![]()

CHAPTER 1

Beginnings

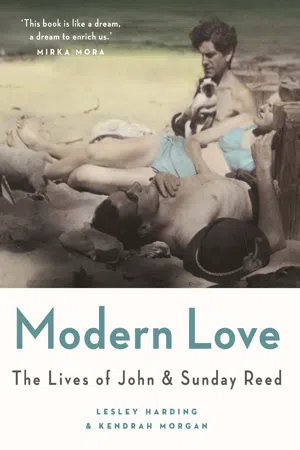

BOTH JOHN AND Sunday were born into establishment families founded in Australia two generations previously. Each had paternal grandfathers of humble origins who came to the Antipodes as young men ready to make their names and fortunes. Henry Reed senior and James Baillieu arrived in 1827 and 1853 respectively and proved prodigious—Henry became one of Tasmania’s most enterprising pioneers, astute businessmen and great philanthropists, while James produced a Victorian dynasty and set the wheels in motion for the Baillieus’ remarkable commercial success and social prominence.

John invariably avoided mention of his family history, claiming to have little interest in it.1 Though he summarily dismissed his grandfather, Henry Reed was in fact a determined, ambitious and entrepreneurial man, with an exceptional capacity for hard work and charitable deeds. John regarded himself as utterly unlike his puritanical predecessor, yet he did inherit his grandfather’s qualities of fortitude, perseverance in the face of all odds, and strong sense of noblesse oblige.

Henry senior was the son of a Yorkshire postmaster, and arrived in Hobart Town, Van Diemen’s Land, as it was then known, in April 1827 at the age of twenty. He secured a clerk’s position in a mercantile business in Launceston and befriended John Batman—the future founder of Melbourne.2 He then acquired a free land grant of 640 acres from Lieutenant-Governor George Arthur in early 1828, the first of his many properties.Henry’s fortunes continued to rise as he established his own operation as a merchant and purchased a small fleet of ships, commencing a series of whaling, sealing and general trading ventures between Launceston, Hobart, Sydney and London. Following two miraculous survivals aboard ships that seemed destined to sink, he was convinced that God had called him. After marrying his cousin Maria Susanna Grubb in London in 1831 he travelled between England and Tasmania, and became a devout Wesleyan and lay preacher.

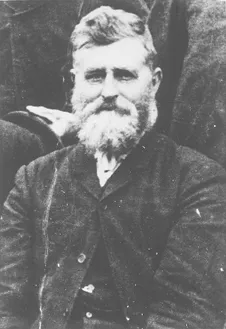

Henry Reed senior, John’s grandfather c.1875

In 1835 Henry assisted John Batman’s settlement of Port Phillip, lending Batman £3000 and bringing migrants and supplies from Launceston. Henry also delivered the first sermon ever to be heard in Melbourne—or so he claimed—to John and Henry Batman, William Buckley and three Indigenous men.3 He then travelled up the Yarra River into the ‘wilderness’ with members of the Yarra Yarra tribe, probably with their conversion in mind.4 In all likelihood the group passed by the very site on the riverbanks at present-day Bulleen where John and Sunday would establish their home, Heide, exactly a century later.

With the end of the first pastoral boom and an Australia-wide depression in the 1840s Henry settled again in England in 1847, in Harrogate, Yorkshire, and devoted himself to preaching and philanthropy. Following the death of Maria in 1860 he married Margaret Frith from Enniskillen, Ireland, who was equally pious. With Margaret, Henry had five children, adding to the eleven he had fathered with Maria. The youngest was John’s father, Henry junior, born in 1870 in Tunbridge Wells, West Kent, where the Reeds had moved.

Henry’s final return to Tasmania was in late 1873, where he and his second family resided at Mount Pleasant, a magnificent hilltop property with panoramic views across the Tamar River and Launceston. In 1875 he gave support to Methodist missionary Dr George Brown to found the New Guinea Mission and came to acquire several Sepik River artefacts which, together with four John Glover landscape paintings, were, to John’s mind, the only artworks of note to grace the interior of the Mount Pleasant residence. Henry died at home on 10 October 1880 and was buried in the family tomb on the grounds.

Henry left an entailed estate in the age-old English tradition, with the assets passing to the eldest son, while the other offspring received a settlement.5 Walter, his eldest son with Margaret, should have received the principal inheritance, as Henry’s surviving sons from his first marriage were—for no clear reason—not taken into consideration. However, young Walter proved himself the black sheep of the family; he fell in love with a girl of convict stock well beneath his station6, and would eventually die tragically young in a brothel in London under mysterious circumstances. His name was never mentioned in the Reed household when John was growing up and Cynthia suspected that her own difficult relationship with her father may have stemmed in part from her close physical resemblance to her renegade uncle.7 Henry Reed’s vast estate thus passed to Henry junior, who was just ten years old at the time of his father’s death. Henry senior had left instructions for his wife about the boy’s education and upbringing in Tasmania, but Margaret disregarded her late husband’s wishes8 and in January 1882 took her son, together with his siblings, back to England.

Henry junior went on to study medicine at Cambridge and remained abroad until 1892, when it became evident that the matters of his father’s estate were in complete disarray.9 Another depression had struck Australia in 1890 as overseas investors withdrew their resources when financial returns proved less than anticipated. To his displeasure, Henry was forced to return to Launceston to take over the running of the Reed interests. He had no business experience and no great love for life on the land. In his favour was his extremely methodical nature, which, along with sound accounting skills, enabled him to be a very careful manager. John would inherit his self-discipline, analytical capabilities and exacting attention to detail.

