![]()

1 The Anglican Ascendancy 1788–1835

Brian Fletcher

Colonial Chaplaincy

The history of the Anglican church in Australia forms part of a broader process which transformed the nationally based Church of England into a global communion. Elsewhere expansion was associated with the growth of empire, but in Australia the church originated as part of the English penal system. It began its existence in January 1788 with the arrival at Botany Bay of a thousand or so convicts, soldiers and civil officials. Among them was the Reverend Richard Johnson in whom the church was personified. Subsequently, the church spread its influence not only through New South Wales but also to Van Diemen’s Land, Western Australia and South Australia, the last two free colonies which had made limited progress by 1836. Western Australia was a speculative venture and it was only the chance shipwreck in 1829 of Archdeacon Thomas Hobbes Scott, en route from Sydney to England, that brought the colonists their first clergyman. The few who followed struggled for survival in a thinly populated and poorly planned colony that was soon in difficulties. South Australia, by contrast, was settled partly for religious reasons, although not of a kind to benefit Anglicans. The driving force came from Nonconformists who sought equality for all churches and opposed state aid. Anglicans lacked strong backing in what has been referred to as the ‘Paradise of Dissent’ and were denied the advantages enjoyed in other parts of Australia.

Rather different was the situation in eastern Australia where the church was brought into being by an act of state. The decision to send a clergyman to Botany Bay in 1788 formed one element in the British government’s plans for a settlement that was largely, although by no means exclusively, penal in character and intent. As the instructions to the first and subsequent governors made clear, religion went hand in hand with the maintenance of good order. Christian teaching, with its emphasis on the need to lead a moral life and the calling of sinners to repentance, provided a means by which convicts could be controlled and perhaps even reformed. This was important, not only in itself but also as a way of securing a compliant workforce necessary if the settlement was to function cheaply and effectively. The fact that convicts were expected to remain in the colony after completing their sentences made it even more desirable for them to be purged of their criminal tendencies. The Church of England, as the only branch of the Christian faith officially recognised in England, was the instrument naturally chosen to implement the government’s objectives. Clergy could convey the appropriate message and set an example through the purity of their own lives. In England they customarily served as magistrates and in this capacity could readily assist the hard-pressed civil administration of New South Wales. Similar objectives were later evident in the settlement of Van Diemen’s Land where, in 1803, convicts and soldiers were sent to forestall a rumoured French occupation. No chaplain accompanied the expedition to the north of the island. One did sail from England with the party commanded by David Collins, which left for Hobart after the original destination of Port Phillip was found unsuitable.

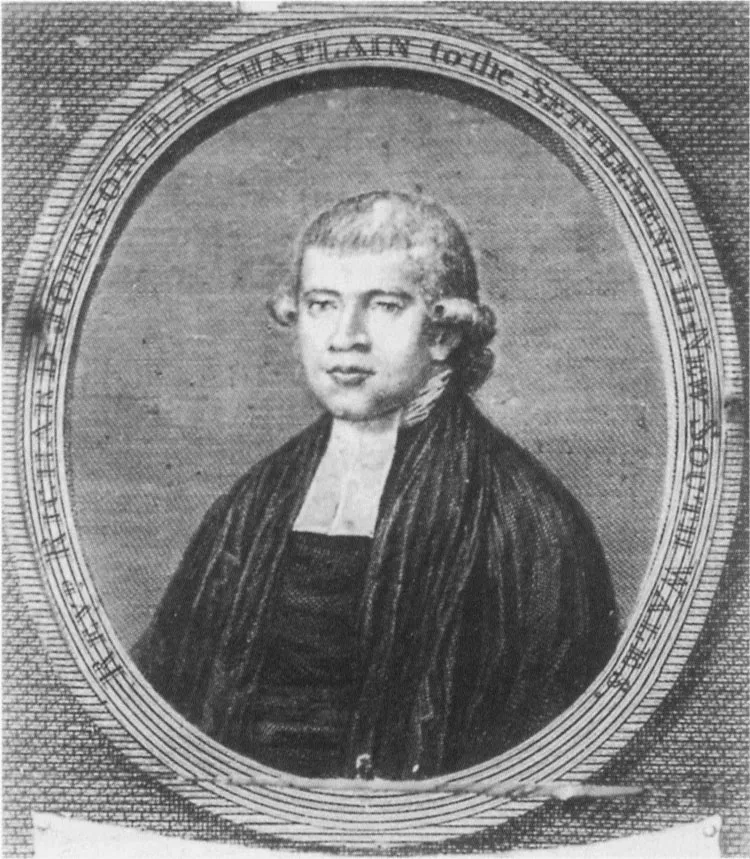

Although practical considerations deriving from the peculiarities of the new settlements influenced the government, forces that had their roots in the Church of England were also at work. Its leaders were little interested in colonial churches, concentrating instead on the national scene where social changes resulting from the industrial revolution were creating problems. The plight of transported felons came low on the order of priorities not only for the church but also for missionary bodies such as the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel (SPG). Although interested in the new penal colony, SPG directed its main attention elsewhere. More responsive were the Evangelicals who formed part of the eighteenth-century religious revival spearheaded by the Wesleyan Methodists. Whereas Wesley and his followers left the Established church, evangelicals remained loyal and concentrated on overcoming the spiritual torpor into which they wrongly believed it had sunk. They attracted leading public figures such as William Wilberforce, the Yorkshire parliamentarian and friend of Prime Minister William Pitt, and espoused causes such as the abolition of the slave trade and prison reform. Wilberforce took a personal interest in the Botany Bay project. The Eclectic Society, in which he played a leading role, nominated Richard Johnson as chaplain to New South Wales.

