- 493 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

It contemplates why these agreements were forged, how the Aboriginal people understood their terms, why government repudiated them, and how settlers claimed to be the rightful owners of the land.

Bain Attwood also reveals the ways in which the settler society has endeavoured to make good its act of possession—by repeatedly creating histories that have recalled or repressed the memory of Batman, the treaties, and the Aborigines' destruction and dispossession—and charts how Aboriginal people have unsettled this matter of history through their remembering.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Possession by Bain Attwood in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART 1

CONTESTING SOVEREIGNTY

1

CONSIDERING A TREATY

On the face of it there was nothing exceptional about the treaty that has come to be known as Batman’s treaty. Since the fifteenth century European powers had concluded treaties with non-Christian peoples; throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries they had made agreements with indigenous peoples in South and West Asia, North Africa and North America; and during much of the nineteenth century they continued to treat with indigenous peoples in North America, Africa and the Pacific. Indeed, there were hundreds of such treaties. It could even be argued that treaty-making was the norm.

Yet this treaty was unusual. In legal terms, it was, strictly speaking, just a contract for the purchase of land; in most parts of the British Empire such transactions were not commonly called treaties, and where they had been, as in the American colonies, they were usually made by official representatives of the British Crown rather than by private individuals, as was the case with ‘Batman’s treaty’. In political terms, this conveyancing deed, which was first called a treaty by its own makers, was even more remarkable; whereas many colonisers elsewhere in Britain’s far-flung empire had made agreements to buy the land of the indigenous peoples in an attempt to acquire title, it seems no such arrangements had ever been made in its Australian colonies. In other words, this treaty does present something of a historical puzzle: why did those responsible for it seek to purchase the Aboriginal people’s land when their fellow colonisers and the imperial and colonial governments had merely taken possession of the land as though it had no owners, and why did they represent their deed as a treaty?1

The answers to these questions can be found by recovering both the colonial context, especially that of Tasmania, or Van Diemen’s Land, as it was called then, and the imperial or Anglophone context, especially that of North America, in which these colonisers acted. In doing so, we will see that a considerable range of factors lay behind the treaty that Batman purported to have made with the Woiworung, the Bunurong and the Wathaurung people in Port Phillip, or what became Melbourne, in 1835.

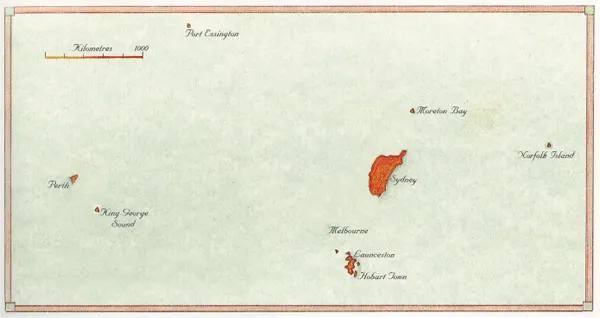

THE PORT PHILLIP ASSOCIATION

To begin, the spatial context of this story must be made clear. This map (see below) shows the extent of white settlement at the time. It comprised a small population, numbering in the tens of thousands, scattered over a vast continent and a couple of islands. The historian Alan Atkinson has described these colonies as the Australian archipelago, a chain of small islands of settlements in the southeast that included much of Van Diemen’s Land, and a cluster of pinpoints centred on Swan River (or what became Perth) and King George Sound in the west. This was all there was. The first Australian colony, New South Wales, founded in 1788, consisted of the surveyed nineteen counties, a half-circle at a hundred-mile radius from Sydney. This was called the ‘Limits of Location’—to ‘locate’ meaning to possess or take possession. This was commonly regarded as the limits of the colony and of the Governor’s authority, although, technically speaking, New South Wales included all of the eastern two-thirds of the continent. In 1835 the New South Wales Surveyor-General, Sir Thomas Mitchell, exploring the area outside the limits, spoke of having left the colony as soon as he reached the unsettled territory beyond it, and had the sense that he and his companions were ‘rather unceremonious invaders of their country’, ‘their’ meaning the Aboriginal people. The British had sought to plant a colony at Port Phillip Bay towards the end of 1803, but they had departed by the beginning of 1804 to colonise Van Diemen’s Land. Now, however, settlers there, looking across Bass Strait, were inclined to imagine that this corner of the mainland was beyond the reach of the British Empire, or at least the colonial government in Sydney, because it was so far from the territory over which its authority effectively ran. Distance has been important in Australian history. It has often been called a tyranny. But in this case it gave the group of propertied individuals comprising the Port Phillip Association a sense of autonomy, which, as we will see, extended to the arrangements they might make with the indigenous people.2

