![]()

Chapter 1

A nation of cities

IN AUSTRALIA WE BELIEVE many myths about our country. We think we are laid-back, but we work some of the longest hours in the world. In the spirit of Ned Kelly, we think of ourselves as anti-authoritarian, yet we comply with seatbelt and bicycle helmet regulations, and nearly all of us vote in elections, as the law requires.

When we Australians portrayed ourselves to the world in the opening ceremony of the 2000 Sydney Olympics, we chose 120 stockmen and women dressed in bush clothing and riding horses to the movie soundtrack of The Man From Snowy River. Similarly, all but one of the thirty-nine drawings in the Australian passport depict flora, fauna and outdoor recreation, while the thirty-ninth is an outback pub. Citizens of one of the most urbanised nations on the planet carry an identity document that does not depict a single feature of any Australian city or town.

A greater proportion of Australians live in cities than nearly any other country. Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, Perth and Adelaide all have populations of more than a million. Together they house more than three in five Australians. Three-quarters of Australians live in cities with a population above 100 000, compared to 68 per cent of Americans, 71 per cent of Canadians and 62 per cent of people in the United Kingdom.

Australia’s cities date from European settlement: the first settlers landed at Sydney Cove in 1788. Subsequent permanent colonial settlements included Hobart and Newcastle in 1804, Moreton Bay (now Brisbane) in 1824, Swan River (now Perth) in 1829, Adelaide and Port Phillip (now Melbourne) in 1836.

The discovery of gold in the mid-nineteenth century transformed the Australian economy. In just twenty years the population grew from 430 000 to 1.7 million. Aside from this first—and biggest—mining boom, agriculture dominated the early Australian economy. Shortly after Federation, in 1906, almost half of Australia’s four million-strong population lived on rural properties or in small towns of fewer than 3000 people. Many were market towns serving the agricultural economy. Only about one in three Australians lived in a city of at least 100 000 people.

The legacy of our historical dependence on the bush is powerful. In 1901 a third of Australian workers were employed in agriculture, forestry, fishing or mining. Australian ingenuity—including inventions such as the stump-jump plough—made our farmers some of the most productive in the world. Until well into the twentieth century we depended on wool as our main export. The men who produced it came to epitomise what it was to be Australian.

But we are no longer a nation of farmers, graziers, shearers and drovers. The days of the economy riding on the sheep’s back are long gone. Wool is now much less important as an export, even if the phrase still evokes the importance the agricultural industry had to the country’s wealth. The volume of agricultural production continues to increase, in no small part through the increasing role of machines, and the sector is still a big exporter. But today agriculture employs only 3 per cent of the Australian workforce and contributes about 2 per cent of our national income.

After World War II came the rise of manufacturing as Australia’s dominant industry. Around 1960, more than a quarter of all working Australians worked in manufacturing. The industry generated almost a third of our income.

With the rise of manufacturing, Australia’s prosperity shifted to big cities, and often to their suburbs. Many people migrated there from rural areas, drawn by the prospect of jobs in manufacturing. By the end of Robert Menzies’ record term as prime minister in 1966, more than three in five Australians lived in cities of more than 100 000 people.

The manufacturing industry greatly influenced the layout of cities. Many manufacturers, needing large amounts of land, located their factories where it was plentiful and affordable. Suburbs away from city centres had far lower rents and less congestion. Western Sydney became Australia’s largest manufacturing region. The outer suburbs of Melbourne and Adelaide became home to many industrial plants, including car manufacturers such as Ford and General Motors Holden.

Postwar growth in car ownership made possible the shift to a manufacturing economy with a strong suburban presence. ‘It is easy to forget just how liberating the car was,’ write city planning and economics experts Marcus Spiller and Terry Rawnsley. It delivered an enormous boost to productivity by giving people access to a wider selection of jobs. ‘Skills were better matched to industry needs and workers acquired new skills more rapidly, simply because of the mobility offered by the car.’

Car ownership and dispersed employment opportunities enabled many people to build houses in what were then outer suburbs of Australia’s cities—places such as Altona in Melbourne, Silverwater in Sydney and Acacia Ridge in Brisbane. Owning a detached house on a quarter-acre block came to be known as ‘the great Australian dream’.

Growth in the manufacturing industry eventually began to decline as a proportion of the economy. In the last twenty years the number of people employed in manufacturing has broadly stood still as the nation’s economy and population have grown. Manufacturing now employs less than 10 per cent of working Australians.

