![]()

Chapter 1 Introduction

Angela R. Glatston

Rotterdam Zoo, Rotterdam, The Netherlands

When the name “panda” is mentioned, the image that comes to most people’s mind is that of a clumsy-looking, black and white, bear-like animal; that is the well-known and much-loved symbol of the Worldwide Fund for Nature (WWF), the giant panda. However, this creature is not the only, nor even the first, species to bear the charismatic name “panda”. For nearly half a century a small, chestnut-coloured, cat-like animal was the only panda we knew which is why this book refers to the red panda as “the first panda”. It was not until 1869 that Père Armand David eventually encountered the species that we know today as the giant panda, a creature that owes its very name to its perceived similarity to the original panda. The discovery of this giant panda meant that the real panda’s name had to be changed to distinguish the two species. This is why the “first panda” is now better known as the red or lesser panda. Nevertheless, this panda remains unique in its own right. It is classified as a carnivore but it feeds almost entirely on bamboo, indeed, for a long time nobody was quite certain exactly to which family of mammals it belonged. It is a panda, which is not piebald but rather is flamboyantly clad in chestnut, chocolate and cream and is surely, as Frederic Cuvier is quoted as saying, “quite the most handsome mammal in existence” [1] (Figure 1.1; the original illustration of the red panda can be found elsewhere in this volume, see Figure 7.11).

It is not just the pandas themselves that are remarkable, their very name, “panda”, is of itself interesting, as its origin is uncertain. There are a number of theories about how it was derived, however, the most likely theory is that it comes from one of the local names for the red pandas, nigalya ponya; nigalya is thought to come from nigalo meaning cane or bamboo. The source of ponya is less certain, although it may come from ponja meaning the ball of the foot or the claws, if this is correct then nigalya ponya may mean bamboo footed, an appropriate name for either panda [2].

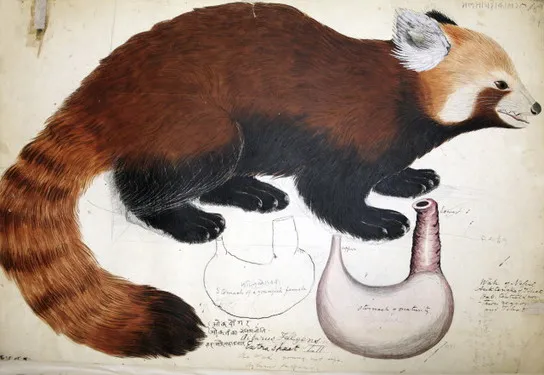

It is abundantly apparent that the red panda is an extremely attractive species and charismatic in its own right. Cuvier, who published the first description of the red panda, was only one among many to have remarked on its beauty and its charm [3,4] (Figure 1.2). Nor is it without friends in high places; Jawaharlal Nehru, the former prime minister of India, kept red pandas in his home where they were childhood pets of his daughter, another Indian prime minister, Mrs Indira Ghandi [5]. Yet, despite its beauty and connections, the red panda has remained relatively unknown to both scientist and layman alike. On the other hand, it would be untrue to say that nothing is known about the species; there have been a number of publications dealing with the red panda and its biology which have appeared in various journals and books, over the last hundred or more years. However, most of this information seems to have faded from our collective radar. This book aims to redress this situation and to focus attention on this rare and poorly known animal by providing an up-to-date synthesis of red panda data gathered from captivity, field studies and the laboratory as well as from culture and tradition, and to publish this in a single volume which will provide the first comprehensive account of the red panda.

The history of the red panda in western science begins in controversy; the man who is generally acknowledged as the first person to describe the species was not accorded the usual honour of naming it. The discovery of the red panda is attributed to the Englishman, Major-General Thomas Hardwicke, who served in the Indian Service. Hardwicke was a keen naturalist who explored the areas where he was stationed. On 6 November 1821 (four years before the Cuvier publication), Hardwicke presented a paper to the Linnaean Society of London called “Description of a New Genus of the Class Mammalia, from the Himalayan Chain of Hills between Nepaul and the Snowy Mountains”. Unfortunately, Hardwicke’s paper did not go to press until some six years later. In the interim, Frederic Cuvier, son of the famous French zoologist Georges Cuvier, published the first written description of the red panda. As this latter account, which went to press in 1825, was the first published report of an animal new to science, it was Cuvier, not Hardwicke, who had the honour of giving the panda its scientific name. The name he chose was Ailurus fulgens meaning shining or fire-coloured cat (“ Ailurus, à cause de sa ressemblance extérieure avec le Chat, et pour nom spécifique celui de Fulgens, à cause du brilliant de ses couleurs”, Ailurus because of its external resemblance to the cat and fulgens because of its brilliant colours) [6]. Cuvier’s description of the panda was based on a few remains (skin, paws, incomplete jaw bones and teeth), which had arrived in Europe, together with a general description of its appearance provided by his son-in-law, Alfred du Vaucel. Even from this limited material, Cuvier realized that he was dealing with a unique species that was not represented in the collections of the Paris Natural History Museum.

