eBook - ePub

Between the Black Box and the White Cube

Expanded Cinema and Postwar Art

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Today, the moving image is ubiquitous in global contemporary art. The first book to tell the story of the postwar expanded cinema that inspired this omnipresence, Between the Black Box and the White Cube travels back to the 1950s and 1960s, when the rise of television caused movie theaters to lose their monopoly over the moving image, leading cinema to be installed directly alongside other forms of modern art.

Explaining that the postwar expanded cinema was a response to both developments, Andrew V. Uroskie argues that, rather than a formal or technological innovation, the key change for artists involved a displacement of the moving image from the familiarity of the cinematic theater to original spaces and contexts. He shows how newly available, inexpensive film and video technology enabled artists such as Nam June Paik, Robert Whitman, Stan VanDerBeek, Robert Breer, and especially Andy Warhol to become filmmakers. Through their efforts to explore a fresh way of experiencing the moving image, these artists sought to reimagine the nature and possibilities of art in a post-cinematic age and helped to develop a novel space between the "black box" of the movie theater and the "white cube" of the art gallery. Packed with over one hundred illustrations, Between the Black Box and the White Cube is a compelling look at a seminal moment in the cultural life of the moving image and its emergence in contemporary art.

Explaining that the postwar expanded cinema was a response to both developments, Andrew V. Uroskie argues that, rather than a formal or technological innovation, the key change for artists involved a displacement of the moving image from the familiarity of the cinematic theater to original spaces and contexts. He shows how newly available, inexpensive film and video technology enabled artists such as Nam June Paik, Robert Whitman, Stan VanDerBeek, Robert Breer, and especially Andy Warhol to become filmmakers. Through their efforts to explore a fresh way of experiencing the moving image, these artists sought to reimagine the nature and possibilities of art in a post-cinematic age and helped to develop a novel space between the "black box" of the movie theater and the "white cube" of the art gallery. Packed with over one hundred illustrations, Between the Black Box and the White Cube is a compelling look at a seminal moment in the cultural life of the moving image and its emergence in contemporary art.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1: RHETORICS OF EXPANSION

You know, this 3-D process isn’t all that glamorous or new or exciting.

ANDY WARHOL

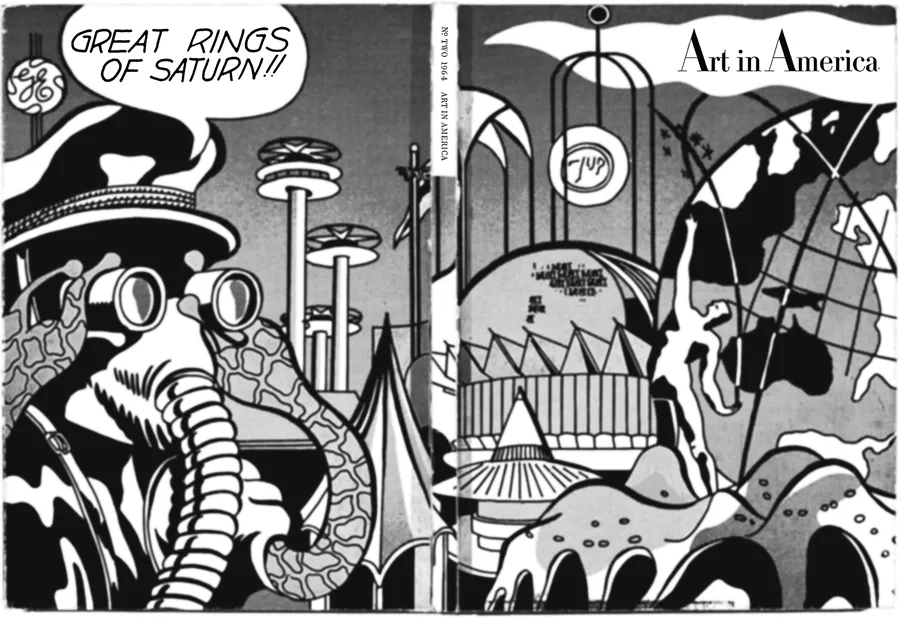

Figure 1.1. Roy Lichtenstein, New York World’s Fair, cover illustration for Art in America, April 1964. © Estate of Roy Lichtenstein.

