![]()

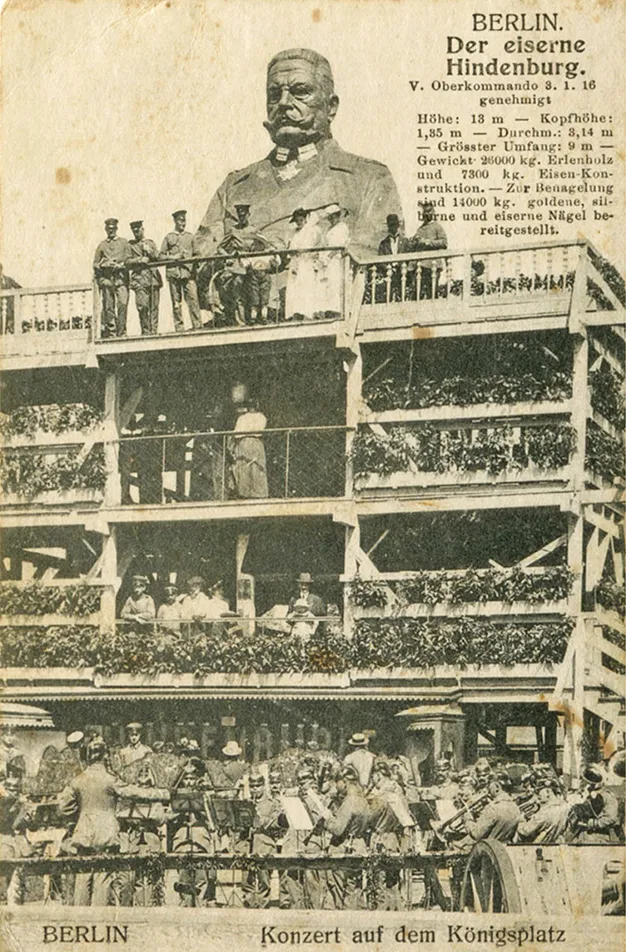

During 1914–15, with the financial implications of the war effort impacting on government coffers, the German Empire (as it then was) embarked on a ‘men of iron’ project. A series of wooden sculptures of heroic figures were set up in major cities. For an appropriate donation, citizens could purchase a nail and hammer it into the plinths of the memorials, recording their contribution to the national cause. The most dramatic example was a 42-foot (12.8 metre) wood sculpture of the popular war leader Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg by the sculptor Georg Marschall erected in the Königsplatz next to the Reichstag in the Prussian capital of Berlin (Fig. 1.1). It was inaugurated in September 1915. Different levels of donations were recorded by the materials of which the nails were made: iron nails (5 deutschsmarks each), silver (10 deutschsmarks) and gold (for higher sums).

Several things were different about this commission. First, Hindenburg was a living war hero, thus breaking with the tradition of only commemorating the heroic dead. He had led the German forces in the successful battle of Tannenberg defeating the Russians in the opening year of the war. Second, unlike the similar ‘men of iron’ elsewhere, scaffolding was erected as the nails began to cover the lower levels of the vast sculpture and spread upwards from the plinth onto the figure itself. Donors were thereby permitted access to the upper levels where they would mark their backing of the war effort with a nail on the body of the sculpture. Though the process of nailing seems to have stopped when the coverage approached the head, the fact that the bulk of the sculpture should have been treated in this manner at all attracted a certain amount of criticism in Germany itself from those with more traditional artistic tastes.1

Outside Germany, the Hindenburg statue was a gift to wartime publicity. On Christmas Day, 1915, the Illustrated London News devoted a double-page spread to the nailing craze, adapting a German newspaper article with appropriate illustration and adding its own editorial comment. Quoting one of its correspondents, the paper remarks:

The answer to the riddle was ‘furnished by a wooden idol in the British Museum’. Illustrations show a nailed figure in the British Museum and originally from the Kongo people who occupy the coastal region of what is now Angola, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and the Republic of Congo. Alongside the British Museum piece is a similar example from the Royal Geographical Society described in its nineteen-century accession details and in the title of a watercolour by the Victorian painter Thomas Baines of its ‘capture’, as a ‘war fetish’. The nailing, it is suggested, is not in fact a perverse attempt to do harm to a national hero—least of all, to a living one—though that is how it was seen by critics in Germany. Rather, the newspaper article argues, it represents a misguided appeal to a great military leader to confront the wrongs inflicted on fellow countrymen by a hated foe, just as driving a nail into a Kongo figure is—in one understanding—a means of identifying and killing a witch.3

