eBook - ePub

Serious Whitefella Stuff

When solutions became the problem in Indigenous affairs

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

How does Indigenous policy signed off in Canberra work-or not-when implemented in remote Aboriginal communities? Mark Moran, Alyson Wright and Paul Memmott have extensive on-the-ground experience in this area of ongoing challenge. What, they ask, is the right balance between respecting local traditions and making significant improvement in the areas of alcohol consumption, home ownership and revitalising cultural practices?Moran, Wright and Memmott have spent years dealing with these pressing issues. Serious Whitefella Stuff tells their side of this complex Australian story.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Serious Whitefella Stuff by Mark Moran in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Histoire & Histoire sociale. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The More Things Change

Mark Moran

THE INTRACTABILITY OF INDIGENOUS disadvantage in Australia is undeniable. According to the United Nations, Australia is one of the richest countries in the world, second only to Norway.1 Universal welfare entitlements ensure a comparative lack of poverty, by international standards, but pervasive inequalities persist, most notably among Indigenous Australians.2 In 2012, household income for Indigenous people was a little over half that of non-Indigenous people. The unemployment rate was five times higher. Two-thirds of Indigenous students completed Year 12 compared to their non-Indigenous counterparts.3 Indigenous men and women experienced double the rate of physical violence during their lifetime.4 Indigenous youth were twenty-four times more likely to be locked up in detention centres.5 The life expectancy for Indigenous Australians was sixty-nine years for males and seventy-four years for females, a difference of around ten years in comparison to the non-Indigenous population.6 While there has been progress in life expectancy and secondary education since 2008, literacy and numeracy have remained resistant to improvement and employment levels have actually declined.7 Indigenous disadvantage in Australia has also proven to be higher and more intractable than that experienced by their Indigenous counterparts in Canada, New Zealand and the United States.8

Intense public debate has ensued about the underlying causes and possible solutions. With its full might as a developed nation, Australia has thrown its considerable administrative machinery and public finances at the problem, leading to a proliferation of program and service providers. The services, collectively provided, cover most aspects of life, including housing, early childhood, aged care, sports, community justice, child protection and household financial management. The three levels of government—Commonwealth, state/territory and local—each has separate administrative arrangements. Indigenous organisations play a major role, generally operating under service delivery contracts to government. Reforms during the 2000s introduced a range of new operators.9 Multiple service providers, including government agencies, Indigenous organisations, not-for-profit non-government organisations (NGOs) and for-profit contractors, now compete in the same small locales. The institutional landscape of Indigenous affairs has become highly crowded, complex and fragmented.

Policies and programs are forever undergoing reform. New conceptualisations of the ‘problem’ result in new policies and programs, each being laid over the partially implemented ‘failures’ of the past. The rate of launching new programs exceeds their closure, resulting in an annual increase in the quantity of programs. At the conclusion of a Council of Australian Governments (COAG) trial at Wadeye in the Northern Territory—a reform specifically targeting improved coordination—the number of funding agreements increased by 50 per cent, from sixty to more than ninety.10 Julalikari Council Aboriginal Corporation, which manages programs for Tennant Creek and surrounding communities in the Northern Territory, acquitted eighty-one separate government grants in the 2011–12 financial year.11

A 2012 audit by the Australian National Audit Office revealed the sheer number of small, short-term grants awarded to Indigenous organisations.12 The Indigenous organisations funded under one grant system were required to submit on average twenty-five different financial and acquittal reports. The average duration of these grants was fifteen months. The Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs funded the largest number of organisations, and more than half of these were less than $55 000 in value, and a not insubstantial proportion were for less than $1000. The audit was unequivocal: the administrative burden imposed by such a high number of short-term and small-value grants, undermined the capability of Indigenous organisations that they were intended to assist.

Australia spends more than double the amount per capita on programs and services for Indigenous people than for the rest of the population.13 Nationally, an estimated $5.6 billion in government funding is allocated to Indigenous-specific programs. If the total level of servicing is included, by adding mainstream services like health, education and policing, the total figure is just over $30 billion.14 So what has been the result? The Department of Finance and Deregulation’s ‘Strategic Review of Indigenous Expenditure’ answered ‘this major investment, maintained over many years, has yielded dismally poor returns to date’.15 It blamed the familiar litany of under-performing programs, poor coordination across governments, and the lack of engagement with Indigenous peoples in design and delivery.

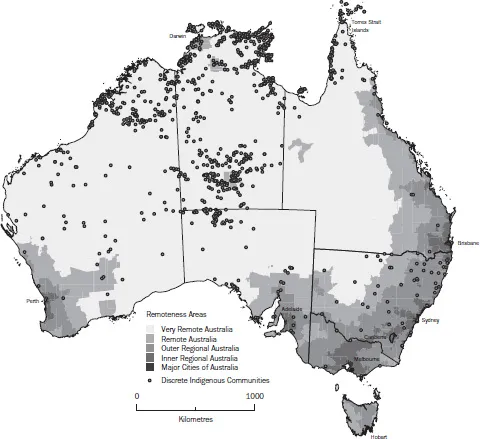

The problem is most acute for the 21 per cent of Australia’s Indigenous population who live in remote areas, who are Australia’s most disadvantaged communities.16 Remote Indigenous communities are marginalised socially and geographically, and governments face many cultural and logistical challenges in delivering services to them.17 These settlements operate in an extreme economic context, arising from limited economic opportunities, a lack of local capability, their small size and isolation, and the mobility of people between them. Aboriginal people in these remote settlements follow their social and cultural traditions more strongly than in regional and urban areas. The scale of public resources directed to alleviate their disadvantage has led to intense public debate about their ‘fiscal sustainability’. In late 2014, following a withdrawal in municipal funds by the Commonwealth, the Premier of Western Australia Colin Barnett announced the closure of between 100 and 150 remote outstations and communities. Then prime minister Tony Abbott weighed in saying: ‘What we can’t do is endlessly subsidise lifestyle choices if those lifestyle choices are not conducive to the kind of full participation in Australian society that everyone should have’.18 Following a national outcry including a number of public demonstrations, Barnett backed down, laying out a more reasoned policy.20

