![]()

Part I

THE EARLY LUBITSCH—AN OVERVIEW

![]()

One

From Comic Actor to Film Director, 1914-1918

THE circumstances that prompted Lubitsch to pursue a career in film were more or less typical of the early silent cinema. Acting aspirations brought him to the theater, and the promise of money brought him to the screen. But it was a growing dissatisfaction with the lack of artistic control that stood behind his most important decision, the move from acting to directing. Lubitsch’s brief stage career was connected with Max Reinhardt and his famous repertory theater at the Deutsche Theater in Berlin. He was introduced to Reinhardt in 1910 by a mentor, the comic actor Victor Arnold, and immediately admitted into the ensemble. In the following years, Lubitsch played extras and bit parts, among them the second grave digger in Hamlet and Wagner in Faust, and he specialized in old-men parts, despite his young age.1 Like other Reinhardt actors, among them Emil Jannings, Paul Wegener, and Conrad Veidt, he developed an interest in screen acting when it was still considered a profession of ill repute. Because of his distinctive physiognomy, Lubitsch concentrated on comic parts, appearing in variety shows and, after 1913, in short slapstick comedies. He gave his most memorable stage performance as the hunchback in Friedrich Freska’s oriental pantomime Sumurun, a role that he played in the monumental Reinhardt production and his own film adaptation of Sumurun (1920, One Arabian Night).2 The years in Reinhardt’s ensemble had an enormous impact on Lubitsch’s formation as a filmmaker. In later years, he would frequently speak of the invaluable insights he had gained into directing, and the dramatic use of mass choreography in particular, by observing Reinhardt during stage rehearsals.3

Lubitsch made his first film appearance as Moritz Abramowsky in the lost one-reeler Die Firma heiratet (1914, The Perfect Thirty-Six), directed by Carl Wilhelm.4 If one can believe contemporary reviews, The Perfect Thirty-Six already contained the essential ingredients that would soon characterize Lubitsch’s own store comedies, including the focus on deception as a narrative and visual motif. Not surprisingly, many reviewers criticized the sympathetic portrayal of salesmen who deceived their female customers by selling larger clothing sizes as smaller ones. Such professional behavior, they seemed to argue, represented a most shameless indulgence in the cult of appearances and contributed indirectly to the decline of traditional moral values. For The Perfect Thirty-Six dared to portray deception as an essential part of human existence, even glorifying its association with modern consumerism. In so doing, the film laid the basis for Lubitsch’s later investigations of the relationship between appearance and truth, reality and simulation. During the years that followed, there was still a great variety in his roles and collaborations. Lubitsch appeared in a Max Mack film, Robert und Bertram (1915, “Robert and Bertram”) whose provincial setting and sentimental story of two vagabonds had a somewhat restraining effect on his acting style. For Fräulein Piccolo (1915, “Miss Piccolo”), he worked together with Franz Hofer, who was known for melodramas and sentimental love stories. In his own films, Lubitsch would also play a cuckolded husband, an unsuccessful physician, the conductor of a women’s chorus, a “Negerian” prince, and Satan himself. But the cultivation of a specific screen personality was the first step toward film authorship.

