![]()

1 THE BARRYS

OF COUNTY CORK

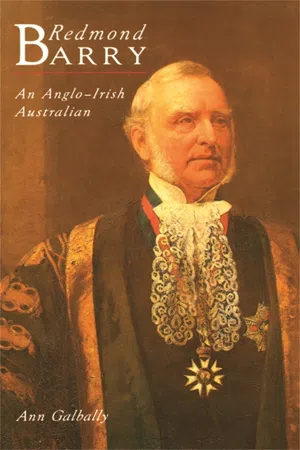

THE FAMILY was an old one and proud of its service to the Crown and the army, local government and law enforcement. Belonging to one but not the grandest of the several branches of the Barrys of County Cork, Redmond Barry could trace his ancestry back to William de Barri of Pembrokeshire, Wales, whose sons took part in the Norman invasion of Ireland of 1169–72. Constructing family trees and researching the Barry genealogy was something of a passion with Redmond Barry and in middle age, when he was trying to inspire a spirit of adventure in his eldest son Nicholas, he wrote to him of ‘our old Norman ancestor’ who had ‘accompanied William 1st’.

In 1180 Robert de Barri was granted three baronies in the Kingdom of Cork by his mother’s brother Robert Fitzstephen to whom Henry II had granted half the Kingdom of Cork three years earlier. The Barrys prospered and multiplied, several branches of the family forming septs in the Irish fashion, the most important of which were Barry Mor and Barry Roe. The baronies of Barrymore and Barryroe were named after these septs—the former flourishing and the latter remaining small due to the vagaries of establishing land ownership in the pre-Elizabethan centuries. By the early fourteenth century the Norman colony was well established in the north-east, in the province of Leinster, around Waterford, Cork, and parts of northern Tipperary. But their attempts to root out the old Irish Brehon law and replace it with English common law had been only partly successful and, prior to the Elizabethan period, English rule had reality only in ‘the Pale’, the core area of influence around Dublin.

