![]()

1

A British Outpost in the Pacific

David Dutton

ASIA WAS RARELY INVOKED during the decade-long process that led to the federation of the six Australian colonies in a new Commonwealth of Australia. The driving motivations of Federation were matters associated with governance and commerce, rather than any feature of Australia’s geographical or geopolitical situation. Yet the founders of the Commonwealth and the politicians and bureaucrats who established its structures and policies over the first decades of the twentieth century were conscious of Australia’s proximity to Asia. They often observed that Europe’s ‘Far East’ was Australia’s immediate north, and that Australia’s future was bound up in the affairs of Asia and the Pacific. George Pearce, a Senator from 1901 to 1937 and a government minister for many years, put it this way in 1922:

Awareness of Asia’s nearness and significance manifested itself most clearly in three areas during the Commonwealth’s first twenty years: migration and population policy, where the White Australia policy attempted to set the conditions for developing a racially united nation; strategic thinking and naval and military policy, where perceptions of Asian threats to Australian security were pessimistic and sometimes paranoid; and trade, where the ideological split between free trade and protection confronted fantastic notions of Asia’s potential to consume. Political and public deliberations over these issues reveal much complex and contradictory thought on Asia and its relationship to Australia, little of which was based on close knowledge or study of Asia. Australia’s perceptions of Asian countries and people over the first decades of the twentieth century were filtered through the concepts of European imperialism and race, and its contacts were mediated through the conduits of the European empires which ruled or controlled almost all of Asia. Japan was the exception: the only modern sovereign state in Asia in 1901. Japan’s rapid advance to the status of a major naval and economic power in the space of half a century was observed with both wonder and trepidation in Australia, and it was with Japan that the Australian government grappled at every turn. This chapter proceeds by explaining the nature of the Australian state inaugurated in 1901, before moving to the development of policy on migration, security and trade, and finally turning to the Great War, and in its aftermath the reconstruction of the world order as it altered Australia’s relationship with Asia.

A Self-governing British Dominion

With due regard to the calendar, the Commonwealth of Australia was established by act of the British Parliament on the first day of the twentieth century, 1 January 1901. An official ceremony with assorted dignitaries was held in Sydney’s Centennial Park, while parades and celebrations were held around the newly unified country. Australia’s small Asian population was prominent in the celebrations, particularly in Melbourne where the local Chinese community erected a Federation arch. Some Australians living in Asia held their own festivities; for instance, the New South Wales and Victorian contingents in China, serving under British command after the Boxer Rebellion, welcomed Federation at Peking and Tientsin.2

Plans for arranging the self-governing Australian colonies in a federal structure had been mooted regularly during the second half of the nineteenth century. However, it was not until the 1880s that these suggestions met with serious deliberation. At the instigation of Sir Henry Parkes, the New South Wales Premier who proved central to federal matters until his death in 1896, a Federal Council of Australasia was founded by intercolonial agreement, and proclaimed by imperial statute in 1885. Predicated on the unreadiness of the colonies to proceed to a fuller union, the Federal Council provided a biennial forum for considering matters affecting the colonies generally. The Council continued to meet until the adoption of the federal agreement in 1900 rendered it redundant, but it proved ineffective. New South Wales refused to join after Parkes became hostile to the Council, New Zealand also declined, Fiji attended just a single meeting, and South Australia withdrew in 1891, leaving just four members. It had no authority over trade and customs, it lacked executive powers, and the implementation of its decisions relied on each of its members abiding by those decisions.3

Parkes’s dissatisfaction with the Council, enthusiasm for a better federal agreement, and an eye for his place in history moved him to revive discussions over Federation. At Tenterfield in northern New South Wales in 1889, and in an interview given a few days earlier to the Brisbane Courier, Parkes took a report on the colonial military forces as a pretext for expounding the necessity of Federation for defence.4 He proposed a meeting of colonial representatives to discuss a new federal scheme. Despite scepticism at Parkes’s motives and suspicions that his proposals were inspired to a large degree by vanity, the rejuvenated interest of New South Wales was welcomed by Victoria and the other colonies. An Australasian Federation Conference was convened in Melbourne the following year, followed by a National Australasian Convention in Sydney in 1891. Representatives of all the Australian colonies and New Zealand attended the conventions. A constitution was drafted and circulated to colonial governments. There the process stalled on the reluctance of some parliaments to cede power to a central government and discontent with main elements of the federal bargain.

