![]()

1

Economy and School

OVER THE LAST fifty years the economic dependence of the Australian population on secondary education has grown to such an extent that today, for most families, there is no refuge from the demands of academic success and no asylum for academic failure. At the end of World War II, every tenth child completed a school program leading to university. Today nearly eight out of ten do so. The trend to universal reliance on secondary education has unfolded in broken stages—the early post-war decades of rapid growth, the 1970s downturn after the first oil shock, recession and return to growth in 1982 and again in 1991, followed by stagnation for much of the 1990s. The economic impulse to greater use of school has involved both positive and negative moments—periods when strong economic growth and an upward shift in the structure of occupations has swept thousands of new students into school, and times when sharp cyclical downturn has turned school into an economic shelter, filled with learners anxious to leave. But over five decades, the flood tides of economic change have left the school system permanently altered. It is now almost completely integrated into national economic life, retaining groups who can get no foothold in the labour market, filling low-paid jobs with low achievers, shaping the tastes and expectations of more successful students, giving training and credentials. Secondary education is now exposed to the economic needs of the whole population.

Generalized economic dependence on the highest levels of schooling has meant that traditional ways of using secondary education for economic advantage have had to be abandoned. It has long ceased to be possible for aspiring doctors to have amongst the weakest school results of any group—as they did in the late 1930s—or for the best students to rely solely on their talent in the absence of wider competition. The strategic assumptions on which academic success used to be based no longer hold. The cost of wages forgone, the uncertainties of a job even after university, limited school places, and the cultural remoteness of the curriculum—these once cleared the approaches to university of most young people. Outstanding students could count on their own dedication and mediocre students on a system that did not demand dedication. Progressively, as economic dependence has increased, the average student has had to renounce mediocrity and the best student, the chance display of gifts.

Today success is based on the exercise of institutional power. Which students will succeed cannot be predicted from personal characteristics alone—from what families do independently of school—even though success does rise on average with each increase in socio-economic status. But which schools the best students represent is a matter of near certainty. And it is through schools that the insecurity of what merely happens 'on average' is removed. As the relationship between employment and qualifications tightens, schools grow in importance, both for the weakest students—whose economic vulnerability can only be offset by success at school—and also for the strongest, whose economic claims must be asserted through high standards of achievement.

On the eve of World War II, secondary education in its traditional sense—preparation for university—was poorly integrated in the economic life of the population as a whole and dependence on qualifications was quite limited. Only a small minority of children reached post-compulsory levels, usually to enter administrative and professional careers which at that time did not require a university degree. Postal officials, inspectors, bank and insurance clerks were recruited from the final years of secondary school, while primary teachers, nurses and pharmacists began a practical rather than theoretical training from this level. Going on to university was a remote affair. Writing of the rural community of Bairnsdale in Victoria's Gippsland region in 1939, Radford observed: 'University education as the climax of a successful career [at school] is scarcely ever considered, even for the most brilliant students'.

Even taking into account all forms of general and vocational education—secondary education in its modern sense—the extent of integration between school and work was weak, and most population groups did not rely on qualifications to maintain or advance their economic well-being. In country districts, boys returned to the farm once they were free to leave school or began manual jobs which needed little training. In towns, they worked on the railways, in workshops, local stores, or as apprentices. Their sisters had fewer jobs, and the largest single source of employment for them was domestic service. Girls in the cities could get factory work or serve in shops or offices, but many were domestic servants and large numbers returned home when released from school. They were often unable to find paid work.

In the inter-war years, many children left school even without a certificate of elementary schooling, and the development of various forms of post-primary schooling during these decades did not alter the pattern of separation between learning at school and gaining a job. Girls' domestic arts or home science schools and junior technical schools for boys had high drop-out rates. The vocational character of these establishments was deceptive. They were often used to accommodate children who were failing and who were 'retarded' for their age—as is revealed by comparative age patterns and by contemporary accounts of student placement policies. Despite the intentions of their founders, they did not evolve as vocational schools where children learnt industrial or business skills and entered the workforce already trained and productive. Ironically it was not the 'pre-vocational' establishments with their workshops, typing bays, kitchens and laundries which provided the smoothest passage to jobs, but the academic or 'professional' course whose curriculum was most theoretical or cultural and the most foreign to work.

The limited economic role of secondary education during this era can be illustrated from rates of attrition in the early post-war years. Of every 100 pupils entering public secondary schools in New South Wales in 1948, one-fifth had departed by the second year, over half by the third year, 87 per cent by the fourth year, and 90 per cent by the fifth year. While a proportion of pupils leaving public secondary schools transferred to private or Catholic schools, the overall pattern was one of very sharp reduction in the use of school once the statutory leaving age had been reached. Every second pupil endeavoured to gain the New South Wales Intermediate Certificate—representing an extra year above the norm—but only about 13 per cent attempted another year and only 10 per cent the Leaving Certificate. In Victoria, the Intermediate Certificate was delivered in the fourth year of secondary school. Again somewhat less than half of all children in public post-primary schools reached this year, with 18 per cent attempting their Leaving Certificate after another year and only 7 per cent entering the sixth or Matriculation year.

