- 160 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Conflict and Change in Cambodia

About this book

In the thirty years after the Second World War, Cambodia witnessed the reassertion of colonial power, the spread of nationalism, the birth and growth of a communist party, the achievement of independence, the stifling reform during the decade of peace, the rise of an armed domestic insurgency, the encroachment of an international war, massive bombardment and civilian casualties, pogroms and ethnic 'cleansing' of religious minorities. From 1975 to 1979, genocide took another 1.7 million lives. Then, after liberation from the Khmer Rouge regime, Cambodia survived a decade of foreign occupation, international isolation, and guerrilla terror and harassment. UN intervention and democratic transition were followed by Cambodia's defeat of the Khmer Rouge in 1999 amid continuing internal tension and political confrontation.

Against this backdrop of more than thirty years of conflict in Cambodia, Conflict and Change in Cambodia brings together primary documents and secondary analyses that offer fresh and informed insights into Cambodia's political and environmental history.

This book was previously published as a special issue of Critical Asian Studies.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

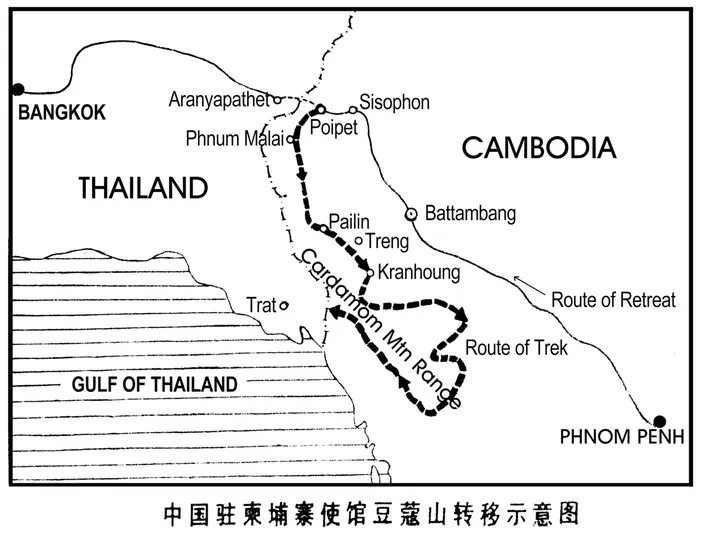

1. The Collapse of the Pol Pot Regime, January-April 1979

An Account of Chinese Diplomats Accompanying the Government of Democratic Kampuchea’s Move to the Cardamom Mountains*

The First Evacuation from Phnom Penh

The Second Evacuation from Phnom Penh

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Introduction: Conflict in Cambodia, 1945-2006

- 1. The Collapse of the Pol Pot Regime, January-April 1979

- 2. Democratization, Elite Transition, and Violence in Cambodia, 1991-1999

- 3. International Intervention and the People's Will: The Demoralization of Democracy in Cambodia

- 4. Logging in Muddy Waters: The Politics of Forest Exploitation in Cambodia

- 5. Contested Forests: An Analysis of the Highlander Response to Logging, Ratanakiri Province, Northeast Cambodia

- DOCUMENTS

- Contributors

- Index