![]()

1

MONEY FOR NOTHING

Reputation, Trust and Ethics

Paul Kofman

Reputations, which are built over time, are a record of past performance, while trust is forward-looking. A bank’s track record in delivering good, fair and reliable service helps build customer trust in its future performance. Those customers will return, and the word will spread to prospective new customers, which will enhance the bank’s future prospects. A bad reputation, on the other hand, erodes trust. It makes customers think twice before entrusting a bank with their business. It reduces the likelihood of repeat business from customers who have experienced the reason for the bank’s poor reputation, and new customers may be even harder to attract.

Reputation can build or break trust, and trust is the key to a successful and sustainable banking business. There is a tacit understanding in the banking sector that a loss of reputation is tantamount to the end of a career in banking. In response to his dismissal for a breach of professional conduct, former Bank of America employee Thomas Chen stated: ‘We just need to re-establish our reputation because without that you can’t be an investment banker’.1

Individuals are likely to take pride in being part of a reputable industry. The loss of that reputation can hurt morale and may affect work cultures and individual behaviours. A bad reputation may even make an individual reluctant to disclose their work or employer in conversation with friends and strangers. A 2006 Australian television commercial made this point rather poignantly. When the host of a barbecue reveals that he is a banker, a sudden silence descends on the party and people look shocked. The palpable tension is only broken when the flustered host tells everyone which bank he works for. That bank’s reputation is apparently different from the ‘typical’ bank, so conversation resumes, and the guests smile and acknowledge the host as a ‘good guy’ working for a ‘good bank’.

By reinforcing the message that banks in general have a bad reputation, the bank in this television ad plays a dangerous game in portraying itself as the stand-out. In addition, this is unlikely to be of great benefit when conducting business through public trust. An individual’s reputation clearly needs to be supported and sustained by the sector’s reputation before that individual can expect public trust and trade on it. Of course, the sector consists of organisations as well as individuals. The organisation to which an individual belongs therefore also has a bearing on the public’s perception of trust. In judging a sector’s reputation, the public is likely to consider the average, or typical, behaviour of its representatives, be they organisations or individuals. Unfortunately, this provides an opportunity for less scrupulous individuals to benefit from the sector’s reputation and thereby discourage any investment in upholding or improving that reputation.

Safeguarding professional and industry reputations has always been challenging. To ensure that a sector’s standing didn’t sink to the lowest level among its representatives, medieval guilds—the predecessors of today’s accreditation bodies—were established to secure the long-term reputation of certain professions (craftsmen and merchants). The merchant associations’ motivations were undoubtedly protectionist by limiting and restricting professional access. Performing to exceedingly high standards became a prerequisite for aspirational apprentices to be considered for admission. And even after being admitted, a lapse in maintaining those standards could be sufficient grounds for the guild to levy fines, or even expel the miscreants. The guilds were clearly aware that a single individual’s misbehaviour could lastingly dent the whole profession’s reputation and thereby damage all members’ business interests.

Reputation had its own rewards for the guilds and its members—business profits, promotion, status and so on—but establishing a reputation and then jealously guarding it came at a price. The guilds imposed a significant professional entry cost through lengthy apprenticeships and excruciating professional examinations. Ultimately, the economic cost of the guilds’ protectionist nature, and nepotism in apprenticeships, led to their demise. Merchants opted out and, supported by innovation and economic growth, became capitalist entrepreneurs and created corporations. Apprenticeships disappeared, replaced by a labour force. The crafts could not compete and either disappeared or were absorbed into the new corporations. Responsibility for the maintenance of professional standards shifted from the individual to the institution. Entry to the profession was no longer strictly supervised, but rather was left to economic demand and competition between institutions.

The guilds’ demise had much to do with the advent of capitalism and free markets, including free access to professions. Of course, the guilds were mainly restricted to the ‘craft’ professions. There never was a guild for a finance profession. While the guilds have disappeared, various professional accreditation agencies (such as those for actuaries and accountants) nowadays act in similar ways and attract similar criticism for making access to the professions unnecessarily restrictive, thereby diminishing competition and driving up prices. Yet, their absence in other corporate sectors, like banking and financial advice, may well contribute to consistently low levels of reputation and public trust.

