- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Black Studies, Rap, and the Academy

About this book

In this explosive book, Houston Baker takes stock of the current state of Black Studies in the university and outlines its responsibilities to the newest form of black urban expression—rap. A frank, polemical essay, Black Studies, Rap, and the Academy is an uninhibited defense of Black Studies and an extended commentary on the importance of rap. Written in the midst of the political correctness wars and in the aftermath of the Los Angeles riots, Baker's meditation on the academy and black urban expression has generated much controversy and comment from both ends of the political spectrum.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Black Studies, Rap, and the Academy by Houston A. Baker, Jr. in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Histoire & Histoire de l'Amérique du Nord. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

BLACK STUDIES: A NEW STORY

The single task that I set myself for the summer of 1991 was an essay on Black Studies and the institution of English. I was less certain about English in its daily, postmodern unfoldings than I was about Black Studies, for who can ever be certain what is happening at Duke? By contrast, everyone knows the familiar story of Black Studies. It is a narrative of Hagar’s children redeemed from exile by the grace of affirmative action and the intentionality of Black Power. It is a vernacular tale, resonant with rhythm and blues. And it has been relegated in recent years to the briefest imaginable space in the encyclopedia of postmodern American academics. Thus it was that, in the summer of 1991, I wanted to construct a Black Studies account that would produce, perhaps, a conclusion rather different from “Negroes also spoke.” I hoped, in short, to avoid “soul” narration.

A number of factors converged, however, to make my job more complicated than I had envisioned. First, the currents of the PC (Political Correctness) Cavaliers were swirling, during the summer of 1991, with the energy of Edgar Allan Poe’s maelstrom. Everywhere one turned, after the Modern Language Association opposed the nomination of Carol Iannone to the National Council on the Humanities, there were editorials and “op. ed.” meditations denouncing a new “leftism” of “tenured radicals” in the American academy. Professors who suggested that Alice Walker might conceivably form part of a course devoted to American literature were held to be equivalent—in the bizarre logic of the PC Cavaliers—to Ku Klux Klanspersons. (Don’t ask me to explain it.) And in the economies of the PC Cavaliers, Black Studies was just one more roundheaded carryover from the chaotic 1960s, when mere anarchy was loosed in halls of ivy. Like other interdisciplinary area studies (e.g., Women’s Studies) to which it lent force, Black Studies was suddenly being held accountable for a new “McCarthyism.” (Again, don’t ask me to explain it—at least not yet.)

There thus seemed to be at least two incumbencies if I were going to achieve a new and different story. I would certainly have to account for the new politics of PC by, at least, re-vocabularizing the familiar Black Studies tale to avoid its easy imbrication in a simpleminded, right-wing rhetoric of denunciation. Second, since Black Studies was founded as a social, scholarly, and pedagogical enterprise to deal with black culture, I would have to account for the relationship of such studies to black urban culture. Black urban culture, I believe, provided much of the impetus for Black Studies’s founding, and surely in our own era, it is the locus of quite extraordinary transnational creative energy.

Having arrived at the contours of my narrative mission, I had absolutely no clear idea of how to fulfill it. I felt like Mr. Phelps in the original run of Mission Impossible: I was out “in the cold,” and the scholarly muses had disavowed knowledge of my proper person. In such instances, there is no recourse but improvisation. So I found myself by midsummer trying to follow the unfolding PC debates, struggling to read cultural studies materials, and carving out time to catch up on the black urban expressivity of Yo! MTV Raps. This welter of anxiety and influences produced such hybrid moments as putting aside the Wall Street Journal’s latest diatribe against PC to take up the writings of Paul Gilroy while listening, with one ear, to the jamming lyrics of Ice-T’s unbelievable 0G (Original Gangster) album. Having concluded that the notion of “nation,” as employed and analyzed by Black British cultural studies, was indispensable to my narrative, I set out on a sunny Sunday in August to borrow a copy of Benedict Anderson’s Imagined Communities from a friend who lives near Philadelphia’s Benjamin Franklin Parkway. Instead of Anderson’s book, I quite serendipitously discovered an energetically imagined community of interests in action, one that seemed rather like a Wordsworthian spot of time.

