eBook - ePub

The Ocean Sunfishes

Evolution, Biology and Conservation

- 300 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Ocean Sunfishes

Evolution, Biology and Conservation

About this book

The Ocean Sunfishes: Evolution, Biology and Conservation is the first book to gather into one comprehensive volume our fundamental knowledge of the world-record holding, charismatic ocean behemoths in the family Molidae. From evolution and phylogeny to biotoxins, biomechanics, parasites, husbandry and popular culture, it outlines recent and future research from leading sunfish experts worldwide This synthesis includes diet, foraging behavior, migration and fisheries bycatch and overhauls long-standing and outdated perceptions. This book provides the essential go-to resource for both lay and academic audiences alike and anyone interested in exploring one of the ocean's most elusive and captivating group of fishes.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Ocean Sunfishes by Tierney M. Thys, Graeme C. Hays, Jonathan D. R. Houghton, Tierney M. Thys,Graeme C. Hays,Jonathan D. R. Houghton in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Ecology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Evolution and Fossil Record of the Ocean Sunfishes

1 Dipartimento di Scienze della Terra, Università degli Studi di Torino, Via Valperga Caluso, 35 I-10125 Torino, Italy. Email: [email protected]

2 National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC 20560-0106, USA. Email: [email protected]

* Corresponding author: [email protected]

Introduction to Molidae

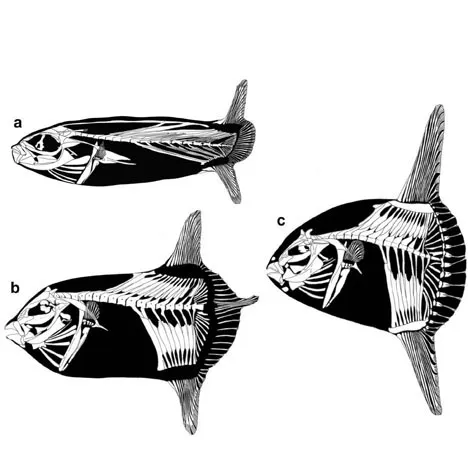

Molidae is a very small family of pelagic tetraodontiform fishes, commonly referred to as ocean sunfishes, which has five currently recognized species arranged in three genera, Masturus, Mola and Ranzania (e.g., Fraser-Brunner 1951, Tyler 1980, Santini and Tyler 2002, Nyegaard et al. 2018). Most of the molid species have global distributions in tropical to temperate seas (Fraser-Brunner 1951). For additional distribution information see Etsuro et al. 2020 [Chapter 2], Caldera et al. 2020 [Chapter 3] and Hays et al. 2020 [Chapter 15]. Species of the genera Masturus and Mola can reach gigantic sizes, growing to about 3 m in length and weighing more than 2,300 kg (e.g., Gudger 1928, 1937a, Santini and Tyler 2002, Forsgren et al. 2020 [Chapter 6]). Mola spp. are also considered one of the most fecund extant vertebrates, with individual females capable of producing up to tens of millions of eggs at one time (e.g., Schmidt 1921, Parenti 2003, Forsgren et al. 2020 [Chapter 6]). Due to their highly unusual morphology (Fig. 1), the species from family Molidae have attracted the attention of naturalists for many centuries (e.g., Steenstrup and Lütken 1898, Fraser-Brunner 1951).

Figure 1. Range of diversity in skeletal morphology in the molids (modified from Tyler 1980). (a) Ranzania laevis (Pennant 1776); (b) Masturus lanceolatus (Liénard 1840); (c) Mola mola (Linnaeus 1758).

This peculiar body plan is defined by numerous autapomorphic features (Fraser-Brunner 1951, Winterbottom 1974, Tyler 1980, Santini and Tyler 2002), most notably a short and rigid vertebral column and the loss of the swim bladder in adults, axial musculature, ribs, and pelvic and caudal fins. In particular, the posteriorly truncated appearance of these fishes is related to the disappearance of the skeletal components of a typical teleost caudal peduncle supporting a normal caudal fin; rather, these caudal peduncle components are replaced by a very deep and abruptly abbreviated tail region (Fig. 1), named the clavus by Fraser-Brunner (1951). From a skeletal point of view, the clavus is formed by a series of rod-like bones and fin rays situated between the posteriormost rays of the dorsal and anal fins. Johnson and Britz (2005) demonstrated that the caudal fin is completely lost in molids (except possibly for a few elongate rays at the center of the clavus in Masturus spp.) and that the skeleton of the clavus is formed by the modified posteriormost elements of the dorsal and anal fins; this hypothesis has also been confirmed by the cutaneous branch innervation pattern of the fin rays of the clavus, which is identical to that of the dorsal and anal fin rays (Nakae and Sasaki 2006). To compensate for the absence of a true caudal fin and caudal peduncle, molids rely on the dorsal and anal fins for swimming, using their considerably developed muscles that function as lift-generating wings (e.g., Watanabe and Sato 2008, Davenport et al. 2018, Watanabe and Davenport 2020 [Chapter 5]).