Hardwicke also provided a detailed account of the red panda describing its coat as “a beautiful fulvous brown colour which on the back becomes lighter and assumes a golden hue” [3]. He also deduced that, due to its striking peculiarities, it must belong to a new genus. In particular, he referred to the singular structure of its teeth. Hardwicke reported that red pandas lived near rivers and mountain torrents, that they spent much of their time in trees and that they fed on birds and small mammals. He also noted that they were referred to by the local people as Wha or Chitwa because of their vocalizations. Although Hardwicke’s paper was not published until 1827, two years after Cuvier’s publication, the then secretary of the prestigious Linnean Society felt that Hardwicke’s description was too important to be omitted from the Transactions of the Society.

However, the story around the discovery of the red panda does not end there; it has been proposed that the first European to see a red panda in the wild did so before either Hardwicke or Cuvier published their descriptions. A Dane, the botanist Nathaniel Wallich, who was director of the East India Company’s Botanical Garden in Calcutta, made a number of collecting trips to the mountainous regions of Nepal in the early 19th century. He is known to have brought back a number of animals from this region for both General Hardwicke and Alfred du Vaucel. Indeed, as Morris and Morris have suggested, although there is no record of the event, it could well be that Wallich in fact provided the red panda specimens used by Cuvier and/or Hardwicke [1].

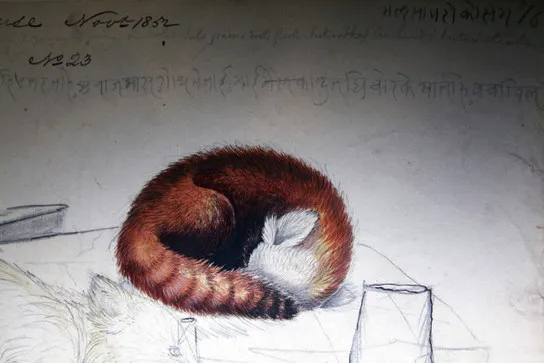

For many years, the red panda remained known only from skins. It was some 20 years before another English naturalist eventually took an interest in this creature. Brian Houghton Hodgson was a retired Indian civil servant who moved to the high mountains of Sikkim where he lived for 13 years. He was a well-known naturalist who published nearly 130 papers on the mammals and birds of the Himalayan region in addition to numerous papers on physical geography, ethnography and ethnology of the region. In 1847, Hodgson published his work on the red panda in the Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal [7]. This paper tells us much about the red panda or, as he refers to it, the Wah. Hodgson was also a good artist and two of his images of the red panda are presented in Figures 1.3 and 1.4. Much of the information that Hodgson published on the red panda was, until comparatively recently, all we knew about this species in the wild, much of it still remains undisputed. He reported that red pandas could be found in the northern parts of the central mountain region and all the forested areas of the “juxta nivean” or Cachar region between the altitudes of 7000 and 13 000 feet (2500 and 4500 metres) and emphasized that they did not live in the snows. He knew that wahs were arboreal, although they descended to the ground to feed. He said no other quadruped could surpass the wah as a tree-climber and observed how they would “climb steadily and firmly, upwards and downwards without any necessity for turning back on themselves”, i.e. head first. He also noted that they were plantigrade and moved awkwardly “but without special embarrassment” when on the ground and, when they needed to travel faster, they moved with a series of bounds.

Hodgson knew a lot about the red panda’s biology. He described their diet as consisting of fruits, tuberous roots, thick bamboo sprouts, acorns, beechmast and eggs. Actually, Hodgson believed that eggs were the only animal material eaten by red pandas and he doubted that they would eat any meat despite being assured to the contrary. Interestingly, he also reported that he had never seen a wah using its hands when eating despite the fact that red pandas regularly hold bamboo in their forepaws to feed using their false thumb to help them get a good grip of the stems. Hodgson also observed that wahs love to eat milk and ghee (the clarified butter used in Indian cuisine) and reported that they would raid remote dairies and cowsheds to steal these delicacies. One may wonder if this report is the source for including milk in so many zoo diets for red pandas. Hodgson also realized that red pandas were crepuscular rather than truly nocturnal and said they slept in the daytime “curled like dogs or cats with the tail over the eyes to exclude light”. In his view, red pandas were monogamous and bred only once each year. He noted that the young remained with their family until the next birth at which time the mother would drive them away, that births occurred in spring or early summer, that the average litter size was two with one cub usually being bigger than the other and that this size difference was not related to gender. Interestingly, Hodgson noted that the wah he was discussing originated from Assam and Sikkim, and that he thought it was different to the panda which had been described by Cuvier, which he supposed had originated from Bhutan. Hodgson, therefore, provided a full description of his wha with the suggested name of Ailurus ochraceus or the Nepalese Ailurus that he describes as being a “deep ochreous red” with jet-black belly, ears, limbs and tail tip.

In fact, the existence of a second form of wah or panda was confirmed in 1902 in a publication by Oldfield Thomas who described and named this Szechuan panda on the basis of a specimen donated to the Natural History Museum of London by Mr F.W. Styan [8]. Thomas reported a difference in colour between this red panda and the one described by Cuvier but said that he suspected that the colours were variable, even in the Himalayan form. The main difference Thomas found between the two forms was one of size; he reported, for example, that the skull of the Chinese form was significantly larger than that of the Himalayan form. In this publication, Thomas states that he does not consider the Chinese specimen to belong to a separate species as he felt that there might be various intervening forms that had not been found. However, by 1922, Thomas seems to have revised his opinion. In a second publication on the Chinese red panda, this time based on specimens originating from northern Yunnan and north-eastern Burma, he reports that, while the examples originating from these regions are similar to each other, there are cle...