- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Since the time of Aristotle, the making of knowledge and the making of objects have generally been considered separate enterprises. Yet during the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, the two became linked through a "new" philosophy known as science. In The Body of the Artisan, Pamela H. Smith demonstrates how much early modern science owed to an unlikely source-artists and artisans.

From goldsmiths to locksmiths and from carpenters to painters, artists and artisans were much sought after by the new scientists for their intimate, hands-on knowledge of natural materials and the ability to manipulate them. Drawing on a fascinating array of new evidence from northern Europe including artisans' objects and their writings, Smith shows how artisans saw all knowledge as rooted in matter and nature. With nearly two hundred images, The Body of the Artisan provides astonishingly vivid examples of this Renaissance synergy among art, craft, and science, and recovers a forgotten episode of the Scientific Revolution-an episode that forever altered the way we see the natural world.

From goldsmiths to locksmiths and from carpenters to painters, artists and artisans were much sought after by the new scientists for their intimate, hands-on knowledge of natural materials and the ability to manipulate them. Drawing on a fascinating array of new evidence from northern Europe including artisans' objects and their writings, Smith shows how artisans saw all knowledge as rooted in matter and nature. With nearly two hundred images, The Body of the Artisan provides astonishingly vivid examples of this Renaissance synergy among art, craft, and science, and recovers a forgotten episode of the Scientific Revolution-an episode that forever altered the way we see the natural world.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Body of the Artisan by Pamela H. Smith in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & History of Art. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University of Chicago PressYear

2018Print ISBN

9780226764238, 9780226763996eBook ISBN

9780226764269PART ONE

FLANDERS

1

The Artisanal World

Artisanal Self-Consciousness

In seeking out an artisanal worldview, we can look to the objects artisans fashioned, to the texts they wrote, and, as we saw in the case of Messerschmidt, to literate intermediaries who put their actions into a form both comprehensible and accessible to a wider audience. Before the beginning of the fifteenth century, we have very few texts written by artisans, but around 1400 artisans appear suddenly, in the words of one historian of technology, to “resort to pen and paper in a field where their fathers had been satisfied with memory and the spoken word.”1 The result was a veritable explosion of technical treatises between 1405 and 1420. The artisans of northern Italy and southern Germany seemed to have felt particularly compelled to write down their modes of working, especially those in architecture, fortification building, and gunnery.2 Historians have largely accounted for this sudden shift from oral transmission to the medium of written treatises by pointing to new methods of warfare and the greater fragmentation of Europe into competing noble territories. A new political culture emerged out of these changes that gave artisans and their handwork a newly perceived importance in society.3 Furthermore, these writing artisans stood at the intersection of courtly and commercial forces. Freed from (or never possessing) guild membership by the rise of the courts and the greater intensity of commerce, artisans were forced to become more self-conscious about their practices and to make explicit claims for their skill and power because they were competing for patronage, livelihood, and fama.

The number of practicing artisans who combined craft with authorship is striking in this period, even if we consider only a few of the best-known “high” artists of Italy: Lorenzo Ghiberti (ca. 1378–1455), who created the relief panels of the Florentine Baptistry doors, wrote a treatise on sculpture in 1447; Antonio Averlino (ca. 1400–ca. 1469), called Filarete, who was trained as a goldsmith, dedicated an architectural treatise to Francesco Sforza in the early 1460s; Piero della Francesca (ca. 1420–1492) wrote tracts on perspective and practical mathematics; and, finally, Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) wrote notes and treatises that were never published and, like many of the others, painfully taught himself Latin.4 These artisan-authors represent one stream of a confluence of humanist and artisanal interest (often in the service of the same noble courts) in architecture, fortification, mechanical problems, practice, praxis, and the common good. Scholars began expressing interest in the crafts for at least two reasons. First, because artisans had become economically and politically powerful and their products had come to be regarded as integral to the common good, and, second, because humanists saw the practical knowledge of artisans as a model of praxis that could be set against contemplation. The result of this confluence was a set of shared values: an emphasis on the union of practice and theory, and on the need to relate mathematics to practice and experience. As Pamela O. Long puts it, artisans’ books enabled the mechanical arts to become “central features of moral and political life, as they also began to take part in the construction of knowledge itself.”5 Long makes the argument that humanists and artisans shaped a set of values for the pursuit of knowledge6 and that the treatises and books of artisans contributed substantially both to the formation of these values and to the construction of new knowledge.