Multiscreen Cinema and the ’64 World’s Fair

In April 1964, the World’s Fair came to New York. Reports of nightmarishly congested parking and two-hour-long exhibit lines were unable to dissuade millions of visitors from all over the world. Many locals attended the fair not once or twice but literally dozens of times during the two summers it was open.1 Yet if the success of previous World’s Fairs had rested on their ability to inhabit a futural temporality—to offer viewers spectacular yet convincing dreamworlds of tomorrow—the New York World’s Fair managed to botch the job entirely. Despite its resolutely “space-age” theme, it was widely criticized as being neither forward-looking nor visionary. Largely planned and designed in the late 1950s, by the mid-1960s it had become a kind of living relic, a ready-made ruin. As America and the world had changed drastically, the fair seemed frozen in time. Rather than familiarizing viewers with a strange and exciting future yet to come, it managed to defamiliarize that which had seemed natural only a few years back.

On the same site a quarter century before, the 1939 World’s Fair had been received with both popular and critical acclaim. General Motors’ Futurama exhibit was a heady vision of the future metropolis featuring towering skyscrapers, elevated multilane highways, and cars for everyone. Coming at the end of the Great Depression, when many families didn’t yet own cars and superhighways were cultural novelties, Futurama inspired millions. Yet for the baby-boomer generation coming of age in 1964, burgeoning suburbs and extended workaday commutes were beginning to provoke a reconsideration of the automotive romance. General Motors doubled down. Its updated Futurama II showcased a robotic “Jungle Road Builder” intended to delve deep into the last untrammeled jungles of the world, eviscerate everything in its path, and leave behind elevated asphalt superhighways. For the nascent youth culture of the 1960s, these kinds of technologies were a proverbial “road to nowhere”—a vision of the future better left in the past.

What did seem particularly new and exciting was the spectacular range of multiscreen cinema that was there on display. Man in the 5th Dimension at the Billy Graham’s Christian Evangelical Association Pavilion, Saul Bass’s The Searching Eye at the Kodak Pavilion, American Journey at the US Pavilion, The Triumph of Man—“an immersive panoramic journey through the ages”—at the Travelers Insurance Pavilion, To the Moon and Beyond at the Transportation and Travel Pavilion, and Charles and Ray Eames’s Think at the IBM Pavilion were among the most popular exhibits of the fair. To Be Alive!, produced by Alexander Hammid and Francis Thompson for the Johnson Wax Pavillion, was perhaps the most popular and celebrated of them all. Hammid was principally known for his collaboration with Maya Deren on Meshes of the Afternoon twenty years before, and Thompson for his prismatic city symphony NY, NY of 1957. Their collaboration on To Be Alive! proved quite unlike these earlier works. A program presented the short film’s message: “While millions of people are frustrated in this complex modern world of ours, there are millions of others who retain a sense of the underlying wonder of the world, who have a capacity for finding delight in normal, everyday experience, and who realize that there can be great joy in simply being alive!”2

While the fair would be roundly criticized for its aesthetic conservatism, Thompson and Hammid’s panoramic triple-screen film was an instant standout. Combining images from Africa, Italy, and the United States, To Be Alive! was like an abridged, cinematic version of Edward Steichen’s The Family of Man from the decade before, and it was similarly well received. According to the company magazine, “more than 300 members of the New York press corps gave the film a standing ovation” after the advance screening, and played to “capacity audiences every day of the fair.”3 Viewers were forced to wait “as long as two hours” to see the eighteen-minute film, and attendance over the twelve months of the fair reached more than five million within its single theater. “Tremendous success brought inquiries and requests to see the film from throughout the world. Celebrities came almost every day until our guest register read like an international Who’s Who of entertainment, business and government leaders.”4 As with The Family of Man, the frenzied pitch of excitement was in no small part due to the particular conjunction of an innovative aesthetic form with a clear and uplifting social message.