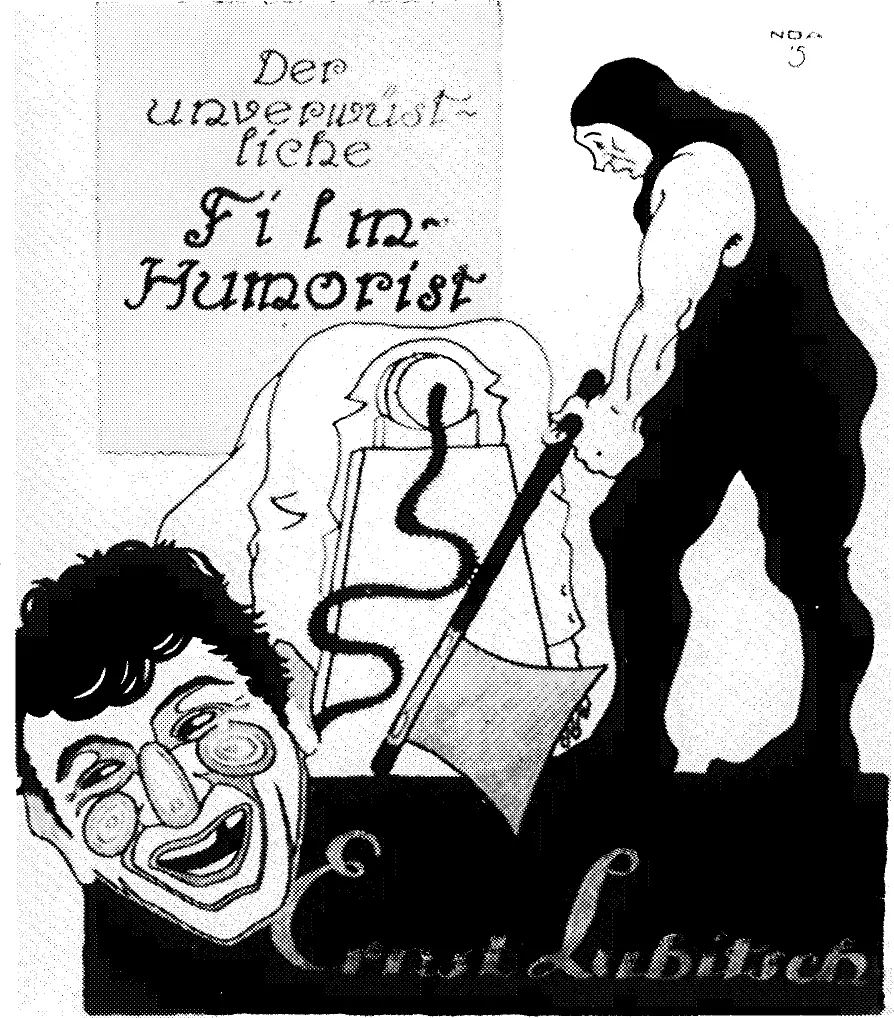

Gradually Lubitsch lost interest in old-men roles and, in a somewhat reverse order, entered the world of pubescent boys and eternal juveniles. Playing stock characters like Moritz or Meyer, he developed a screen persona that was as recognizable as that of French comic Max Linder or the Chaplin of the later Essanay and Mutual two-reelers (fig. 1). Though not stated openly, his characters are presumed to be Jewish, an assumption that is reinforced by the films’ quintessential setting, the clothing store. They are young apprentices with names like Moritz Rosenthal, Moritz Apfelreis, Sally Pinkus, Sally Katz, Sally Pinner, or Sally Meyer. Following in the footsteps of Siegmund Lachmann of Der Stolz der Firma (1914, “The Pride of the Firm”), Lubitsch’s antiheros usually arrive in Berlin from provincial places like Ravitch in Poznan. After a series of comic adventures, they conquer the nation’s capital and the shop owner’s daughter, convincing everyone through their irresistible charm and firm determination. Films from this series include (though unverified) Arme Marie (1915, “Poor Mary”), Der G.m.b.H. Tenor (1916, “Tenor Incorp.”) and Der Musenkbnig (1917, “The Blouse King”); unfortunately, no copies of these films have survived. However, it is in Doktor Satansohn (1916, “Doctor Satanson”), the three-reeler directed by Edmund Edel, that the actor Lubitsch defines most clearly the parameters of his play with desire and its fulfillment. Playing a physician (“a specialist for beauty care and body culture”) who promises his female patients eternal youth, provided that they never again kiss a man, Lubitsch appears in the film as a modern Mephistopheles figure. He controls the images and the process of imagination. When he appears in the older woman’s mirror, and leaves behind his business card, the scene functions like an advertisement for a film. The woman becomes his first victim in a seduction scene that depends crucially on his presentation skills but that would not take place without the desire of the other, the spectator. When Lubitsch lays down the rules of the transformation process (i.e., the taboo of physical intimacy), he also establishes the play of closeness and distance that constitutes all identification processes in the cinema. The moment when the doctor presents the rejuvenated woman in his magic transformation box anticipates the display of Cesare by Dr. Caligari. But here, the doctor’s creature is the product of her own desire, not of somnambulism; here the doctor’s accomplishment leads to humorous confusions, not destruction and despair. The overall atmosphere remains one of knowing detachment. Lubitsch even maintains his urbane perspective in somewhat unusual settings. A later film, Meyer aus Berlin (1919, “Meyer from feerlin”), shows the typical Berlin Jew who suddenly finds himself confronted with the adversities of nature, in this case the Bavarian Alps. Again role-playing proves to be essential, even if the regional costume—lederhosen, Tyrolian hat, climbing rope, and ice pick—seems strangely out of place in the luxurious resort hotel. And again imagination proves to be a key for his survival in foreign places. This is evidenced by a dream sequence in which Lubitsch “climbs” a mountain, the Watzmann, by simply eliminating two zeroes when a sketch of the mountain and an altitude mark appear (through trick photography) over his bedstead.

1. Film advertisement

Despite the commercial success of The Pride of the Firm, Lubitsch felt increasingly frustrated. He would later explain to Weinberg: “I was typed, and no one seemed to write any part which would have fitted me. After two successes, I found myself completely left out of pictures, and as I was unwilling to give up I found it necessary that I had to create parts for myself. Together with an actor friend of mine, the late Erich Schonfelder, I wrote a series of one-reelers which I sold to the Union Company. I directed and starred in them. And that is how I became a director. If my acting career had progressed more smoothly I wonder if I ever would have become a director.”5

Dissatisfaction, then, was the driving force behind Lubitsch’s first directorial efforts, the lost one-reeler Frdulein Seifenschaum (1915, “Miss Soapsuds”) and the three-reeler Schuhpalast Pinkus (1916, “Shoe Salon Pinkus”). Assuming the roles of author-actor-director, Lubitsch soon found himself in a situation where he was producing films as if on a conveyor belt. His films had such charming titles i&Der Kmftmeyer (1915, “The Muscle Man”), Der gemischte Frauenchor (1916, “The Mixed Ladies’ Chorus”) or Käsekönig Holländer (1917, “The Dutch Cheese King”), and they were often advertised in the following manner: “Theater owners! Get the one-reeler series with Ernst Lubitsch, the indefatigable film comedian. These comedies are a must for every program. Frantic laughter guaranteed. Projections Acticn-Gesellschaft Union.”6 Unfortunately, no copies of these films have survived.

