eBook - ePub

Darwin's Screens

Evolutionary Aesthetics, Time and Sexual Display in the Cinema

- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Darwin's Screens addresses a major gap in film scholarship—the key influence of Charles Darwin's theories on the history of the cinema. Much has been written on the effect of other great thinkers such as Freud and Marx but very little on the important role played by Darwinian ideas on the evolution of the newest art form of the twentieth century. Creed argues that Darwinian ideas influenced the evolution of early film genres such as horror, the detective film, science fiction, film noir and the musical. Her study draws on Darwin's theories of sexual selection, deep time and transformation, and on emotions, death, and the meaning of human and animal in order to rethink some of the canonical arguments of film and cinema studies.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Darwin's Screens by Barbara Creed in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film & Video. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Darwin, early cinema and the origin of uncanny narrative forms

It [the uncanny] is a crisis of the natural, touching upon everything that one might have thought was ‘part of nature’: one’s own nature, human nature, the nature of reality and the world.

Nicholas Royle, The Uncanny

A sustained exploration of Darwinian ideas first appeared in early cinema through the cinematic adaptation of popular Gothic novels. The 1880s witnessed a revival in Gothic literature that extended into the twentieth century. Classic themes of ghosts, haunted houses, madness and death were displaced by a new interest in fin de siècle themes that were influenced by Darwin’s theories and the ensuing struggle between religion and science. These included themes of decadence and degeneration, the collapse of traditional social structures, the sexually aggressive woman, the horror of crossing boundaries, the dangerous allure of the foreign, and the fragile line between human and animal species. In one way or another, these motifs drew on the power of the uncanny to unsettle and disturb the reader. Novels that explored the Darwinian uncanny included Bram Stoker’s Dracula, Sheridan Le Fanu’s Carmilla, Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, HG Wells’s The Island of Dr Moreau and The Time Machine, and Edgar Rice Burroughs’s Tarzan of the Apes. In a number of Imperial Gothic novels, such as Rider Haggard’s She, the crossing of geographical boundaries is represented as a source of horror associated with threats of primitive desire and devolution.1 These texts were all adapted into films during the first decades of the silent period and the first years of sound in the 1930s; these films drew heavily on the uncanny, and its focus on the double, to create atmosphere and to disturb the viewer.2 Many have been made and remade over the years. Although the popular Gothic novels of fin de siècle culture were generally not seen as warranting critical attention at the time, many did explore serious issues, particularly those arising from the Darwinian revolution in ideas.3