Until late in the governorship (1809–21) of Lachlan Macquarie, the Anglican church was the only denomination to receive official recognition and support. The laws directed against Roman Catholics in England since the Reformation applied also in the eastern Australian colonies. Reinforcing them was concern that priests might become a focus for discontent among the Irish convicts. Only three priests arrived before 1820: Fathers Dixon and Harold as political offenders and Father O’Flynn of his own volition. The first two stayed from 1803 until 1805, while the third was deported shortly after arriving in 1817. The legal restraints applying to Roman Catholics in England extended to Nonconformists but were administered more leniently. The government did not prevent Protestant ministers sailing to the antipodes but offered them no assistance. A handful of London Missionary Society refugees arrived from Tahiti in 1798. There were also two Presbyterians, variously labelled catechists or elders. Only the Methodists sent clergy, beginning in 1815 with the Reverend Samuel Leigh, the first of four to arrive by 1820. This denomination, along with others outside the Anglican fold, had lay rather than clerical beginnings.

The Anglican church existed before the 1820s as the arm of a government that provided financial backing and practical support. Twelve chaplains arrived on the mainland before 1821 and two in Van Diemen’s Land. All received land for their own use, enabling them to attain a standard of living appropriate to their social status. Land was also made available for churches, schoolrooms and parsonages. Convict labour and other assistance was offered to help construct necessary buildings, and stipends were paid from the British exchequer. The clergy were essentially members of the civil establishment and the terms of their appointment subjected them to the jurisdiction of governors. Initially under the episcopal supervision of the Bishop of London, they were transferred in 1814 to the newly created See of Calcutta. Distance, the burdens of office and limits on their powers meant, however, that neither bishop was in a position to influence developments in New South Wales.

All of the governors were expected to worship in the Church of England; yet the strength of their attachment varied, as indeed did the circumstances they faced as administrators. The first governor, Arthur Phillip, did what he could to assist the Reverend Richard Johnson. Resources, however, were scarce and priority had to be given to taming an unfamiliar and inhospitable land. The military officers who took command after Phillip’s departure favoured the New South Wales Corps chaplain, James Bain, and placed obstacles in Johnson’s way. Matters improved thereafter. Governor John Hunter had once contemplated ordination in the Church of Scotland and displayed a keen interest in the Anglican church. So too did his successors, Philip Gidley King and William Bligh, whose overthrow in the ‘Rum Rebellion’ of 26 January 1808 created problems for Henry Fulton, the only Anglican clergyman then present. He was suspended for his loyalty to the Governor. Fortunately a second chaplain, William Cowper, arrived in the midst of the crisis. In the interests of the church he kept clear of the opposing factions.

Fulton was restored following the arrival of Governor Macquarie, a man of strong religious convictions, raised in the Church of Scotland. Autocratic by temperament and training, he imposed his wishes on those under his command and rode roughshod over any who stood in his way. Inevitably his behaviour, combined as it was with the adoption of controversial policies, provoked a reaction, not least from the Reverend Samuel Marsden, who had arrived in 1794 as assistant to Johnson. A staunch defender of the faith, Marsden was also a leading opponent of Macquarie’s decision to treat emancipists as the equals of free colonists and appoint them to responsible positions in the public service and judiciary. He incurred the Governor’s anger for refusing to serve on the bench with such men and for resisting his request to read government orders from the pulpit. Macquarie described him as one ‘much tinctured with Methodism’ and included him among those he accused of undermining his administration. The Governor was also critical of Van Diemen’s Land’s only chaplain, the Reverend Robert Knopwood, a controversial but well-connected Cambridge graduate who mixed easily with local administrators and in Hobart society.

Overall, the relationship the church enjoyed with the state brought considerable advantage. Admittedly, the first church, a modest and unpretentious wattle and daub building, constructed in Sydney and named after the first governor, took some five years to materialise and was completed largely through the personal efforts of Richard Johnson. Destroyed by arson in 1798 it was not replaced for another three years. The new church was a more durable stone building complete with a circular tower. Meanwhile a church of better proportions, named St John after the second governor, had been constructed at nearby Parramatta. As settlement spread and new townships were founded, the number of places of worship grew. In Sydney during 1819 foundation stones were laid for the churches of St James and St Andrew. Macquarie also ordered work to commence on St Luke’s and St Matthew’s at Liverpool and Windsor. All were structures of architectural merit inspired by Macquarie’s plans to beautify the colony’s townships and leave permanent memorials to his own vision. They were also a tribute to his emancipist architect, Francis Greenway, an Anglican who saw himself as an agent of the divine ‘architect of the universe’. At the penal settlement of Newcastle, Christ Church, designed and built by the convict John Clohasy on instructions from Captain Wallis, the commandant, was opened in January 1817. In Hobart, where a gale had destroyed the first church, a new building bearing the Christian name of the commandant, David Collins, was ready for worship although without windows in 1819.