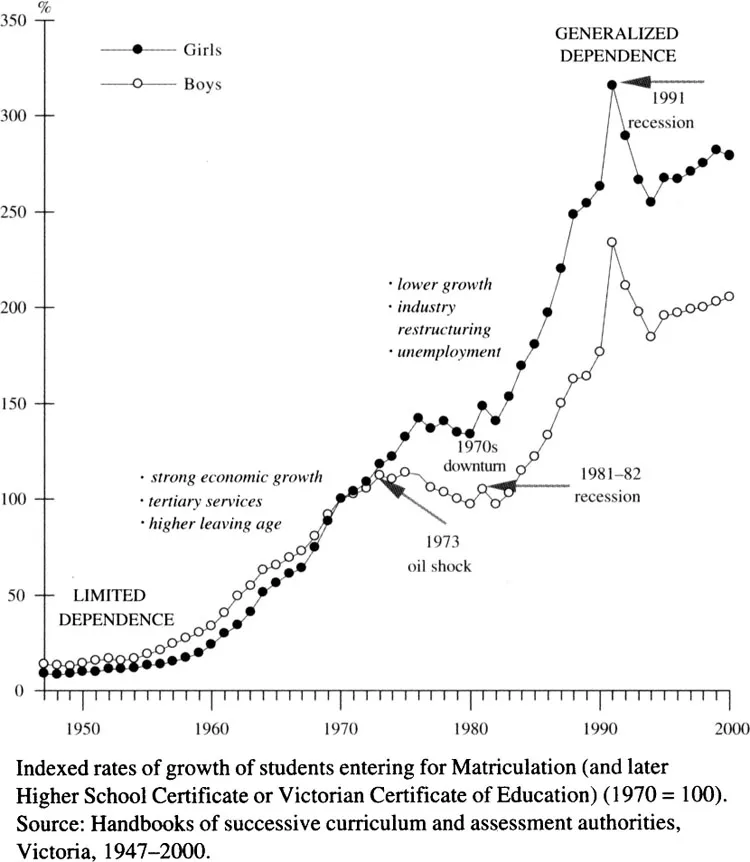

Matters changed rapidly in the boom years of the late 1950s and 1960s. Economic expansion required skilled workers, technicians, office and sales workers, and health, education and other professionals. Rising incomes supported longer schooling, and the channelling of aspirations into white-collar and professional careers was underwritten by immigrant labour in low-paid construction and factory jobs. The use of secondary school accelerated. When manufacturing industry began to decline in the mid-1960s, opportunities became increasingly concentrated in the services sector of the economy. Employment in finance, insurance, real estate and business services, in public administration, in schools and hospitals, and in large wholesale and retail concerns grew rapidly between 1947 and 1971. Industry change in this direction increased the economic significance of school qualifications, while alternative roads to employment involving early school leaving and apprenticeship or informal on-the-job training began to decline. The full impact of these structural changes on demand for higher levels of schooling was delayed by slower employment growth after 1974 and by economic conditions which dampened confidence in further schooling and university. But the prospects of a return to past strategies for employment in which only limited use of school was made were closed by the sharp recession of 1982. This ended a phase in which school completion rates had stabilized or fallen and pressure for university places had markedly eased. During the 1980s, the proportion of young people reaching the final year of secondary school doubled, access to apprenticeships for early school leavers was permanently reduced, and rapidly mounting numbers entered university. Figure 1.1 shows the main phases of growth in demand for completed secondary schooling in Victoria over the period 1947 to 2000, set against the background of the changing economic environment.

Qualifications and jobs

The shift to generalized economic dependence on school can be detected in rising qualification levels. In the mid-1950s, many of the estimated 15 000 engineers at work in Australia were not university-trained. They had graduated from technical colleges with professional or technical qualifications, and not a few had only a craftsman's certificate, acquiring much of their training on the job. By the early 1990s, over 80 per cent of practising engineers had at least a two-year technical diploma, 62 per cent had at least a bachelor's degree, and 11 per cent had a postgraduate diploma or higher degree. A cross-section of building professionals and engineers at the 1991 census shows that almost one-third of men aged 55–64 years had only a basic or skilled vocational certificate, while over 80 per cent of men under twenty-five had a bachelor's degree. Similar trends can be observed amongst technicians in building and engineering. In 1991 only about one in five of the group aged 55–64 had a two-year Associate Diploma or other award, while three-quarters had only a craftsman's certificate or a basic vocational qualification. By contrast, amongst younger technicians in building and engineering industries, over 40 per cent had at least a two-year award and some held degrees.