The limits of the British Empire. At the time the men of the Port Phillip Association contemplated their colonising venture in Port Phillip Bay, the only parts of the Australian colonies that were really in the possession of the British Crown were those marked red on this map. To them, Port Phillip, marked by Melbourne on this map, seemed far beyond the authority of the Governor of New South Wales in Sydney.

The Association’s treaty-making has often been cast as a frivolous and foolhardy gesture by the colonisers who proposed it, most recently by the historian AGL Shaw. This loses sight of several crucial matters: the nature of sovereignty, especially in borderland or frontier zones such as this; the influence of imperial and local precedents for such land-grabbing; and the influence of evangelical Christian narratives about the costs of colonial wars. But before we consider these in any depth, something needs to be said about the men responsible for considering what they called a treaty.3

The purchase of Kulin land was proposed by a group of men, most of whom were in their thirties or forties, who formed themselves into a corporation soon after the making of the ‘treaty’. Most commonly, they called it the Geelong and Dutigalla Association (for reasons that will be discussed shortly), but it has come to be known as the Port Phillip Association. It comprised Henry Arthur, Thomas Bannister, John Batman, John Thomas Collicott, Michael Connolly, Anthony Cotterell, Joseph Tice Gellibrand, George Mercer, John and William Robertson, William George Sams, James Simpson, John Sinclair, Charles Swanston and John Helder Wedge. All but one of these men lived in Van Diemen’s Land, and most of them had done so for some time, although Swanston had experience of India, having served in the British East India Company there, and Bannister had experience of other Australian colonies, having led an expedition between Swan River and Albany in King George Sound. (Mercer, a Scot who had served in the British East India Company before selling his commission to become a merchant in Calcutta, was based in Edinburgh but had become acquainted with Swanston during his time in the British East India Company’s employ.) As we will see, the reasons for the Association’s treaty cannot be grasped unless this common Van Diemonian background is appreciated. It is difficult to conceive a similar group of men in the other major Australian colony in this period, New South Wales, treating with Aboriginal people, at least at this time.4

Nearly all the Association’s members belonged to respectable society in Hobart or Launceston, the largest towns in Van Diemen’s Land. Even the native-born Batman, who probably had the lowest social standing of any member of the group owing to his convict background, was held in some regard by the Governor. A few of them belonged to the colony’s small governing elite or were closely acquainted with its principal administrators; many were, or had been, public servants; and several held or had held positions of considerable responsibility: Arthur, nephew of the Governor, Sir George Arthur, was a customs officer and a Justice of the Peace; Bannister, the brother of Saxe Bannister, once the Attorney-General of New South Wales, had been private secretary to Arthur and was Sheriff of Hobart; Collicott was Postmaster General and a Justice of the Peace; Cotterell was a chief constable; Gellibrand had been Attorney-General; Sams was Deputy Sheriff of Launceston; Simpson was a police magistrate and commissioner of the Land Board; Sinclair had been an engineer and was Superintendent of Convicts in Launceston; and Wedge was a surveyor. Furthermore, several members of the Association, such as Connolly and the Robertson brothers, were merchants, financiers, businessmen or pastoralists of considerable substance. Swanston, as chairman of the Derwent Bank, was an especially prominent figure in this regard. Some of these men invested a considerable amount of capital in a venture in which the purchase of Aboriginal land was central. Moreover, the men who were really important in the Association’s affairs, namely Bannister, Batman, Gellibrand, Swanston and Wedge, represented what has come to be regarded as the most critical components of knowledge and power in colonising at this time—geography (Wedge), law (Gellibrand), Christianity (Bannister), commerce (Swanston) and ethnography (Batman)—and they were familiar with current humanitarian ideals regarding Aboriginal people. All this might suggest that the nature of the group’s approach to colonising Port Phillip was informed by a greater degree of reason than historians have customarily attributed to it, although we should be wary of making too much of the role of reason when we are contemplating the chaotic world of the colonial frontier since the line there between reason and unreason or the fantastic and the real tends to be very thin.5

