![]()

Part I

ENEMY COMBATANT

![]()

1

A FORK IN THE ROAD

The Secret Service agents burst into the Vice President’s White House office without knocking.1 ‘Sir, we have to leave immediately,’ one of them announced brusquely, as they virtually hoisted Dick Cheney into the air and bustled him from the room. The forty-sixth Vice President of the USA is a heavyset man, but the agents moved so quickly that his feet barely touched the ground. They raced through the hallway, down a flight of stairs, through some doors and then finally underground into an emergency bunker beneath the White House. As Cheney caught his breath, the agents strode to doors at either end of the vault and sealed them shut. The Vice President was secure in the Presidential Emergency Operations Center (or PEOC). It was September 11, 2001.

US President George W Bush was away in Florida, where he was promoting his education policy. Dick Cheney was the most senior official in Washington DC, and only minutes earlier had been checking some speeches at his desk when his secretary interrupted to tell him a plane had flown into the World Trade Center. Cheney switched on the television and watched as the second jet slammed into the South Tower. Now the Secret Service agents informed him that American Airlines Flight 77 seemed to be headed for the White House. President Bush had been briefed on the New York crisis and was in a motorcade on the way to his plane, Air Force One, so he could return to Washington. Cheney snatched the receiver from a secure phone and called him. ‘Delay your return,’ the Vice President advised urgently. ‘We don’t know what’s going on here, but it looks like we’ve been targeted.’

At 9.39 a.m., Flight 77 smashed into the Pentagon. Cheney and the staff in the White House were safe, but their colleagues fifteen minutes away on the other side of the Potomac River were not. And neither was the USA. Five minutes later, the phone buzzed and Cheney picked it up. Bush was at the end of the line. His voice was grim. ‘We are at war,’ the President declared.

Bush spent most of the day onboard Air Force One or at military bases in Louisiana and Nebraska. The Secret Service feared the White House was still a target and wanted to keep Bush away. The President finally arrived back at the Oval Office around 7 p.m., and in an address to the nation an hour and a half later, he used the word ‘war’ again. At the time, it might have sounded like a rhetorical flourish in response to the urgency of the moment, but his use of the word ‘war’ established the mission that would define two terms of his administration. ‘America and our friends and allies join with all those who want peace and security in the world, and we stand together to win the war against terrorism,’ he vowed.2

That same morning, Australian Prime Minister John Howard was a few blocks away from the White House at the plush Willard Intercontinental Hotel.3 He had met George W Bush for the first time the previous day. With the Prime Minister were senior officials, including the head of his own department, Max Moore-Wilton, and the Secretary of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Ashton Calvert. The Australian Ambassador to Washington, Michael Thawley, had also asked prominent Australian business leaders, including the chief executive officer of Western Mining, Hugh Morgan, and the head of Chevron, David O’Reilly. Australia was lobbying the USA for a free trade agreement, and the group was due to head to the US Chamber of Commerce after the Prime Minister’s scheduled media conference at 9.30 a.m.

Howard had just seen television images of the first two planes ploughing into the World Trade Center when he started his remarks. Nobody was quite sure what was happening yet, so the press conference largely stuck to the news of the day back home in Australia. But as Howard spoke, the third plane slammed into the Pentagon. A Nine Network cameraman whispered the development to the Prime Minister’s press secretary, who signalled from the back of the room that Howard needed to finish. The Prime Minister hurriedly left and was told about the Pentagon. He took the lift up to his hotel room and drew back the curtains from his window. A thick plume of black smoke was rising into the air across the Potomac River. Washington was under attack.

The Secret Service agents with Howard ordered him to step back from the window. A fourth plane was pronounced missing too—it would eventually crash in Pennsylvania—and the agents feared that another strike on Washington was imminent. They quickly ushered Howard’s party out the back entrance of the Willard Hotel and into waiting cars. They sped down 14th Street to what they hoped was the safety of the Australian Embassy.

When they arrived, Thawley ordered everyone into the basement. The businesspeople went into one room and the journalists another. The Prime Minister was shown to a dusty area where the embassy’s maintenance staff normally worked. There was a cracked vinyl couch, a broken television set in the corner and a lot of mess—quite different from the sort of work space Howard was used to. Luckily, there was a phone. The Prime Minister immediately called Australia to speak to the Minister for Foreign Affairs, Alexander Downer, and the head of the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO), Dennis Richardson. He asked for a briefing, agreed to extra security measures for US and Israeli diplomatic posts in Australia and considered his next step.