A Chinese Arch erected for the celebrations of Federation, Melbourne, 1901.

Federationists sought to whip up a popular movement in favour of Federation over the next few years, establishing an Australasian Federation League and convening ‘people’s conferences’, participation in which was carefully controlled. Leaders and supporters of this movement were drawn almost exclusively from the middle, commercial and professional classes. Their ardour for Federation was met by active hostility on the part of some radicals and conservatives and widespread public indifference.3 Nonetheless, a movement for Federation took shape, designed to popularise the process of achieving Federation and circumvent opposition from the upper houses of colonial parliaments. By grounding the federal process in popular sentiment the Federationists hoped to strengthen their position and broaden its cause beyond prosaic concerns with matters of intercolonial administration.

A group of Australian naval brigade officers and men serving in China during the Boxer Rebellion, 1900–1.

By these tactics the movement towards Federation was revived. A new National Australasian Convention was organised in 1897, this time comprising elected representatives (except in the case of Western Australia which appointed its delegates). New Zealand dropped out of the process. The delegates included many of those present six years earlier in Sydney, and the Convention picked up the draft constitution where it had been left off. The Convention met in three sessions between March 1897 and March 1898 in, successively. Adelaide, Sydney and Melbourne. During four months of debate the draft constitution was reconsidered, and compromises reached on a range of controversial matters. Once approved by the Convention, the draft constitution bill was submitted to referenda in Victoria, South Australia, Tasmania and New South Wales in June 1898. Victoria recorded 82 per cent in favour, but in New South Wales the small majority voting ‘yes’ fell short of the required number of affirmative votes (80 000). Indifference to the proposition was widespread: less than half of registered voters exercised their franchise in Victoria, and only 35 per cent did so in South Australia. In New South Wales 46 per cent voted, a somewhat higher turnout reflecting the controversial nature of the proposal in that colony.6

Further negotiations between the premiers made the bill more palatable to New South Wales, and at a second referendum in 1899, which this time included Queensland, all the colonies voted for Federation. The majority in Victoria was even more massive than before (94 per cent), while New South Wales and Queensland opted for Federation only on the back of the rural vote. The turnout was slightly higher than in the previous year, but still only about 60 per cent of registered electors voted. Western Australia held its own poll in 1900, and also agreed to join the Commonwealth. Far from embracing Federation, a substantial number of people voted ‘no’ in both 1898 and 1899, and around 40 per cent of the electorate was not sufficiently inspired to visit the polls at all. These figures refer only to registered voters, and registration was not then compulsory. The electorate was hardly democratic: women could vote only in South Australia and Western Australia; there were racial restrictions on voting in several colonies; residence qualifications existed in every colony; in Tasmania a property qualification applied; and plural voting for people with property existed everywhere except New South Wales and South Australia.7 While some sections of the population cultivated and acted out of a sense of Australian nationalism, and the latter stages of the Federation process included democratic elements to engage the population, Federation was not a nationalist or popular accomplishment.8 Nonetheless, with the imprimatur of the colonies’ voters, the draft constitution was presented to the British government. Several amendments were agreed in the negotiation between the Secretary of State for the Colonies and Australian representatives, the most significant reinstating the Privy Council as the highest appellate court largely in order (as was stressed at the time) to protect British capital. The British Parliament then passed the Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act in July 1900.

The success of the federal project rested on a consensus among the middle, commercial and professional classes, and their politicians and lawyers, that there was a pressing need to extend state power over borders. The single most important motive for Federation was the desire to remove intercolonial barriers to the movement of goods and people and replace them with a legal structure sufficient for the conduct of commerce and finance across the continent. Intercolonial trade had been hindered not only by tariff barriers but by the starkly different trading policies of New South Wales and Victoria, respectively free trade and protection. Unable to resolve this dispute, the founders left it to the new Commonwealth Parliament, which would continue to wrangle over it for several years until protectionism won out.