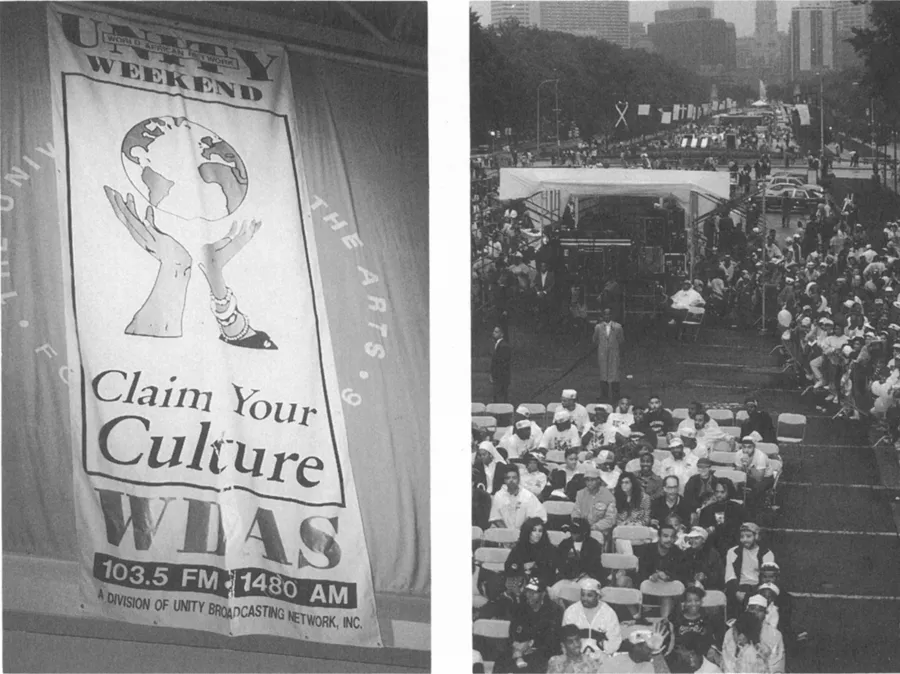

It was Unity Day on the Parkway. Thousands of people were assembled, and the scene seemed to offer—in its collaged multiplicity of sound and image—a foreshadowing of both the form and substance I hoped to capture in my new story of Black Studies. But I knew immediately that no written text could fully capture the gorgeously arrayed young black people in African-print shirts and dresses set off by roped-gold jewelry and kofi hats. Nor could academic writing make readers feel the heat and stillness as I approached what I shall call the “surveillance” or, alternatively, the “discipline and punish” tent set at the very head of the Benjamin Franklin Parkway. This tent (of which I shall have more to say later) was the largest of the Unity Day tents; it was the first among all competitors of the day’s interiors. It was the Dantesque first darkness, blocking the view (but not, of course, the sound) of stages from which the music flowed.

Unity Weekend 1992. Photographs courtesy WDAS Radio, Philadelphia.

The brightness and energy, in combination with the celebratory rhythm and beat of Unity Day, proved as inspirational for me as a “filament of platinum” among alloying elements. The beauty, complexity, and expressivity of the Blackness at work on the Unity Day Sunday afternoon were sufficient to convince even an overly influenced and anxious me that there was a new and important array of energies at work in the world that had to be accounted for in any story yet to be told of Black Studies. Like the innovative cultural workers whom I discovered on the parkway that August afternoon, I realized that I would have to take what I had at hand and, even under the astute surveillance and policing of the present day, convert it into a multirhythmic and different story of both academic and general social processes that have marked the past twenty-five years. I decided the term moral panic, from cultural studies, would nicely serve my ends. It gestured before and after, as it were, serving a useful analytical purpose with respect to both the first arrival of black urban migrants at the gates of the academy and to the belated current outcry against that arrival—Political Correctness. Less modishly, and drawing from the “normal practice” of academic scholarship, I realized that there was no theoretical or cultural-studies escape from history. And so the story unfolds.