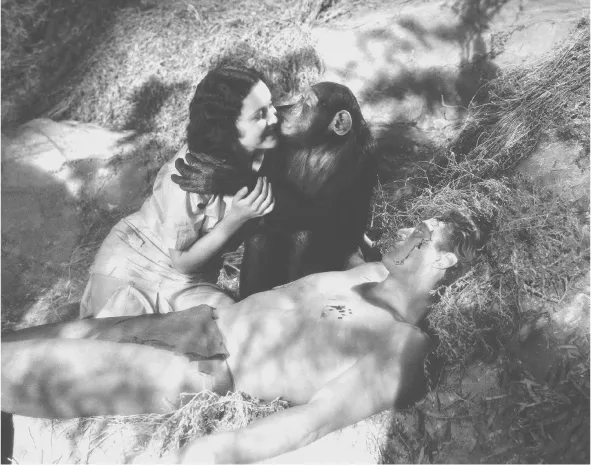

Despite the fact that Darwin did not say that man was descended from the apes, but from a common ancestor, many thinkers of the period, such as Huxley, argued that it was clear that public opinion would dwell on the possibility that man was descended from the apes. The Gothic novelists, and the films adapted from their texts, examined this problem from various perspectives. What was the nature of man? Was he composed of a double being—one human and civilised and the other animal and primitive—as Stevenson proposed in Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde? Bram Stoker pushed the boundaries of what constituted the ‘human’ in his Gothic horror novel Dracula. Is man able to exert a primitive, hypnotic sexual power over woman? What kind of monster is able to metamorphose and assume the form of other creatures? HG Wells, who studied under Huxley, the famous Darwinian scholar, was particularly interested in issues of devolution and entropy or human degeneration. How strong is the animal in man and woman, Wells asks in The Island of Dr Moreau? If man can evolve, is he capable of devolution? Wells explored this question in his classic science fiction novel The Time Machine, where he created a future in which the process of natural selection led to the devolution of the human species into two monstrous forms: the Eloi and Morlocks. What separated man from the animals? Was it language, as Burroughs argued in Tarzan of the Apes? Is Tarzan the common ancestor, the missing link? Or is man simply a different kind of species, sharing emotions and instincts alike, as Darwin argued in The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals? Greystoke, the 1984 adaptation of Burroughs’s novel, explored a different question: can man, a hostile and aggressive species, learn to live in harmony with the apes?

An evolutionary family romance: Tarzan, the Ape Man (1932).

[RKO/THE KOBAL COLLECTION]

The Darwinian uncanny

Sigmund Freud’s seminal essay of 1919, ‘The Uncanny’ (‘Das Unheimliche’), provides a theoretical understanding of this influential concept. In Freud’s writings, the uncanny is associated with automata, ghosts, doubling, castration, haunted houses and the undead. The uncanny is ‘undoubtedly related to what is frightening—to what arouses dread and horror’ (Freud 1975, p. 339). Drawing on his interpretation of ‘The Sandman’, a short story by ETA Hoffman, Freud argues that the uncanny is primarily related to castration anxiety. He places significance on the threat of loss—loss of one’s eyes, severed limbs, the castrating father, death. He is particularly interested in defining the circumstances in which the familiar (heimlich) becomes unfamiliar (unheimlich) or frightening—a process considered essential to the uncanny. He is also taken with Schelling’s definition of unheimlich as ‘the name for everything that ought to have remained ... secret and hidden but has come to light’ (p. ix). Repression, Freud argues, is the basis of the uncanny; that which should have been repressed emerges into consciousness. Theorist Rosemary Jackson argues that this gives the uncanny an ideological or ‘counter cultural edge’ (Jackson 1981, p. 69).

Although Darwin himself did not directly refer to the uncanny, his writings on evolution invoke the uncanny at every stage, contributing a new dimension to our understanding of this important concept. What could be more uncanny than a theory of human evolution, which completely unsettled all known stable categories of thought? A theory that caused the human subject to be forever tied to his secret double—the common ancestor that brought him into kinship with the ape? The Darwinian uncanny made the human species strange to itself. Nicholas Royle’s description of the uncanny applies with particular relevance to this discussion: ‘It is a crisis of the natural, touching upon everything that one might have thought was “part of nature”: one’s own nature, human nature, the nature of reality and the world’ (Royle 2003, p. 1). Royle also sees the uncanny as bringing about ‘another thinking of beginning: the beginning is already haunted’ (p. 1). This account is particularly relevant to the Darwinian uncanny. Darwin caused humanity to rethink its beginnings, ‘already haunted’ by a ghost of itself, by an ancient primitive ancestor that testified to the continuity of species. Darwin himself carried this troubling knowledge with him always and wrote about evolution in his secret notebooks (Browne 1995, p. 11). His theory brought to light what many believed should have been kept hidden. His writings were highly controversial, which endowed the Darwinian uncanny with a pronounced ideological edge.

The uncanny is essentially that which is both familiar yet unfamiliar, that which is different and strange. As Royle demonstrates, Freud was the first to reveal the distinctive nature of the uncanny as a feeling of something not simply unusual and odd, but strangely familiar. Darwin was constantly in search of differences and anomalies, and used the term strange repeatedly through The Origin of Species to signify anything that might offer evidence of his theory. The cuckoo possesses ‘strange instincts’ (Darwin 2003, p. 707); the male bird of paradise performs ‘strange antics’ before the females (p. 607); variations in nature and in the domestic sphere can be ‘strange’ (p. 600); aspects of the human digestive system are ‘strange’ (p. 686); the production of hybrids offers a ‘strange arrangement’ (p. 739); species spread into new territories because of ‘strange accidents’ (p. 788); vegetation grows with ‘strange luxuriance’ at the base of the Himalayas (p. 828); the condition of rudimentary, atrophied or aborted organs is ‘strange’ (p. 884); nature is filled with ‘so many strange gradations’ (p. 890); and species abound with ‘strange’ habits and structures (p. 899). Frequently Darwin describes the unusual acts he observes in nature as ‘strange’ in themselves: ‘How strange are these facts!’ (p. 614). He even describes a certain anomaly as ‘a strange anomaly’ (pp. 616, 809), indicating that some are even more abnormal or incongruent than others. The Darwinian uncanny, however, does not arise simply from the juxtaposing of familiar and unfamiliar.

