![]()

1 Introducing the chiefs of staff

AT THE HEART OF government are people employed to help prime ministers do their job. Perhaps the most crucial appointment is the prime minister’s chief of staff (CoS). This person sets the tone of how the Prime Minister’s Office (PMO) runs and how their boss works. The CoS has a broad remit, but there is no job description. They support both the person who is prime minister and the position that they hold. They run the private office, which now has more than fifty staff and operates twenty-four hours a day every day of the year. The CoS tries to ensure the prime minister sets priorities and sticks to them, notwithstanding that crises and unexpected events will inevitably demand their time and attention. They help the prime minister to control the agenda, coordinate policy initiatives and maintain effective relation ships with the cabinet, the ministry, the party room, the media and the public service.

The chief of staff’s work spans being sensitive to their boss’s most basic needs such as feeding, watering and getting enough sleep. At the same time they are the prime minister’s gatekeeper—filtering who they see and how and where they spend their time. It is hard to find out who the CoS are and what they do. It is a difficult and often fruitless search on official Australian government websites to find any information about the prime minister’s CoS or their work. Only twenty-six people have held this position since Whitlam formalised the office in 1972, but our research ends with the twenty-fourth, Ben Hubbard (see pp. 10–11). Evocative phrases are used to describe them such as ‘the hidden face of power’, and ‘the people who live in the dark’. Such phrases mislead. Their world has changed. They no longer lurk in the background. They are public figures subject to commentary and often to criticism in the media.

Nowhere has this been more apparent than with Australia’s current Prime Minister’s CoS, Peta Credlin. Within months of becoming prime minister, Tony Abbott became all too aware of the perils arising from the visibility of his ‘political gatekeeper’. Persistent rumblings became a crescendo of complaint about the working of his office and his high-profile CoS. Within three months of winning office, the press gallery feasted on reports that Credlin had berated Immigration Minister Scott Morrison over his poor performance at a media conference. Queensland Senator Ian Macdonald (a shadow minister who described being left out of Abbott’s ministry as ‘the worst day of his life’) accused the PMO of exercising ‘obsessive centralised control’. Unhelpfully for Abbott, a number of disgruntled (and not surprisingly, unnamed) Coalition MPs weighed in to express ‘private concerns’ about the behaviour of ‘unelected advisers’, notably Credlin. The Prime Minister was forced to defend his staffers, telling journalists ‘Decisions made by my chief of staff and my office have my full backing and authority’. Abbott calls Credlin, who has worked for him since 2009 and was CoS to Opposition leaders Brendan Nelson and Malcolm Turnbull, ‘the force majeure’. But even Abbott’s supporters complain ‘No one person should have that much influence … It’s too close.’ The Prime Minister’s rebuke of internal dissenters was followed by his Finance Minister, Mathias Cormann, who launched a staunch defence of Credlin, calling on her critics to ‘back off’. He argued Credlin had played a central role in Opposition and securing the Coalition’s election victory. ‘She obviously has a very important job at the heart of the government and she will be central to our success.’

Such complaints about the ‘control freakery’ of the CoS and PMO are so common as to be almost routine, particularly during the transition to government. Similar complaints were levelled against the offices of Paul Keating, John Howard, Kevin Rudd and Julia Gillard. Central control over staffing and other appointments, over the timing and scheduling of media appearances and policy announcements are insurance against mistakes and missteps as ministers and ministerial staff seek to cope with the rigours and scrutiny of being in government. If the tone is respectful and the government is going well, most of its members will wear such control. If ministers and elected representatives feel they are not being heard; if they think they are not getting a share of the leader’s time and attention; and if central control becomes entrenched as a governing style, then they push back. Attacks on the CoS and the PMO are proxies for attacks on the leader. The CoS are the lightning rod of discontent for those unwilling to confront the prime minister. They are the ‘shock absorbers’ of prime ministerial frustration and displeasure. They manage conflicts between ministers and their departments and in the party room. And they must do all this without committing the cardinal sin of themselves becoming the story.

