eBook - ePub

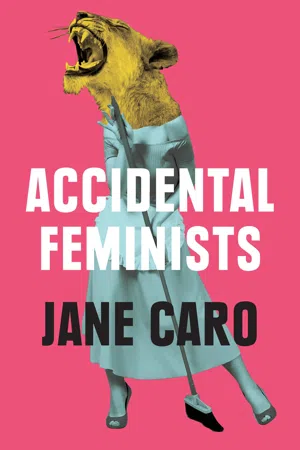

Accidental Feminists

About this book

Women over fifty-five are of the generation that changed everything. We didn't expect to. Or intend to. We weren't brought up much differently from the women who came before us, and we rarely identified as feminists, although almost all of us do now. Accidental Feminists is our story. It explores how the world we lived in—with the pill and a regular pay cheque—transformed us and how, almost in spite of ourselves, we revolutionised the world. It is a celebration of grit, adaptability, energy and persistence. It is also a plea for future generations to keep agitating for a better, fairer world.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

DAUGHTERS OF FEMINISM

Her name was Kerrie (we were all called Kerrie, Debbie, Jane, Lynne or Sue in those days). It was 1972 and we were fifteen and reaching the end of what was then called Fourth Form. They call it Year 10 now.

We were both students at a bog-standard, co-ed public high school in the boondocks of Sydney’s Northern Beaches. It wasn’t a posh school, and in those days it enrolled the children of the entire local community. My father was a company director. Maybe Kerrie’s dad was too, or perhaps he was a tradie or operated a small business. Back then, we didn’t know what our friends’ dads did and we didn’t care. Our mums generally didn’t do paid work, unless you were the unlucky offspring of the ostracised and whispered-about ‘deserted wife’. The term ‘single mother’ was not used because it was dads who took off, not mums. Mums couldn’t, no matter how miserable or mistreated they might be. They had little choice: not only did they rarely earn any money, but the social stigma attached to a woman who left her family (black eyes and bruises notwithstanding) was terrifying.

Kerrie was in tears. We were about to do our School Certificate, which was a much more significant exam then—when most students left school at 15 and it was their highest educational qualification—than it is now, but that wasn’t the problem. Kerrie was a bright girl. She’d worked her way up from the bottom classes in First Form (Year 7) to the top English class. She knew she was going to ace the exam. Kerrie was distraught because her father had just informed her that no matter how well she did in the School Certificate, she would not be going on to Fifth and Sixth Form. He could not afford to have both his kids out of the workforce for another few years, and as she was ‘just a girl’ she was the one who would have to leave and get herself a job. The injustice of this hit my friend hard. She knew she was a better student than her brother and that she enjoyed school while he hated it. She had ambitions to go to university; he’d rather poke his eyes out with a fork. But he was a boy and she was a girl, and that was that.

I was outraged on her behalf. My mother was a feminist, a member of the Women’s Electoral Lobby, and hardly a day went by without her fulminating about the injustices visited upon women because of their gender. But I was the child of a well-to-do family. No tough decisions had to be made about whether we could afford to let me stay on at school or go to university. I comforted Kerrie as best I could and urged her to fight her MCP (male chauvinist pig, as they were called in 1972) of a father. All to no avail, of course. Kerrie left at the end of that year and disappeared into the ranks of the shop assistants, filing clerks, receptionists and apprentice hairdressers that swallowed more than half of the girls I’d shared classes with.

Looking back on it, for both the girls and the boys who stayed on for their last two years of secondary education, entering the senior school was a class marker. Our fathers tended to have white-collar jobs and wanted us to have them too, even if we were girls and only expected to work for a few years until we had kids.

When Amanda, a student at a Catholic high school in the 1970s, thought about her future—something she did very rarely—she says that she ‘hoped to find a spunk to link up with, and didn’t think too much about what happened after’. A ‘spunk’, as I recall with great fondness, is what teenage girls called attractive teenage boys back then. Debbie imagined ‘living a comfortable life’. She says, ‘I dreamed of owning an apartment near the ocean somewhere. I imagined that my hard work would pay off.’ Theresa did well at school and expected to go to university. She says, ‘I expected (hoped) I would marry and have a family one day. I don’t think I really ever thought beyond that.’ Susan’s adoptive father was abusive and frightening, so she barricaded herself into her room and lost herself in sci-fi and horror novels. She also became obsessed with her horse. Nevertheless, she describes herself as a teenage girl who lived ‘just one day to the next. Most of it is simply a grey fog.’