Because of their abbreviated body shape and habit of passively floating on the sea surface, the ocean sunfishes were historically regarded as slow-moving surface-dwellers that fed primarily on gelatinous zooplankton (e.g., Fraser-Brunner 1951, Hooper et al. 1973). However, recent studies have revealed that they are highly active animals undergoing considerable horizontal and vertical migrations, and that they have apparent ontogenetic dietary shifts in which young individuals feed benthically on a variety of prey, and adults are also capable of chasing fast-moving midwater prey (e.g., Nakamura and Sato 2014, Phillips et al. 2015, Nyegaard et al. 2017, Sousa et al. 2016, Sousa et al. 2020 [Chapter 8]). In fact, Masturus and Mola spp. are known to exploit a variety of food items (e.g., algae, seaweed, eelgrass, sponges, hydroids, jellyfish, ctenophores, molluscs, crustaceans, echinoderms, salps, and fishes; e.g., Weems 1985), while Ranzania spp. may have a diet that includes seaweeds (Barnard 1927, but perhaps only incidentally) as well as crustaceans and other invertebrates, small fishes, and even squid in a particularly diverse diet (e.g., Nyegaard et al. 2017).

Since the publication of the monumental “Le Régne Animal” by Cuvier (1817), molids have been grouped with pufferfishes (Tetraodontidae) and porcupinefishes (Diodontidae) within the Gymnodontes based on the shared possession of highly modified teeth incorporated into a parrot-like beak, and scales modified into several kinds of prickly spines and variously developed basal plates. Although the composition of gymnodonts has been modified since the time of Cuvier by the insertion of several fossil families or distinctive genera (e.g., Avitoplectidae, Balkariidae, Ctenoplectus, Eoplectidae, and Zignoichthyidae) and one extant family (Triodontidae), the existence of a close relationship between molids, pufferfishes, and porcupinefishes has been confirmed by a number of subsequent studies (e.g., Regan 1903, Breder and Clark 1947, Winterbottom 1974, Tyler 1980, Lauder and Liem 1983, Tyler and Sorbini 1996, Santini and Tyler 2003, Santini et al. 2013b, Arcila et al. 2015, Bannikov et al. 2017, Arcila and Tyler 2017).

The Molidae is one of the tetraodontiform lineages with the least known fossil record and it is based mostly upon isolated jaws and dermal plates (Santini and Tyler 2003). According to Tyler and Santini (2002), the scarcity of fossil molids results from the synergistic effect of two factors not conducive to fossilization, namely their pelagic habitat and the weakly ossified and spongy nature of their skeleton. The goal of this chapter is to provide an overview of the currently known fossils belonging to the family Molidae and to briefly discuss their evolutionary and paleoecological significance.

Skeletal Features and Fossilization Potential

The overall skeletal anatomy of the molids has been investigated in great detail by a number of authors (e.g., Gregory and Raven 1934, Gudger 1937b, Raven 1939a, 1939b, Fraser-Brunner 1951, Tyler 1980, Bemis et al. 2020 [Chapter 4]). While an adult molid’s most conspicuous skeletal feature is the posterior clavus which replaces the normal caudal fin and peduncle (Fig. 1C), they have a variety of additional remarkable anatomical features including: a large bone in the middle to rear of the interorbital septum that Tyler (1980) identified as a basisphenoid; a parrot-like beak mostly formed by a thick mass of osteodentine; large deep plates of firm cartilage that intervene between the bases of the dorsal- and anal-fin rays and their pterygiophores and their anteriormost larval vertebral element is incorporated ontogenetically into the basioccipital in at least two taxa (e.g., Tyler 1980, Britski et al. 1985, Santini and Tyler 2002, 2003, Britz and Johnson 2005). The molid ‘basisphenoid’ however, has been recently reinterpreted by Britz and Johnson (2012) as highly modified pterosphenoids because of its ontogenetic origin from the lamina marginalis of the chondrocranium, but this begs the question of what the bilaterally paired bones in the upper rear of the orbit identified by Tyler (1980) as pterosphenoids are. These persistent questions are examples of how much we still have to learn about molid skeletal morphology.

