- 166 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Animal Tracks and Hunter Signs

About this book

Within this volume Ernest Thompson Seton attempts to recount the actions and interactions of various woodland critters from their tracks alone. From a weasel racing across the snow after its prey to hungry wolves themselves stalking a moose, Seton imparts the basics of animal tracking in this half-instruction manual half-exciting narrative designed to inspire children. Ernest Thompson Seton (1860 – 1946) was an English author and wildlife artist who founded the Woodcraft Indians in 1902. He was also among the founding members of the Boy Scouts of America, established in 1910. He wrote profusely on this subject, the most notable of his scouting literature including "The Birch Bark Roll" and the "Boy Scout Handbook". Seton was also an early pioneer of animal fiction writing, and he is fondly remembered for his charming book "Wild Animals I Have Known" (1898). Other notable works by this author include: "Lobo, Rag and Vixen" (1899), "Two Little Savages" (1903), and "Animal Heroes" (1911). Many vintage books such as this are becoming increasingly scarce and expensive. We are republishing this book now in an affordable, modern, high-quality edition complete with a specially-commissioned new biography of the author.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Animal Tracks and Hunter Signs by Ernest Thompson Seton in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Zoology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 The Oldest of All Writing

“I wish I could go West and join the Indians so that I should have no lessons to learn,” said an unhappy small boy who could discover no atom of sense or purpose in any one of the three Rs.

“You never made a greater mistake,” replied the scribe, “for the young Indian has many lessons to learn from his earliest days—hard lessons and hard punishments.

“With him the dread penalty of failure is ‘go hungry till you win’; and no more important task has he than his reading lesson.

“Not just twenty-six characters are to be learned in this exercise, but a thousand. Not clear straight print are these characters, but dim, washed-out, crooked traces. Not indoors on comfortable chairs are the lessons, with a wise and patient teacher always near, but out in the forest, often alone, and in every kind of weather.

“There he slowly deciphers the letters and reads sentences of the oldest writing on earth—a style so old that the hieroglyphs of Egypt, the cylinders of Nippur, and the drawings of the cave men are as things of today in comparison; a writing indeed that is older than mankind, the one universal script. I mean the tracks in the dust, the mud, or the snow.

“These are the inscriptions that every hunter, Red or White, must learn to read infallibly. And, be the writing strong or faint, straight or crooked, simple or overwritten with many a puzzling diverse phrase, he must decipher and follow swiftly, unerringly, if there is to be a successful ending to the hunt which provides his daily food.”

This is the reading lesson of the young Indian, and it is a style that will never become superseded.

The naturalist also must acquire some measure of proficiency in the ancient art. Its usefulness is perennial to the student of wildlife; without it he would know little of the people of the wood.

It is a remarkable fact that there are always more wild animals about than any but the expert has any idea of. For example there are, within twenty miles of New York City, fully fifty different kinds, not counting birds, reptiles, or fishes, at least one quarter of which are abundant. Or, more particularly, within the limits of Greater New York, living their free and normal lives, there are at least a dozen species of wild beasts, half of which are quite common.

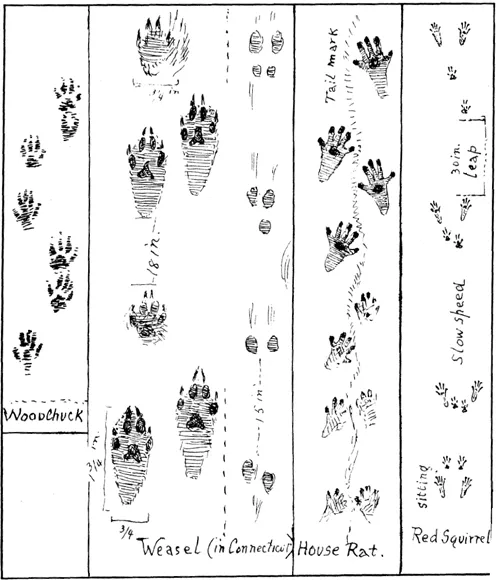

To illustrate: along the shores of Staten Island and Long Island one will surely find Mink, Muskrat, and Coon, not to mention Bats. In the woods will be Gray Squirrels, Red Squirrels, Flying Squirrels, Chipmunks, Moles, and Shrews. Around the farms and other homes, House Rats, House Mice, and Deer Mice would abound. Possums, Woodchucks, Skunks, and Weasels are occasional, and a number of others make their appearance here and there.

“Then how is it that we never see any?” is the first question of the incredulous. The answer is simple.

Tracks near the barn

Long ago the beasts learned this dire lesson: Man is your worst enemy; shun him at any price. And the simplest way to do this is to come out only at night. Man is a daytime creature; he is blind in the soft half-light or darkness that most beasts prefer.