More recently, the mining boom has been pivotal to Australia’s economic growth. Yet it is worth putting mining’s importance to the economy into context. Since Federation in 1901, mining has never produced more than 10 per cent of gross domestic product (GDP). Today the industry employs 2 per cent of working Australians, while the Reserve Bank of Australia estimates that the Australian mining sector is 80 per cent overseas-owned. It is much less important to the economy now than manufacturing was in the 1960s.

While Australia’s natural resource deposits are typically in remote areas, many mining-related jobs are not located in the Pilbara, the Hunter Valley or the Bowen Basin. In Western Australia, where the most productive mining regions are located, more than a third of people employed in mining actually work in Perth. These include geologists who assess mineral deposits, engineers who design mining equipment and programmers who develop mining software. All these highly skilled workers have enabled the Australian mining industry to be one of the most productive in the world.

Today, when more than three-quarters of Australians live in cities, the economy is no longer driven by what we make—the extraction and production of physical goods—but rather by what we know and do. Some of the highest recent employment growth has come from professional services such as engineering, law, accountancy and architecture, from construction—whether of housing, offices, mines or roads—and from health care to support an increasingly affluent and long-lived population. Today Australia’s fourth largest export sector is educating international students—something we barely did thirty years ago. Like other advanced economies, our economy is becoming more knowledge-intensive, specialised and globally connected. We have limited control over these trends, but they present us with many opportunities. And as with other periods in our economic evolution, this kind of economy has implications for what happens where.

Yet old notions die hard. Legacies and myths about the Australian economy keep a powerful hold on the popular imagination. The reality is that cities, knowledge and services are the engines of the Australian economy today, even if the bush and primary production still carry a certain romance. It’s probably more glamorous and exciting to think of ourselves as a nation of jackaroos or mine supervisors than deskbound office-dwellers, sales assistants or nursing-home attendants. But the facts don’t lie.

Cities generate most of our national income: 77 per cent. Big cities are especially important. Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, Perth and Adelaide together generate two-thirds of Australia’s income. Sydney alone produces around the same amount as the combined economic output of every city and town of less than 100 000 people, and all rural and remote areas, across every state and territory. To make this contribution, Sydney requires a tiny 0.16 per cent of Australia’s land mass.

Australia’s cities

Australia’s biggest cities are large even by international standards. For example, the Netherlands has a population of seventeen million, roughly similar to Australia’s twenty-three million. But its largest city, Amsterdam, is a quarter of the size of Sydney.

Australia’s five largest cities are all home to more than a million residents. Together, Sydney and Melbourne are home to about two in five Australians. This has many advantages. As we will see, large cities provide more opportunities for their residents and larger markets for the businesses operating in them.

The concentration of people in a handful of cities has deep historical roots. Unlike most countries, in Australia towns were created first, and rural populations followed. Instead of emerging slowly from farming communities, our cities began as administrative bases for the colonies.

Although they have similar beginnings, Australian cities differ on many dimensions, from size and shape to demography and climate. Sydney has almost three times the population of Perth. The typical family in Canberra earns roughly 60 per cent more than the equivalent family in Hobart. Sixteen per cent of Adelaide’s population is over sixty-five, compared to 6 per cent in Darwin.

In the thirty years to 2013, Australia’s population grew by almost eight million people. Population growth comes from the number of children people have. It also comes from immigration. Natural increase (births minus deaths) and net migration (people arriving in Australia minus people departing) both contributed about four million new residents to Australia across this period.

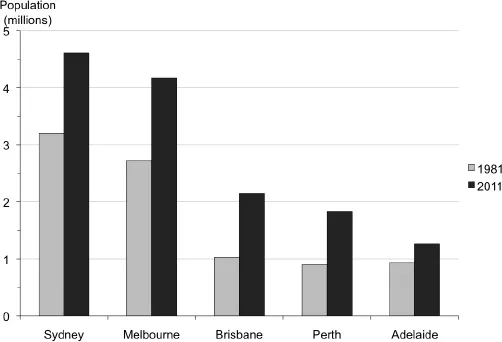

Most of Australia’s population growth happens in cities, with their greater opportunities for employment and for connecting with other people. Figure 1.1 shows how the size of Australia’s five largest cities has grown between 1981 and 2011.

Figure 1.1: Population of Australia’s five largest cities, 1981–2011

Australia’s large cities also have diverse populations. One in four residents speaks a language other than English at home. One in three was born overseas.