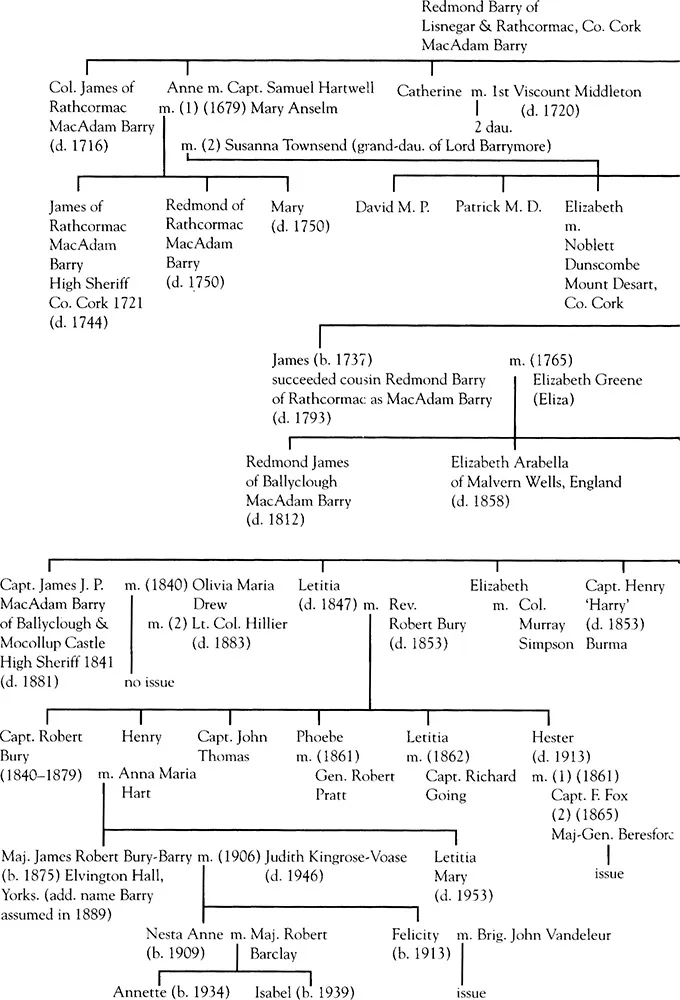

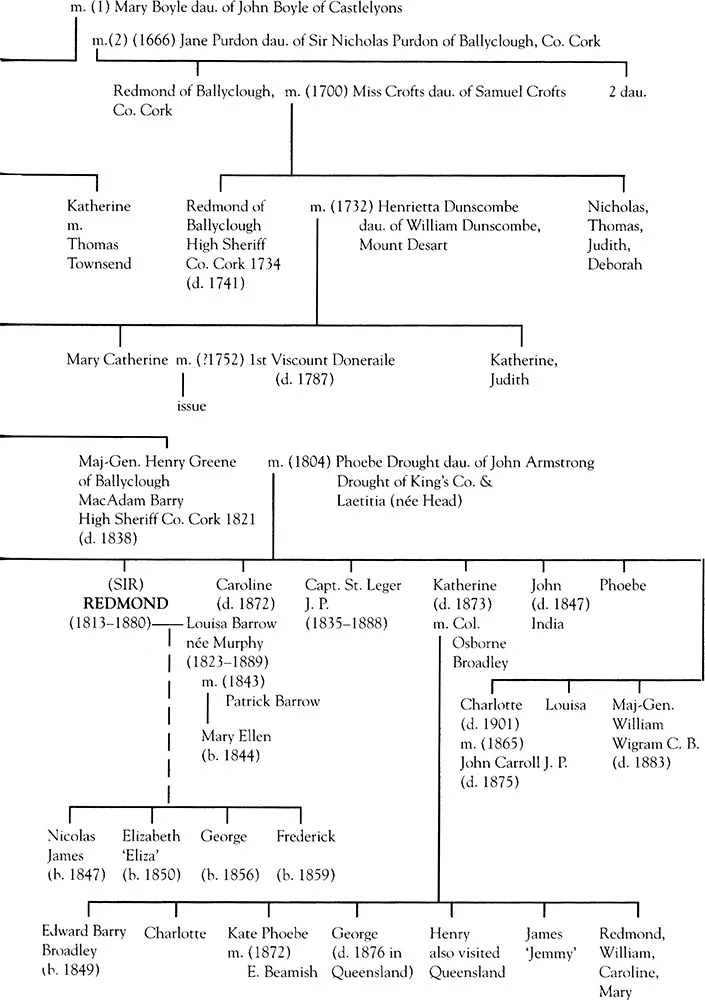

The Barrys of Rathcormac, County Cork—Redmond Barry’s immediate ancestors—further distinguished their branch by adopting the surname MacAdam. This was taken from one Adam Barry, Adam being a common Christian name in Anglo-Norman families with the Mac prefix being the Gaelic form of ‘son of’ In an Irish manner this developed into the title bestowed on the eldest son of the family and leader of the sept, and as a distinguishing connotation in the community.

Barry families with different appellations were to be found all over the barony of Barrymore to the north of Cork city by Elizabethan times, and in the following two centuries various offshoots of the Barry family continued to flourish as landholders. Many suffered under Cromwellian confiscations but not the MacAdam Barrys of Lisnegar, Rathcormac. Although outlawed in 1690, Redmond Barry of Lisnegar managed to keep his estates, and his son James, by judiciously converting to Protestantism and being domiciled in England at the time, managed to have his outlawry reversed.

During the Cromwellian era this same Redmond Barry of Lisnegar was widowed and married a second time to Jane Purdon, only daughter of Sir Nicholas Purdon of Ballyclough, County Cork, in 1666. Ironically Sir Nicholas had earlier purchased the Ballyclough estates after their owner, a certain John Barry, was forced to forfeit under Cromwellian legislation. The son from the first marriage (James) inherited Lisnegar and Rathcormac while Jane Barry’s son inherited Ballyclough. His son, who was our Redmond Barry’s grandfather, inherited the title MacAdam Barry on the death of his cousin Redmond of Rathcormac in 1750.

