![]()

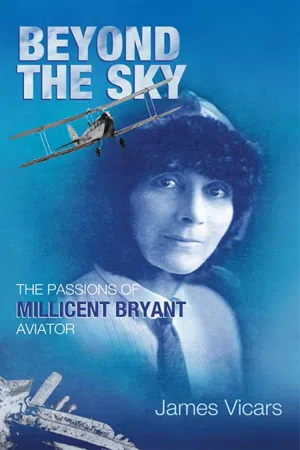

Part 1

The Aviator

![]()

1

First Flight

Early 1925

‘She’ll need cushions!’ the mechanic called out, flicking a lock of greasy black hair back from his face.

There was a ripple of laughter from the onlookers—a couple of other mechanics and the field manager—as Millicent made her own assessment of the seat. It was a metal bucket, sitting between the wooden sides of the forward cockpit. Low and snug. She put one foot on the wing, then swung the other over the fuselage and climbed in. It was definitely too low: she could see over the side easily enough but not through the windscreen. A few moments later, however, Edgar strode out of the shed and, sure enough, he had cushions under his arm.

‘You will want to see forward.’ He too was smiling as he handed across the cushions, one by one, until Millicent had boosted herself up high enough to see along the nose of the aircraft. Having only known him as a friend of George and Jack, her eldest and middle sons respectively, it was now curious to see him as Captain Percival … war pilot and commercial aviator! He was now showing a forceful, even imperious, side as he supervised the fuelling and checked the wing battens and struts. He and George had spent many hours designing, making and flying gliders, and George would, more than occasionally, join Edgar for a flight in one of the two AVRO 504 biplanes he’d picked up for a song in England after the war and shipped out to Australia.

‘Bring your coat, Mum,’ was all Jack said before they’d left for Richmond. Vague and breezy about the purpose of the excursion. All terribly casual. Yet it just so happened that a spare set of goggles and a small leather flying cap were somehow able to be found when they arrived at the airfield. He and Edgar were still chuckling at the success of their surprise as the plane was being readied.

Millicent watched these preparations keenly even before she got in. It ought to interest anyone, and was much like checking your motor car. But unlike her Citroën, this thing was a collection of fabric, wood and wires. It didn’t look particularly strong. ‘Held together’ were the words that came to her mind, but it was no time for doubts and fears. She was going up, no question about it. So she kept a close eye on everything from the checking of the motor under its cowling at one end to the testing of the tail-flaps at the other until it came time to take her place in the observer’s seat. Surprisingly, this was in the front cockpit: ‘That’s so there’s still a balance against the weight of the engine when only the pilot’s on board,’ Edgar explained.

He climbed in behind, and adjusted her earphones. ‘Ready for a flip?’

Millicent nodded, then remembered to give a thumb up.

They waited while the mechanic fiddled with the fuel system. He turned the prop one direction a few times until, finally, at Edgar’s signal, he gave it a heavy heave in the other direction. The motor didn’t catch but, when he heaved a second time, it did. Millicent was glad of the earphones and the muffling provided by the side flaps of the cap, as there was little else to be heard over the sound of the exhaust.

The rudder pedals and the stick between her legs began to move and, as Edgar throttled the engine, she could feel the air surging around them from the spinning propeller. It seemed to pull them along, and the machine began to roll forward. It eased to the right in a broad semicircle and began to bump over the grass as Edgar lined up the direction he wanted to take off. He opened the throttle and the roar of the engine and the draught from the prop increased simultaneously. The machine thrust forwards. They jolted along faster and faster, the uneven grass of the airfield hitting the wheels, rumbling and shaking through the frame, the metal bucket and even the cushions as the engine and the propeller strained to go faster. Suddenly the rumbling died away, and though she could see the ground still passing underneath, they were no longer touching it. There was a smoothness, the rush of air was more audible and, with a thrill, she realised they were now riding the wind.

The rooves of the airfield sheds appeared below as if she was seeing them from the top of a high building. They passed behind and, as the AVRO continued to climb, a skein of brown mist came back from the engine and kissed Millicent’s lips with what tasted like castor oil. There was only sky visible forward over the nose but, turning to the side, an instant’s giddiness struck her as she looked down and saw the emptiness of the space below. Nothing was holding them up except, somehow, the wind. Lifting her chin and looking around again, the giddiness vanished and was replaced by awe at the unexpected vastness of the horizon. As it dropped away at the corners of her vision, it was truly apparent that the earth was a globe, its flatness illusory. At the same time, the town below seemed to be shrinking into the country that surrounded it, the cultivated fields to the west giving way to the green folds and ramparts of the Blue Mountains as she’d never before seen them.