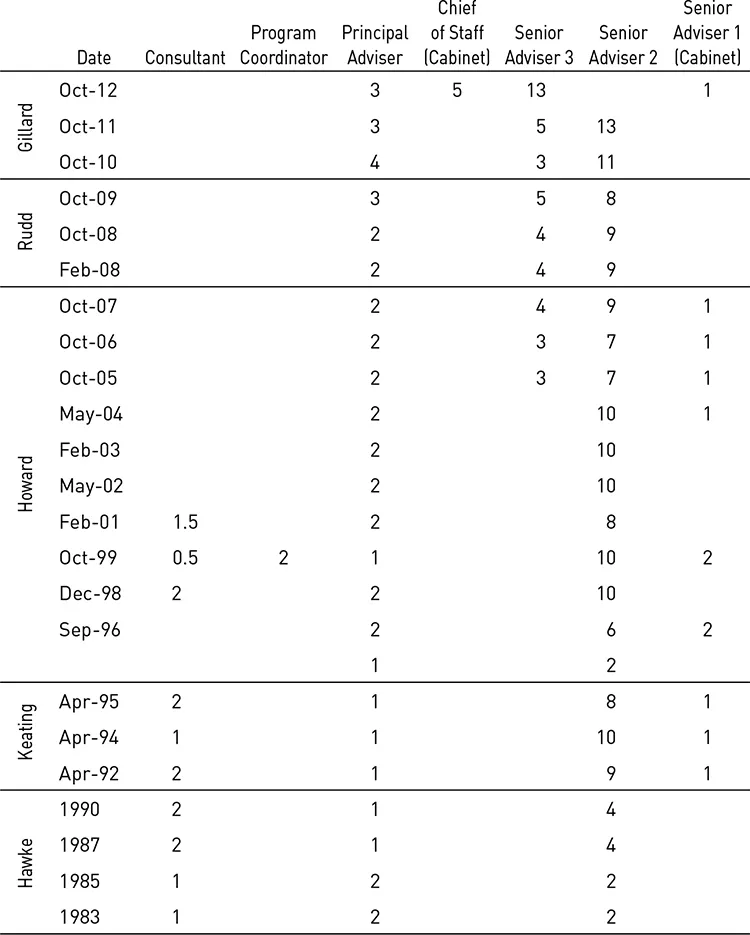

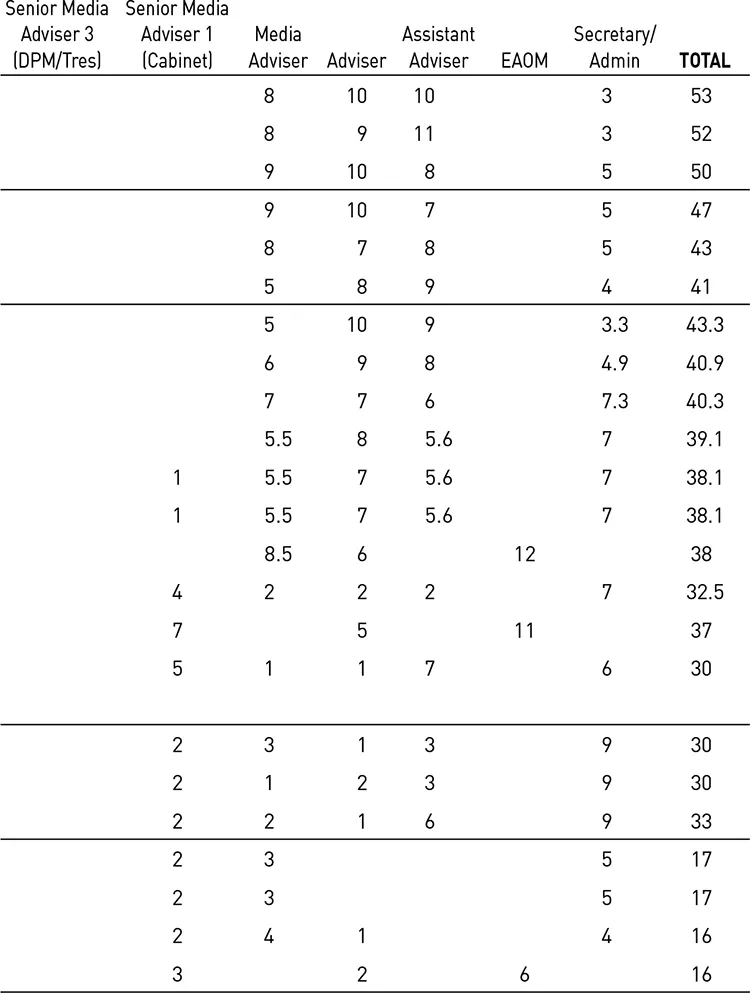

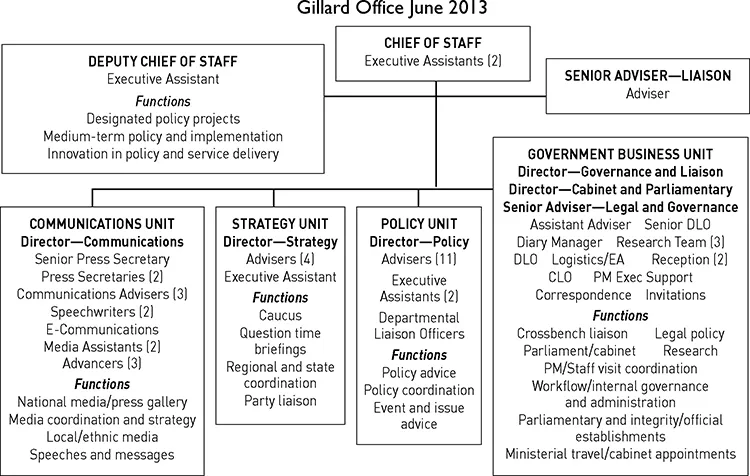

Centralisation is not the only criticism. Much concern is expressed about the growth in political appointments and the expansion of the PMO under recent Australian prime ministers. The table and organisation charts on pp. 6–9 show the growth in both staff numbers and the increasingly diverse responsibilities of the CoS and PMO from 1983–2013. Leaders have been the primary drivers of these changes, but the move to the new Parliament House in 1988 was also decisive. The design provided additional space to accommodate a larger, more functionally specialised prime ministerial support staff. These developments have been essentially bi-partisan. Each prime minister has built on the foundations of their predecessor in fashioning the modern hybrid advisory system that includes a large, active and partisan PMO and non-partisan career officials in the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C).

Jennifer Westacott, Chief Executive of the Business Council of Australia, is one of many commentators concerned about the role and influence of political advisers, particularly in a larger, more specialised PMO. She argues that the authority of the public service ‘has been undermined by political gatekeepers, often with little expertise and no accountability. Australia now has more personal staff per minister than many other comparable countries.’ She recommends that we ‘halve the allocation of personal staff in ministerial offices and establish a mandatory code that prohibits them from directing public servants’ and ‘reinstate the tenure of departmental secretaries’. Former Secretary of the PM&C, Terry Moran also calls for a mandatory code so that ‘political advisers would then be subject to the same accountabilities that apply to public servants’. Former Productivity Commission Chair, Gary Banks, also notes the growth in the number of political staffers, their ‘lack of policy expertise’ and ‘the subtle erosion of the capacity of our most senior public servants to “speak truth to power”’. If accurate, this view of the current state of the PMO would mean The Hollowmen and The Thick of It have ceased to be satire based on grotesques like Tony and Murph or Malcolm Tucker and become descriptions of everyday life in government. Is this fair?

