![]()

CHAPTER 1

The History of Mental Illness and its Treatment

Steady progress has been made towards scientific enlightenment and better treatment for the mentally ill. However, insights from the past remain useful. While psychiatry’s past is littered with the corpses of ineffective, and at times hazardous, treatments, certain progressive social approaches to mental illness may have been lost sight of and need revisiting. Thus, critical appraisal of contemporary enthusiasms is again demonstrated to be a useful function of the study of history. In the words of the philosopher George Santayana, ‘Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it’.

Attempts to understand and treat the mentally ill go back centuries. Name changes reflect the diverse ways in which mental illness has been regarded. For example, ‘lunacy’ is derived from the belief that people’s mental states deteriorated at full moon; ‘insanity’ from the Latin insanus, meaning unsound mind; and ‘psychiatric’ from the Greek words for soul, psyche, and healing, iatreia.

Possibly the earliest account of a disturbed mind is recorded in the Ayur Veda, a 3500-year-old Hindu text. A man is described as ‘gluttonous, filthy, walks naked, has lost his memory and moves about in an uneasy manner’. In the first Book of Samuel we read that King David simulated madness in order to gain safety: ‘And he changed his behaviour … and feigned himself mad in their hands, and scrabbled on the doors of the gate, and let his spittle fall down upon his beard’. In the Book of Daniel we find a vivid description of King Nebuchadnezzar’s mental state: ‘And he was driven from men, and did eat grass as oxen, and his body was wet with the dew of heaven, till his hairs were grown like eagles’ feathers, and his nails like birds’ claws’.

The ancient Greeks went beyond mere description of madness. Their explanations of the causes centred about an imbalance of bodily humours or fluids. Hippocrates, in the fourth century BC, viewed it this way, but also invoked environmental, physical and emotional causal factors. The Greek physician Galen, who practised in Rome 600 years later, persisted with the concept of fluid imbalance, postulating that depression was caused by an excess of black bile (hence the term ‘melancholia’, from melan, black, and khole, bile), though he also took emotional influences such as erotic desire into account. Modern psychiatry conceptualises disturbances of mood in strikingly similar ways to those of the ancients. Indeed the term ‘melancholic features’ resurfaced in the twentieth century to cover the biological changes seen in depression.

During the Middle Ages, the monasteries preserved the view of madness as an illness and of those afflicted as blameless. At the same time, the more sinister belief that the principal cause of the troubled mind was possession by the devil prevailed. Sufferers were taken to sanctioned healers, usually priests or shamans (a practice still carried out today in some cultures).

People who failed to respond to such routine treatment might then seek out a celebrated expert. The case of Hwaetred, a young man who became tormented by an ‘evil spirit’, is a clear example. So terrible was his madness that he attacked others with his teeth; when men tried to restrain him, he snatched up an axe and killed three of them. Taken to several sacred shrines, he obtained no relief. His despairing parents then heard of Guthlac, a monk who lived a hermit life north of Cambridge. After three days of prayer and fasting Hwaetred was purportedly cured.

Sin was rarely seen as causing mental illness. Rather, it was a visitation from without, affecting even righteous people. A particularly harrowing period was the seventeenth century, when religiously inspired persecution of the mentally ill was justified by the clerical hierarchy, who designated them as witches. Fortunately, this coincided with the medical profession’s claim to exclusive practice of the healing arts, such as they were, and its withdrawal from former links with the priesthood. A new fairness in treatment of deranged people resulted both from the church’s emphasis on charity and medicine’s growing agreement that the cause of insanity was physically based.

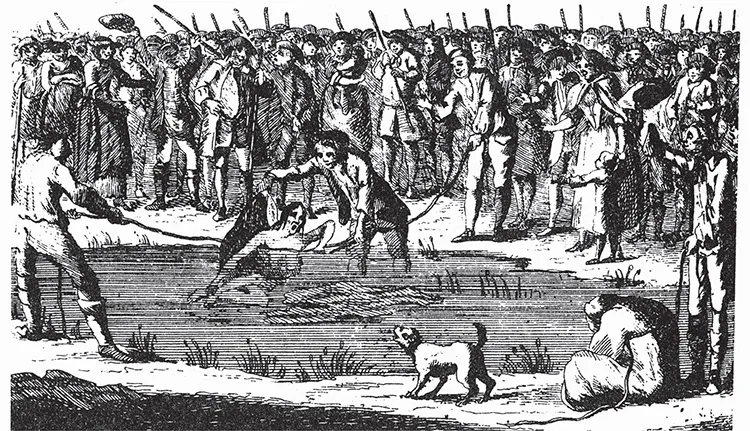

Life before the Industrial Revolution has been portrayed as one of tranquillity, the countryside supposedly scattered with picturesque villages whose inhabitants tilled the fields, celebrated festivals and cared cooperatively for one another. The reality was otherwise. Thomas Hobbes, the social philosopher, described their lives as ‘solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short’. The insane were depicted as ‘miserable individuals, wandering around in village and in forest, taken from shrine to shrine, sometimes tied up when they became too violent’.

