![]() Part 1

Part 1![]()

CHAPTER 1

Uprootings: A History of Somalia

In 1994 Shirin Ramanzali Fazel reflected on the land of her birth and the history of the country that had led her to write her memoir, Far Away from Mogadishu:

Somalia. The Egyptians baptized you ‘Land of the Gods’, and the Queen of Sheba loved your incense and your myrrh. In 1333 Ibn Battuta, in his travels, described Mogadishu as a large city, rich with trade. There, fabrics were woven and then exported to Egypt and other countries.

Somalia, land of trade with India and with China. You had your courts, kings and queens. The nomads wandered inland, free men with proud faces behind their caravans of camels.

Somalia, land of poets. Sufis and Saints departed from your shores to spread the word of Allah, until Vasco de Gama destroyed every last one of your sultanates, burning all that he could not take away with him.

Somalia, land of conquest. From that time on, no more trade. Your terrorized people fled inland. The European colonizers came and raped the land, sowing the seed of future horrors. After independence, dictatorships—puppet governments that are convenient for the superpowers.

Somalia, my land. Now you have exploded; you could not go on any longer! You no longer respect anything: not tradition, religion, or tribes … Men no longer distinguish between brothers, sisters, children. With their kalashnikovs in hand they feel like gods. They rob, pillage, rape and kill. They impair their senses with drugs. You have neither mother nor father anymore. You have no compassion for anything. You destroy your people, the future and the past.1

Somalia has been devastated by years of intractable conflict: the capital city Mogadishu’s buildings were largely reduced to rubble by two decades of civil war; attempts at governance of the country have been, until very recently, ineffective. In order to understand the historical trajectories that inform the contours of possible spaces of belonging for Somalis who have fled the war and resettled in Italy and in Australia, this chapter draws on an existing body of scholarship to give an overview of Somali history, politics and society. After briefly outlining the nation’s pre-colonial history, it emphasises the context of Italian colonialism in the Horn of Africa, which significantly shaped Somali culture and society. The divisions resulting from the colonial administration of Somalia are considered by many scholars to have contributed to the country’s unrest.

This is a history that is crucial for understanding Somali imaginings of identity and belonging in the diaspora. In observations of Somalia, it is perhaps ironic that some scholars in their political and historical writings have proposed the country to be the perfect example of the nation state due to its perceived cultural and linguistic homogeneity. Somalia’s ‘pastoral democracy’, a term coined by Africanist scholar I.M. Lewis in the 1950s, has been idealised by scholars such as Ernest Gellner. Gellner considered the country as classically post-colonial insofar as it was forced to adopt a postcolonial perception of history at the time of its inception, when, under colonial influence, prefabricated notions of the past, institutional models and political systems were inherited. During General Siad Barre’s military rule in the 1980s, Gellner considered Somalia to be:

[O]ne of the examples of the blending of old tribalism based on social structure with the new, anonymous nationalism based on shared culture. The sense of lineage affiliation is strong and vigorous (notwithstanding the fact that it is officially reprobated, and its invocation actually proscribed), and it is indeed crucial for the understanding of internal politics.2

Yet there is no consensus on this notion of shared culture and history. Lewis, for instance, has emphasised instead the social divisions within Somali society due to tribal paradigms that tended towards anarchy and fragmentation rather than unity. Lewis writes that attempts:

to devalue and even extirpate these internal divisions, which always threatened national solidarity, assumed many forms, ranging from denial to political suppression. The most colourful, perhaps, were the public burials (and other measures) instituted by the dictator General [Siad] at the height of his powers and in his ‘Scientific Socialist’ phase.3

In turn US anthropologist Catherine Besteman has questioned Lewis’ assertion that such loyalties always threatened national solidarity, drawing on her 1987 fieldwork research in the Middle Jubba Valley:

A unitary focus on clan rivalry as the destructive force fuelling genocidal conflict and state disintegration in Somalia overlooks the many other aspects of Somali society, politics and history that informed people’s daily lives prior to 1991. It also fails to explain why clan tensions should suddenly erupt on so grand a scale and with such brutal devastation, apparently for the first time in history.4

What is clear is that each of the different historical perspectives instils its own set of problems, creating multiple visions of reality that advance different solutions to the country’s crises. Drawing on a body of historical literature on Somalia to help understand this complex situation, this chapter examines Somalia’s pre-colonial history and extends the analysis then to colonial conquest and administration. In addition, it takes into account the period of Independence from 1960 and the Socialist epoch that began with Barre’s coup in 1969. The chapter concludes by drawing together more recent perspectives that have emerged in the wake of civil war.