IN THE PUBLIC EYE

Polls and surveys seek public opinion about a range of aspects of our lives, including the reputations of various professions and service providers. The intent of such surveys is to provide insights for the industries in question, and at times they have resulted in enhanced consumer protection—they can tell consumers to be wary and alert when dealing with certain professions or service providers that have a bad reputation. Ideally, those poorly rated will take notice and set out to improve their reputations accordingly. But disappointingly, longitudinal trust surveys reveal that relative rankings are stable, if not entirely stagnant. For example, a 2006 report entitled Treating Customers Fairly, by British consumer analyst Mintel, found that financial institutions continue to be challenged by a lack of public trust.2

According to the Mintel report, when British consumers were asked which groups out of twenty types of professionals would treat them fairly, they rated finance professionals particularly poorly. Pension companies were perceived as behaving fairly by just 7 per cent of those surveyed. Investment managers came out even worse, receiving only 4 per cent approval. Financial advisers were rated slightly better, considered as trustworthy by 12 per cent of those surveyed, followed by insurance companies at 10 per cent. Accountants and lawyers also appeared low on the fairness league table. Doctors, on the other hand, emerged from the survey with a rating of highly trustworthy (in relative terms)—they were the only profession that managed to win the favour of over 50 per cent of consumers.

RANKING ON ETHICS AND HONESTY

Source: Based on survey data from Roy Morgan Research, ‘Roy Morgan Image of Professions Survey 2016: Nurses Still Easily Most Highly Regarded’, 11 May 2016, http://www.roymorgan.com/findings/6797-image-of-professions-2016-201605110031

Mintel’s analysis was published precisely one year before the onset of the 2007–08 global financial crisis. If investment managers had an image problem at the height of the bull market, then surely after the stock market collapsed in the next few years, their ranking would descend further, right? Pension funds, for example, were fully funded and generated very good returns in 2006. After some customers lost entitlements, faced increased premiums, and had to postpone retirement, one would have thought those pension funds might be adversely affected in the ranking table. Well, no. There was in fact very little evidence of such adjustments by the public. That observation suggests that the actual loss of money does not drive the public perception of banks. Banks’ reputations fare just as poorly in good times as in bad times.

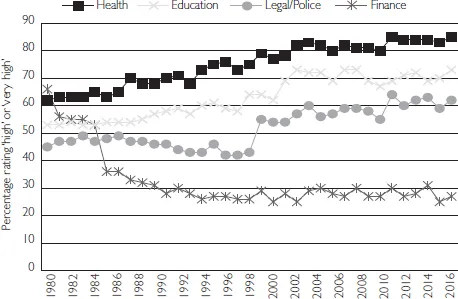

The above graph, drawn from the results of an annual survey conducted from 1980 until 2016, illustrates the evolution of public perception of the ethical and honesty standards of four broad professions in Australia. The survey results corroborate Mintel’s 2006 findings for Britain. The health profession is regarded as highly ethical and honest. Education comes a close second, followed by the legal/police area. Finance and business management, however, languish at the bottom, with only one in four surveyed subscribing to an ethical finance sector. It would be tempting to attribute some of the differences to the public preferencing public services as more trustworthy. But with increasing private provision of health (and education), that is not so clear.

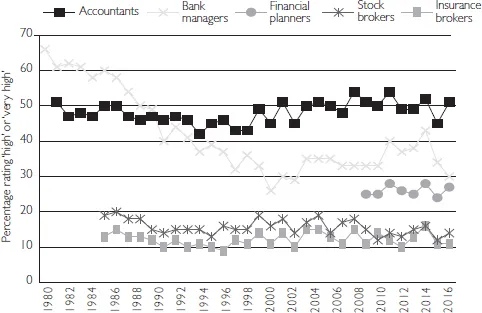

Another striking feature in the above figure is the stark decline of the finance sector in the first ten years (the 1980s) of the sample. To better understand this decline, it is instructive to consider the heterogeneity of the sector. The next figure illustrates the ethics/honesty rankings for five subgroups in the finance sector, again from 1980 until 2016. The public perception of accountants, insurance brokers and stock brokers has not changed markedly over this time. The perception of bankers, however, has dropped dramatically from almost 70 per cent to just over 30 per cent, crossing below the consistent ranking of accountants. One could conclude this may be related to Australia’s decade of financial deregulation.

An interesting feature of the graph is the very low ranking for brokers, around 15 per cent, which is significantly less than for financial planners. While both are segments where commissions have created significant potential for conflict of interest, financial planners seem to have benefited from a slightly better public perception. It is interesting to ponder how and why the public discriminate between these somewhat comparable occupations. A related factor may be that financial advice is provided in face-to-face customer relationships, whereas brokers’ services are sometimes provided in a manner considered less personal.

