eBook - ePub

Changing Minds or Changing Channels?

Partisan News in an Age of Choice

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Changing Minds or Changing Channels?

Partisan News in an Age of Choice

About this book

We live in an age of media saturation, where with a few clicks of the remote—or mouse—we can tune in to programming where the facts fit our ideological predispositions. But what are the political consequences of this vast landscape of media choice? Partisan news has been roundly castigated for reinforcing prior beliefs and contributing to the highly polarized political environment we have today, but there is little evidence to support this claim, and much of what we know about the impact of news media come from studies that were conducted at a time when viewers chose from among six channels rather than scores.

Through a series of innovative experiments, Kevin Arceneaux and Martin Johnson show that such criticism is unfounded. Americans who watch cable news are already polarized, and their exposure to partisan programming of their choice has little influence on their political positions. In fact, the opposite is true: viewers become more polarized when forced to watch programming that opposes their beliefs. A much more troubling consequence of the ever-expanding media environment, the authors show, is that it has allowed people to tune out the news: the four top-rated partisan news programs draw a mere three percent of the total number of people watching television.

Overturning much of the conventional wisdom, Changing Minds or Changing Channels? demonstrate that the strong effects of media exposure found in past research are simply not applicable in today's more saturated media landscape.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Changing Minds or Changing Channels? by Kevin Arceneaux,Martin Johnson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Journalism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University of Chicago PressYear

2013Print ISBN

9780226047300, 9780226047270eBook ISBN

9780226047447CHAPTER ONE

The Expansion of Choice

Walk into the average American home, turn on the television, and enter a variegated world of news and entertainment. The old standbys of the broadcast networks are in the lineup, with serious news programs at the appointed hour and soap operas, game shows, sitcoms, and dramas the rest of the time. Venture into the channels available through most cable packages and find ever more, specialized viewing choices. A half dozen channels or more are devoted to the news twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week. The shows on these networks range from the sedate anchor-behind-a-desk format to lively opinionated talk shows on which the hosts and guests lob invective and unsubstantiated claims without compunction.

Keep flipping the channel, and happen on all sorts of diversions from the worries and cares of the day. On MTV, to take one example of many, cameras follow Jersey Shore star Mike “The Situation” Sorrentino to the gym, tanning salon, laundromat, nightclubs, and back home. Elsewhere on cable television, viewers can find endless depictions of more interesting things like people building unique motorcycles, decorating impossibly elaborate cakes, crafting beautiful tattoos, rescuing endangered animals, and catching catfish with their bare hands. Of course, there are also stations devoted to second-run movies and fresh scripted dramas like Mad Men on the AMC channel.

It is not an exaggeration to say that the emergence of cable television has been revolutionary. Devised as a technology for bringing television to areas where broadcast signals founder, cable television also expanded the number of channels available for programming. In the 1970s, the average household in America had six or so channels from which to choose. Many of these were of poor broadcast quality on the UHF spectrum. By the end of 2010, the majority of homes—over 90 percent—have access to either cable or satellite television, giving the average home in the United States access to more than 130 channels (Nielsen Co. 2008).1

More channels translate into more choices, and the expansion of choice afforded by cable television has not only changed the face of television news and entertainment but also had profound implications for the reach and effect of news media.2 Before the rise of cable television, viewers could watch news programming a few times a day at fixed intervals and had little in the way of televised entertainment options during those newscasts (Prior 2007). In contrast, today’s cable television provides something for almost everybody (Webster 2005). The array of choices is vast, and the content itself is more varied and increasingly specialized as television programmers seek audience niches (Mullen 2003).

Four decades ago, when cable television was a far less developed resource, the trustees of the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation commissioned respected political leaders and scholars to assess the cable television industry of the day and forecast its harms and benefits in the future.3 The report that emerged from the Sloan Commission saw much potential in the new medium and the potential viewing options that it might eventually offer (Parsons 2008; Mullen 2003). It viewed cable television as a boon to viewers, particularly the possibility that the expansion of programming it afforded would help edify the public:

[Cable television] cannot, of itself, create a politically aware citizenry, for no one can be forced to twist the dial to the channel carrying political information or political news. But cable television can serve, as perhaps no medium before it has been able, those who wish to be part of the political process, and skillfully used it might very well be able to augment their number. . . . Politics, whatever opprobrium may sometimes be attached to the word, is important. The cable can literally bring that fact home, and in doing so help the entire political process function efficiently and effectively in the public interest. (Sloan Commission 1971, 122)

As with many other innovations, however, cable television has seen its promise give way to disappointment. Instead of supplying the public with the informative and edifying content envisioned by the Sloan Commission, cable news outlets have become purveyors of pitched, partisan discourse. Many see the news channels that have emerged on cable television as a nuisance at best and more likely a destructive force in the American polity.