Self-Consciousness and Naturalism

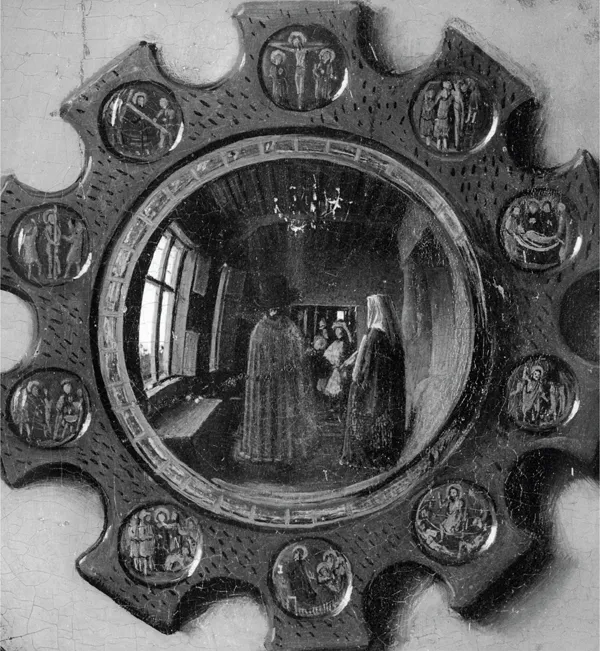

At about the same time, another type of artisan began to articulate his mode of working, not by writing, but by producing a new naturalistic representation of nature (plate 1, figs. 1.1, 1.2). Fourteenth-century Italian artists had “developed a wide variety of stratagems for the evoking of space and for the depiction of solid forms in a more or less convincing manner,”7 culminating in about 1340 in a rudimentary system of perspective construction. By 1400 Filippo Brunelleschi (1377–1446) was beginning his experiments with perspectiva to represent the buildings of Florence on small panels using painters’ perspective. The aim of art was shifting from evoking an image of the form of the thing depicted to, as Leon Battista Alberti (1404–1472) put it in about 1435, making a picture that was an “open window” through which the world was seen.8 The development of perspective in the Italian Renaissance has been extensively studied, but the almost contemporaneous development of naturalistic depictions of nature has not inspired nearly the same interest. This naturalistic art—beginning in northern Italy and spreading to Flanders, aided by close commercial ties—does not show the use of mathematical perspective construction (although the use of the vanishing point appeared in the north in about 1370), but instead employed a particularizing light and multiple points of observation, and, especially in the portraits, exhibited an interest in individual detail unmatched in Italy at this time.

