![]()

![]()

| 1 | PAPERWORK KINGS, ENGINES OF STATE |

| THE BIRTH OF THE OFFICE |

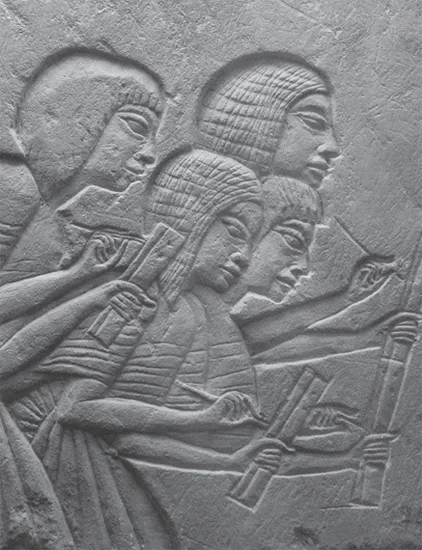

Egyptian scribes: the original stylus-pushers

‘Come at once and bring your electric torch,’ read the note. ‘Good luck at last.’ It was late one evening in March 1920 when his fellow Egyptologists found this note from their colleague Harry Burton, but so dogged by misfortune, bad weather and ransacked chambers had their expedition been that they hastened to the tomb near Luxor, so far fruitlessly excavated. Near the entrance stood Burton, a knot of Arabs, and a yawning black crack between the wall of the corridor and the rock floor. When one of their number shone a beam of light into this ‘little world of four thousand years ago’, he was dazzled by ‘a myriad of brightly painted little men going this way and that’.

From the tomb of Meketre: upstairs in the granary, model scribes get to work 4000 years ago

Meketre had been a senior official in the court of Mentuhotep II. A wall relief furnished an impressive business card: ‘The Count, the Treasurer of the King of Lower Egypt, the Hereditary Prince at the Gateway of Geb, the Great Steward, the Sole Companion and the Chancellor’. He had been sent on his way to the afterlife accompanied not by pharaonic treasure, such as Burton would famously disinter two years later from the tomb of Tutankhamun, but with an extraordinary array of funerary models of everyday Theban life circa 2000 BC, representing Meketre's residence, cattleyard, carpenter's shop, butcher shop, weaving shop, granary, brewery, bakery, plus no fewer than nine boats and two canoes. And on the upper level of the granary, now behind glass at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, ten of those 20-centimetre figures, carved in coniferous wood, are performing something unmistakeable: office work.

There is an overseer, a doorkeeper and three figures bearing baskets of grain, but busiest of all are four scribes, squatting on the floor. Two are poised to write on broad wooden tablets, whitened in imitation of the plaster with which such boards were faced; pen cases lie nearby. They share a large white water jar for moistening the ink, smudges of which are represented on the outside. Two sit opposite, left knees raised, papyrus scrolls ready, writing palettes before them on square document boxes with cleated lids. Thus are represented two timeless clerical functions: copying and record-keeping. Egyptian practice, in fact, was to triplicate important deeds, and to close letters with exhortations to preservation such as ‘I write this to you that it may serve as a witness between us, and you must keep this letter that, in the future, it may serve as a witness’.

The layout of the granary model, the rest of which is allocated to grain handling and storage, establishes a perennial division of labour: downstairs manual, upstairs clerical. More subtly, the model conveys a truth of the history of the office: that it was an activity long before it was a place. The office did not come into being like the spinning jenny or the factory system. It was first an area—in a warehouse, in a store, in a home—cleared for keeping a ledger or writing a letter. Office functions are as old as commerce; the customised physical location is a far more recent development. Meketre's little wooden scribes have brought their work with them, creating what would best be described as a ‘counting house’. In the absence of their papyrus and palettes, the area would revert simply to a space.

Still, the model bears out an early separateness of, and esteem for, clerical skill. In contrast to the sturdy, sun-darkened labourers, Meketre's scribes are slim, fair and shaven-headed. They repose at his right hand in another model, of the cattleyard, where livestock are being counted for the rendering of tax. Again they tote papyrus rolls, with writing palettes and document boxes handy; a colleague, flanked by brawny cattlemen, keeps count on his fingers. By his proximity, Meketre the steward and treasurer confers rank on his educated aides, and it is without condescension: to the Ptolemaic bureaucracy supervising the coffers, cargoes and censuses of Egypt's complex command economy, scribes were recognised as indispensable. In The Satire of the Trades, a didactic work from 1400 BC, a scribe named Dua-Kheti exhorted his son Pepi to consider the hardships of all occupations bar his own: ‘I'll make you love scribedom more than your mother/I'll make its beauties stand before you/It's the greatest of all callings/There's none like it in the land.’