A few hours later, the Prime Minister made his first detailed remarks about the attacks to the media, and while he did not use the word ‘war’, clearly it was on his mind:

It’s a day that recalls the words used by President Roosevelt in 1941—it’s a day of infamy that an attack of this kind can be made in such an indiscriminate fashion—not upon military assets as was the case in Pearl Harbour but upon innocent civilians: men, women and children going about their daily lives.4

That night, Thawley asked as many of the official party as possible to stay at his residence, including the Prime Minister. The group shared dinner, still stunned by the day’s events. The conversation revolved around what the terrorist attacks would mean for the world and how the USA would retaliate. People assumed a military response was inevitable to an attack of such an unprecedented scale.

Like Bush, the Prime Minister from the beginning assumed that September 11 was an act of war, not a mere crime. On 12 September, the US government provided Air Force Two to evacuate Howard and his party to Hawaii, where they then boarded a Qantas jet to Australia. On his way home, Howard spoke to Downer and Thawley. The Prime Minister wanted to invoke ANZUS for the first time in its history. ANZUS is a 1951 military treaty that binds the USA and Australia (and separately Australia and New Zealand) to go to each other’s aid in the event of an attack. The three allies signed the document after their close cooperation during World War II. On 13 September, the National Security Committee of the Cabinet met in Canberra in the Prime Minister’s absence. All agreed with Howard, and ANZUS was formally activated a day later.5 If the USA was at war, then Australia was too.

* * *

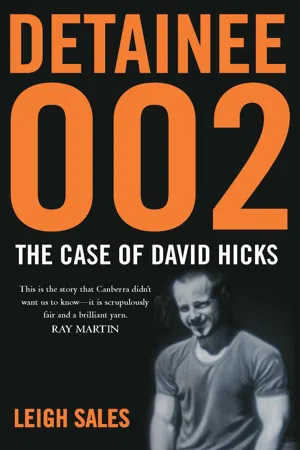

It is a long way from the Oval Office in 2001 to David Hicks’s spartan cell at Guantanamo Bay in 2007. But Bush’s view that the events of September 11 put the USA at war was, along with Howard’s agreement with this position, central to Hicks’s case. The Hicks matter can only be understood by starting at the beginning. Every question about why he was at Guantanamo Bay for more than five years without a trial, and what his imprisonment achieved, flows from there. Hicks was a captive in the War on Terror, a war without a clear definition or an obvious conclusion. This war is meant to make the world safer from terrorism and deliver swift justice to accused terrorists. The broad effectiveness of the mission is beyond the scope of this book. My central question is whether the handling of Hicks furthered the goals of the War on Terror while, at the same time, preserving the legal and human rights that distinguish democratic societies.

More than five years after his arrest, the basic facts of Hicks’s case are well known. The youth from Adelaide went overseas in search of adventure and ended up embracing Islamic extremism, the Taliban and al Qaeda. He was in Pakistan on September 11 and chose to return to Afghanistan. The Northern Alliance arrested him in December 2001 and handed him to the US military, which sent him to Guantanamo Bay. The Australian government said he could not be charged with anything under domestic law and left it to the Bush administration to deal with him. The Americans devised controversial military commissions to try Hicks and the other Guantanamo detainees. Lawyers, soldiers, diplomats and even the USA’s most important ally, the United Kingdom, decried the commissions as unjust. Eventually, even the US Supreme Court ruled them unconstitutional. But the Bush administration rewrote the rules and secured congressional backing. Australia stood by the process until the day Hicks pleaded guilty.

Critics of Bush’s war tactics, including human rights activists, civil libertarians and left-wing opponents, claim that Guantanamo Bay is the Gulag of our time, established by an evil cabal of ultra-conservatives within the Bush administration who made a calculated decision to use September 11 to expand presidential power. According to their interpretation, Howard sacrificed Hicks to this agenda because the Prime Minister does the USA’s bidding. All Australian government ministers and bureaucrats were complicit and refrained from any attempts to ensure that Hicks received a fair trial or decent treatment, lest they offend the USA. To these critics, Hicks was merely a naive adventurer who found himself in the wrong place at the wrong time. They claim he was tortured in US custody and argue that he should have been released years ago. The only heroes in this version of the story are the American military defence lawyer, Major Michael Mori, who fought for Hicks’s rights, and his father, Terry Hicks, who stood by him despite everything.