While many animals have always limited their activity to the hours of twilight and gloom, there are not a few that were once diurnal, but have given up that portion of their working day in order to avoid the archenemy, man.

Thus they can flourish under our noses, and eat at our tables, without our consent or even knowledge. They come and go at will, and the world knows nothing of them. Their presence might long be unsuspected, but for one thing, well known to the hunter, the trapper, and the naturalist. WHEREVER THE WILD FOURFOOT GOES, IT LEAVES BEHIND IT A DETAILED RECORD OF ITS VISIT. This it puts down in the ancient script of the woods, the script of the footmark trail, the story of at least a portion of its life.

Each of these dotted lines is a wonderful record of the creature’s activity during the time it was there. It needs only the patient work of the seeker to decipher that record and from it learn much about the animal that made it; yes, even without that animal ever having been seen by him.

Savages are more skilled in this art than are civilized folk, for tracking is their serious lifelong pursuit, and they have not injured their eyes with books. Intelligence is, indeed, important here as elsewhere; yet it is a remarkable fact that the lowest race of mankind, the Australian blacks, are reputed to be by far the best trackers. Not only are their eyes and attention developed and disciplined, but they have retained much of the scent power that civilized man has lost. They can follow a fresh track, partly at least, by smell.

Woodland and marsh life

2 Tracking, Trailing, or Spooring

The first lesson of a young hunter, after knowing the animals themselves, is recognizing their tracks. He must not only recognize them, however; he must learn to follow them and read the information that they offer.

As I have already said, tracks are the oldest writing in the world. We have track records that are millions of years old; the track is there long after the creature that made it is dead and gone, even wholly extinct.

But the most useful track records for us today are those that we find in the dust, or better still the snow.

Since the trail is the unquestionable story of the wild being at that time, one should lose no chance to study and record the tracks of animals if he wishes to be a real naturalist.

Whether one specializes in birds, beasts, stars, diseases, microbes, metals, or tracks, the first step in knowledge is exact identification.

The expert hunter after quadrupeds that frequent the woods gets information and guidance from passing glimpses of the animal, the information supplied by the dung pellets, the marks that it makes in feeding on or scratching the bark and brush of trees, the sounds that it makes by voice or by attacks on tree trunks, the cries of birds that are aroused by its presence and call in protest or in signal to other birds.

But by far the most important sources of information are the tracks that the creature makes as it travels or maneuvers in the soft earth, the mud, or the snow of its haunts. The tracks tell exactly when and where the creature passed, its species, its size and mood, whether old or young, sometimes even its sex, whether alarmed and flying for safety, or dozing in calm repose. It tells all about the animal, and more fully than in any other way, except by a clear view close at hand —such a view indeed as is rarely secured for more than a few seconds, while the track record covers the life of the creature for hours, sometimes for days.

It is hard to overvalue the power of the skillful tracker. To him the trail of each animal is not a mere series of similar footprints; it is an accurate account of the creature’s ways, habits, changing whims, and emotions during the portion of life of which the record is in view. These are indeed autobiographical chapters and differ from some other autobiographies in this—they cannot tell a lie. We may get wrong information from them, but it is our own fault if we do; we misread the unimpeachable document.

Furthermore, under the proper conditions, the track record is imperishable. We need not be on the spot when the writings were made. We have in the rocks today track stories that were told, then in the mud, a million years before man appeared on this planet.

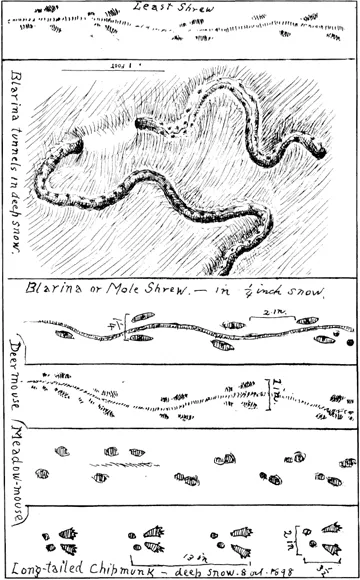

The ideal time for tracking, and almost the only time for most folk, is when the ground is white. After the first snow the student walks forth and begins at once to realize the wonders of the trail. A score of creatures whose existence, maybe, he did not know of are now revealed all about him, and the reading of their life histories becomes easy.