The late eighteenth century was a watershed in the history of psychiatry. The insanity of England’s King George III revealed society’s ambivalence to the mentally ill (vividly captured in the film The Madness of King George). In France, Philippe Pinel released the chains that had fettered the ‘lunatic’ for centuries, ushering in an unprecedented phase of benevolent institutional care. Moral therapy was the most significant advance of this era. It supplanted earlier physical treatments such as purging, bleeding and dunking in cold water. Moral therapy worked instead on the intellect and emotions, and was designed to achieve internal self-restraint and mental harmony. The approach was taken up with fervour by the Quakers who established the York Retreat; the humane movement was soon championed in the United States.

Literary descriptions of mental illness

An evocative description of mental illness by Honoré de Balzac appears in his novel Louis Lambert, published in 1832. The main character, a highly intelligent young man, becomes infatuated with a childhood sweetheart but once married plunges into a world of insanity. The narrator, a childhood friend of Louis, notes on seeing him:

… his body seemed to bend beneath the weight of his bowed head. His hair, which was as long as a woman’s, fell over his shoulders and surrounded his face, which was perfectly white. He constantly rubbed one of his legs against the other with an automatic movement which nothing could check, and the continual rubbing of the two bones made a ghastly noise. Beside him was a mattress of moss, laid on a board. He was a remnant of vitality rescued from the grave, a sort of conquest of life over death, or of death over life. Suddenly Louis ceased to rub his legs together and said slowly, ‘The Angels are white’.

Nikolai Gogol, the Russian novelist, published Diary of a Madman around the same time. Gogol himself was destined to succumb to what was probably severe depression, manifesting as pervasive guilt, social withdrawal, despair and finally death by self-starvation. The story paints a frenzied picture of madness and the final plea is heart-rending: ‘Mummy, save your poor son! Shed a tear on his poor battered head and look how they are tormenting him! Press your orphan boy to your breast! There is no place for him on earth! He is persecuted! Mummy, have pity on your sick little child!’

Guy de Maupassant, the French writer, recorded the essence of the disordered mind in a short story, The Horla, offering this vivid description:

I ask myself whether I am mad … doubts as to my own sanity arose in me, not vague doubts, such I have had hitherto, but precise and absolute doubts. I have seen mad people and I have known some who were quite intelligent, lucid, even clear sighted in every concern of life, except at one point. They could speak clearly, readily, profoundly, on everything, till their thoughts were caught in the breakers of their delusions and went to pieces. There, they were dispersed and swamped in that furious sea of fogs and squalls which is called madness … Was it not possible that one of the imperceptible keys of the cerebral fingerboard had been paralysed in me? … By degrees however, an inexplicable feeling of discomfort seized me. It seemed to me as if some unknown force were numbing and stopping me, preventing me from going further and calling me back.

Eventually the narrator comes to believe that he can fend off his persecutor only by setting fire to his house. But his torment persists to the final lines: ‘No—no—there is no doubt about it—he is not dead. Then—then—I suppose I must kill myself!’

The era of the asylum and advent of physical treatments

The sheer numbers of mentally ill people in burgeoning urban slums demanded action. An institutional solution emerged. Asylums (from the Greek word meaning refuge) were built in rural settings with the best of intentions, planned to be havens in which patients would receive humane care. In the serenity of the countryside, and through carrying out undemanding tasks, they could be distracted from their internal torment and find dignity far from the madding crowd. Daniel Defoe, the English writer, remained unconvinced: ‘This is the height of barbarity and injustice in a Christian country; it is a clandestine Inquisition, nay worse’.

Though conceived in a spirit of optimism, asylums tended to deteriorate into centres of hopelessness and demoralisation. They soon became overcrowded dumps. Institutions originally built for a few hundred people were soon holding thousands. Very few residents were discharged; many stayed for decades. Brutal oppression replaced anything that might have resembled treatment; malnutrition and infectious disease became rife. In the grim environment, people were shut away and forgotten. Family contacts were often lost, especially as the asylum was frequently at a distance from the patient’s home. Out of sight and out of mind, a loss of public interest and political neglect became the norms. A fascinating exception is the York Retreat in England, established by the local Quaker community.