Pre-colonial History and the Partition of Africa

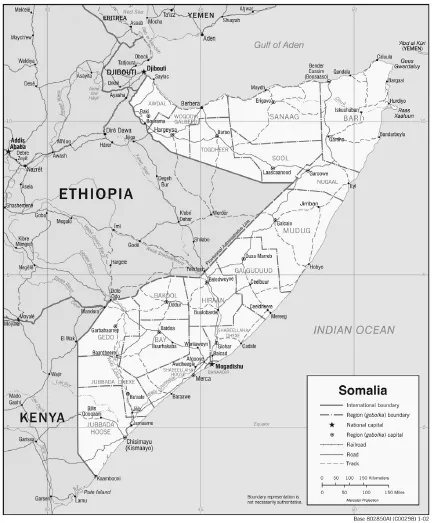

Situated in the north of East Africa within a region commonly called the Horn of Africa (see Figure 1.1), the pre-colonial history of the area now known as Somalia is multi-layered and, inevitably, contested. The name of the country is said to derive from the Somali Muslim Cushitic-speaking population who live within and beyond Somalia’s borders.5 While there are a variety of cultures within the Horn of Africa, certain characteristics, such as geography and religion, are common to the entire region. Islam and Coptic Christianity are the two most widely practised religions within the Horn. Ethiopia was a home to Christianity until the fifteenth century when Islam expanded into the region from the Eritrean coast. Somalia is still considered an Islamic country.

Located near the Arabian Peninsula, the Horn of Africa has, for centuries, been a landing place subject to colonisation by populations from the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden. Arab tribes are said to have descended on the Gulf of Aden coast in the seventh century, establishing the Sultanate of Adal.6 During the sixteenth century, the Sultanate of Adal disintegrated into small states. The Arab colonisers who had settled along the coastline in successive waves gradually migrated from the north to the south towards the centre of the Somalian peninsula, superimposing themselves on the native populations, such as the Bantu, now a minority in Somalia.7 Writing at the time of the Italian colonisation of Somalia, Tommaso Carletti saw the activities of these colonisers as ‘compact groups of Somalis’ migrating ‘from the dry, sandy and rocky terrain of the north towards the wetter regions touched by the Uebi Scebeli and Giuba [Jubba] rivers’. He believed these areas were likely to have appeared to the Arab colonisers as a kind of mirage or Promised Land.8

Figure 1.1: Map of Somalia

Source: African Studies Center, University of Pennsylvania

Somalis are believed to have populated the Horn of Africa around 1000 AD. The majority of Somalis were nomadic pastoralists who, as a result of geographic and climactic factors, embarked on a vast movement inland from the Gulf of Aden. Those who settled among the Bantu cultivators in the south adjusted to a more sedentary existence built around agricultural activities, whereas the majority of Somalis continued a mainly pastoral existence.9 Prior to colonisation, Somalia’s agricultural economies operated in autarky while the coastal centres of the north and south maintained commercial trade with the outside world. Without a fleet proper, these small centres of the country became landing docks for colonial and oriental empires rather than becoming actual commercial centres in their own right. Trade with the outside world was established through social networks and conducted in the currency of the visiting commercial partners or by bartering.

By the end of the eighteenth century, a Sultan from Muscat, Oman, who dominated Zanzibar island (off the Tanganyika coast), extended his authority and interests to several Benadir ports. (The noun ‘Benadir’ here denotes the entire southern Somalia.) At a time and place in which a sovereign or centralised statehood was unheard of, the Sultan’s administration of the ports of Benadir constituted the sole power beside that of the traditional authorities customarily and autonomously formed by each tribe. It was into this geopolitical climate that the European colonisers entered at the end of the nineteenth century.

Towards the end of the nineteenth century, France, Egypt and Britain successively occupied parts of the Somali coast. An Anglo-French agreement in 1888 would establish a border between different parts of the peninsula, later to be known as Djibouti and the British protectorate of Somaliland. During the 1880s, a recently unified Italy viewed Somalia as a potential bridge to access Ethiopia.10 ...