The focus on class difference, including the desire for social recognition, points to the strong influence of ethnic comedy. This genre provided Lubitsch with his formulaic stories and stock characters, and its playful investigation of different cultural traditions contributed significantly to the sense of disrespect that made his one-reelers so successful with German audiences. Jewish humor provided a main source of inspiration, as is evidenced by Lubitsch’s self-deprecating acting style and the many references to the social and cultural milieu of the Konfektion (clothing manufacture); thus reviewers often described his films as “Jewish milieu piece[s].”7 It would be difficult, and perhaps futile, to look for biographical evidence such as visits to the theater or family traditions that would point to direct influences. However, one can find many similarities between Lubitsch’s humor and the diverse traditions that constituted Yiddish theater in the nineteenth century.8 Its origins reach back to the Purim play, a religious holiday and a celebration of spring. While based on Bible stories, the Purim play always included clowns and fools whose irreverent jokes and slapstick scenes disrupted the well-known narratives and created an atmosphere of exuberance and bliss. The fool’s sacrilegious attitude toward death and their unrestrained enjoyment of violence and destruction reveal the transgressive quality of the Purim play, both as regards the social order and moral conventions. Its characters resemble stock characters from the Italian commedia dell’arte, as well as the German Hanswurst and Picklehering figures; similarities to the Shrovetide plays can also be found. At the same time, the cultural and religious traditions of Judaism distinguish the Purim plays in important ways. Instead of trying to imitate life, the plays were staged in a presentational fashion, a reaction to the religious prohibition against making images. With their flat painted backdrops, conventional symbols, and symbolic actions they stood closer to popular spectacles than to the emerging bourgeois theater. The use of Yiddish, a jargon deemed unfit for literary writing, further underscored the proximity to popular entertainment, to what might be called shund (trash). At the same time, the limitation to a few Biblical episodes inevitably shifted the emphasis from dramatic configurations to questions of performance and style. Active audience participation was encouraged rather than quiet immersion in the characters’ psychological dilemmas. This penchant for commentary has an equivalent in the Talmudic method of scholarship, that is, of an ongoing process of interpretation and reinterpretation. In the context of the Purim plays, the self-referential play with the inherited and the known served affirmative functions but also cultivated a taste for puns and double entendres, thus introducing a distinctly intellectual quality. With the emergence of Yiddish theater, these traditions provided the mold in which new social experiences could be expressed in a humorous form. One recurring motif, the move from the country to the big city, can be found in many Yiddish plays from the late nineteenth century. Industrialization and growing anti-Semitism in Russia resulted in large waves of Jewish migration. Forced to leave behind the old communities, Eastern Jews were confronted with the task of surviving in a non-Jewish world while at the same time maintaining their cultural identity. Lubitsch’s store comedies restage this experience of the newly arrived immigrant in the urban spaces of Berlin. Similarly, Sally Pinkus and his accomplices combine character traits of the shmendrik, a stupid but shrewd young man, with the aggressive clumsiness of the schlemihl, who makes up for his social disadvantages through his knowledge of human foibles and the art of persuasion.

The presence of Jewish humor in the early comedies is closely linked to the awareness of difference. On the level of performance as well as in the choice of roles Lubitsch creates a distance and provides a framework that makes possible the expression of painful experiences. Humor provides a protective shield against social discrimination and a vehicle for dealing with ambivalent feelings about one’s social, sexual, and ethnic identity. It allows for the recognition of sorrow and suggests its overcoming through the liberating power of laughter. Thus humor becomes a weapon in breaking down boundaries; it turns the recognition of otherness into a shared experience, rather than a reason for separation and isolation. Nonetheless, Lubitsch’s references to Jewish culture remain problematic. For the popular appeal of his earliest films was also founded on the problematic conflation of ethnic and national characteristics—references to “the provinces” often concealed anti-Polish sentiments—and the heavily cliched opposition of provincial and urban life-styles. By playing with stereotypes, Lubitsch made them available to critical analysis. But by using them, his humor also stayed within the logic of such distinctions. Not surprisingly, Nazi film historians would later use Lubitsch as a main target for their anti-Semitic slurs—and try to exclude him from the history of German film. Writes Oskar Kalbus: “Today it seems incomprehensible that movie audiences, during the hard war years, cheered an actor who always played with a brashncss so alien to us.”9 Such discriminatory cxplicitness has found a counterpart in more recent critical assessments that seek refuge in vague generalities. For instance, Charles Silver uses the expression “very Old World, very Jewish, very male”10 to describe Lubitsch’s humor without specifying its implications. Other critics have deflected from the existence of an identifiable “Jewish style” by emphasizing the tension between European and American elements in his films. Here references to Lubit...