In particular, the emergence of partisan news options on cable television has led many observers to fret that the expansion of choice has enabled people to live in a world where facts neatly fit their ideological preconceptions, enabling them to wall themselves off from reality (Manjoo 2008; Sunstein 2007). We agree that the partisan news offered by cable television makes this possible, but it is only one aspect of the new media environment. The choices available to viewers today go well beyond public affairs programming. There is a world of far less meaningful programming being issued on entertainment channels. Although it receives less attention from scholars who study news media, the expansion of entertainment choices is just as important a phenomenon as the rise of partisan news shows because it alters the reach and influence of news media. If we wish to understand how partisan news media shape people’s political views and behavior, we cannot study them in a vacuum. At the same time, Rachel Maddow (MSNBC) and Sean Hannity (Fox News) have become household names in certain, distinct households; so have people like “The Situation” (MTV), Kim Kardashian (E! Entertainment Television), and Cesar Milan, the Dog Whisperer (National Geographic Channel).

In this book, we investigate media effects in the context of choice. The television landscape has changed dramatically in the types of programs it offers viewers and the sheer number of them. We are most interested in the political implications of this expansion of viewing options—in particular, the claims that the new cable news, featuring the expression of politically ideological reporting, polarizes the public, affects distinct partisan issue agendas, and diminishes confidence in political and social institutions. We argue that television viewers are active participants in the media they consume. They are not, as many scholars and media observers implicitly assume, an inert mass, passively and unquestioningly soaking in the content to which they are exposed. They make choices about what to watch on television—be it partisan news or something else—and those choices shape how they react to the content they view.

Placing Partisan News Media in the Context of Choice

Ideologically slanted news is certainly available today, primarily on Fox News and MSNBC. If the presence of these partisan news shows is not bad enough, many scholars and public intellectuals worry that “the inclination to seek out or selectively expose oneself to one-sided information” creates a public that is increasingly encouraged to view the world from only one’s own point of view and that, as a result, adopts more extreme and polarized political attitudes (Jamieson and Cappella 2008, 214; see also Stroud 2008, 2010). As people are “exposed largely to louder echoes of their own voices,” the result is likely to be “misunderstandings and enmity” (Sunstein 2007, 73) as well as the creation of “parallel realities” in which liberals and conservatives no longer share even the same facts (Manjoo 2008, 25). These worries coalesce into the broader concern that the rise of partisan news on cable television threatens the functioning of American democracy as politics increasingly becomes two strongly opposed ideological camps talking past each other rather than deliberating toward sound public policies on matters of collective, and not particular, concerns.