In many of the critical historical accounts of the treaty-making, Batman has been cast as the key figure, but this distracts us from the fact that several of the Association’s principal members played a more important role in the decision to treat with the Aboriginal people for their land. Batman was the major player in the enactment of the Association’s treaty at Port Phillip (as will be seen in chapter 2), but Wedge was almost certainly responsible for recommending this instrument of colonisation to the Association’s members in the first place; Bannister probably had a major hand in persuading the other members of the Association to make the gesture to buy the land; and Gellibrand undoubtedly planned the Association’s strategy for possession around the treaty and had the conveyancing deeds made up.

A MATTER OF SOVEREIGNTY

The men of the Port Phillip Association knew what they wanted. British demand for wool in the 1820s had made good pastoral land scarce and costly in Van Diemen’s Land, so they were looking for another place to invest their surplus capital and make a fortune for themselves or their children. Port Phillip seemed to fit the bill nicely. However, they were unsure how they might realise their goal.

Just a few years previously, the imperial government had introduced new rules to regulate the disposal of land. Until the early 1830s it had accepted that land could be administered locally rather than centrally, and colonial governments had given an enormous amount of land to settlers and servants and friends of the government, on the basis of their rank and loyalty and the amount of capital they had. However, the imperial government had come to be influenced by classical economists like David Ricardo and Thomas Malthus, and systematic colonisers like Edward Gibbon Wakefield, who argued that an approach to land that was oriented to revenue would benefit colonial development and government, and by evangelical Christians, who expressed concerned about the plight of indigenous peoples on the frontiers of settlement. At the same time, it wanted to limit the costs of maintaining armies in its colonies. Consequently, it called on its colonial governors to restrict the spread of settlement. In the case of New South Wales, settlement was to be prevented outside the limits of location, and all Crown land had to be sold (at auction with a minimum price of purchase set higher than market value) rather than given as free grants or taken by squatters.6

Many aggressive colonisers sought to defy these new rules (which were known as the Ripon Regulations), and land-grabbing became endemic. In 1834 settlers expanded dramatically beyond the limits of location, occupying immense tracts of land in western and northern New South Wales. In doing so, these land-grabbers devised various ruses to acquire land titles and avoid the liabilities incurred by their illegal seizure. Their principal method, however, was possession or squatting. By simply occupying Crown land they hoped to acquire a legal interest. This reflected a claim that possession was nine-tenths of the law, a peculiarly English notion that was given new life on the colonial frontier. The men of the Port Phillip Association could have simply adopted this blatant manner of contesting the government’s authority, but they chose to do more. They wanted to present themselves as being more law-abiding than other land-grabbers, and they wished to clothe their attempt to grab land in a particular legal form. Gellibrand’s legal training probably played a part.7

