue number 16209 recording, Macaulay Library, Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Courtesy of Martin Hatch.

Presenting the Object: “Huia Echoes,” A Dramatic Chorus

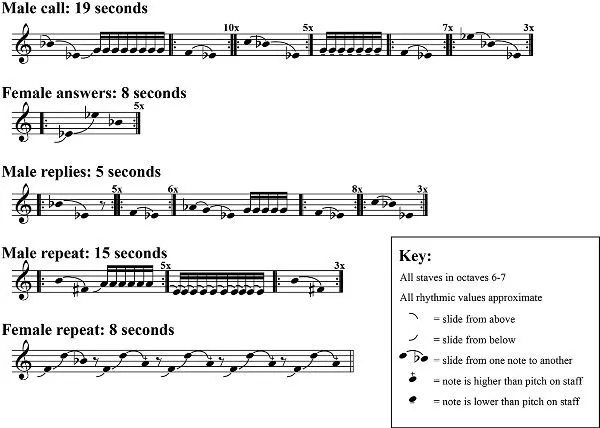

The narration helps sketch the story behind the imitated birdsong in the original recording. It was the whistle that charmed me, though. So, with the generous help of technicians, we removed the narration, freeing only the song to replay (see fig. 4).1 The intention of the descriptive words along with the human memory of a native bird tongue still shape the grammar of the musical phrases as the dramatic chorus resounds.

Figure 4. Transcribed musical notation of whistled version of Huia song extracted from Human Imitation of Huia, catalogue number 16209 recording, Macaulay Library, Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Courtesy of Martin Hatch.

Audio 2: Listen to “Huia Echoes,” a song of the Anthropocene: http://www.nzbirdsonline.org.nz/sites/all/files/27%20-%20Huia%20%28Imitation%29.mp3.

This, then, is the aural relic I am calling “Huia Echoes”—the chorus of extinct birdsong, echoed by human voice, echoed by machine, which may be played repeatedly—beginning, middle, end, beginning—looping into listeners’ heads, potentially echoing on.

“Huia Echoes”: Biographical Notes

Brief History of Huia, the Echoes’ Source—Of all the lands of this vast earth, huia, a unique wattlebird, inhabited mainly the northernmost of a pair of stormy southern islands that rifted from Gondwana 80 million years ago. Huia ancestors may have flown here from Australia on westerlies across the sea 50 million years later. The islands’ first human beings, the Māori ancestors, finally appeared just 800 years ago. The name they gave the birds sounds like their song—huia. And the birds’ place, also the people’s new home, they called Aotearoa, or, in English, “long white cloud.” Later, European colonists, whom Māori named Pākehā, christened the islands New Zealand. The bird, in Latin, became known as Heteralocha acutirostris, which in English means something like “the husband’s is different from his wife’s piercing sharp beak.”

Huias’ best-known calls have been described as a flute-like whistle with a prolonged note followed by short, quickly repeated ones, and as a recurring legato phrase quivering at the end. The birds’ songs issued from their ivory bills, which were sexually dimorphic to an unusual degree. Females’ bills were lancing-long and gracefully curving. Those of males were short and sharp like pick-axes. A pair of orange wattles, fleshy pendants ornamenting the gape flanges of both sexes, contrasted brightly with feathers that were silky blue-black from head to tail. The tips of a huia’s twelve tail feathers, however, like his or her bill, were the color of ivory.

In the early decades of the twentieth century, huia joined a long line of these islands’ birds—a quarter of them, or over fifty species—who have become extinct since the first human contact in the thirteenth century. More than half of these species, including every kind of moa, vanished between the time of Māori and eighteenth-century European arrivals. The rest were rapidly lost after Pākehā came. And, currently, many more species—including huias’ closest relatives, saddleback (tieke or Philesturnus carunculatus) and North and South Island kōkako (Callaeas wilsoni and C. cinerea)—are on life’s brink.

The loss of huia, extinct by the early twentieth century, can be blamed on a constellation of place-specific, human-initiated causes that today also ring, repeatedly, with global familiarity. Causes involved acute and chronic disruptions of long-evolved interdependencies among minerals, soils, waters, plants, animals, and air. At the time of Māori ancestral canoe arrivals, the islands’ only mammals were bats. These first people brought with them bird-hungry Pacific rats. Then, a few hundred years later, European ships delivered more mammalian predators, like Norway rats, cats, stoats, and ferrets. Red deer from Scotland ate regenerating forest; and exotic birds, such as minas from India, brought unfamiliar ticks that stressed local birds.