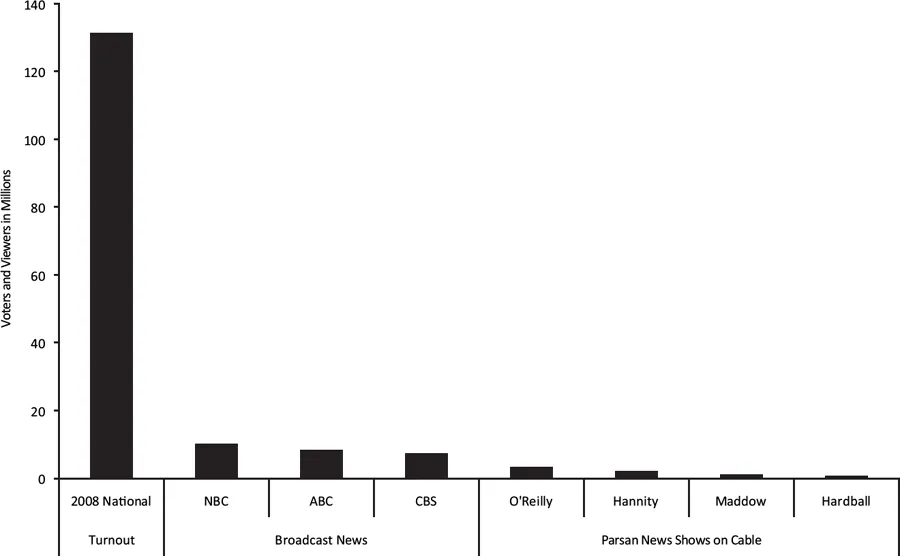

The partisan news media may indeed have a deleterious effect on democracy, but we doubt that partisan news shows are directly responsible for polarizing the mass public. For one, partisan news shows attract small audiences. The week of January 16–20, 2012, offers a more or less representative snapshot of broadcast and cable news audiences. According to the Nielsen Media Research Group, which rates television programs, the top-rated prime-time partisan news programs drew in anywhere from 0.8 million (Hardball with Chris Matthews) to 3.4 million (The O’Reilly Factor) viewers, on average. In contrast, the broadcast evening news programs drew 7.4 million (NBC) to 10.2 million (CBS) viewers, on average. This broadcast news audience is smaller than it was in the past (Webster 2005), but it is more than three times the size of the partisan news audience. Even if we assume that there is no overlap in partisan news audiences, the four top-rated shows draw roughly 7.5 million viewers on any given day. This is a large number of people to be sure, but, as figure 1.1 shows, it pales in comparison to the 130 million individuals who vote in national elections.

FIGURE 1.1. News audiences and the national electorate.

Source: Nielsen Media Research Group as reported by TV by the Numbers (2012a, 2012b).

Note: Bars represent average viewers per day (in millions) during the week January 16–20, 2012.

Not too long ago, things were different. In the 1970s, most people got their news from one of the three major broadcast networks (ABC, CBS, or NBC). The news shows on these networks were nearly identical: an anchor sitting behind a desk reading the news and showing video footage of events. Reporting followed shared standards of objective journalism. Remove, balance, fairness to all sides, and impartiality were the goal in network reportage. The reporter and the news anchor were cast in the role of Joe Friday, the fictional police detective on the hit 1950s television show Dragnet: “All we know are the facts, ma’am.” What is more, many Americans watched the news simply because there was little else to watch (Prior 2007).

Today, television programming is so diverse that it can precisely map to the interests of its viewers. The vast array of choices viewers have at their disposal allow Americans to watch only news by tuning in to twenty-four-hour cable news channels or to avoid watching any news at all (Bennett and Iyengar 2008; Prior 2007). Analyses that draw a straight line from the content of partisan news shows to normatively undesirable political outcomes, such as polarization or declining trust, often fail to appreciate that the availability of so many viewing options gives people unprecedented control over the content they consume on television. People do not have to watch the news because they lack other alternatives. There is a plethora of entertainment options, which should limit the reach of partisan news and substantially blunt its direct effects on American society.

Some may consider the limited reach of partisan news a good thing, and others may consider it too good to be true. However, the downside we suggest is that this abundant choice also means that the capacity of television to educate its viewers and to engage them in public life is also limited. Television informs the informed who want to learn more. It provides specialized knowledge to particular people—information about partisan politics to partisans, home-improvement training to people who like that sort of thing, and so on. The partisan media must be placed in this context of expanded choice if we are to understand their effects.

Partisan News Media Require a New Kind of Media Effects Research

In the early years of the twentieth century, the seemingly successful use of mass communication to rally the country behind World War I led many scholars to worry that their expansive reach would give media unparalleled power to shape and mold mass attitudes (Lasswell 1938/1972; Lippmann 1922/1965). The rise of the Nazi Party in Germany and its masterful use of propaganda to maintain power and motivate unspeakable acts of violence and genocide only fueled such concerns. In these early models of media effects, consumers of mass media were characterized as easily manipulated victims. Subsequent scholars derisively described these models as treating the mass media like a “hypodermic needle” that injected propaganda into the veins of consumers who could not resist its effects (Berelson, Lazarsfeld, and McPhee 1954). By midcentury, the pendulum had swung in the opposite direction. Failure to find consistent and lasting media effects through quantitative empirical research (e.g., Hovland 1954; Lazarsfeld, Berelson, and Gaudet 1948) led Joseph Klapper (1960) to declare in The Effects of Mass Communication, his influential meta-analysis: “Mass communication ordinarily does not serve as necessary and sufficient cause of audience effects, but rather functions among and through a nexus of mediating factors and influences” (8). Communication designed to persuade, in particular, “functions more frequently as an agent of reinforcement than as an agent of change” (15).