More than this, however, it seems that these men required the resource of the law in an intellectual sense in order to be able to imagine for themselves the very act of colonising Port Phillip. In 1827 Batman and Gellibrand had applied to the Governor of New South Wales, Ralph Darling, for a land grant near Western Port, southeast of Port Phillip Bay, but he had refused their request (because he was contemplating the abandonment of the settlement his government had founded there the previous year in order to counter a possible French threat to British sovereignty). Thus, in the minds of these aspiring colonisers, the principal obstacle to their wish to grab land was the New South Wales government’s assertion of authority over this area. In their minds this meant they had to conceive of a way of challenging the sovereignty asserted by the New South Wales government over this territory, which is to say that they had to envisage an alternative source of authority for it, whether that be the Governor of Van Diemen’s Land (as an agent of the British Crown) or the Aboriginal people of Port Phillip. The former did not necessitate the making of a treaty (although it recommended this stratagem), but the latter did. Indeed, the act of recognising, or at least pretending to recognise, the Aboriginal people as sovereign was one of the principal reasons why the Port Phillip Association considered making a ‘treaty’. As a commonly acknowledged symbol of sovereignty, an instrument called a treaty provided a legal mechanism that enabled these men to foresee a relationship between themselves and the land they wanted to possess but which was under the jurisdiction of an authority that had barred their colonising venture. Thus, what the members of the Association chose to call a treaty allowed them to conceive, rather than merely justify, their attempt to appropriate the land at Port Phillip.8

In September 1834 Wedge and some of the other men of the Port Phillip Association got wind of the plans of another party based in Van Diemen’s Land, the Henty family, to seek permission from the Colonial Office to purchase land at Portland Bay, west of Port Phillip Bay, where they had been engaged in whaling for several years. (Shortly afterwards, the Hentys sent a vessel across Bass Strait to take possession of land there.) As a result, they seem to have decided that they would try to test the legal validity of a proposal to purchase land from the Aboriginal people of Port Phillip. In a disingenuous letter to Governor Arthur, they concocted two fictions: first, they claimed that a party of individuals (the Hentys) had proposed to take possession of a tract of country at Portland Bay by making a treaty with the Aboriginal people and, second, they alleged that another such party had taken possession of a considerable tract of country in the vicinity of Twofold Bay, a few hundred miles south of Sydney, by simply negotiating a purchase with the Aboriginal people. In the first case, Wedge and his associates were presuming that the area of Port Phillip might not be deemed to lie within the jurisdiction of New South Wales and could instead be claimed by Van Diemen’s Land on behalf of the Crown; in the second, they were assuming that an area such as Twofold Bay, which lay beyond the limits of location, would be held to lie within the jurisdiction of New South Wales.9

It is possible that Governor Arthur had actually encouraged Wedge to raise the matter of jurisdiction (for reasons to be considered shortly) since the two men had recently conversed about the possibility of an expedition to explore the interior of the continent of Australia. At any rate, Arthur referred this to his Solicitor General, Alfred Stephen. At first, the legal opinion Stephen gave seems to be unambiguous: Portland Bay or Port Phillip Bay lay within the jurisdiction of the Governor of New South Wales; therefore Arthur as the Governor of Van Diemen’s Land had no right to try to possess this country. Yet this would not have surprised the men of the Port Phillip Association. They already knew this to be the claim of the New South Wales Governor. They also knew that this did not go to the heart of the matter. What Stephen had to say next did, since he drew attention to the significant disjunction that commonly existed between the claims of government to be sovereign in a borderland or frontier zones of a territory and the actual operation of its jurisdiction on the ground in that area (just as it reflected the fact that the nature of the government’s sovereignty at this time was in a state of transition as it was being increasingly defined by it in a much more territorial sense rather than a jurisdictional one, a crucial matter that will be discussed in chapter 3). Stephen advised Arthur: ‘I find that some years ago, the Government of N. S. Wales fixed the Southern boundary of the Colony, for purposes of settling, at a point which excluded Twofold Bay. I apprehend that such an order, referred only to the authorised occupation of land; and that the boundaries of the Government, as defined by the King’s Commission remain just where th...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- PART 1 CONTESTING SOVEREIGNTY

- PART 2 LEGEND MAKING

- PART 3 REMEMBERING HISTORY

- Abbreviations

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index