Humans also dispatched huia directly. Traditionally, Māori hunters snared them for their beautiful tail feathers used for chiefly and sacred purposes. With the firepower of guns and the commodification of their feathers as hat ornaments (particularly after the future King George V donned one), and as parlor curiosities and museum specimens, Pākehā and Māori hunting intensified. From the nineteenth century, intense Pākehā-driven alterations of land and water also expanded. The new-come imperialists bought or appropriated wide swaths of forests and swamps, many of which were huia and Māori whenua or ancestral places, supporting and supported by interwoven avian-human indigenous identities. The newcomers burned, timbered, and drained these places and divided long-standing relationships in exchange for a managed system familiar to them— one of grass pastures, sheep and cows, and crops of potatoes, oats, and wheat, mined minerals and fossil hydrocarbons, railways and towns of well-warmed houses with weeded gardens, Chinese cherry trees, roads, shops and banks, stone cathedrals, museums, radio stations and recording machines.

Echo 1, Human Voice: Curious huia could be lured near to a practiced imitator whistling a resemblance to their songs. As a young man, Hāmana (b. 1880; d. >1949)2—a member of Te Aitanga-a-Māhaki, Ngāti Porou, known in Bately’s words as “a local Māori experienced in giving huia calls”—assisted in at least two Pākehā-led huia search expeditions in 1908 and/or 1909. Only one bird was encountered on the earlier expedition through formerly prime habitat in the northern portion of the Ruahine Range of the North Island.

Huia had occupied wet mountain forests with arching tree branches of wide-girthed tōtara with gold-flaking bark, rendered by Pākehā artists as cathedral-like, and stands of southern beeches floored with decaying boles stocked with huhu grubs and hinau trees with tasty purple berries, both of which huia and Māori liked to eat. Huia frequented tangled manuka groves teeming with tree-crickets, another bird delicacy, on grounds sloping into brook-fed ravines of towering crimson-flowered rewarewa and pukapuka shrubs fragrant with cream-colored blooms. In the soundtrack, now as an aging man, Hāmana echoes a pair of remembered huia voices, whose kind no one will ever hear again in the flesh, singing to each other in an area of their former forest.

Echo 2, Machine Recording: The Pākehā habit of collecting skins of birds known to be endangered to save some museum knowledge of them, or to keep as cabinet curiosities, perhaps extending even to takings for keepsakes of Māori tradition, paradoxically, reduced avian numbers already in perilous decline. Recording equipment, on the other hand, could multiply rather than deplete stocks of avian songs, but was not readily available before huia were gone.

By 1949 the city of Wellington had a radio station with recording facilities. Understanding the bird to be an “object of unusual interest,” Bately, as a local historian and author, wanted “to preserve a resemblance to the call of the huia . . . which is believed extinct.” So Bately invited Hāmana, who, like him, lived in Moawhango near Taihape, to travel together about 140 miles south to station 2YA’s (now RNZ National) studio.

There, prompted by Bately, Hāmana whistled his recollection of huia calls into a microphone. Technical experts used a recording lathe to etch the composite music of native bird tones and Māori echo, plus Pākehā narration, into a spiral of grooves on a black lacquer disc, which, as it spun in contact with a needle, could be played back. This machine sounding, then, is a second echo that not only reproduced a remnant of the extinct birdsong, but also saved human memories of huias’ phrases, along with the thus-obscured cultural tradition of learning them. All of these losses were given a voice.