The wind buffeted Millicent’s face and clothing when she put her head out past the windscreen, but the feeling of space and of being borne upwards was exhilarating. She stretched out her hand and felt the air catch it and fling it aside. It was like riding a horse at speed, surging over the ground and hurtling over obstacles. And there was something akin to a horse in the finer movements of the aircraft, the little lifts of its head and flicks of its tail, before the stretch into a gallop. Seeing the Hawkesbury River glitter as they flew along it, the wingtips dropping down gracefully to trace each bend, brought her a surge of delight as another town came into view; a few moments later, they swept over the steeple of the church at Windsor.

Edgar descended a little as people on the river bank waved, and Millicent waved exultantly back to them in response. Then they rose gently again, turning back in a wide circle, following the river the way they’d come. All too soon, the airfield came into sight and the great vista stretching out towards the city on one side and the mountains on the other began to flatten as they came lower and lower. The landing strip seemed a rather smaller space than it had before, then suddenly they were almost on it and the aircraft slowed and seemed to pause. The engine died abruptly and, with a lurch, they touched down, bumped along the grass, and came to a halt. Jack came running across to meet them while Edgar climbed out and helped Millicent down. Her body seemed still to buzz with vibration and excitement.

‘Well, how was it?’ Jack called out, his voice suddenly loud as she removed the cap and goggles, but she could hardly stop smiling to tell him.

![]()

2

Second Flight

‘Thank you for coming. Please come in.’

The house no longer felt like home as potential buyers traipsed through. They whispered comments to each other but Millicent could hardly avoid picking up snatches now and again. She seemed to catch the women stealing glances in her direction, though the reason for the sale was hardly common knowledge. Yet there was a sting of sympathy in their looks. Could they know Ned and she were going their separate ways? Making their inspection, this or that husband and wife were pictures of propriety and ease and, when asking questions, seemed warmly, overly, polite. Unctuous. ‘Ah, lovely archway, ma’am …’ and ‘How the space welcomes one, Mrs Bryant, I do admire it …’

A couple stood talking by the big bay window, a silhouette of harmony framed like a wedding photograph. It recalled her father’s warnings of twenty-five years before, as well as the realisation that her youthful certainty had been just a kind of stubbornness. The marriage had gone sour after all, slowly but steadily. As the couple vacated the window to inspect other rooms, Millicent walked over and looked across the treetops. At least the sky was empty of her concerns. She felt again the exhilaration of the flight and the unbounded horizon, the lightness of being high above the earth. From up there, the solid house that preoccupied her now was tiny compared to the vast continent that flight brought within reach. She would go up again. She was determined. Turning back to the bounded interior, she knew she had to ignore the sideways glances. They were ignorant of her possibilities.

Still, it was a shock to have to exchange the spacious house and garden of ‘Grenier’, in the leafy suburb of Pymble on Sydney’s Upper North Shore, for something much smaller—and to be driven to it by necessity. For weeks Millicent went from agency to agency looking for something that would provide sufficient space for herself and the three boys. It wasn’t easy, but in June she finally found a flat in a block near the bottom of Shellcove Road in Neutral Bay on the northern side of Sydney Harbour.

‘It’s small,’ said George.

‘It’ll do,’ said Jack.

Then again, Jack, her more warm and communicative middle son, was leaving before they were due to move in. He was going to England to look for commercial agencies in the dairy industries. This was an achievement in itself: when he first proposed the idea, there were few resources to get him there. Not from his mother, at that point. And there was cold comfort from his father, who called the idea ‘pretty ambitious’.

‘Maybe, Dad,’ Jack had replied. ‘But you know it’s what interested me at College. The industry here could really develop.’

‘I think you’ll be better getting some money behind you first. Build up some funds so you’ve got something to fall back on.’

This was typically unadventurous of Ned, though Millicent too had her doubts. However, when a neighbour pointed out smugly that ‘beggars can’t be choosers’, she came straight down on Jack’s side and began to look for ways he could obtain passage. But in the event, his own efforts bore fruit: he was taken on as a greaser on the Commonwealth and Dominion Line’s steamship, Port Hunter, which was soon to sail for England via Ceylon and Suez.

‘They said I’d be working in the heat and steam of the engine room,’ Jack told them over one of the last dinners they shared before his departure. ‘And was I conversant with machinery? Well, by the time I finished telling them about fixing and maintaining that damned lorry, their heads were nodding.’