Darwin’s method is to seek and identify variations—that is, traits or structures that stand out because they render the familiar individual (of a particular species) unfamiliar or strange. Such a trait might even make the individual appear incongruous or monstrous. In his discussion of inheritance and structural deviations in humans, he describes cases of ‘albinism, prickly skin, hairy bodies’ as ‘strange and rare’ (Darwin 2003, p. 547). He is constantly alert to the appearance of ‘occasional and strange habits’ in species as a way of identifying those characteristics ‘which might, if advantageous to the species, give rise, through natural selection, to quite new instincts’ (p. 703). The concept of the ‘strange’ is central to Darwin’s continuous search for variations in all species; it is variation that is the basis of natural selection: ‘I have called this principle, by which each slight variation [of a trait], if useful, is preserved, by the term Natural Selection’ (p. 61). ‘Several cases also’, he observes, ‘could be given, of occasional and strange habits in certain species, which might, if advantageous to the species, give rise, through natural selection, to quite new instincts’ (p. 703). The problem for discerning such changes in domesticated species is familiarity: ‘Familiarity alone prevents our seeing how universally and largely the minds of our domestic animals have been modified by domestication’ (p. 705). Darwin, however, is always alert to the strangeness of both wild and domesticated or familiar species. His insistent focus on the appearance of strange variations in nature is central to his writings.

In her fascinating book Beasts of the Modern Imagination, Margot Norris draws attention to the uncanny effects of Darwin’s focus on the role of variation in the processes of natural selection: ‘Darwin’s attention to monstrosity, excess, and incongruity makes his universe exceedingly strange and alienating to the modern as well as to the Victorian mind’ (1985, p. 42). Darwin’s fascination with the strange and uncanny in The Origin of Species is also reflected in his writings on monstrosities. ‘In monstrous plants, we often get direct evidence of the possibility of one organ being transformed into another’, he observes (Darwin 2003, p. 873), an idea that HG Wells explores in The First Men in the Moon (1901), in which the space travellers witness one of the monstrous Selenite species transform an ear into an eye. The other crucial thing about the uncanny is that it is not just something that is unusual or strange but that which lacks stable boundaries. It is the possibility of one thing evolving into another that was central to Darwin’s writings. Darwin’s theory of evolution and his methodology of identifying incongruity created a Darwinian form of the uncanny that also drew on a blurring of boundaries between human and animal. This new evolutionary interpretation of the uncanny was central to fin de siècle culture.

A cinematic bestiary

The evolution of the modernist cinematic bestiary owes much to Darwin’s writings on transformism and monstrosities. Since its beginnings, the cinema has specialised in horrific tales of the uncanny or unheimlich Other: giant apes, monsters, dinosaurs, werewolves, vampires, and other alien creatures. A number of these creatures, such as the werewolf and apeman, owe their physical form and definition to their origins in film. In addition, many films depict these creatures with a degree of compassion, and endow them with intelligence, so that we often sympathise more with the creatures than with their human counterparts. Compared with the latter, some even exhibit a stronger moral sense, so it cannot be said that they are in any way inferior or less evolved. Such an approach is essentially Darwinian. In The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals, Darwin also destabilised the major distinctions between human and animal, maintaining that the emotional, moral, intellectual and cultural differences were a matter of degree rather than of kind. The monstrous creatures of the cinema are essentially uncanny in that they embody both human and non-human characteristics. It could be argued that the cinema has created an imaginary space—a Darwinian space—in which audiences are encouraged to view the world from the standpoint of the animal, to collapse the boundary between human and animal in order to see through animal eyes or to ‘become’ animal (see chapters 8 and 9). Such a stance was central to Darwin’s own methodology; in his journals he recorded how he tried to think and feel as if he were an animal or insect (Norris 1985, p. 34).