The brooding building on the hill came to symbolise the fear of mental illness and the stigma with which it remains associated—alas, even to the present time. By the mid-nineteenth century, critics were voicing concerns that asylums had evolved into human warehouses in which mental illness inevitably became irreversible. The combination of powerless patients, hospitals run more for the convenience of staff than for the benefit of the sick, inadequate inspection by state bodies and lack of resources led at times to quite disgraceful conditions. Unwittingly, the spread of asylums also triggered the movement of psychiatry away from the mainstream of medicine. This regrettable divorce was reflected in the term ‘alienist’ for doctors who practised in the asylums. Attendants and medical staff were also often cut off from the rest of society in that they lived with their families in the hospital grounds.

The conditions are evocatively described in Henry Handel Richardson’s Australian novel, The Fortunes of Richard Mahony. We read of Richard’s decline, probably from neurosyphilis, which at that time afflicted a large proportion of mental patients. Towards the end of the novel his wife comes to visit him in the asylum:

She hung her head, holding tight … to the clasp of her sealskin bag, while the warder told the tale of Richard’s misdeeds. 97B was, he declared, not only disobedient and disorderly, he was extremely abusive, dirty in his habits … would neither sleep himself at night nor let other people sleep, also he refused to wash himself, or to eat his food … But she had to keep a grip on her mind to hinder it from following the picture up: Richard, forced by this burly brute to grope on the floor for his spilt food, to scrape it together and either eat it or have it thrust down his throat … she had heard from Richard about the means used to quell and break the spirits of refractory lunatics … There was not only feeding by force, the straitjacket, the padded cell. There were drugs and injections, given to keep a patient quiet and ensure his warders their freedom: doses of castor oil so powerful that the unhappy wretch into whom they were poured was rendered bedridden, griped, thoroughly ill.

Although such a decline was often the result of years of confinement, the concept of a degenerative process in the brain became widely accepted as a likely explanation and gained added impetus from the rise of pathology as a branch of medical science. The search for causes of mental illness in the brain proved fruitful in some areas, especially in identifying neurosyphilis and the neuropathology of Alzheimer’s dementia.

So compelling was the organic paradigm that all major forms of mental illness were assumed to be caused by a degenerative brain process. Thus, when the clinical syndrome of dementia praecox was mapped out through the careful scientific work of the great German psychiatrist Emil Kraepelin, it was assumed that it also had a degenerative basis and that the outcome was inevitable decline. So too with the Swiss psychiatrist Eugen Bleuler, who in 1911 renamed dementia praecox with the term we use today, schizophrenia. Though most understanding towards his patients, Bleuler propagated the idea that they could never fully recover. This was undoubtedly related to the fact that many of his patients were hospitalised for decades without effective treatment.

Great and desperate cures

In the asylum, too, psychiatry turned into a medical discipline. The accumulation of thousands of patients provided the first opportunity to study mental illness systematically. But the priority was the suffering of overwhelming numbers of disturbed patients. Psychiatrists grasped for ‘great and desperate cures’. Henry Rollin, an English psychiatrist and medical historian, captures the intense zeal:

The physical treatment of the frankly psychotic during these centuries makes spine-chilling reading. Evacuation by vomiting, purgatives, sweating, blisters and bleeding were considered essential … There was indeed no insult to the human body, no trauma, no indignity which was not at one time or other piously prescribed for the unfortunate victim.

Treatments were sometimes based on rational grounds. Malaria therapy, for instance, was launched as a treatment for syphilis affecting the brain by the Viennese psychiatrist Julius von Wagner-Jauregg in 1917, earning him a Nobel Prize ten years later. The rationale for inducing a high fever using the malarial parasite was the heat sensitivity of the spirochete that caused neurosyphilis. Von Wagner-Jauregg may have had a point; substantial improvement occurred in the nine cases he reported on a year later. But the hope that it would be equally effective for other forms of psychosis was soon dashed. The wished-for panacea was not to be. In any event, malarial therapy was hazardous and difficult to apply.

Insulin coma therapy was introduced by Manfred Sakel in the 1930s in Vienna and was soon being used in many countries to treat schizophrenia. An insulin injection was administered six days a week for several weeks, producing a state of light coma lasting about an hour, because of reduced glucose reaching the brain. Many years later, an investigation carried out in the Institute of Psychiatry in London, a leading research centre at the time, showed conclusively that the coma itself was of no therapeutic value. The benefits noted were probably attributable to the conscientious attention given to the patient by dedicated staff over an extended period.

The first widely available and effective physical treatments for mental illness were developed in the asylum. The discovery in 1938 of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) by Cerletti and Bini, two Italian psychiatrists, led to a dramatically effective treatment for people with severe depression. ECT was eagerly adopted in practice but its history illustrates a typical pattern of treatment in psychiatry, where unbridled early enthusiasm is later tempered by a protracted process of scientific evaluation. Exactly the same can be said of psychosurgery—or surgical procedures—on the brain to modify psychiatric symptoms. This was pioneered in 1936 by a Portuguese neurologist, Egas...