To Be Alive! received a number of honors, including the 1965 Academy Award for Best Short Subject Documentary. More intriguingly, the film would also take pride of place within a special issue of the underground journal Film Culture devoted to expanded cinema the following year. “To Be Alive! and the Multi-Screen Film” began with the breathless declaration that now that To Be Alive! had been given an Academy Award, the multiscreen film, “once a freak of the film world . . . was recognized as a new and effective motion picture form by the Industry.”5 One might reasonably ask why a publication devoted to experimental and avant-garde film would concern itself with what the industry considered “effective,” but this declaration exemplifies the confusion surrounding the rhetoric of expanded cinema within the mainstream and alternative press. While the term often implied a broad range of activities beyond the industrial norms of cinematic presentation, the most obvious and persistent of these activities, and therefore the one most quickly and powerfully associated with it, was the use of multiple projection. Yet the widespread excitement over multiscreen cinema as new technology and a new form of cinematic practice was possible only due to a particularly acute form of historical amnesia, because the multiscreen cinema that emerged in the 1960s was neither particularly novel nor greatly innovative. Rather, it was merely the latest iteration of a technology that had been invented and reinvented compulsively, and almost continuously, since the late nineteenth-century birth of cinema itself.

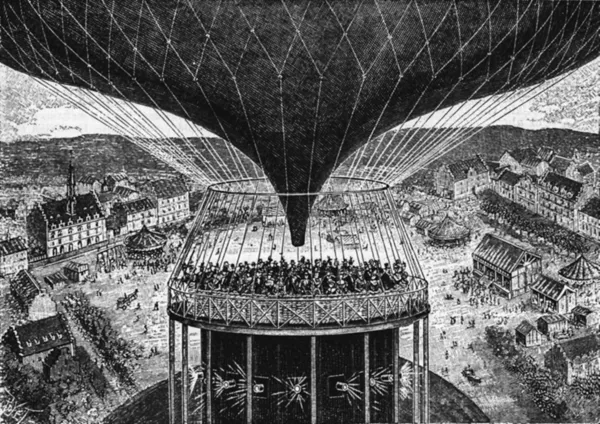

Figure 1.2. Raoul Grimoin-Sanson, illustration of Cinéorama at the 1900 Exposition Universelle in Paris. Scientific American, supplement, no. 1287, September 1, 1900. Interior of exhibition.