Soon after the “minimal effects paradigm” became the dominant framework, scholars began to consider the more subtle and nuanced ways in which the media could influence mass attitudes. They eschewed the early fascination with persuasion, focusing instead on the ways in which news media can set the agenda by reporting on some issues at the expense of others (Cohen 1963; McCombs and Shaw 1972). By setting the agenda, news media are capable of influencing the criteria by which citizens evaluate public officials (Iyengar and Kinder 1987). Moreover, in the process of creating a narrative, even news stories that attempt to be balanced end up defining issues in particular ways. The “frame” of a news story has the ability to shape how people think about an issue and, in turn, conceptualize the solution (Iyengar 1991).

Research on the effects of partisan media brings the study of persuasion effects back into focus. Unlike mainstream media news, the ostensible goal of partisan news is to persuade. Recently, scholars offer evidence that exposure to partisan media does persuade (Feldman 2011), polarize attitudes (Jamieson and Cappella 2008; Stroud 2011), and misinform (Fairleigh Dickinson University 2011; Ramsay, Kull, Lewis, and Subias 2010). Besides being designed to persuade, partisan media are also designed to bolster and reinforce the preexisting attitudes of like-minded viewers, suggesting that attitude reinforcement, which was seen by Klapper as evidence of the media’s minimal effects, should be reconceptualized as a media effect (Holbert, Garrett, and Gleason 2010; Levendusky 2012). Evaluating the potential for the partisan media to create insular worlds in which Manjoo’s “parallel realities” exist requires that we reconsider the nature of agenda-setting effects in a media environment that features multiple conversations rather than a common one (Mutz and Martin 2001). The content of partisan media is also in direct contrast to the genteel world of mainstream news. Hosts yell at guests, their absent opponents, and the audience. Pundits make dramatic and histrionic claims. Heated arguments are frequent. These displays of hostility and aggression may serve only to damage viewers’ trust in news media (Coe et al. 2008; Ladd 2010) and the political system (Mutz and Reeves 2005).

Competing Models of Viewing Behavior and Reception

In much the same way as scholars in the mid-twentieth century found, how we conceptualize viewers shapes how we think about and, ultimately, investigate partisan media effects. In this section, we contrast the model implicit in many current accounts of partisan media effects with the theoretical model we offer in this book.

Passive Reception

In the pursuit of cataloging the effects of partisan media, previous scholarship has implicitly adopted a hypodermic needle model of reception in three important respects. First, these researchers ignore political avoidance and proceed as if exposure to partisan news is ubiquitous. Second, they implicitly assume that exposure to news has strong direct effects on political attitudes. Third, they treat viewers as passive recipients of partisan news media. Take Jamieson and Cappella’s (2008, 216) argument as a representative example: “In circumstances in which an audience is exposed regularly to a single, coherent, and consistent point of view and the voices championing that in-group view identify alternative points of view as suspect, the audience’s dispositions would be expected to be reinforced or made more extreme.” Partisan news is like a powerful, addictive drug that people are powerless to resist once exposed to it.

Interestingly, while research in this vein implicitly characterizes reception as passive, many scholars view the decision to seek out attitudeconsistent information as a facilitator of media effects rather than a foil, as those in the minimal effects tradition saw it. Part of the difference in interpretation lies in the fact that the partisan media wish to reinforce preexisting attitudes through selective exposure, whereas the persuasive communication that Klapper considered was designed to convert mass audiences (e.g., campaign propaganda). Consequently, scholars today are more likely to view selective exposure as a key mechanism through which partisan media are able to bolster and polarize the attitudes of their audience members. Selective exposure to like-minded news creates a “reinforcing spiral” wherein the viewer’s attitudes become more extreme, which in turn feeds their desire to consume more like-minded media (Slater 2007).

Nonetheless, many models of partisan media effects do not characterize audiences as active beyond their decision to consume partisan news, and even here an individual’s decision to watch partisan media, like-minded sources in particular, is treated almost like a moth’s attraction to the flame. The passive audience assumption is all the more obvious when we consider that the antidote to the reinforcing spiral is exposure to alternative viewpoints (e.g., Jamieson and Cappella 2008, 83–84; Sunstein 2007, 158). If only people exposed themselves to news media that present ideas contrary to their predispositions, the argument goes, the effects would go in the opposite direction and mode...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Copyright

- Title Page

- Series Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- 1. The Expansion of Choice

- 2. Changes in Media Technology and Content

- 3. Selective Exposure and Media Effects

- 4. Partisan News and Mass Polarization

- 5. Hearing the Other Side and Standing Firm

- 6. The Salience and Framing of Issues

- 7. Bias and incivility in Partisan Media

- 8. Media Effects in the Age of Choice

- Appendices

- Notes

- References

- Index

- Series List