During the decades of growth, professional organizations such as the Institute of Engineers sought to raise entry standards in line with the perceived training needs of their members and greater public recognition. The Australian Society of Accountants argued to the Martin Committee in 1964 that courses in accountancy taught in institutes of technology should 'incorporate studies of a more liberal nature . . . to ensure that [students! reach a standard of general education equivalent to university entrance'. Institute of technology courses did not reflect emerging work demands on accountants, who needed to be more management-oriented and to have a wider understanding of the economy. The quality of students should be raised through a broadening of programs and by discouraging narrow vocational expectations. The Institute of Chartered Accountants announced its intention to restrict its ranks to university graduates as it set its sights on examining standards for postgraduate students.

Health sciences show a similar trend towards an upward revision of entry standards and demands for higher professional recognition based on this mechanism. By the early 1960s, pharmacists were mainly educated in universities, though in a few states the older pattern of lower entry standards and training through a professional society remained. The Australian Optometrical Association had not yet succeeded in having courses for its members raised to degree status. Nursing—the most widely established health service—had admission requirements regarded as too low by nursing teachers. Higher educational standards were needed to manage the increasing complexity of medical care. In Victoria, 28 per cent of students entering nursing schools in 1961 had completed only three years of secondary school and only 48 per cent had their Intermediate Certificate. The Martin Committee opposed the upgrading of entry standards leading to degree courses for nurses, optometrists, physiotherapists, and speech therapists. But within about two decades, training for all these and other health professionals would be firmly established within universities, and often in high-demand courses with stringent selection requirements.

Less visible than the transformation of the status of health professionals has been the progressive upgrading of entry levels in skilled manual trades. Up to the early 1980s, apprenticeship opportunities grew strongly in Australia, in part because government subsidies tended to counteract the underlying deterioration in the full-time labour market for teenagers. Recession in 1982–83 cut apprenticeship intakes by one-third and triggered a sharp upswing in school retention rates. The long-term effect of this recession was to permanently reduce apprenticeship opportunities for the youngest school leavers and to advantage those with at least five years' experience of secondary school. The recession of 1990–91 had a still more drastic impact on apprenticeship commencements and again raised the bar in favour of the most highly schooled individuals. This trend is reflected in the declining share of new indentures held by younger teenagers over the period. In Victoria, for example, 15–16-year-olds took up 30 per cent of all new positions in 1990, but within one year this had fallen to 19 per cent and has remained at this level ever since.

Economic marginalization through school

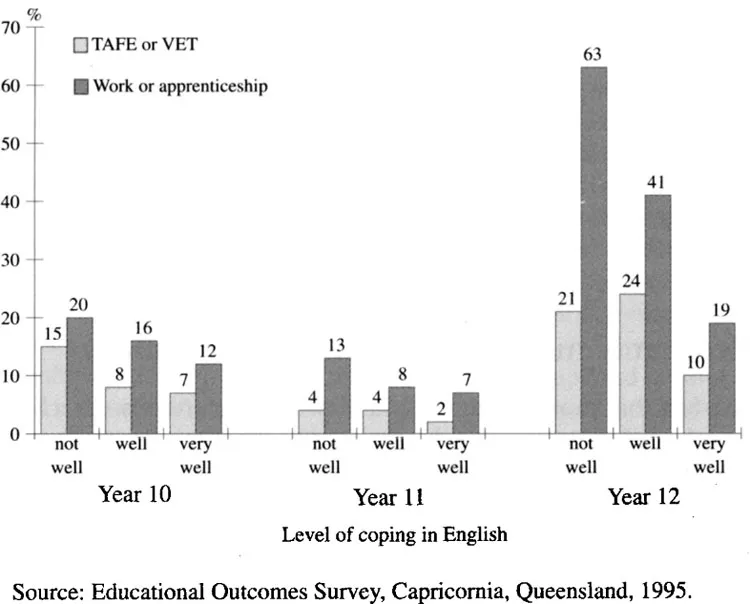

The fact that more young people than ever before rely on school for jobs or further training does not mean that school is an equally effective path for all groups. Global economic dependence on school does not imply successful use of school and is compatible with economic marginalization through school. Decisions to leave school early are influenced more by quality of learning experience than perceptions of job availability. It is students with the lowest marks who are most likely to quit school. Data from Capricornia in Queensland show a pattern which is found across Australia, in which intentions to leave school and look for work rise as student achievement falls. Only 12 per cent of boys in Year 10 who say they are doing 'very well' in English intend to drop out, compared to 16 per cent who are coping 'well' and 20 per cent who are coping 'poorly' or 'not well'. Amongst those students who do continue to Year 12, it is the low achievers who most often reject further training at the end of school—63 per cent compared to 19 per cent of the group coping best (Figure 1.2).

Tracking of students confirms that those who actually do leave school early often have the poorest results and the lowest academic self-esteem. As learning weakens, young people adjust their perceptions of what they hope to gain by staying on at school. Low achievers more frequently want to start work and they attach more importance to job skills than good marks. The fading prospect of 'careers' based on university or TAFE is compensated by an optimistic view about jobs being available for those who 'look hard ...