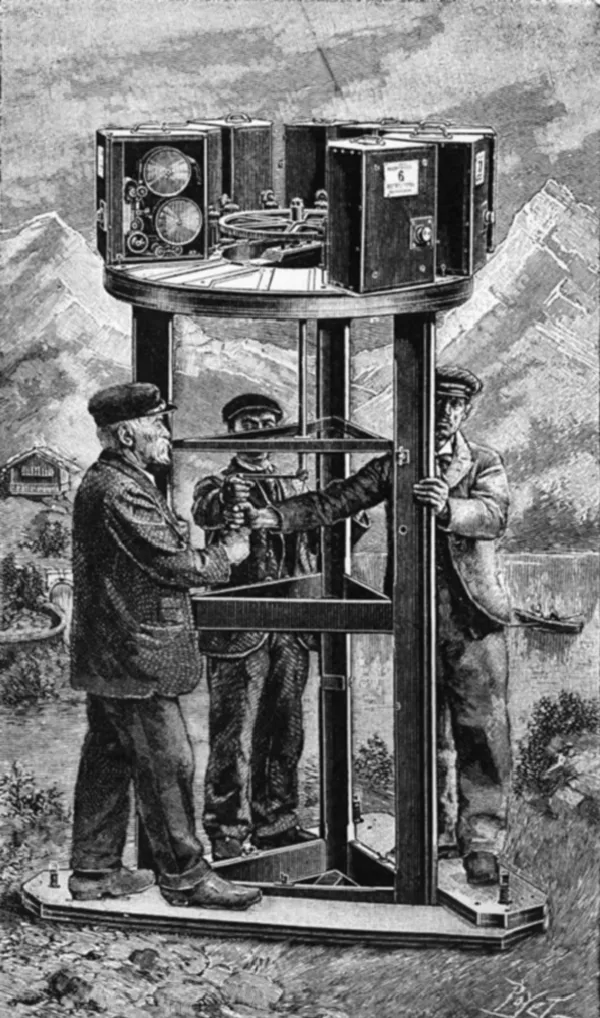

Figure 1.3. Raoul Grimoin-Sanson, illustration of Cinéorama at the 1900 Exhibition Universelle in Paris. Scientific American, Supplement, no. 1287, September 1, 1900. Multiple camera apparatus.

Well before the emergence of classical Hollywood, even before the most rudimentary grammar of industrial cinema, Raoul Grimoin-Sanson provided the template for the monumental, immersive cinematic spectacle with his Cinéorama of 1897. Conjoining the nineteenth-century fascination with panoramic painting and the newly invented technology of cinematographic projection, this ciné-panorama employed ten synchronized, radially facing movie cameras in a hot air balloon to capture its ascent over the city of Paris. For its debut at the Paris Exposition Universelle of 1900, spectators were situated within a similar basket while ten synchronized projectors, located beneath them, projected the film in a 360-degree panorama some one hundred meters in circumference. Despite its unqualified popular success, Grimoin-Sanson’s exhibit was prematurely shut down after being declared a fire hazard by the city police, and his company went bankrupt immediately thereafter. Its commercial failure would serve as a template for a range of beleaguered efforts over the next fifty years as a succession of artists and engineers again and again reinvented the ciné-panorama as a spectacle of overwhelming and immersive monumentality.6