The Australia of the 1960s and 1970s, the era when I grew up and when most of the women now over fifty did as well, was a different world from today. I suspect that, apart from the labour-saving devices and shorter skirts, men and women from the 1860s and 1870s would not have found much that surprised them a century on. The traditional family was still just that for most people. Us kids called our friends’ parents Mr and Mrs, and never used their first names in the way children routinely do now. We were all terrified of fathers as a species and avoided having anything whatsoever to do with them. This was the era of ‘spare the rod and spoil the child’, and fathers were often the disciplinarians. My friends would casually talk about ‘getting a belting’ from their dad, a punishment that sometimes involved their dad’s actual belt. Susan’s adoptive father invented horrific punishments for his two daughters, including being forced to walk around the house naked or in their underwear. When as a small child Susan confided in her teachers about her home life, she was taken out of primary school, her family moved house and everyone was told she ‘was a liar who would make things up’. In those days, no-one in authority ever followed up and families were often allowed to just disappear.

Fortunately, for most of the rest of us, avoiding fathers was not difficult as they were rarely home, even on weekends. My own rather unconventional father (I was certainly not afraid of him, and he never hit us) worked all week and then played cricket for most of the weekend. My mother resented this mightily and—as women’s lib began to make headlines—her discontent was increasingly verbalised. But, and I can’t emphasise this strongly enough, she was very unusual.

When the current generation look back at the world of my childhood and adolescence, the world I shared with the cohort who are the focus of this book, they see the rising tides of revolutionary social movements—the anti-war demonstrations, the fight against apartheid, the rise of black power, social justice movements of all kinds, the youth-quake in general, and, of course, the rise of women’s liberation. These are the things that stand out, particularly in hindsight. They were also the focus of our nightly TV news—in flickering black and white until 1975. However, they hardly affected most of us at the time. We did what people do as the great tides of history break around them: we jogged along with our lives just as we had always done.

Most of my girlfriends were not ambitious. They did not expect to have careers. I know this because I argued with them about it as we did the drawback on our Marlboro ciggies, hiding from our teachers round the back of the senior studies block. My girlfriends knew what their future looked like. It looked like their mothers’ had, back in the 1940s and 1950s. They would work for a few years, have some fun, meet a guy (a spunk), marry, save for a deposit on a house or a block of land, and then they’d have kids. Even the girls who wanted to go to uni were all hoping to get teacher scholarships. It was the only job we could think of that worked around having children. Leanne considered being a teacher but decided that ‘because it was a typical job that women did, I didn’t want to do it’. I had a similar thought and did a straight arts degree at uni. But Leanne and I were the exceptions. Most of the girls I went to school with were not feminists. Indeed, the ‘women’s libbers’ we saw on the news irritated them. Their demands and arguments made my friends uncomfortable, perhaps because they drew attention to things they did not want to think about. Many of my schoolfriends’ mothers fed their daughters’ dislike. They saw the slogans, the demos and the demands of feminists as a criticism of their lives as homemakers. They reacted defensively and often actively discouraged their daughters from having any ideas above their allotted female station.

This attitude persists. Only a couple of years ago, I remember a female school principal (she was well into her forties) telling me with tears in her eyes that when she told her mother she had been elected president of the area’s Primary Principals’ Association, her mother rolled her eyes and asked her what made her think she could manage a job like that. The lack of confidence our mothers often had in their own ability to navigate the world is the poisoned chalice they bequeathed to their daughters.

It is hardly surprising that the women of the 1950s and 1960s had this profound distrust of their own abilities. Women were routinely infantilised and patronised. Briefly allowed a modicum of agency and value when their labour was required during World War II, efforts were redoubled in the immediate postwar decades to remind women of their inferiority and their ‘natural place’ in the home. Indeed, as civil rights for other groups in the community gathered momentum, particularly in the US, women’s rights, if they were included at all, were literally included as a joke. On 8 February 1964 (what a seminal year it was) an elderly congressman, Howard Smith, who favoured segregation, added an amendment to President Johnson’s 1964 Civil Rights Act. He proposed adding the word ‘sex’ after race, colour, religion and national origin.

According to author Gillian Thomas, Congressman Smith ‘played his amendment for laughs’, cracking sexist jokes that are hair-raising in retrospect but were quite unexceptional at the time, and his suggestion was greeted with obliging guffaws by the male-dominated Congress. Some of the twelve (out of 435) women members rose to try and combat the laughter and make some serious arguments in support of the amendment that would make discrimination against women illegal. Thomas quotes Democratic congresswoman Martha Griffiths as saying to the House: ‘I presume that if there had been any necessity to point out that women were a second-class sex the laughter would have proved it.’ Despite the laughter, both the amendment (an attempt, according to Thomas, by segregationists to derail the Civil Rights Act) and the bill were passed.