After three challenging years Henry turned twenty-five and came of age, gaining independence from the trustees. He proposed to Lila Borwick Dennison, a raven-haired beauty from the Orkney Islands, Scotland, whom he had met in England, and they married in Bakewell, Derbyshire, in July 1895 after which Henry took his bride home to Australia. After the cool climes of her homeland, Lila had difficulty adjusting to the harsher conditions of Tasmania. Despite her humble Scots background, she affected to be more English than the English and abhorred the slovenly speech and informality of the locals.10 John’s own refined diction as an adult had surely been drilled into him by his mother.

Henry Reed, John’s father c.1910

Lila Reed (née Borwick Dennison), John’s mother c.1900

John Harford Reed c.1910

Henry and Lila initially lived at Fairview, in High Street, Launceston, where their first child, Coralie, was born in June 1896, then moved to Logan, Evandale, a pastoral property that the trustees had bought in the 1880s. Here their five other children were born: Henry, known as Dick, then Margaret, John, Barbara and Violet, always addressed by her middle name, Cynthia. John Harford Reed arrived on 10 December 1901 and grew into a dark-haired, fine-looking boy, very like his attractive mother. His abundant wavy locks caused his siblings to nickname him Paderewski, after the Polish prime minister and brilliant concert pianist of the era who sported a wild mane of hair. To his parents, however, he was known simply as Jack.

__________

Unlike John, Sunday remained proud of her family lineage. Born on 15 October 1905 across Bass Strait, in Melbourne, Victoria, Lelda Sunday Baillieu was an heiress to a family whose enterprise and influence would help shape the face of Melbourne. She could trace her ancestry to the French-speaking Catholic Baillieux family who were embroiderers and mercers in late-eighteenth-century Liège, and enjoyed telling friends that she belonged to a long line of lace-makers.

Sunday’s direct ancestors, among the Belgian Baillieux, were actually professional dancers. Her great-great grandfather Etienne Lambert Baillieux (known as Lambert) immigrated to England in 1792 and completed his dancing apprenticeship in Bath before taking up a teaching position. Within a few years he had anglicised his surname by dropping the ‘x’, converted to Anglicanism, settled in Bristol and married Ann Taylor, with whom he had three children.

Lambert’s eldest child and namesake, Lambert Francis Baillieu, became a dance and music teacher in the market town of Haverfordwest in Pembrokeshire, Wales. There he met and married Elizabeth Morgan in 1829, and the couple had fourteen offspring. Perhaps to lessen the financial strain on his parents, their third son, James George, went to sea in 1849 at the age of seventeen. He was Sunday’s grandfather.

James’s seafaring career brought him out to Australia on the barque Priscilla in January 1853. While in quarantine at Portsea, James and crewmate Jeremiah Twomey attempted to desert ship, but were caught and brought back. Their actions were prompted—according to family legend—by the behaviour of the captain, who was fond of drink and used to ‘knock them about’.11 James escaped the Priscilla on his second attempt, climbing down the anchor chain then swimming and staying afloat until he reached the beach on the Queenscliff side, a considerable feat of endurance. A picturesque version of events told by a local fisherman saw James avoid detection by hiding in a cave inhabited by the former convict William Buckley, who was famous for spending thirty-two years with the Watourong people after absconding from his ship in 1803.

Unlike many deserters James was not tempted by gold fever. Instead he took advantage of the vacancies made available by the sailors-turned-prospectors, finding employment as an oarsman on the hospital ship Lysander. Thus he settled in Queenscliff, a wise decision given the hard-luck stories coming out of overcrowded Melbourne. Later that year he met Emma Lawrence Pow—a ‘strong, healthy and most lovely’ lass who arrived from Liverpool with 370 women on the Australia on 17 September 1853.12 The ship was full of beautiful girls and the men at Queenscliff were wildly excited by its arrival. Emma came from meagre beginnings in Dorset, England, and after the death of her father her impoverished mother decided to send her young daughter to the colonies, where employment and better prospects were virtually guaranteed.

Although Emma’s age was recorded as nineteen on the Australia’s passenger list, she was in fact only fifteen. When she and James married two months later, on 3 November 1853, at St James’ Cathedral, Melbourne, they gave their ages as twenty-two and twenty-one to circumvent the necessity of parental consent. They lived for the first year of their marriage in a tent on Queenscliff’s eastern beach, then in a small cottage that would be their home for the next twenty-six years. James eventually became the assistant lighthouse keeper at Point Lonsdale. He and Emma had sixteen children, of whom thirteen survived into adulthood—ten boys and three girls. Among the boys were William Lawrence, known as ‘WL’, a business genius and the next patriarch of the family, and the much younger Arthur, Sunday’s father, born in 1872.

James Baillieu c.1885

Emma Baillieu c.1900

James is remembered as an honest, good-natured and communityminded man who transcended class barriers to be elected to the Queenscliff borough council in 1884 before becoming mayor in 1892. He was an active Freemason, as were his sons, a point of consequence in terms of the professional network it opened for the family. Together James and Emma fostered high moral principles and strong loyalty and love in their close-knit family. Sunday would also hold love and fealty dear, applying these values beyond ...