Darwin’s thesis about evolution and the relationship between humans and animals has, over the decades, inspired the many uncanny human–animal hybrids of science fiction literature. One of the most popular of these works is HG Wells’s satiric novel The Island of Doctor Moreau (1896), which explores the dark side of evolutionary thinking, and which has engendered at least five screen versions. These include the remarkable Island of Lost Souls (1932), which starred Charles Laughton; a 1977 remake, The Island of Dr Moreau, with Burt Lancaster; and the more recent 1996 version starring Marlon Brando as the fabled doctor. Wells’s tale is a savage indictment of human nature, with its narrative of the mad doctor who uses vivisection to transform animals into human beings in an attempt to advance evolution. Deluded by his own grand ambitions, Moreau only succeeds in creating uncanny ‘beast-people’, monstrous human–animal hybrids who eventually succumb to the onslaught of devolution as the ‘stubborn beast flesh grows day by day back again’ (Wells 1993 [1896], p. 113). The monsters are made to repeat a chant to Moreau, their god, affirming that they are indeed men and must not behave as animals. When the novel’s hero returns to London, he looks at his civilised fellows but can only conclude that the ‘animal was surging up through them’ (p. 128).

Darwinian theory allowed for the possibility of reversal.4 Just as the human subject might evolve towards a higher, superior life form, it might just as easily devolve into a lesser, abject species. This possibility was further complicated by the fact that devolution was supposed to affect human beings differently. Popular writers of the day—such as Cesare Lombroso, the Italian criminologist—argued that women, children and indigenous people were more likely to devolve than to evolve, particularly if their lives were not subject to the educative and morally uplifting guidance and control of a husband or patriarchal father figure. As various writers point out, fin de siècle culture became obsessed with the idea of devolution or degeneration, a concept that early cinema explored from the very beginning with its narratives of transformation and metamorphosis in which both human and animal devolve into lower forms of life. The category of horror film that appears to be almost entirely devoted to the question of devolution is the werewolf film. Here the visual and narrative emphasis is placed on the concept of the divided self, in which the wild animal eventually wins out over the civilised human.

Devolution and desire

Darwin’s book The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals, published in 1872, demonstrates his clear intention of drawing connections between human and animal. His aim was to reveal parallels between human and animal in the expression of feelings in order to show that not just the body but the mind also is a product of evolution. Darwin supported his argument with reference to photographs and drawings that demonstrated similar emotional expressions on human and animal faces. It was one of the first scientific works to use photography to support scientific arguments. Darwin’s focus on the evolution of the same emotions in human and animal lent further support to the possibility of devolution. Although Darwin himself did not engage directly with the discourse on devolution, a number of his followers did. E Ray Lankester argued that if it was possible to evolve, it was also possible to devolve, and that complex organisms could devolve into simpler forms or animals (Danahay 2005, p. 20). Others, such as Lombroso, were more interested in the possibility of a kind of moral or ethical devolution. Lombroso went so far as to argue not only that criminals possessed different brains from those of the law-abiding but also that the criminal type was a kind of throwback to a more primitive human being.

The poss...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 Darwin, early cinema and the origin of uncanny narrative forms

- 2 Darwin’s pre-cinematic eye: evolution and metamorphosis in Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde

- 3 The future of evolution: science fiction, deep time and alien species

- 4 Evolutionary aesthetics: the Hollywood musical as Darwinian mating game

- 5 The Darwinian gaze: sexual display, sexual selection and the femme fatale

- 6 Devolutionary aesthetics and the early detective film: in search of the ‘missing link’

- 7 The unheimlich Pacific of popular film: Darwin’s surreal imagination

- 8 What do animals dream of? Or King Kong as Darwinian screen animal

- 9 A Darwinian love story: Oshima’s Max Mon Amour

- References

- Index

- Copyright