Why people live in cities

Living in a city with many other people has many benefits. One of them is scale. The more people who come together, the more that businesses and employees can specialise. Pooling lots of people’s needs and wants creates many opportunities to specialise in meeting common needs. The large populations of cities offer more sellers and buyers, looking to buy and sell more things.

When lots of people own cars, for example, different mechanics spring up. All compete with each other to earn income from customers. Some might expand to offer services across the city, offering consistency wherever customers live. Repco boasts about thirty authorised service centres in Brisbane, and KMart Tyre and Auto Service around the same. Others run more boutique businesses, providing customised services. Memory Lane Classic Auto Restorations in Perth specialises in repairing classic automobiles and vintage cars. Still other mechanics might make convenience their point of difference. Lube Mobile has offered services at their customers’ homes since 1982.

A critical mass of mechanics means that suppliers of equipment such as hoists and car parts are more likely to do business in that city. The mechanics themselves benefit from more choice and lower prices as suppliers compete for their business. In cities with large populations, these kinds of benefits snowball across the economy.

Competition between mechanics drives prices down and gives customers more choice. People who want jobs as mechanics also benefit, as they can specialise in the kind of work that fits best with their own skills and interests.

Cities also make it possible to specialise in meeting more niche needs. For example, there is enough demand among chess-playing Melburnians to sustain a dedicated chess supply shop. Chess World is the kind of niche business that wouldn’t be viable somewhere with a small population.

The diversity of needs and wants across cities’ large populations makes it more likely that individuals can find work that makes the most of their abilities and experience. For example, the job market in Sydney, our biggest city, is extremely diverse. Cleaners, plumbers, manicurists, scientific researchers and senior executives of multinational companies can all find plenty of job opportunities. The Australian Bureau of Statistics divides the Australian job market into 474 kinds of role, encompassing everything from outdoor education guides to sales assistants, truck drivers and nurses. There are people doing 473 of these kinds of jobs in Sydney. The only group missing is aquaculture workers. So if it’s possible to do something for a living in Australia, there’s a very good chance you’ll be able to do it in Sydney. Cities give people more choices.

Sydney’s job market is also very deep. Its two million workers span many employers: sole traders; small, medium and large businesses; charities and government agencies. Not all of them will be hiring at any particular time. But the depth of the job market increases the likelihood of there being at least one employer looking to hire someone with any given set of skills.

Almost all migrants to Australia—85 per cent—settle in a city of more than 100 000. Half of them settle in Sydney or Melbourne. One of the reasons they do so is to maximise their chances of finding a job that makes the most of their skills and experience.

The number and range of needs and wants in cities—especially large ones—give people an incentive to train and develop their skills. Becoming an engineer requires four years of full-time study. Students are unlikely to undergo the long years of training—paying considerable fees and forgoing income they could otherwise be earning—unless they are reasonably confident there will be a demand for their engineering skills when they finish their degree. A large city is more likely than a small town to have enough demand for engineering services to justify students learning these skills. This is even more the case in specialised fields such as software, electronic or hydrological engineering.

In turn, universities, TAFEs and colleges are needed to enable people to develop their expertise. These institutions are more likely to flourish in places with sufficiently large populations to create the demand for the skills they teach, and from which they can recruit experts to provide the training they offer.

As a result, many people stay in cities and move to cities. They provide opportunities: to get a job, to get a better job, to start a business or to build skills.

After finishing school in Ballarat, Cameron Harrison completed an economics degree down the road in Geelong, but there was little local demand for the specialised economic modelling and analysis skills he had learned. He moved to Melbourne and found a job in the public service, helping to provide economic advice to the Treasurer.

Cameron’s experience of moving to a large city to make the most of his skills is not unusual. Nor is moving to a larger city to develop those skills in the first place. In Ballarat, fewer than one in five people have a university degree, and the average income is about $50 000 a year. Melbourne’s larger population creates much more demand and reward for more specialised skills. The financial pay-off from making the most of your skills in a big city can be substantial: the average income in Melbourne is almost a third higher than in Ballarat.

Cities also make it easier for households in which both partners want to work. They make it possible for each partner to get to jobs that best utilise their skills. There are simply more jobs and a broader range of jobs available.

The breadth and depth of city job markets also make it easier for people to bounce back if they lose their job. Cities also offer more opportunities for a person to find a better job than their current one. In rural areas, with smaller numbers of employers and ranges of jobs available, it can be much harder for people to find another job if work in their own industry is drying up.

At the start of 2014, SPC Ardmona’s parent company, Coca-Cola Amatil, foreshadowed that ...