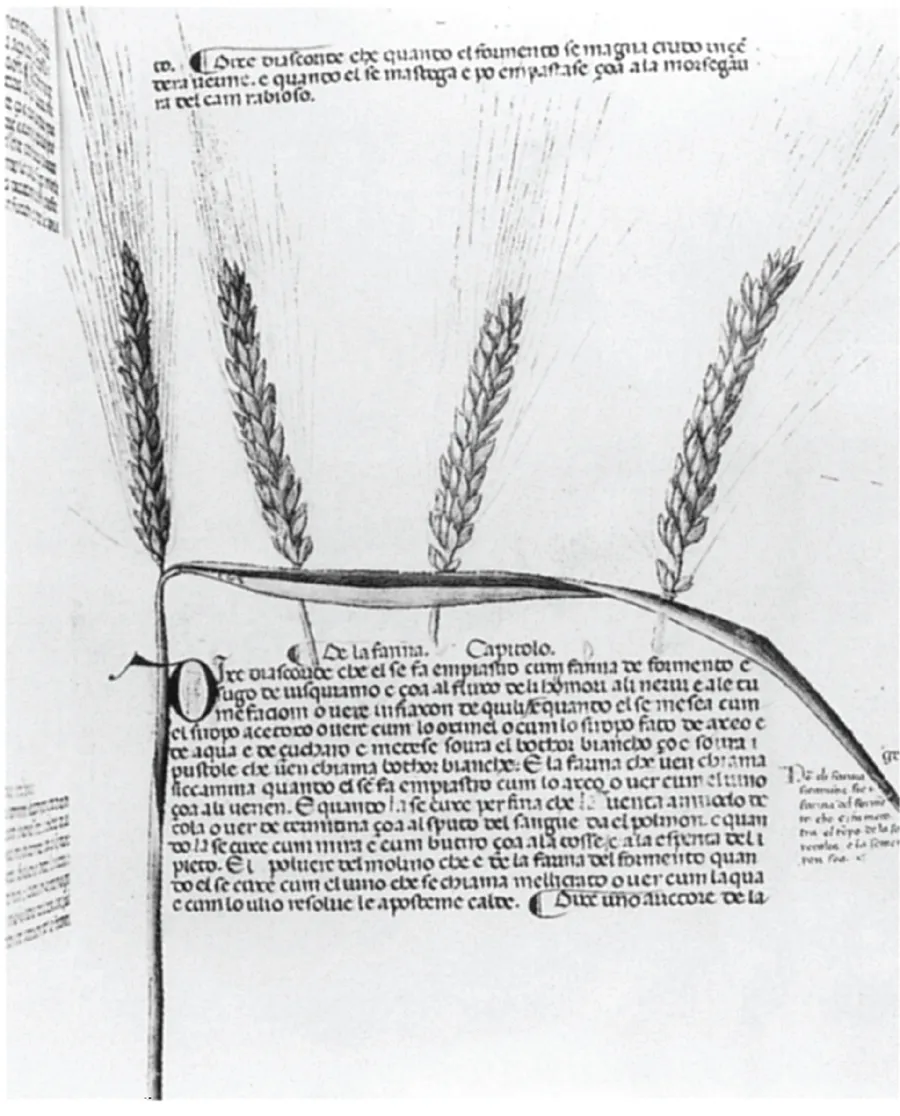

FIGURE 1.1.

“Ear of Grain,” from the Carrara herbal, 1375–1400, Egerton 2020, f. 21r, by permission of the British Library. Here the anonymous artisan depicts the progression of ripening wheat, starting on the left with delicate green, tightly nestled kernels and ending on the far right, where the open, mature kernels are on the verge of drying (indicated by yellow and white highlights) and some grains have already fallen from the stem.

“Ear of Grain,” from the Carrara herbal, 1375–1400, Egerton 2020, f. 21r, by permission of the British Library. Here the anonymous artisan depicts the progression of ripening wheat, starting on the left with delicate green, tightly nestled kernels and ending on the far right, where the open, mature kernels are on the verge of drying (indicated by yellow and white highlights) and some grains have already fallen from the stem.