Australia was certainly not immune to this routine disrespect towards women and their work, their rights and their achievements. In 2003, the ABC ran series two of A Big Country Revisited. The program compared the Australia portrayed in the original documentary series (1968–91) with the Australia of the twenty-first century. I remembered A Big Country well from my youth and enjoyed its resurrection. The episode that etched itself into my consciousness was called ‘Grey Hair Doesn’t Mean You’re a Fuddy Duddy’, and looked at the Country Women’s Association then and now.

What struck me was the extraordinary tone taken by the male narrator of the original program from the 1960s. He spoke of these women with the same patronising derision that the US Congress had indulged in a few years earlier. No matter how hard these women worked or how much money they raised, the narrator saw them as a joke. They were spoken of as if they were children who were aping the grown-ups (aka men). What they did might be cute, but it was also futile—an attitude that goes right back to Samuel Johnson (1709–84) and his much-quoted response to attending a Quaker meeting: ‘Sir, a woman’s preaching is like a dog’s walking on his hind legs. It is not done well; but you are surprised to find it done at all.’ This attitude of condescending astonishment towards any achievement by a woman had survived virtually unchanged for over 300 years, well into the 1960s.

For the women of my generation (and no doubt for every previous generation throughout history), this derision mattered. The almost universal scorn and ridicule towards women very effectively undermined their confidence and self-worth. Susan’s adoptive father routinely referred to his cowed and submissive wife as ‘my little turd’. You can perhaps imagine the effect that had on his growing daughters. Social researcher Hugh Mackay in his book What Makes Us Tick? lists the ten desires that need to be met before you can live a satisfying life. He says he lists them in no particular order except for the first one, which is the most important. He calls it ‘the desire to be taken seriously’. When I first read Mackay’s book it was as if a light had been turned on. I saw clearly that feminism is the struggle by half the human race to be taken seriously by the other half. ‘Indelible in the hippocampus is the laughter’ said Christine Blasey Ford as she testified about her alleged abuse at the hands of Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh at his confirmation hearing. A phrase that resonated with women all over the world. When I was young, when the women of my generation were in their formative years, we were not taken seriously either. Nor, just as damagingly, were our mothers, or our grandmothers. Indeed, when I asked a number of women of my generation to answer some questions about their youth, aspirations, relationships and lives, not one of them said she wanted to be like her mother. Bev was unequivocal: ‘Trying not to be like my mother has driven me in untold ways throughout my life.’ Veronica agreed: ‘Anyone but her’ was her heartfelt response.

Feminism has had a considerable impact in the decades since my generation were quietly rejecting the lives their mothers lived, but the damage that had been done to the women who came before us was hard to shake off. As I half-joke on occasion, 2000 years of people being disappointed when you were born is not overcome in a few decades—and, make no mistake, when I was born, the birth of a boy was still cause for more celebration than the birth of a girl.

The major effect I can remember feminism having on my peers in the Frenchs Forest and Belrose of the 1970s was in terms of sexual liberation. We were all on the pill by the time we were sixteen, and most of us were having sex. My teenage years were also awash with illegal drugs, particularly marijuana and, for the really daring, LSD. Oddly, I was radical politically, especially about the position of women, but I was very square about drugs. Most of my friends were the exact opposite.

I am not arguing, however, that second-wave feminism had no effect other than sexual liberation on the women I knew. It revolutionised my mother’s life, giving her the courage to do a mature-age matriculation course at tech (as TAFE was then called) and go on to take advantage of Gough Whitlam’s education reforms. When the new Australian Labor Party (ALP) government abolished university tuition fees in 1974, a wave of mature-age women like my mother grasped their second chance with both, highly motivated hands. They could finally get the university education that their fathers (poor Kerrie) had denied them. Peta missed out on a free university education, but nevertheless went to Wollongong University and studied social science. She says graduating in 1994 boosted her confidence to such an extent that for the first time in her life she felt ‘I can do anything, or at least try’. Many other women who had been trained from birth to think poorly of themselves and their capacity had the same epiphany as they found, to their astonishment, that they had gained high marks on the university essays they’d handed in, despite their sense of inadequacy. Their confidence and self-esteem blossomed thanks to their unexpected success.

Women’s liberation had a huge effect on our teachers, too. We still had to put up with humiliating policing of our uniforms—particularly skirt lengths—but we knew enough to protest and we also knew many of our teachers fully supported our objections. That was liberating. Whether we were up for competing with blokes in the workplace or not, schoolgirls in the late 1960s and early 1970s were no longer as compliant and well behaved as those who had gone before us. This was shocking and unsettling, particularly to older generations.