Discrete Remote Indigenous communities. Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics.19

In threatening to close remote communities, government is not exercising powers through land title or resettlement legislation. Rather, it is exercising its power to withdraw funding and services and so rendering the settlements unviable. Public funding dominates the economies of remote Indigenous settlements, through government expenditure in the form of grants and welfare payments. These return a limited local circulation, mostly through the community store, although these too are generally externally managed and operated by a government agency, regional Indigenous organisation or NGO.21 There is typically very little local private economic activity, by way of retail stores, cottage industry or markets, other than Indigenous art sales, ecotourism and occasionally ecosystem services such as carbon farming. Local employment is otherwise limited to community administration and service delivery positions, with management and professional positions often filled by outsiders. Private sector employment and small enterprise are largely confined to the few settlements located near enclaves of global mining investment. Other economic benefits from mining are still to a large degree shaped by the political bargaining through which mining royalties are publicly distributed.22 There is very little internal capital, remittances, personal savings or disposable income against which to leverage socioeconomic development.23 For all the frustrations and opportunities they bring, government policies and expenditure largely define what the outside world and economy are to remote communities. In this context, policies, services and payments assume a disproportionate importance beyond that experienced by other Australians, and in many ways define the potential for socioeconomic development. For this reason alone, it’s important to understand what is actually happening with policy and how it actually unfolds in practice on the ground.

PUBLIC OPINION and media are potent drivers of Indigenous affairs policy. There was a string of shocking media reports of child neglect and abuse in remote Indigenous communities through 2006 and 2007. The Howard Government’s response was to launch the Northern Territory Emergency Response (the Intervention) in the lead-up to the 2007 federal election. At a time when his government was trailing in the polls, was a legitimate concern for citizen welfare weighed against the political gains of ‘sending in the troops’? Academic economist Boyd Hunter questioned the timing—as the reports of child abuse had long been known—and the military framing of the response.24 He also questioned why the Intervention was limited to the Northern Territory, as the then known cases of child abuse and neglect among Indigenous children was lower compared to other jurisdictions.25

Australian Research Council research through the University of Canberra explored the extent that politicians and policymakers respond to media. They found ‘that once an issue became the subject of sharp media focus in times of intense political contest, political leaders would shift policy’. Policymakers were found to closely monitor media outlets, anticipating media coverage on their policy areas, practising media messaging, and adapting policy decisions to account for the positive or negative news stories to come.26 The research revealed a bureaucracy that was strongly reactive to the daily media cycle, ‘capable of responding with alarming speed to new media imperatives’. Few journalists were interested in the intricacies and complexities of policy responses and their implementation in practice; the ‘story’ is usually in the human crisis and government failure.27

With the exception of some parts of the Northern Territory, Indigenous people are not in sufficient number or political alignment to constitute a significant political force at the federal or state ballot boxes. It is surprising then how much influence these few voters hold over public sentiment. A political reality of Indigenous affairs is that public opinion in coastal and regional Australia is as important in policy formation as the voice of remote Indigenous citizens. The clients of Indigenous affairs policy thus strongly include non-Indigenous Australians.28

The counterpoint to this is that a crucial role of Indigenous leaders and organisations becomes one of political advocacy—often escalating the human crisis and government failure—to garner the attention of the public and politicians. National Indigenous leaders pragmatically accept that if they are to be effective change agents, they must have a public profile and be effective in media management. Faced with the threat of damning media coverage, the bureaucracy in turn becomes risk averse, producing ‘bureaucratic involution in which inner-directed activities such as planning and reporting take precedence over outer-directed program delivery’.29

Given this high profile in public attention, is it a coincidence then that certain welfare reforms first appear in Indigenous communities, before they are mainstreamed? Income management is a policy where a portion of welfare payment is managed so as to restrict the ways that it can be spent, rather than being paid directly in cash. The Commonwealth Government first introduced income management to seventy-three remote Indigenous communities as part of the Northern Territory Intervention in 2007. In 2010, they extended it to non-Indigenous welfare recipients in the Northern Territory. In 2012, they began rolling out trials in a number of depressed regional centres across Australia, including major urban centres.30 In Bankstown, Shepparton, Logan, Playford and Rockhampton, more than 80 per cent of participants were non-Indigenous.31

If the recommendations of the Abbott/Turnbull Government’s Forrest Review into Indigenous Disadvantage are impl...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the Authors

- Foreword by Noel Pearson

- 1 The More Things Change

- 2 Prohibiting Alcohol in Kowanyama

- 3 Moving to Outstations at Doomadgee

- 4 Reviving Culture on Mornington Island

- 5 Sharing Responsibility at Ali Curung

- 6 Planning the Return to Mapoon

- 7 Owning a Home in Mapoon

- 8 Why Practice Triumphs over Policy in Indigenous Affairs

- Notes

- Acknowledgements