RANKING ETHICS AND HONESTY IN FINANCE OCCUPATIONS

Source: Based on survey data from Roy Morgan Research, ‘Roy Morgan Image of Professions Survey 2016: Nurses Still Easily Most Highly Regarded’, 11 May 2016, http://www.roymorgan.com/findings/6797-image-of-professions-2016-201605110031

The overriding feature of the Australian survey, and similar surveys in other countries with sophisticated financial institutions, is the consistently poor public perception of the finance sector. The Chicago Booth/Kellogg School Financial Trust Index provides a quarterly measure of the confidence Americans have in their financial institutions.3 It shows that Americans’ trust in banks is remarkably similar to Australians’ trust in bank managers—around 33 per cent. While such surveys do not normally extend beyond the past thirty years, a reading of the media commentary of the 1930s or even the 1880s suggests that this perception is not a modern phenomenon. What is interesting is that increased public access to information, improved transparency of activities, and almost real-time exposure of misbehaviour has apparently done very little to change the perception for the better.

A CAUSE FOR DISTRUST

To better understand why the public has persistently rated the finance sector poorly for honesty and integrity, it might be instructive to compare the core professional characteristics of the health and education sectors with those of finance and business. It is worth bearing in mind that the surveys reflect the public’s perception of, and their experience with, the finance sector. They do not necessarily provide an objective measure of ethical behaviour in finance. They are also limited to the public stakeholder. There are no similar surveys for the other stakeholders, like governments, regulators, corporations, other financial institutions, or even customers. It is therefore appropriate to start with the key characteristics that affect the profession’s interaction with the public, rather than its equally important interactions with corporations or with other financial institutions.

Four key factors can be identified that are influential in contributing to the public’s lack of trust in the ethics and integrity of the finance sector:

1. the complexity of the service

2. the information asymmetry between professionals and customers

3. the familiarity with the subject matter

4. the uncertainty of the outcome.

COMPLEXITY

Most people know little about the inner workings of the sectors which they engage for services, and therefore they may feel at a disadvantage when interacting. Some may even have a natural inclination to distrust the better-informed party. Such distrust may well be on the rise in an increasingly specialised environment where knowledge is ever so rapidly accumulated by experts—although access to information has certainly led to more-informed customers, if they are interested in doing their research.

In relation to the finance sector, there have been efforts to boost confidence to engage with it. Such efforts include financial literacy programs, informative websites (populated by regulators or an ombudsman), and educative information distributed by financial institutions. Imparting or sharing knowledge can enhance the relationship with the public. Attempting to restrict (and potentially abuse) knowledge, on the other hand, can further strain the relations between the sector and the public.

If the knowledge is considered too complicated or specialist to communicate, then a sector needs to convince the public it is using that knowledge for the benefit of both individuals and the public more generally. The health profession is the standard-bearer here, justifying its persistent high ranking on the ethics scale. But even that profession occasionally suffers from a lack of trust, particularly when it fails to communicate the ‘knowledge-for-good’ argument. Consider, for example, the debate around stem-cell research, where the health sector failed to clearly communicate the benefits of using human embryonic stem cells in research to cure disease and alleviate suffering.

So is the finance sector perceived in relation to the knowledge which it holds? The level of knowledge and professional competence required to be successful in finance has increased exponentially in the past few decades. Comprehensive financial deregulation resulted in new waves of financial innovation and financial engineering. Rather than always explaining the innovative new assets and investment products to their customers, some banks instead have used and protected their inside knowledge as a valuable competitive tool. In some cases, what may seem as ever more complicated products are created and marketed to what could be perceived as an ever more disadvantaged clientele—not just institutional investors but retail clients as well. A 2017 Consumer Federation of America survey reflected this erosion of public knowledge of pivotal financial information (credit scores).4

The introduction of a range of mortgage products—from no-deposit, interest-only loans with offset account to mortgage-backed securities (MBSs)—has been quite illustrative of the problem. Tempted by lower monthly repayments, home-loan borrowers have not always realised that interest-only loans carry significant risk of underwater mortgages in overinflated real estate markets. (A mortgage is defined as underwater when the balance of the mortgage exceeds the market value of the property.) Likewise, the highly inventive MBS market allowed banks to transfer significant risks of portfolios of non-performing home loans. Their complexity confused and in some cases blindsided investors, rating agencies, regulators, and in some instances the banks themselves. It would appear that some MBS originators were either unable to explain the true nature of the assets, or deliberately withheld that information from the investors.

The change from predominantly plain-vanilla mortgages to mortgages with complicated bells and whistles attached was acknowledged as a ...