Wherever there was commerce and trade in the ancient world, there were antecedents of the office, from the slate shelves on which were stored the clay tablet letters of Babylon's Hammorabi to the catalogue system devised by Aristotle for temple papyrus rolls. The Romans, for example, were brisk and compendious note-takers, perfecting a form of shorthand based on the first letters of each word, essayed for maximum speed by styluses on wax tablets. Mind you, ancient filing had a peculiar characteristic: a tendency not to distinguish between documents new and old, for regular use and not. Archaeologists tend to find archive rooms difficult to identify because, German archival educator Ernst Posner has noted, ‘most of the time we cannot tell whether we are dealing with an archival aggregate or with … the equivalent of a modern waste-paper basket.’ This applies even to the biggest building to survive from Republican Rome, the Tabularium, erected in 78 BC on the front slope of the Capitoline Hill. This giant repository for official records attests the Roman reverence for documentation, but no deep interest in its retrieval. Scrolls and codices went in all right, but apparently seldom came out—rather like a modern filing cabinet.

The growth of Rome and its empire required bureaucratic solutions of increasing complexity. The first management case study, as it were, can be credited to Sextus Frontinus, who of his activities as Rome's curator aquarium (water commissioner) in the first century AD bequeathed a detailed textbook, De aquis urbis Romae (About the Water of the City of Rome). To maintain and preserve the integrity of the aqueducts, pipeworks and channels of his water works, Frontinus had charge of 700 architects, engineers, clerks, apparitores (public servants), lictors (bodyguards) and praecones (criers). Of their daily schedules, Frontinus' text teems with detail. But of his headquarters, comparatively little is known, apart from it being set in a colonnade, Porticus Minucia, from which doles were also distributed—again, the functions precede the location. And for all but the very few, ancient work was centred on the home, the store or the warehouse, where, as in Meketre's granary, an area could be set aside for record-keeping as required. The concept of fixed, dedicated, cellular workspace had a later inspiration.

Savonarola's desk: a place for everything

MONKS AND MERCHANTS

At the end of the novices corridor in Florence's San Marco convent, today a museum, the quarters of Savonarola are as bare as the visitor would expect. The cell and oratory contain a cloak, a fragment of Savonarola's habit, and two hair shirts. What looks worldly, even rich, for a figure so identified with personal austerity, is the desk in his study, which the modern expression ‘workstation’ would fit perfectly: a self-contained unit consisting of bench, sidetable, slanted bookrest, storage space and raised platform. The seat is hard, of course. The message is clear—this is a place for work.

St Gregory of Nazianzus and desk: everything in its place

Monasteries were where work was first rationalised. The inaugural Benedictine monastery, established at Monte Cassino in 529, hewed to strict written guidelines, partitioning the day into compartments of prayer, reading, translating and artwork, commencing at 1 a.m. in summer, 2 a.m. in winter. Dividing time in such a way divided space: variegated activities required different areas for collective and solitary endeavour, from scriptoria for the mass copying of manuscripts, to studies and cells for study and contemplation. The settings crafted specifically for sedentary concentration sometimes look uncannily predictive. In one eleventh-century Byzantine codex, St Gregory of Nazianzus has his feet on a footrest, his work stored in a doored cabinet and his eye fixed on a bookmount that might almost be a flatscreen monitor. In both Botticelli's St Augustine in His Cell (c. 1490) and Antonello da Messina's St Jerome in His Study (c. 1460), the venerable divines express work as a process: St Augustine's feet are surrounded by crumpled paper and discarded quills; St Jerome has a scraper at the ready in case of spilled ink. The St Jeromes of Jan van Eyck (c. 1435) and Domenico Ghirlandaio (c. 1480), propped on their elbows over bulky texts, even look a little bored.

With the spread of Christendom, religious orders developed considerable organisational skills. To the Cistercians, for example, we owe the idea of the large-scale conference. From the twelfth century, their ‘general chapter’ every Holy Cross Day brought representatives of its hundreds of monasteries across Europe to the Citeaux Abbey, the only such gathering in its time. The Jesuits would later be renowned for the opposite, a policy of extreme decentralisation, St Ignatius Loyola binding his far-flung emissaries by a constant stream of correspondence from four tiny, low-ceiling rooms in a house adjoining a church in Rome: Santa Maria della Strada. Loyola and his chief secretary kept three copyists occupied all day every day, composing multiple drafts of letters and filing copies in two chests. From the fourteenth century, too, monastic time management gained general application, as public town clocks imposed on the day a discipline long known in religious orders. When Max Weber observed that work made ‘every man a monk’, the historical precedents were solid.

Not all monks, of course, maintained Savonarolan self-denial. In Chaucer's ‘The Shipman's Tale’, the monk is a charming, lusty rogue who enlists the comely wife of a hapless merchant in defrauding him. There is something decidedly modern about the scene in which the wife remonstrates with her husband, who is struggling to make sense of his accounts: ‘How long tyme wol ye rekene and caste/Youre sommes and youre bokes and youre thynges?/The devel have oart on alle swiche reckenynges!’ Many a weary businessman has echoed his plaintive reply that he is busy, that commerce is hard and that merchants ‘stonde in drede of hap and fortune’. Such overlap of home and work was natural: until the eighteenth century, rooms in European houses had no fixed functions, and family members little privacy. Strangers circulated freely; tables, chairs and beds were shifted according to the occupants' moods, needs and appetites. How did people work under these circumstances? A remarkable historical find fifty years before Harry Burton's has given clues.