One of the most striking features of the molid skeleton is the considerable reduction of the bony tissue and the concomitant abundance of cartilage (Fraser-Brunner 1951). The bones are weakly ossified and characterized by a delicate fibrous or spongy texture, especially in the species of the genera Masturus and Mola (e.g., Gregory and Raven 1934, Raven 1939b). The reduced ossification of the bones, however, is associated with the possession of a sort of exoskeleton constituted by a continuous cover of scales, characterized by variably enlarged basal plates (Tyler 1980, Katayama and Matsuura 2016). These usually somewhat polygonal scale plates tend to bear a central tubercle, and are more or less in close contact with each other and bounded to the hypodermis (a thick subcutaneous collagenous tissue layer; labeled capsule in Davenport et al. 2018; Watanabe and Davenport 2020 [Chapter 5]) in Masturus and Mola spp. but form a robust and thickened carapace in Ranzania spp. (e.g., Fraser-Brunner 1951, Tyler 1980, Davenport et al. 2018). The skin of large-sized individuals of some species also exhibits other ossifications with a spongy texture that can reach considerable thickness (Watanabe and Davenport 2020 [Chapter 5]). In particular, a thick ovoid dermal plate (nasal plate) may be found on the snout just above the mouth and an elongate and thick subcylindrical bony plate (jugular plate) can be located on the chin, just below the mouth (e.g., Leriche 1926, Deinse 1953, Tyler 1980, Weems 1985, Carnevale and Godfrey 2018; Fig. 1). Additional dermal plates with high preservation potential can be observed along the posterior edge of the clavus in large-sized individuals of Mola spp. These “caudal” plates, called paraxial ossicles by Fraser-Brunner (1951), develop around the bifurcate distal ends of the fin rays and exhibit a different morphology and size based on their position along the clavus (Fraser-Brunner 1951, Tyler 1980), with the largest ones located in its medial portion and the smaller ones at its distal extremities. The anterior face of each of these plates has a longitudinal furrow that allows for the insertion of the membrane that connects the rays of the clavus, whereas their lateral faces are rough and notably rugose (e.g., Leriche 1926, Bemis et al. 2020 [Chapter 4]).

The parrot-like beak is one the most remarkable features of the Molidae, which has been traditionally used to associate them to other gymnodonts within the Tetraodontiformes. The upper beak consists of the fused contralateral premaxillae, whereas the lower beak is formed by the fusion of the two contralateral dentaries. These beak-like jaws are formed by a thick mass of osteodentine that overlies a basal unit of chondroid tissue (e.g., Britski et al. 1985). The biting edges of the beaks are toothless, without any discrete teeth or dental units visible. A triturating surface can be present posterior to the beak in the upper and lower jaws; however, the trituration teeth undergo extensive ontogenetic change (Tyler 1980), gradually decreasing in size and eventually disappearing in large specimens (see Weems 1985, K. Bemis unpublished data). There are taxonomically significant differences in the number, size, and morphology of the teeth in the known species, both extant and fossil (Tyler 1980, Weems 1985).

Due to their weakly ossified skeleton, rich in cartilage and characterized by a delicate spongy and fibrous texture, skeletal remains of molids are very rare as fossils, especially those pertaining to the genus Mola, while Masturus is completely unknown in the record. For this reason, most of the fossils unquestionably referred to in this group consist of isolated jaws and dermal plates.

The Fossil Record of the Molidae

Eomola bimaxillaria: Morphological Features and P...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Foreword

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Contents

- 1. Evolution and Fossil Record of the Ocean Sunfishes

- 2. Phylogeny, Taxonomy and Size Records of Ocean Sunfishes

- 3. Genetic Insights Regarding the Taxonomy, Phylogeography and Evolution of Ocean Sunfishes (Molidae: Tetraodontiformes)

- 4. Overview of the Anatomy of Ocean Sunfishes (Molidae: Tetraodontiformes)

- 5. Locomotory Systems and Biomechanics of Ocean Sunfish

- 6. Reproductive Biology of the Ocean Sunfishes

- 7. Ocean Sunfish Larvae: Detections, Identification and Predation

- 8. Movements and Foraging Behavior of Ocean Sunfish

- 9. The Diet and Trophic Role of Ocean Sunfishes

- 10. Parasites of the Ocean Sunfishes

- 11. Biotoxins, Trace Elements, and Microplastics in the Ocean Sunfishes (Molidae)

- 12. Fisheries Interactions, Distribution Modeling and Conservation Issues of the Ocean Sunfishes

- 13. Sunfish on Display: Husbandry of the Ocean Sunfish Mola mola

- 14. Ocean Sunfishes and Society

- 15. Unresolved Questions About Ocean Sunfishes, Molidae—A Family Comprising Some of the World’s Largest Teleosts

- Index