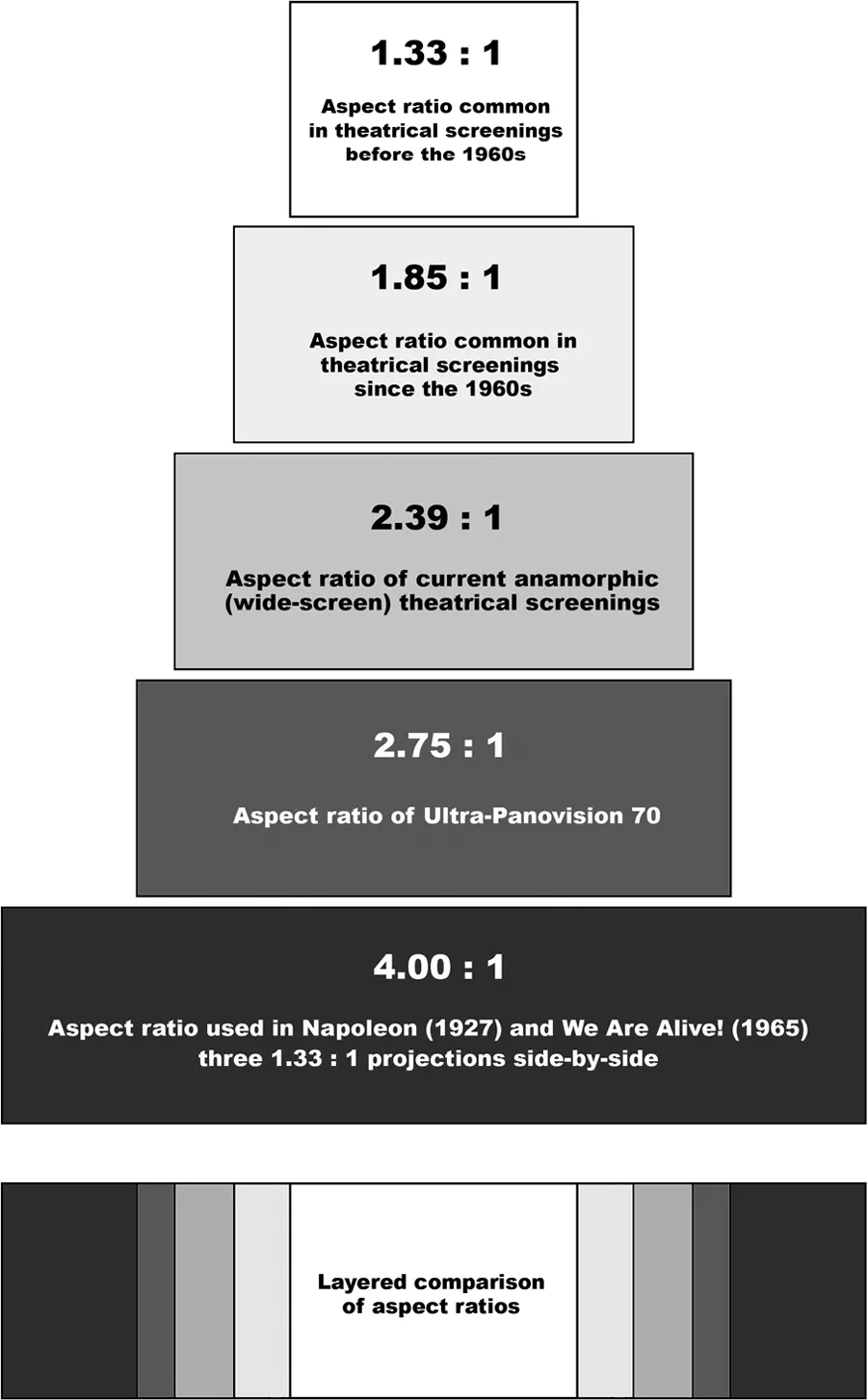

The most famous of these attempts within film’s silent era was undoubtedly Abel Gance’s “invention” of his three-screen Polyvision cinema for his 1927 feature Napoléon. And during a few brief climactic moments at the end of that film’s final reel, Gance would indeed use these three screens in a radical new way, presenting different images on each in a kind of simultaneous montage. Yet for most of the final reel, the multiple screens functioned just as they had for Grimoin-Sanson: augmenting the scale of the image with the creation of a single, continuous ciné-panorama. It was certainly this expanded scale, rather than any novel possibilities for juxtaposition, that captured the immediate attention of Hollywood. By the late 1920s, Fox was promoting its Grandeur process, Paramount its Natural Vision, and Warner Brothers its Vitascope—all expensive, large-format processes that magnified the size and quality of the cinematic image but failed spectacularly at the box office and were abandoned soon after their introduction.

After the Great Depression, the multiscreen panoramic cinema was again “invented” by Fred Waller for the 1939 World’s Fair. His Vitarama used eleven linked cameras and projectors to display a greatly enlarged image inside a hemispheric screen, while his enormous domed “movie-mural” within the fair’s Perisphere was even larger.7 While generating considerable excitement at the time, his work was also quickly forgotten. In the 1950s, multiple projection would once again be rediscovered by Hollywood as it desperately sought ways of contesting the falling box office receipts that attended the rising popularity of television. Cinerama, like its distant namesake, used linked cameras and projectors to create a single panoramic image, while Todd-AO, VistaVision, Cinema-Scope, and Ultra Panavision achieved a similar scale by means of larger film (Todd-AO), anamorphic compression (VistaVision, CinemaScope), or both (Ultra Panavision).