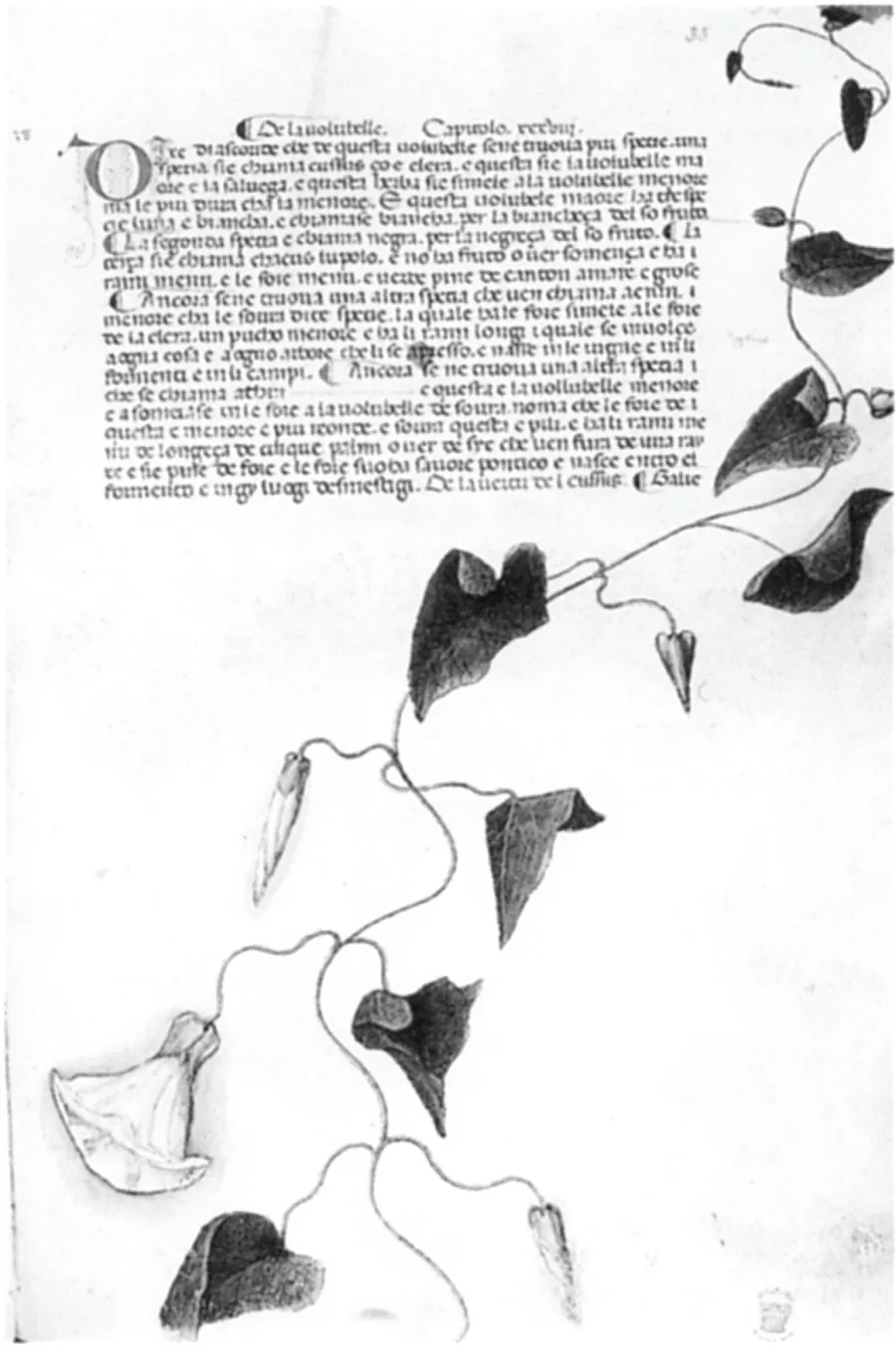

FIGURE 1.2.

“Convolvulus,” from the Carrara herbal, 1375–1400, Egerton 2020, f. 33r, by permission of the British Library. Like the ears of wheat, the depiction of the convolvulus, or morning glory, is concerned with the plant’s progression from bud to flower. The artist’s focus seems to be more on painterly illusion than on the full botanical information that would have been provided had the artist represented the full plant including the roots.

“Convolvulus,” from the Carrara herbal, 1375–1400, Egerton 2020, f. 33r, by permission of the British Library. Like the ears of wheat, the depiction of the convolvulus, or morning glory, is concerned with the plant’s progression from bud to flower. The artist’s focus seems to be more on painterly illusion than on the full botanical information that would have been provided had the artist represented the full plant including the roots.