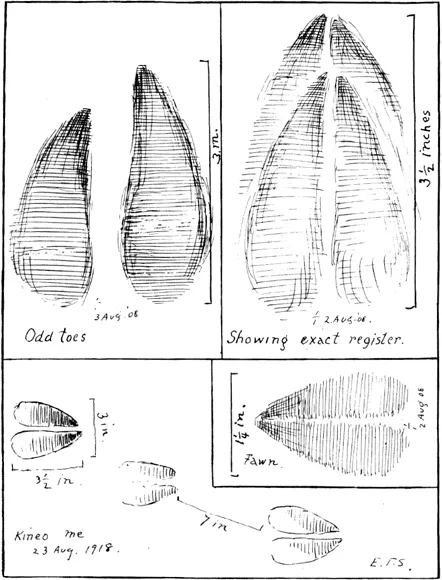

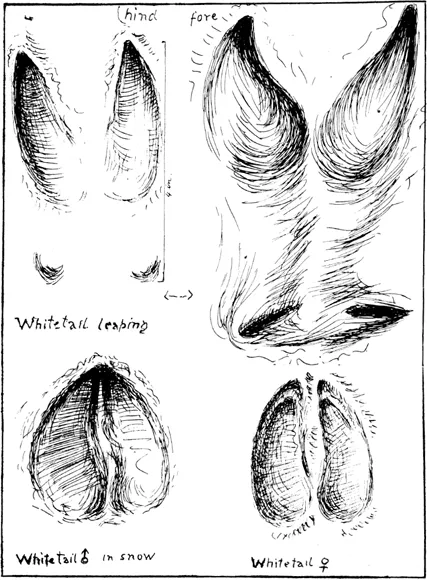

Whitetail Deer tracks

It is when the snow is on the ground, indeed, that we take the census of the woods. How often we learn with surprise from the telltale white that a Fox was around our hen house last night, that a Mink is living even now under the woodpile, or that a Deer—yes! there is no mistaking its sharp-pointed unsheeplike footprint—has wandered into our woods from the farther wilds!

Never lose the chance of the first snow if you wish to become a trailer. Nevertheless, remember that the first morning after a night snowfall is not so good as the second, for most wild creatures “hole up” during the storm; the snow hides the tracks of those that do go forth; and some actually go into a “cold sleep” for a day or two after a heavy downfall accompanied by severe frost. But a calm, mild night following a storm is sure to offer abundant and ideal opportunity for beginning the study of the trail.

It is a most fascinating amusement to learn some creature’s way of life by following its fresh track for hours in good snow. I never miss such a chance. If I cannot find a fresh track, I take a stale one, knowing that, theoretically, it is fresher at every step, and, from practical experience, that it always eventually brings one to some track that is fresh.

Although so much is to be read in the wintry white, we cannot at that time make a full account of all the woodland fourfoots, for there are some kinds that do not come out in the snow; they sleep more or less all winter.

Deer in action

Thus, one rarely sees the track of Chipmunk or Woodchuck in truly winter weather; and never, so far as I know, have the trails of Jumping Mouse or Mud Turtle been seen in the snow. These we can track only in the mud or dust.

Such tracks cannot be followed as far as those in snow, simply because the mud or dust does not cover the whole country; but they are often as clear and in some respects more easy of record.

Here are some of the important facts to keep in view when you set forth to master the rudiments of trailing, or “spooring,” as our English friends call it.

FIRST: No two animals leave the same trail; not only each kind but each individual at each stage of its life leaves a trail as distinctive as the creature’s appearance. It is obvious that they differ among themselves just as do we, because the young know their mothers, the mothers know their young, and the old ones know their mates, even when scent is clearly out of the question.

SECOND: The trail in its entirety was begun at the birthplace of that creature, and ends only at its death. It may be recorded in visible track or perceptible odor. It may last but a few hours and may be too faint even for an expert with present equipment to follow. But evidently the trail is made, wherever the creature journeys afoot.

THIRD: It varies with e...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Copyright

- Ernest Thompson Seton

- Title

- Note to the Reader

- 1. The Oldest of All Writing

- 2. Tracking, Trailing, or Spooring

- 3. On Making Track Records

- 4. The Coon That Taught Me How

- 5. Black-Tracks

- 6. Trailing as the Hunter Does It

- 7. A Rabbit Adventure

- 8. Around an Eastern Farm

- 9. Marsh and Woodland Creatures

- 10. Track History of Mink and Rabbit

- 11. Record of a Woodland Tragedy

- 12. Out West

- 13. A Chapter of Fox Life

- 14. Tracks in Town

- 15. The Skunk and the Unwise Bobcat

- 16. The Dude on the Trail

- 17. Dabbles the Coon

- 18. Deer and Antelope Tracks

- 19. Some Northern Animals

- 20. Scats or Signs

- 21. Bear Trees and Other Animal Signs

- 22. Blazes and Indian Signs

- 23. Blazes Used in Town

- A Final Word

- Index