Hardliners in the Bush administration and the Howard government, along with conservative commentators, promote an alternate view. They hold that David Hicks was a serious threat who had to be held at Guantanamo indefinitely because there was no alternative. The delay in his case was the fault of his defence lawyers, who insisted on challenging the legality of the system. Hicks was an enemy combatant in a war with no geographic bounds. They argue that this is a different kind of war because the enemy—terrorists—do not fight by accepted rules; they target civilians and wage their campaign covertly. Therefore, Bush needs unprecedented powers to deal with them however he sees fit, including the power to rewrite the definition of torture in order to obtain intelligence that could save lives. Terrorists such as Hicks cannot be tried in regular courts because the rules of evidence are so strict that they might avoid conviction. Instead, they must face military commissions in which the USA writes the rules, sits in judgement and passes sentence. Attempts to rein in the President’s authority would threaten the USA’s national security. Anybody who does not accept this unquestioningly does not understand the danger posed by Islamic extremism.

The reality is far more complicated and nuanced than either of these conventional positions, which tend to reduce the issues to political point-scoring. The line between good and bad is blurred, and who is right and who is wrong remains unclear. In the words of a senior Australian government official:

Both sides seek to present the other as a caricature. Those who support the administration are fond of characterising the other side as soft on terror, unpatriotic, lacking understanding of the new threat. Those on the other side portray the Bush administration as trammelling all over the law, not caring about human rights. Hicks and Guantanamo are issues around which decent, rational people can disagree. But neither side will accept that the other opinion is decent or rational.6

Hicks’s case remains emblematic of some of the greatest challenges currently facing the world: the rise of Islamic extremism, how it motivates terrorism, the increasing power of non-state actors and how to deal with them. What are the rules in this War on Terror, and how do societies hold their governments accountable? As a nation, what rights and values—if any—is Australia prepared to trade in its fight against Islamic extremism? Is a facility such as Guantanamo Bay necessary or not?

Guantanamo has become a political lightning rod for Bush, as Hicks became for Howard. In the face of almost universal condemnation, both these leaders and their backers have frequently refused to acknowledge that the plight of the prisoners incarcerated in Cuba indefinitely is a serious concern. The Bush administration continues to ask the world to accept and trust that Guantanamo Bay and the controversial military commissions are necessary, even though the President’s credibility has been shattered by the failure to uncover weapons of mass destruction in Iraq, by the exposure of secret Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) prisons, by the administration’s approval of extreme interrogation methods, by the shocking mess in post-war Iraq and by revelations that many of the Guantanamo detainees, including Hicks, were not the ‘worst of the worst’ after all. Only in early 2007, after a public outcry on the fifth anniversary of Hicks’s imprisonment at Guantanamo Bay, did the Australian government begin strongly criticising the delay in the Hicks case.

Bush and Howard were not the only parties to the Hicks issue. Mori, the detainee’s military lawyer, became a cult hero in Australia as a result of his strong, public advocacy for Hicks. But did Mori and his civilian offsiders always act in their client’s best interests? There is no suggestion that Mori was anything other than a sincere and energetic counsel, but that does not put his defence strategy beyond critique. He was in an excellent position to strike a plea bargain on his client’s behalf three years ago, a course he finally took in March 2007. Hicks could have been back in Australia years ago, instead of sitting in Guantanamo Bay for several years while Mori waged an unsuccessful pressure campaign to force the Howard government to repatriate his client.

Similarly, did the activists and lawyers who fought the Bush administration all the way on this issue really care about Hicks as an individual? There was a steady stream of information about the parlous state of Hicks’s mental and emotional health as he spent year after year at Guantanamo Bay. Undoubtedly, Howard could have brought that detention and suffering to an end. But so could have Howard’s opponents, if they had chosen to stop challenging the system. Instead, Hicks became collateral in a bitterly fought culture war. The Howard government was constantly questioned about whether it viewed Hicks as a human being or a political pawn; it is only fair to ask the other side the same question.

Hicks is not a sympathetic character, but even after his guilty plea, there is unease at the lack of due process. Australians have an innate sense of a ‘fair go’. Our society is defined by the notion that all individuals, whether they are accused murderers or petty shoplifters, are entitled to a day in court to answer the charges against them. After more than five years in custody at Guantanamo Bay, there is doubt about whether Hicks had that opportunity or whether he pleaded guilty just to bring his ordeal to an end. Unlike a regular criminal, Hicks was not afforded standard legal process, simply because he was an enemy combatant in the War on Terror. The Bush administration promised the Australian government that if it trusted this experimental system, which set aside tradition...