The new story that unfolds is a drama of shifting horizons, contested spaces, and simulacra. If one recalls the now defunct television show College Bowl (which was every thinking man’s honorable pastime on Sundays during the early sixties), the image of the American university evoked is a pastoral landscape dotted with spacious buildings, well-dressed white youth smiling and chatting, and studious tweed-jacketed professors earnestly discoursing before rapt audiences. This image of a harmonious garden of knowledge overseen by sober white intellectuals was always shown in brief film clips at half-time for each of the competing College Bowl teams matched in rapid-fire responses to “common curriculum” questions of Western Civilization: for example, “What eighteenth-century British economist first announced the iron law of wages?” Usually the participants were young white males displaying a talent for “classical” learning that precious few Americans would ever need to know. College Bowl’s pastoral image had become standard fare during the silent American 1950s, and it was not merely a product of smoke-and-mirrors. It carried, in fact, the specific weight of the American academy’s founding. For even in the variousness of its founding, the American university was always conceived as a quiet, scenic space of disinterested thought—a territory functionally and strategically removed from everyday life. It is not accidental that seventeenth-century Harvard was called the “seminary in the wilderness.”

Without belaboring the point, it seems almost an understatement to say that the American academy is a direct, shaped product of founding ideologies. Sectarian colleges received their marching orders and general character from their respective ministerial governing boards. Private institutions marched to the beat of trustees like Ralph Ellison’s Mr. Norton, a manicured obsessive-compulsive from declining New England stock, from the novel Invisible Man. The agendas and protocols of state colleges and universities were dictated by legislatures of their home territories. Their life and work were overdetermined by imperatives of the Morrill Acts.

Without ideologies is no American university, to paraphrase Blake, who felt that without “contraries is no progression.” Certainly the actual existence and control of American colleges and universities was contrary to their advertised “disinterestedness.” John Henry Newman and Matthew Arnold alike knew that it was not disinterestedness that was to be sought in the nineteenth-century British university, but, rather, escape—from the messy, modern realignments of race, class, nationality, and knowledge formation that had become far more “public” and “general” by midcentury than either Newman or Arnold cared for.

Until the emergence in mid-twentieth-century America of what Clark Kerr called the “multiversity,” United States’s campuses were relatively simple and sometimes indisputably pastoral gardens of Western knowledge indoctrination, conditioned always by strong and discernible ideologies. With the coming of the multiversity, these ideological interests increased in scale as big business and big government poured billions of research dollars into the academic garden, transforming it into a factory. What did not change, of course, were the fundamental whiteness and harmonious Westernness of higher education. Even when tweed-jacketed white men were no longer in front of rapt audiences but hermetically bent on highly financed “research,” they were still white men. Likewise, the student body—even if it was no longer lolling in tree-shaded gardens—was still, almost to a young man or woman, “white, white, white,” as they say repetitively for emphasis in most creoles of the world.

Of course, I am aware that there are exceptions to this characterization of Western knowledge production. American universities have always been marked by occasional sites of resistance. And on the whole one would be hard-pressed to discover the degree of expressive freedom enjoyed by the university in any other American institution. Moreover, Nathan Huggins has pointed out in Afro-American Studies, a report compiled for the Ford Foundation, that after World War II, American universities became more democratic as their enrollments soared, bringing non-middle-class students and returning GIs to campuses. Catching a general impulse to reform, universities expanded their mission to include remedial education and the preparation of traditionally excluded citizens for upward class mobility. Even with such changes, however, the exclusivity of America’s well-financed and traditionally all-white sites of higher learning remained a matter of policy and record. As the popular philosopher Pogo said in 1963, “Outside pressure [on the American academy] creates an inside pressure: academic conformity. The average [American] professor is no Socrates.” Thus, in 1963 the American university was a very quiet, decorous, white project.