Contemporary advertisements for all three processes regularly invoked a similar rhetoric of immersion: the viewer did not watch at a distance, but was brought “inside” the spectacle. Often coupled with this immersivity was the promise of a new kind of “active” cinematic subject: a Todd-AO advertisement from the 1950s describes “a quality so perfect that the audience become part of the action, not just passive spectators.” This parody of the Brechtian imperative reveals the nature of this early industrial “expanded cinema.” Beyond the minutiae of diverse technological inventions, beyond the breathless publicity campaigns proclaiming the utter novelty of each newly minted procedure, we can locate a single, almost unwavering aim from the multiscreen Cinéorama of 1900 to the multiscreen Cinerama of the 1950s: the enfolding of the spectator in an immersive, diegetic world through the overwhelming sensory conditions of display. These supposedly radical innovations in multiscreen projection were, on a fundamental level, structured by a surprisingly fixed understanding of the spectator-screen relationship. By immersing the subject within an overwhelming accumulation of visual data, they sought to produce a heightened experience of reality without too great a concern for realism. Within industrial practice, the history of multiscreen technology might reasonably be considered little more than a footnote in the history of widescreen technology.8

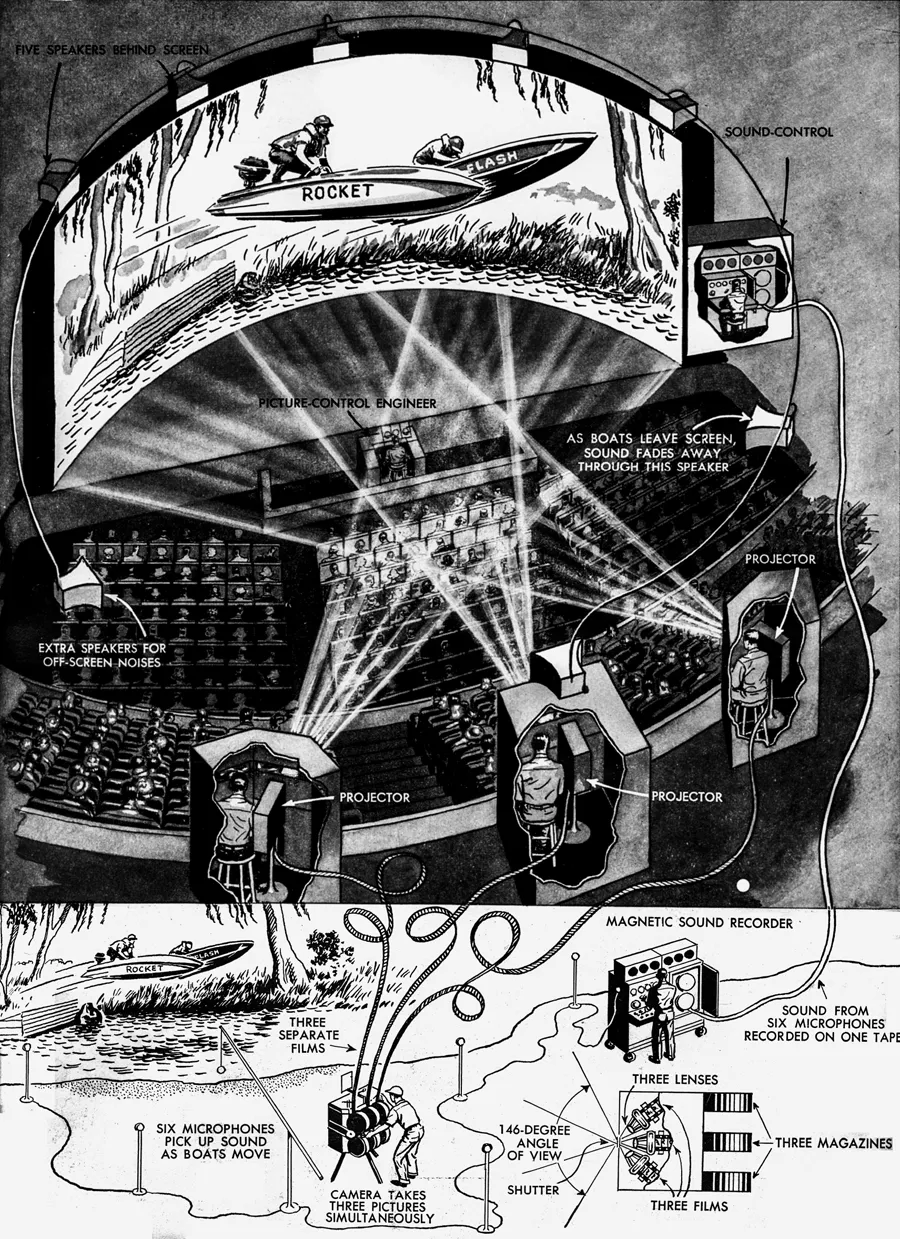

Figure 1.4. Schematic from This Is Cinerama souvenir book, 1951.

Figure 1.5. Comparison of widescreen processes.

As such, it should come as no surprise that the industrial adoption of CinemaScope in the 1950s and early 1960s would signal the obsolescence of multiscreen experimentation within the industrial cinema. Of the various processes, CinemaScope was clearly the least impressive, containing only a fraction of the visual or auditory detail of the other alternatives. Nevertheless, because it required only minor modifications to existing processes of production and distribution, it was considered the only economically feasible option for mass distribution. Using only a single lens, CinemaScope adequately addressed the desire for a larger and more immersive spectacle without the complexity and risk that attended multiple projection formats like Cinerama.

Returning to the ’64 World’s Fair with this history in mind, it is difficult to understand what was so wildly innovative about Thompson and Hammid’s piece. In his interview for Film Culture, Thompson claimed that To Be Alive! had not intended to subsume the multiple screens into a single, oversized image, yet all the evidence points to the film having precisely this effect. Maxine Haleff describes the width of the three screens as “enveloping” the