Due to a family quarrel and the subsequent refusal of any rapprochement between the two parties the valuable Rathcormac property was thrown into Chancery. The Barrys of Ballyclough eventually lost the ensuing litigation and with it most of the Barry estates at Rathcormac on the southern side of the Blackwater River from Ballyclough. Grandfather James Barry made some effort towards redressing this setback in family expectations by marrying, in March 1765, Elizabeth Greene, daughter and co-heir of Abrahame Greene of Ballymachree, County Limerick. In the tradition of judicious marriages James’ sister Mary Catherine married Viscount Doneraile in 1752 and an alliance between the two families, whose seats were not far distant, was established and maintained throughout the nineteenth century, becoming an important point of reference for Redmond Barry.

By the time Redmond was born, on 7 June 1813, the Barrys of Ballyclough, although gentry, were no longer wealthy. They lived on the rents of their tenant farms, most of which had been set in the mid-eighteenth century and were not easily renegotiated or adjusted to changing economic climates. Sons served in the British Army, and the MacAdam Barry usually acted as High Sheriff of County Cork and local Justice of the Peace. Like all Anglo-Norman families the Barrys were only Protestantised in the Cromwellian period in the seventeenth century, the usual method being the early removal of sons from their families to be educated in England. The conversion in their case was a thorough one and by the early eighteenth century, according to family sources, the Barrys were playing a leading role in local Freemasonry. Their English allegiance was to remain central to their understanding of themselves. In the nineteenth century they were Conservative and high Tory in their politics, practising Anglicans rather than Protestants and implacably wedded to the property interests of the landed gentry.

At the beginning of the nineteenth century there were about five million people living in Ireland. Of these only about one-tenth lived in towns, the rest were on farms or in small villages and made their living in one way or another from agriculture. Ninety per cent of the arable land was owned by only five thousand men—landlords who let out their estates to tenants who farmed the land and paid a rent to their landlord. From 1793 until 1815 Britain was at war with France and as a result had turned to Ireland as a source of food. Prices of agriculture doubled over these years but rents also rose.

The nineteenth-century Irish countryside was deceptive. Admired by visitors for its beauty, in reality it was not peaceful but seethed with secret societies through which members sought to protect and advance their own interests. These societies had various names—the Cardens, Threshers, Whitefeet and especially the Ribbonmen—and were a type of rural trade union, using various degrees of persuasion to right what they saw as rural injustices. The government was strongly against them and when caught many members were hanged or transported to Australia.

Throughout the eighteenth century penal laws had repressed the Catholic majority while acting in favour of the Protestant landlords. They had created a society which, as Edmund Burke put it in 1792, was divided ‘into two distinct bodies . . . without common interest, sympathy or connection. One . . . was to possess all the franchises, all the property, all the education; the other was to be composed of drawers of water and cutters of turf for them’. As major landholders and prominent members of the Protestant Ascendancy the Barrys acted as local magistrates in Cork and their area at a time when justice was swift and summary, and magistrates ‘assumed the power of transporting the King’s subjects without trial, sentence or condemnation’. English law was practised by the ruling class in Ireland, a law which by the late eighteenth century had ossified into a powerful but disembodied entity seeming to be beyond class but in fact preserving the status quo. The post-Napoleonic years saw some recognition of the need for legal reform and in 1818 a parliamentary committee urged that some kinds of theft be punished by transportation rather than death and that forgery should cease to be a capital offence. By 1837 hanging was mainly restricted to cases of murder.

At the time that Redmond’s father, Henry Greene Barry, inherited Ballyclough, the economic boom that County Cork had enjoyed by virtue of its being a principal centre for the provisioning of the British military effort during the Napoleonic Wars (not to mention its importance as a centre for army and navy recruitment) was about to end. Frightening agricultural unemployment was a feature of Cork in the aftermath of the wars, although less acute in the Parish of Fermoy. The soaring prices and windfall profits of the Napoleonic Wars ended with the arrival of peace in 1815. A long, painful period of deflation followed, lasting until 1836 and corresponding with Redmond Barry’s youth. Corn prices declined drastically and farmers everywhere raised a cry for permanent reductions in rent. But Henry Greene Barry and his wife Phoebe were landowners and for them the rents from their tenant farmers were the means by which they hoped to raise and educate their thirteen children.