‘Told you, didn’t I?’ said George, waving his finger. ‘Lucky you’re not still stuck somewhere between here and Richmond with the carburettor in pieces and a load of cabbages rotting in the back. Thank God it’s finally up for sale.’

‘Well, it got me “engineering” qualifications a lot quicker than you got yours!’

But his impending departure created a further flurry of preparations, starting with letters to family in England so they’d get there ahead of Jack himself, and these overlaid the more complicated efforts already in train for the house move. The sailing date thus arrived in a blur, all too soon somehow, and as they drove to the dock at Darling Harbour, Millicent thought, I’m not ready for him to go. It’s too much to lose him just now. But as they stood for tremulous moments among the ropes and bollards, with coal smoke scenting the air, she determined to replace tears and apprehension with enthusiasm, remembering they’d agreed to write at least weekly.

‘I’ll be so excited to hear your progress. We’ll all feel like we’re travelling with you!’ she said, hoping her gaiety didn’t waver as she put her arms out. But Jack hugged her fiercely.

‘Don’t spare any detail of things at home then, Itz. I want to hear it all from you,’ he whispered. He broke away abruptly, shook hands with his brothers and strode up the gangway with his duffel bag and suitcase, barely pausing at the top for a quick wave before disappearing inside.

She could allow some tears then. And back in the car, with just Bowen and George and no home that felt like their own, the world seemed smaller. As if it, too, had slipped its anchor and was floating towards the horizon. So Millicent sat down and wrote that very evening, and the first letter to Jack, dated Saturday July 13th, 1925, was finished almost before the Port Hunter had cleared Sydney Heads and turned south.

There was actually little time for writing, and the sleep it frequently cost added to her exhaustion. Still, she wrote every few days. It enabled her to pause and reflect, and, in the beginning, was a way she could assimilate both the emotionally-charged event of Jack’s departure and the leaving of ‘Grenier’.

Because, as the house emptied, it was not yet with the feeling of looking forward. Instead, there was the feeling of abandoning belongings and furniture that had marked their passage, each with its particular memories. There would be no place at Number 6, Rycroft Hall, for the family dining table or some of the familiar armchairs, the two potted palms or the larger bookcase Ned had left behind. They’d have to be piled in a corner until Lawson’s could take them away for auction.

The garden had died back during the winter but neither had anything much been done in it for months. Under listless, cloudy skies it felt like a ruin, and at its edge a bonfire burned all day consuming the detritus of the years they’d spent there in venal flurries of cinders and smoke. Millicent felt more and more nauseous with each load flung into the flames, and when she finally took from that locked desk drawer the packages of letters that had nourished her inwardly for so many years, the bile rose in her throat. Once it would have seemed impossible, but in an abrupt movement she scooped up the whole pile, hesitating only a moment before tossing it on. As the flames turned the thin paper to black, she glimpsed pages with his writing appearing, curling up and disappearing. A stab of the pain passed through her, like a moment of the longer anguish that had come with the end of those deepest, dearest hopes. She turned away quickly from the heat, gulping in fresh air and grateful for the many other tasks at hand. And there was still more for the fire.

It wasn’t until the end of July that Millicent, George and Bowen finished settling into Rycroft Hall. There had been weeks spent unpacking, repacking, storing and laying linoleum, but that wasn’t the end of it: even though their daily rhythms seemed more or less the same they were all at closer quarters in the flat. And there were ‘adjustments’ Millicent simply had not anticipated.

There was George, for one. His degree in Engineering had quickly landed him a good job after finishing at Sydney University but it seemed hardly to challenge him. He would arise as late as possible in the morning, gulp down some tea and maybe some bread and jam, and leave with barely a word. A grunted acknowledgment perhaps. And rarely any sign of what time he expected to be home for dinner. Or if he would. Bowen, six years younger, was far more considerate. However, with growing school sports and other commitments, he was beginning to lead an increasingly busy life too.

Beyond, there was Ned. Husband and father. He now lived elsewhere, a resolution to the tensions built over many years that had made remaining together intolerable. As ever it was she who’d finally acted, but while the separation was only informal, it somehow created ripples and disjunctions that she hadn’t foreseen. Of course, it was awkward with Ned’s family, of which Alice and Charles Bryant had been the closest, but also with one or two members of her own family, the Harveys, who’d not approved of her actions.

But more unexpected was the change in her social station. Equally unofficial, it was communicated in the form of silence from many of those who had regularly sought out her company at drinks or around the dinner table. The Duttons. The Rosses. There were also more direct ...