Though there is no reason to think that in Germany an association of the Hindenberg statue with Congolese nailing practices was commonly taken up, the point was developed in Britain. In an accompanying comment, the German psyche and ‘kultur’ are openly ridiculed for not having yet evolved to the level of ‘the more advanced natives of West Africa’. The racial stereotyping is echoed in a wartime pamphlet entitled The Wooden Idol of Berlin where the comparison led to the conclusion that the Germans are ‘white negroes’—a version of an allegation which was often made against German expressionist artists in Germany itself, some of whom—Ernst Kirchener, for example—were not discouraged by being described as ‘primitives’. This is, further, an instance of a common propaganda description of German acts of wartime destruction as indicative of inherent barbarism, such as the ‘deliberate’ shelling of Reims Cathedral in 1914.4 The Hindenburg statue is described as a ‘monstrous pin-cushion’ in front of which, the parody continues, ‘the chief men of the tribe, adorned with their best feathers’ parade ‘executing a sort of religious dance which they curiously call “the Goose Step”’.5 Beyond the war of words, the ‘men of iron’ initiative was also lampooned in satirical reconstructions of the nailing process itself. At a charity event in Stepney in London a version of the Hindenburg monument was put up and nurses from the nearby Mile End Hospital were photographed on a ladder hammering nails directly into the head of the crudely constructed adaptation. Their purpose was also to raise war funds, this time for British ‘brave and wounded soldiers’. But, clearly, in this case the intention in knocking nails into an image was to mock the entire rationale behind the project and, by implication, reverse German intentions and do harm to its living subject, Hindenburg himself—and by extension his countrymen.6

That the ‘men of iron’ project was capable of being inflected in divergent ways is inextricably linked to the idea of ‘the fetish’—of which Kongo nailed figures were a classic example—being deeply embedded in European thought. While the term has come under a great deal of scrutiny and been subject to revision or replacement in a number of contexts, there have also been arguments for its retention as a viable description of the agency attributed to certain objects and the responses to them. In exploring how such objects have been understood in academic and curatorial circles, the focus in this chapter will principally be on Kongo minkisi (sing. nkisi) a generic category of which the nailed figures, minkondi (sing. nkondi), are one example. In museums and catalogues, the way of referring to minkisi has gradually slipped into the use of a different vocabulary as they have been more fully understood. Even so, they retain a significance which still resonates with contemporary visual artists if—like Congolese or African American painters, sculptors and conceptual artists—they have some sense of direct linkage. For other artists with no connection, referencing minkisi is still a way of invoking a particular cultural or psychological condition which, in reality, may have little to do with the original intentions of their makers, operators and clients. The work of William Pietz, in particular, has exposed both the longevity and the tenacity of the fetish idea which, he argues, has roots in the encounters between Europeans and Africans along the western Atlantic littoral in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.7 Indeed, his contention is that the association of the idea with certain classes of objects derives precisely from the character of these coastal interactions. The disjunctions between the things that were valued by Europeans and by the African intermediaries with whom they conducted commercial relationships was a source of much conjecture. Gold was highly valued by all sides, yet it could be acquired for goods that Europeans regarded as trinkets. Likewise, the apparent attribution of active spiritual and healing properties to materials and objects apparently assembled randomly implied a mistaken appreciation of the properties of things. As described by Pietz, the idea of the fetish emerges from a combination of these characteristics: a seeming inconsistency or ineptitude in the attributing of value and a radical misunderstanding of the principles of causality. ‘The fetish’ is a tendril that weaves its way back and forth through different crevices in European thought, something at times perverse and menacing, at times finding fertile soil in Western imaginings.

In the latter part of the nineteenth century, the pioneering anthropologist E. B. Tylor discussed fetishism as a development of the concept of animism, an idea which has since been extended to explore the attribution of an inherent ‘personhood’ and ‘agency’ to certain classes of object.8 From there attention focused on a language of obsession, desire, idolatry and worship. As such, the term found its way into the vocabulary of Marxist economics, Freudian psychoanalysis,9 and early anthropological and art historical writing. Marxists adopt the term ‘commodity fetish’ to characterize the ascription of value to an object in virtue of the labour expended in its production rather than its inherent properties; Freudians talk of ‘sexual fetishism’ to reference the displacement onto an object of the fears of castration in childhood (indeed of boyhood). It was used by missionaries and colonizers in a derogatory sense to promote their projects of conversion and control as improvements on what was portrayed as an otherwise degenerate condition. Later, it would be adopted by surrealist writers and artists with a subversive intention. Thus, at the time the French authorities organized a major colonial exhibition in Paris in 1931, an alliance of communists and surrealists mounted an alternative anti-colonial display including a display case devoted to ‘Fétishes Européens...