Echo 3 and Echoing On, Song-repeating Listeners: The bird-man-machine soundings thereafter circulated and multiplied into countless other echoes, in reproduction of the recording sung out by turntables and by newer kinds of playback machines, and, by some listeners, even embodied and rehummed into the living world. Soon after the Wellington recording was made, the dramatic soundtrack was presented as part of a talk on “Native Birds of Our District” by V. Smith of Taihape to the Royal Forest and Bird Protection Society, which appears to have held the phonograph record. Later, the original ten-inch acetate disk was copied onto tapes, including by the New Zealand Broadcasting Corporation. John Kendrick, a New Zealand conservationist, sound recordist, and radio host of “Morning Report bird calls,” took a copy of their tape. This copy was copied by field collaborator William V. Ward for the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. The lab labeled the recording as catalog number 16209 in their Library of Natural Sounds, now the Macaulay Library. Macaulay began digitizing in 2000, subsequently making their holdings available to echo on with a quick click through the Internet. This, as I’ve explained, is how I first encountered “Human Imitation of Huia,” which became edited into this chapter’s focal object—a sonic artifact, which I am calling “Huia Echoes.”

Spinning “Huia Echoes”

There is “a way the older people have of telling a story,” Māori author Patricia Grace says, “a way where the beginning is not the beginning, the end is not the end. It starts from the center and moves away from there in such widening circles that you don’t know how you will finally arrive at a point of understanding, which becomes itself another core, a new centre” (Thompson 2008, 66).

Perhaps “Huia Echoes” is telling this sort of story, starting at the core of a once-feathered source of destroyed-forest birdsong, circling out in a formerly-forest-bird-interwoven-man’s voice, recorded by a descendant of colonist pioneers into the grooves of a spinning disc, then copied into other machines to repeat into air, potentially resounding through unknown ears and recurring in others’ tongues elsewhere.

This choral artifact as a whole, then, might enchant our imaginations into another central starting place that begins with listening to “Huia Echoes” as a different kind of being. Indeed, this compound voice, I have come to feel, unexpectedly, is not an object after all. The extinct music somehow is not dead. Latent within technology, “Huia Echoes” is an alive companion, evident when I switch on a machine. Indeed, keeping near, housed in my iPhone, this musical story-teller by encouraging me to hear others helps me feel less alone.

Flowing through a legacy of saved memories—elemental, biotic, and mechanical—through a small speaker, the birdsong traces replay into different places. I begin to understand the mimicked dead birdsong as a de-feathered, skin-less teacher, an audible silence—a reverberating absence—bringing forward the past in moving conversation with the present.

For example, listening in boreal Alaska’s Atigun Pass, I hear the colonist’s machine-bound avian and human prisoners absorbed into wind sounding on rocks, water, and tundra leaves. I want to shout “Quiet!” to the play of air. But, keeping myself still, I also wish the currents to rush on in their forgetting way, dissipating cruelties to each unique winged-body and dark-skinned person who has suffered them. An inkling blows in from behind, whispering: we belong to each other.

As I listen in the foggy pillared peaks of Wulingyuan Scenic Area of China’s Hunan Province, “Huia Echoes” pushes through a din of human-crowd voices so effectively that the whistle draws curious and also nervous looks. As do I, with my blue eyes and pale skin. My first impulses want me and my singing friend to hush or blend in alongside a contrary one to defend us both in a very loud voice, followed by an urge to announce my history of oppressing failures—personal and ancestral—to act with such spirited care toward all manner of life, accompanied by a humiliating feeling that this in itself can be self-aggrandizing. An insight rises from within, humming: desire healing.

It is this legacy of failure—institutionalized—that has delivered the world-of-life into a global epoch of dire consequences, still unfolding—many of which, despite anyone’s deepest desire otherwise—can never be unmade, like huia’s extinction—an entire bird language—extinguishing entwined Maori sacred tradition. This is the epoch that some have dubbed the Anthropocene, which might be considered yet another starting point for a fresh round of storytelling.

Anthropocene Remains

The Anthropocene, in albeit contested geological terms, is characterized by marks of worldwide human domination in fossil and chemical changes in soils, sediment, ice, or rock. In cultural terms this is an epoch of evidence-based perceptions of rippling, unintended outcomes of human actions reversing billions of years old trends of generative Earth. Reverses include unprecedentedly rapid rates of extinction—careening, in a matter of centuries, toward the likelihood of over 75 percent of bird species missing plus a similar proportion of other living types—with soil fertility diminishing faster than building up interpenetrating with global climate change, rippling in other forms ruin, unjustly distributed.

Injustices might not...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Preface

- The Anthropocene: The Promise and Pitfalls of an Epochal Idea

- Hubris

- Living and Dying

- Laboring

- Making

- Contributors

- Color Gallery