Born in about 1335, Francesco di Marco Datini carried on a variety of businesses, mainly the importing and dyeing of textiles, in an unprepossessing residence on the corner of Via del Porcellatico and Via Mazzei in Prato, near Florence. The ground floor featured a small cellar, a guest room and what was called an ‘office’ but was actually a storeroom—his actual operational base was a warehouse at the foot of his garden. There, among bolts of cloth, ingots of iron, supplies of sandalwood, soap, resin, alum, hides, skins, woad and madder, were four writing desks, one ‘with a cover’, another ‘with a little chest’ for secure storage. There were two baskets for letters, a cupboard and a bowl for cash, all painted in grass-green; a mirror ‘new and fine and good and clear’ provided reflected illumination, an unspecified sacred picture on the wall direct inspiration. This we know because 500 ledgers and account books, 300 deeds of partnership, and no fewer than 120 000 letters to and from more than 200 locations encompassing all aspects of Datini's activities were found intact in the annex of the building in 1870.

For all its complexities, Datini's was a Christian enterprise. The first ledger was dedicated ‘in the name of God and of the Virgin Mary and of all the saints of Paradise, that they may give us grace to do right both for body and soul’; dedications on subsequent books followed such religious formulae as ‘In the name of the Holy Trinity and of all the Saints and Angels or Paradise’ and ‘In the name of God and of profit’. Letters, too, were fervent in their avowals. ‘You say you have written to Venice to remit us 1000 ducats with which in the name of God and of profit, you wish us to buy Cotswold wool,’ reads a 1403 receipt to a London correspondent. ‘With God always before us, we will carry out your bidding, which we have well understood.’ Datini's staff was a small band of literate fattori-scrivani (letter-writers), numerate contabili (bookkeepers) and chiavai (cashiers), plus unlettered garzoni (shop boys, who undertook menial tasks and were messengers), all of whom he expected to be ‘humble, loyal, solicitous, steady, honest and orderly’. Datini nonetheless carried much of the business in his head. ‘To confide in a man is to turn yourself into his slave,’ he believed. ‘When you have lived as long as I and have traded with many folk, you will know that man is a dangerous thing, and that danger lies in dealing with him.’ The relationship that mattered to him chiefly was with God, and he wondered increasingly how his heavenly welcome would be affected by his laying up of treasure on earth—thus the posthumous bequeathing of his home and fortune to the poor of Prato, and the fortuitous survival of his records.

One development that would have eased Datini's quotidian apprehensions was double-entry bookkeeping, a Roman notion revived in Florence in the thirteenth century, and which Datini adopted in about 1380. Before double-entry, bookkeeping had been more like keeping a diary, noting the payment of a supplier here, the arrival of a consignment there. With double-entry, which recorded transactions twice, in separate accounts, as a debit and a credit, it became theoretically possible to ascertain the financial well-being of any enterprise at any given time. On his death, Datini knew that he was worth, and the poor of Prato would be benefiting by, 70 000 ducats. Goethe called double-entry bookkeeping ‘one of the finest discoveries of the human intellect’; the economist Joseph Schumpter would deem it capitalism's ‘towering monument’. And, in the Summa de arithmetica, geometrica, proportioni et proportionalita (1494), in which he codified the practice after about 200 years of usage, Luca Pacioli treated it as a commercial imperative: ‘If you cannot be a good accountant you will grope your way forward like a blind man and may meet great losses.’ He recommended, too, the use of Hindu-Arabic numerals for every entry save that of the year, so although the book was published in ‘MCDXCIV’, everything else is comprehensible to the modern reader.

The sweep of the revolution can be sensed from Bruegel the Elder's Temperance (1560), the lower left of which is devoted to a merchant counting his money, a clerk calculating in Hindu-Arabic numerals, and a peasant jotting calculations on the back of an old bellows. Temperance herself overlooks the scene, holding spectacles, symbolic of wisdom, and reins, symbolic of restraint, and perched on her head is a clock, evoking order and procedure. A combination of monks and merchants had brought commerce to the brink of modernity.

BANKERS AND BUREAUCRATS

Not far from Datini's warehouse/counting house, an enterprise was fructifying that would become synonymous with commercial power. Ambitious gente nuova (new men) from the Tuscan countryside were enriching Florence by their mastery of foreign exchange and trade finance: the Bardi, the Peruzzi, the Acciaiuoli and, above all, the Medici, whose founder, Giovanni, wrung from his friendship with Pope John XXIII every possible benefit. For in spite of usurers sharing the third ditch of the seventh circle of Dante's hell with sodomites, it was Catholicism that provided early banks with much of their business: tribute-bearing pilgrims bound for Rome and wishin...