viewer and producing an effect of “heightened reality.”9 The fair’s guidebook was even more explicit, advertising “the Tri-Screen System that puts you in the picture.”10 Both mirrored the rhetorical tropes regularly employed to advertise Cinerama, Todd-AO, and CinemaScope throughout the previous decade. In fact, Hammid was quite forthright in his description of the triple camera setup he had designed for the film: “the purpose is to have the cameras aligned so that the images coincide precisely.”11 In discussing those few sequences making simultaneous use of different images, Thompson spoke not of montage or juxtaposition, but of narrative efficiency: “We love this method, because we can say a lot more using less viewing time . . . in the pottery sequence, we show the beginning, middle and end of one process all at once, and it’s done.” Multiple images here do not disrupt or even complicate the narrative, they merely accelerate it. Thus, despite their implicitly disjunctive potential, multiple screens were understood principally as a means for creating a singular panoramic, introducing audiences to the “novel” experience of multiscreen spectatorship while keeping the resulting experience firmly within the comfortable conventions of industrial practice.12

Jonas Mekas—filmmaker, critic, and champion of the underground film community—was one of the few to dissent from the prevailing excitement over these new multiscreen spectacles. As the World’s Fair was wrapping up in the summer of 1965, he wrote that the idea of “expansion” presented within these new multimedia shows was simply a quantitative rather than a qualitative change: “Expanded consciousness is being confused with the ability to see more color images, with the expanded eye, with the quickness of the eye.”13 Mekas’s lament signals a prescient concern that, while shifting the formal vocabulary of cinematic representation, these works merely reiterated the same exhausted model of immersive spectacle that had characterized their historical predecessors for over half a century. The kind of “active” spectatorship these works proposed was not unlike those advertisements for Todd-AO and C...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Copyright

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: From Medium to Site

- 1. Rhetorics of Expansion

- 2. Leaving the Movie Theater

- 3. Moving Images in the Gallery

- 4. Cinema on Stage

- 5. The Festival, The Factory, and Feedback

- Epilogue: The Homelessness of the Moving Image

- Notes

- Illustration Credits

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Between the Black Box and the White Cube by Andrew V. Uroskie in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Arte & Arte generale. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.