Otto Pächt has traced the new depictions of nature back to a tradition of botanical illustration, the ultimate source for which was an eleventh- and twelfth-century revival of medicine under the influence of Arabic medical and scientific activity in Salerno. An herbal produced in Padua around 1400, called the Carrara herbal, emerged out of this tradition, but the naturalism of its illustrations (plate 1, figs. 1.1, 1.2) was without precedent in earlier herbals.9 It is a vernacular Italian translation made in the closing years of the fourteenth century of the Liber Serapionis aggregatus in medicinis simplicibus by the ninth-century Arab author Serapion the Younger (Ibn Sarabi) on medicinal plant simples. The illustrations in this codex all include close observation and some are drawn from pressed specimens (plate 1), practices probably partly associated with the medical faculty at the university in Padua. Yet these illustrations are not strictly descriptive, that is, they do not always adhere to the function of an illustration in a medicinal herbal, as they do not represent complete botanical specimens, often lacking root, stalk, leaf, flower, or fruit.10 As Pächt notes, this is significant because it indicates the dawning of a painterly aesthetic, in that it both begins “to see in plant portrayal an aesthetic problem” and deliberately confuses painted and real space (thus is illusionistic). It is also significant as an expression of empiricism; as Pächt puts it: the illustrator “is an illusionist who prefers the empirical truth of the one-sided view to the lifeless completeness of an abstract image.”11 Pächt goes on to speak of this illustrator’s “courage to turn his back on all patternbooks and to look nature straight in the face.”12 I would argue that this empiricism comes not so much out of the heroic mix of science and art posited by Pächt, but, rather, out of a new self-consciousness on the part of the artisan. Caught between patronage and market forces similar to those that operated on fortification builders and gunners,13 this artisan articulated his methods not in treatises, but in paint.

The Carrara family, rulers of Padua from 1318 to 1405, commissioned what came to be known as the Carrara herbal, and their interests contributed to the self-consciousness of the artist and the new attitude toward nature evident in it. Besides employing the artist who illustrated the Carrara herbal, they commissioned remarkably naturalistic portraits, and their funerary monuments show evidence of the sculptors having worked from death casts of their faces and hands. Their palace was painted with lifelike animals. Under their patronage, the painter Cennino d’Andrea Cennini penned Il libro dell’arte, a manual for painters, in which he states that painting is the imitator of nature and describes the technique for exact replication by casting from life for the first time since antiquity.14 Much more will be said about Cennini and casting from life in the following chapters, but it is important to note here that Cennini’s treatise signals both a self-aware artisan concerned with justifying the mechanical arts and a potent interest in nature at the Carrara court. The interest in nature on the part of the Carrara family was undoubtedly related to their own precarious and “unnatural” hold on power. The family had risen through the communal government of the city, from which they had subsequently seized power, with the result that they possessed political legitimacy neither from pope nor emperor. Instead they based their authority on the language of the jurists at the university in Padua who claimed that government must imitate nature; the same kind of language the commune had employed when it originally separated itself from the local seigneury. Claiming the natural reasonableness of their rule, the Carrara family thus walked an uneasy course between the claims of the commune that they were unnatural tyrants and the assertions of the pope that they stood outside any divinely ordered hierarchy.15 They appear to have employed nature (and artisans) to construct a theater of state that would make authoritative their claims to legitimate rule, or, at the very least, they used nature as a way to display their mastery. The naturalism of the Carrara herbal was an artisan’s response to this discourse about nature and also a statement of the importance of his own part in the construction of this theater of state. In this respect, the herbal’s illustrations are analogous to Cennino Cennini’s written treatise on painting. Both come out of the elevation of the artisan and of nature in the theater of state that constituted a central mode of governing at the Carrara court.

As Pächt notes, the fruits of this attention to the details of nature were not reaped in Italy, where only Pisanello made ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Copyright

- Title Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part One: Flanders

- Part Two: South German Cities

- Part Three: The Dutch Republic

- Conclusion: Toward a History of Vernacular Science

- Notes

- Bibliography

- List of Illustrations

- Index