Even so, the consequences for girls who rebelled when I was a teenager could be very daunting. I remember friends of mine being threatened by teachers, parents and religious leaders with the possibility they would be charged (yes, charged) with being ‘in moral danger’ and sent to what was ominously referred to as ‘The Girls’ Home’. Decades later, when I read some of the revelations about Jimmy Savile’s predatory paedophilia, particularly at a school for what was referred to as ‘emotionally disturbed girls’ (aka mouthy and defiant girls), my blood ran cold. In Ireland, of course, they ran the risk of being sent to the infamous Magdalene Laundries. And, no doubt, some of my peers were whisked off to Homes for Unmarried Mothers to await the birth of illegitimate babies that they were then not permitted to keep. The treatment of Indigenous girls was even more terrifying and horrific. In every case, it was the girls who were seen as bad and deserving of punishment, never those who preyed upon them—a routine cruelty that was accepted almost without comment in my youth, except, to their credit, by feminists. And, worse, the stigma attached to ‘wayward’ (or ‘emotionally disturbed’) girls made them sitting ducks for predators in ways that are only just coming to light now. Many of the women I interviewed hinted at abuse when they were young. Susan became pregnant at sixteen and was coerced into giving up her baby. As an adopted child herself, she says her situation was presented to her ‘as if it ran in the family’.

As always, vulnerability increased the lower the rung of the social ladder you occupied—but none of us were immune. Going to university might have been a marker of social class at Forest High in the 1970s, but sexism was having the same effects in posher schools and suburbs too. One of the most famous Sydney private girls’ schools (then and now) was Abbotsleigh in Wahroonga. Through the sister of a boyfriend, I had become friendly with a group of girls from that famous school, run, at the time, by the legendary Betty Archdale. While the private-school girls I knew tended to be called Sally, Fiona, Pippi and Deirdre rather than Kerrie, Karen or Lynne, they were no more unconventional than we were. They may have expected to marry a professional man rather than a tradie, but otherwise their life plans were much the same: a job (dental nurse, interior decorator, sales assistant in a posh shop), marriage and then children. No matter your social class, a man was still the only financial plan most girls could imagine. After all, it was the only model we had actually seen. The feminists might have talked a good game, but in the early 1970s that was largely what rhetoric about women’s rights seemed to be: argument and polemic.

The wave of discontent and rebellion that gave rise to second-wave feminism when I was young took everyone by surprise. No-one anticipated the changes in women’s lives that were to come. My favourite illustration of how blind the world was to the coming revolution is the famous Up series of films by Michael Apted. Beginning in 1964 (there’s that year again), the series continues today. A now-elderly Apted has been visiting the same fourteen Britons every seven years, starting when they were seven-year-olds. They are now sixty-one. The first episode was made for the British TV series World in Action.

The concept behind the series was the famous Jesuit motto ‘Give me a child until he is seven and I will show you the man’. The producers thought they were creating an exposé on the effects of social class—which they certainly did—but the series also turned out to be an essay on the revolution in the lives of women that has occurred in the last half-century. It is a revolution that in 1964 was unimaginable—so unimaginable that the fourteen seven-year-olds chosen by the producers for the original episode included ten boys but only four girls.Yes, four girls: one from an upper-class background, and three working-class friends. It is impossible that such a project today would be similarly cast. Indeed, even if it was tried, the outcry would be deafening. In 1964, nobody so much as noticed.

So why did the producers choose only four girls? Well, no-one thought girls’ lives would be very interesting, not even the girls themselves. They, like my friends a few short years later, assumed girls would just grow up, work for a bit, marry and have kids. Their lives would be shaped by their husbands’ lives, as women’s had been for millennia.

For many of the women who are over fifty in the early twenty-first century, this is another of the assumptions that formed them. Even if you had a feminist mother like mine, you still absorbed the messages about our limited future through the pores of your skin. As Australia’s former sex discrimination commissioner Liz Broderick brilliantly put it, sexism is like asbestos in the walls: you just breathe it in. We were baby-making machines, always had been, always would be, and we were supposed to be satisfied with that. The women who were beginning to assert...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction

- 1. Daughters of Feminism

- 2. Hags, Crones, Witches and Mothers-in-law

- 3. Dutiful Daughters, Wives, Mothers and Grandmothers

- 4. Gold-diggers, Beggars and Thieves

- 5. Women’s Work

- 6. Slags, Sluts, Gossips and Staceys

- 7. Invalids, Liars, Hysterics and Madwomen

- 8. Vessels of Repulsion

- 9. Loss and Lamentation

- 10. Past Our Use-by Date

- 11. Invisibility v. Independence

- 12. Rebels, Resistance Fighters and Role Models

- 13. Strategists, Policy Makers and Problem Solvers

- Acknowledgements

- Notes

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Accidental Feminists by Jane Caro in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Feminist Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.