Now that the Act of Union had made the Church of Ireland the Established Church, the paying of tithes by the Catholic peasantry to a much resented clergy became the cause of great unrest in County Cork throughout the 1820s and 1830s. As a youth Redmond Barry would have been aware of a particularly violent hand-to-hand encounter near his relatives’ estates in Rathcormac in December 1834 between farmers and the military and police over an enforced tithe payment from a local widow. Not everyone, however, noticed the tensions between the peasantry and the law enforcers. Writing of Cork in 1835, John Barrow saw it as the second city of Ireland and rhapsodised about it and its picaresque inhabitants:

. . . Cork is a splendid city, and well deserving to be considered as the second in the kingdom, and its noble harbour the first . . . Indeed everything about Cork bears an appearance of wealth. The gentlemen, the ladies and the tradespeople dress much the same as in London; but among the common people the eternal great-coat hanging down to the heels and the women’s cloak with the hood over the head even in the hottest weather; under the cloak is generally a brown gown, a green petticoat, and blue stockings, if they sometimes wear a mob-cap.

Barrow was impressed by the busy port and the number of fine buildings and institutions in the city. He comments:

I was well repaid by a visit to the Institution for the Encouragement of Arts and Sciences: it boasts of a good collection of various specimens in the museum; and of a valuable library, to which the Duke of Buckingham has added the Irish works he privately printed. One of the apartments is filled with casts which were given by his late Majesty George IV . . . In the museum are some fine specimens of the horns of the fossil elk and moose-deer. It contains among other things, a great medley of articles, some of them odd enough: for instance, a pair of boots once belonging to O’Brien, the celebrated Irish giant. This specimen reminded me of the collection of boots in the museum at St Petersburg, from St Peter the Great down to the present Emperor Nicholas. In an open space in front of the building was a large living eagle from Kenmare. The institution was originally commenced by subscription, and assisted by annual parliamentary grants, which are now, I believe, discontinued.

The Cork Institution was an early Victorian example of the type of Library-Museum-Art Gallery complex which, in the 1850s and 1860s Redmond Barry was to strive so hard to establish in colonial Melbourne. In all probability it was here, in the early 1830s, that the young Redmond Barry, staying at his family’s town house, Killora Lodge, in Cork and cramming for his Greek and Latin entrance exams for Trinity College, saw for the first time the plaster embodiments of the classical past he came to revere. It is significant that Barry saw them in the context of a building which also included a library and a museum.

Redmond Barry’s father, Henry Greene Barry, was the third child and second son of James and Eliza Barry. He succeeded to the estates and title MacAdam Barry on the death of his unmarried brother Redmond, a first lieutenant of the South Cork Militia, in 1812. His sister Arabella did not marry and, inheriting a comfortable competence from her parents, set herself up in Malvern Wells, from where she took a keen interest in the lives of her nieces and nephews, having them visit her whenever possible. Prior to inheriting the estates, Henry Greene Barry had a distinguished career in the British Army. In 1804 as a lieutenant-colonel of the 18th Foot he had married Phoebe, eldest daughter of John Armstrong Drought of Lettybrook in the King’s County. He then saw service in the West Indies where his eldest son and heir James was born on the island of Barbados on 28 July 1805. Henry returned to Europe to fight in the Napoleonic Wars, becoming a major-general. He and Phoebe produced thirteen children, six boys and seven girls, all of whom survived infancy and childhood. Redmond was the third child and the third son.

Henry and Phoebe settled at the family seat, Ballyclough House, on the death of grandfather James and it was here that Henry retired after Waterloo to raise his large family and take up his responsibilities as a county farmer and High Sheriff of County Cork from 1821. Land-holdings in north-eastern Cork at this time varied between 100 and 1000 acres and the Barrys were apparently at the top end of this scale. The Griffiths Valuations, published in 1851 but conducted throughout the previous ten years, establish that Henry Barry’s heir and Redmond’s brother, Captain James Barry, owned and leased around 1000 acres at Ballyclogh, Ballylegan, Ballyamora, Ballynoe West, Boherash, Clontinty and Curraghagalla South, all in the Parish of Glanworth between Mitchelstown and Fermoy in eastern Co...