Church and Society

One reason behind the construction of churches was the need to find places of worship for the growing number of convicts. The penal settlement took the form of a prison farm rather than a walled gaol. The convicts were punished not through incarceration but by being employed either on public works projects or by private settlers. Sunday worship conducted by Anglican chaplains was obligatory for all, regardless of creed, but the extent to which orders were enforced and obeyed varied from one administration to another. Much of the clergy’s time was spent preaching to the convicts, conducting rites of passage, engaging in pastoral work and, to a less extent, attending executions. ‘Yesterday’, complained Marsden, ‘I was in the field assisting in getting my wheat. Today I have been sitting in the civil court hearing complaints of the People. Tomorrow I must ascend the pulpit and preach to my people’. Heavy duties imposed physical strains on men who were not accustomed to such hardships. Although twelve chaplains served on the mainland between 1788 and 1820 they were not all present at the same time. During the first six years Johnson worked alone, apart from James Bain who served only as a military chaplain from 1791 until 1794. Between 1794 and 1809 clergy numbers ranged from one to two, increasing thereafter from four to five. Parish divisions were not yet determined and chaplains had to travel long distances, either on horseback or by boat, preaching at several different locations on the same day either in the open air or in the best available building. Even worse was the situation in Van Diemen’s Land where Robert Knopwood carried responsibility for the whole island until 1818.

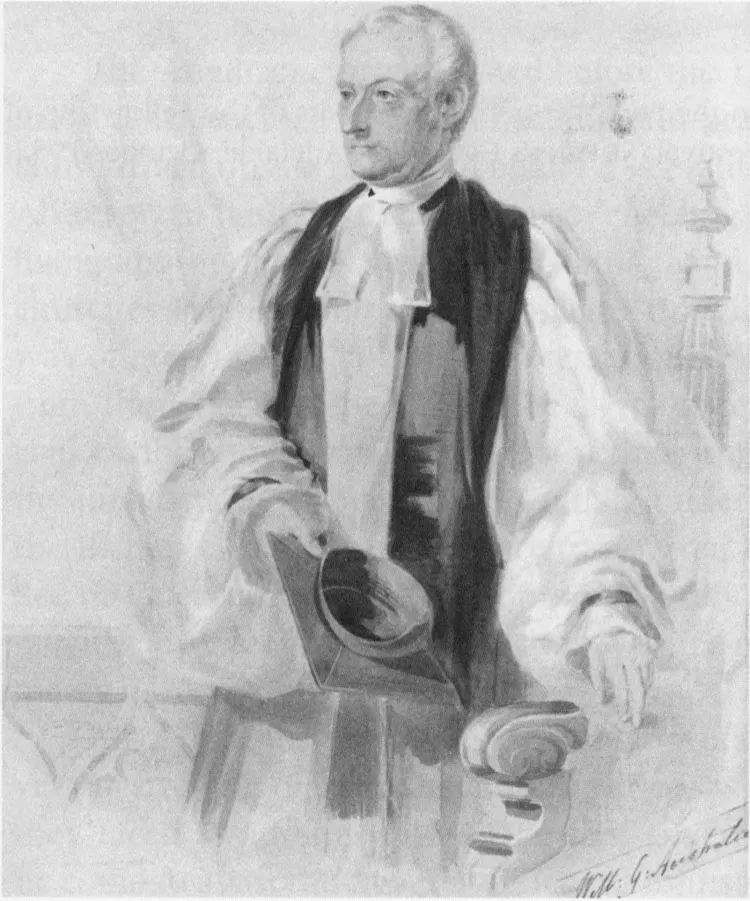

When preaching to convicts the chaplains faced congregations that were far from responsive. While the Irish prisoners resented being forced to attend Anglican services, convicts from other parts of Britain found themselves in surrounds made unfamiliar by their lack of prior acquaintance with the church. They identified the chaplains with the employing class and the regime that had wrenched them from their homeland and subjected them to harsh treatment. Service as magistrates further tainted the clergy, none attracting more opprobrium than Samuel Marsden, ‘the flogging parson’. For their part, the clergy faced formidable challenges made worse by the fact that they had no previous experience of prison farms. Yet all responded positively. With the exception of Henry Fulton, a Church of Ireland minister who was transported for supposed complicity in the 1798 Irish uprising, the early chaplains were products of the evangelical revival. They differed in personality but were united by a strong sense of mission and an inner strength that made them determined to succeed. This was particularly true of Richard Johnson, first in a line of dedicated men which included the controversial, long-serving Samuel Marsden and the Lancashire-born William Cowper, Rector of St Philip’s church in Sydney for over half a century. Important too was Richard Hill, the first incumbent of St James’ church in Sydney where he won praise as a ‘most zealous and reputa...