The founders wished also to impose stronger and uniform controls on the movement of capital, goods and people in and out of Australia. In this respect at least, Federation was motivated by the vulnerability of colonial governments to external forces. As for vulnerability in a military sense, its significance as a motive for Federation is often overstated. While defence provided the pretext for Parkes’s call for a federal government with executive powers, it was not prominent during the long negotiations over the constitution and the nature of the Federation. Indeed, Federation was not a prerequisite for an adequate defence policy. However, it did produce a structure of executive government capable of implementing a defence policy, and this is discussed later in the chapter.

The Constitution invested in the Commonwealth of Australia powers to bring about trade and customs union, to establish controls over direct investment and capital inflow, to regulate banking and finance, to intervene in industrial disputes extending over state borders, and to control the movement of labour. In these ways it provided the conditions for commercial stability inside Australia. What the Constitution did not do was establish an autonomous, sovereign nation-state in the contemporary European or American mould. In fact, creating an independent state was never the aim. The Commonwealth remained within the structure of the British Empire, and Federation was initially regarded by the Colonial Office in London as little more than an internal rearrangement of colonial self-government. Sovereignty continued to reside in the Crown, and the British government retained ultimate jurisdiction over Australian law. While no Commonwealth bill was actually refused assent by the British government, the possibility hung over parliamentary deliberation, and refusal was considered likely if the Commonwealth, for example, passed legislation for the direct exclusion of Asians from Australia.9 The British Parliament also kept the right to legislate for the Empire as a whole, and any Australian statute inconsistent with such legislation was invalid. In practice, this occurred only rarely. But the point remains that the Commonwealth of Australia was hardly more independent in 1901 than its constituent colonies had been before Federation.10

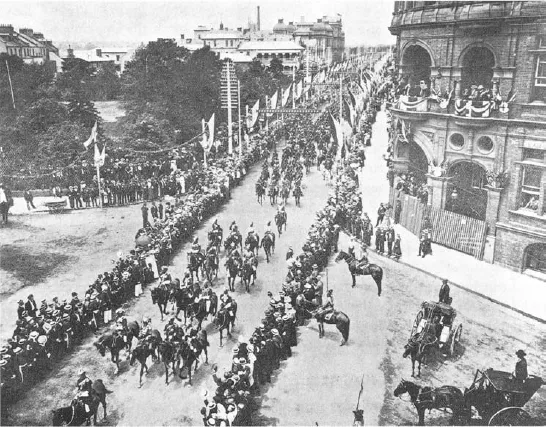

The Indian contingent to the Federation celebrations parading past the Australian Club in Macquarie Street, Sydney, 1901.

The term ‘dominion’ was coined to describe the self-governing units of the British Empire: Australia, Canada, Newfoundland, New Zealand, South Africa from 1910, and later the Irish Free State. ‘Dominion status’ entailed the British government consulting the dominions at periodic colonial conferences (called imperial conferences from 1911), and informing them of certain aspects of foreign affairs and trade relations, but its meaning was never clearly stipulated. At the Imperial War Conference in 1917 it was resolved that the relations of the various components of the Empire ‘should be based on a full recognition of the dominions as autonomous nations of an Imperial Commonwealth’,11 but this fell short of the status of autonomous states. At the Paris peace negotiations following the Great War the dominions were represented on the same scale as minor allied powers but without separate voting rights. Australia signed the peace treaties and joined the League of Nations, since membership of the League accommodated self-governing dominions and colonies, as well as sovereign states. The Statute of the Permanent Court of International Justice enacted in 1920 went further by granting the dominions the status of independent states.12 Nonetheless, in international affairs the dominions remained subordinate to Britain.

The bounds of Australian power at Federation were nowhere more apparent than in the domain of external affairs. The Constitution endowed the Parliament with powers over ‘External affairs’ and ‘the relations of the Commonwealth with the islands of...