My own experiences certainly accord with Pogo’s terse depiction of the American academy—I can almost feel, even as I write this sentence, the hushed decorum of the University of California at Los Angeles when I arrived for graduate study in 1965. Eucalyptus and palms shaded wide boulevards and intimate walkways. Quaint outdoor “Gypsy Wagons” supplied orderly dining places for a seemingly endless array of white people. I was thrown into black culture shock by Westwood Village, where even menial jobs were occupied by Mexican Americans, not bodacious brothers and sisters. And when I tried my undergraduate Howard University jive and juju on one of the very few Negro freshmen, greeting him with “What’s happening, brother?” he replied, “Why . . . uh . . . good morning. How are you?” His eyes almost bugged from his head in haute bourgeois panic. Yes, even though UCLA was indisputably enveloped in the long shadow of the 1965 Watts summer rebellion, the campus maintained a signally quiet grace under national pressure for black liberation. But everything was soon to undergo a change that might have made even Negro freshmen blanch in 1965.

In the midsixties, the quiet of the American university—whether garden or factory—was shattered forever by the thundering “NO” to all prior arrangements of higher education in America issued by the Free Speech Movement (FSM). Witness those erstwhile docile (or robotic) young white men and women of College Bowl transformed into revolutionary cadres questioning the prerogatives of faculty and administrators. Firebrands demanding curriculum revision, deconstructing the rhetoric of American higher education in toto. Witness such rebellion spreading like wildfire across campuses everywhere. What an incongruous moment! Stupefied administrators, faculty, trustees, men and women of the cloth, and bewildered legislators wondered what dread “outside” demon had infected the halls of ivy. For by the midsixties it was obvious to everyone concerned that an outside “social” ambiance and an inside “academic” atmosphere had converged like giant weather fronts. And no one needed a meteorologist to know that a hard rain was gonna fall.

The silencing academic walls were socially breached at midcentury by codes, strategies, and cadences of the black liberation struggle in America. If W. E. B. Du-Bois speaks persuasively in The Souls of Black Folk about a coming of black folk to college that produced new and joyful songs of Talented Tenth enlightenment, surely we can speak today of the emergence on American campuses of strident white students who felt the wind-blown lyrics of a black American liberation spirit moving in their souls. Many of these students had participated in direct nonviolent protests for Civil Rights in their home states; others had made their way to Mississippi during the Freedom Summer of 1964. They were primed for protest, and it is fair to say that the FSM transformed the image of the American university from a College Bowl still life into a rollicking video of transgenerational conflict. The country witnessed and responded in deeply condemnatory tones.

The University was transformed, in fact, into a metonym for social chaos. If “mere anarchy” was loosed on America, virtually everyone agreed that the bonds of law and order had been severed by students. “Blame but the students!” became the rallying cry of agreement.

Now the social disorder of the United States was in reality a product of ill-conceived military adventurism in Southeast Asia and a monstrously excessive federal egotism on the home front. The attribution of responsibility for chaos to the university amounted, therefore, to a metaphorical repositioning, a displacement of responsibility that sought to withdraw attention from both American imperialism abroad and vicious United States reactions to black demands for civil rights at home. The voting citizenry of the U.S. decided that it was far more profitable and comforting to scapegoat the university than to assess the criminality of career politicians and their henchmen and constituents at home and abroad.

And it is here that Black Studies as a floating signifier becomes a powerful analytical tool. For the convergence of Civil Rights and the FSM did indeed produce incongruity. It was only the further development of this convergence, however, in the form of Black Student Immigration that gave resonance to a revolutionary hybridity on American campuses. For with this immigration, “inside” and “outside” came into brilliant kaleidoscopic allegiance.

Black student recruitment; black student scholarships and fellowships; black dormitories, student leagues and unions; black faculty recruitment and curriculum revision; and preeminently Black Studies all became signs of new times and territories in the United States academy. Black Studies became a sign of conjuncture that not only foregrounded the university as a space of territorial contest, but also metaphor...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Copyright

- Title Page

- Series Page

- Dedication

- Epigraph

- Contents

- Preface

- 1. Black Studies: A New Story

- 2. The Black Urban Beat: Rap and the Law

- 3. Expert Witnesses and the Case of Rap

- 4. Hybridity, Rap, and Pedagogy for the 1990s: A Black Studies Sounding of Form

- Afterword

- Index