The problem with these several criticisms is that they are based on stereotypes and anecdotes recounted by unnamed sources and not on a systematic and accurate account of the work of the CoS and other political staffers. The critics seek change but never cite specific cases or examples of the problems that demonstrate the need for their proposed reforms.

This account of the CoS’s work is unique because it does not rely on off-the-record briefings. Instead, we report how people who have been there describe the work that supporting prime ministers entails. It is their, not our, view of their work and how they sought to do it.

In our book Lessons in Governing we traced the development and evolution of the position of the CoS from its tentative beginnings under the Whitlam government to the present day. We showed how over the forty years of its formal development, the position of the prime minister’s CoS has evolved to become central to the exercise of political leadership and a necessary, but not sufficient, condition for prime ministerial effectiveness. We described the people, the job and its dilemmas and assess the motives underpinning successive prime ministers’ drive for greater control over their advisory and support systems, and the consequences that have flowed from their determination to decide the membership of key central government networks.

Here in The Gatekeepers we distill lessons that CoS say they learned from their time in the position. We ask what we can learn from CoS about what to do and what not to do, about how to do it and how not to do it. As authors we do not presume to know better than the practitioners.

Instead, we aim to draw together, to systematise, CoS views about the lessons they would pass on to their successors. We seek to do so in their words, using the stories they told us and each other about to how to do the job.

We are able to describe the work of the CoS because, in late 2009, Anne Tiernan and Patrick Weller held two closed, round-table workshop discussions with CoS whose experience spanned governments from Fraser to Rudd. Each session aimed to elicit participants’ views on: the development and evolution of the job of CoS; how different individuals approached the task of working with the prime minister; the key duties and responsibilities that they performed; the challenges confronting the CoS at different stages of the governing cycle and lessons that might be ‘passed on’ to their successors.

Seven CoS attended the first session in Canberra on 1 September 2009. These were Dale Budd and David Kemp (Fraser), Graham Evans (Hawke), Don Russell and Geoff Walsh (Ke...