- 206 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Understanding Photojournalism

About this book

Understanding Photojournalism explores the interface between theory and practice at the heart of photojournalism, mapping out the critical questions that photojournalists and picture editors consider in their daily practice and placing these in context. Outlining the history and theory of photojournalism, this textbook explains its historical and contemporary development; who creates, selects and circulates images; and the ethics, aesthetics and politics of the practice. Carefully chosen, international case studies represent a cross section of key photographers, practices and periods within photojournalism, enabling students to understand the central questions and critical concepts. Illustrated with a range of photographs and case material, including interviews with contemporary photojournalists, this book is essential reading for students taking university and college courses on photography within a wide range of disciplines and includes an annotated guide to further reading and a glossary of terms to further expand your studies.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

What Is Photojournalism?

Chapter summary

In this chapter, we begin by considering photojournalism's contexts from a variety of perspectives: the wider network or economy in which is it located; the cultural and social perceptions of truth to which it is still, for better or worse, held accountable; and, ultimately, how it can be defined as all of these parameters shift and change with the transformations of the contemporary media environment. This involves considering some of the inherited stereotypes and perceived values associated with the photojournalist as a figure within this environment. Finally, as a way of further introducing the priorities of the book as a whole, we discuss the relationship between theory and practice in relation to photojournalism, including the imperative for viewers and photographers alike to commit to visual literacy, or a position of critical engagement with what we see.

The multiple levels of photojournalistic witnessing

On a street in Sorocaba, Brazil, a man takes a photograph. His subject is another man taking a photograph, of a painting, of a photograph. Four days earlier, Alan Kurdi, a three-year-old Syrian refugee of Kurdish ethnic background, drowned in the Mediterranean Sea. He and his family were trying to reach Europe (reportedly they hoped eventually to settle in Canada). Turkish photojournalist Nilüfer Demir took a set of photographs of his lifeless body washed up on the shore, which quickly spread around the world (Figure 1.1). Reproduced on newspaper front pages and in social media feeds, the image of this small boy lying face down in the sand stopped people in their tracks. It led to cries of outrage, horror, grief and shame. It was appropriated and transformed into artworks, memes, tributes and protests that took on 'lives' of their own, and most of which communicated a plea for compassionate action in response to the growing global refugee crisis in which thousands of people were arriving every day on the shores of Europe, in many cases having fled the terror of war, but all in search of a better life. Alan Kurdi became a symbol of something that transcended the individual tragedy of his death, and that led to change. At the level of government policy in Britain, Turkey, Germany and other European nations, the change is debatable. But in the lives of individual citizens of those countries, there can be no doubt: because of Demir's photographs, ordinary people in ordinary towns have, at the time of writing, Syrian families sleeping in their spare bedrooms and eating at their tables, and there has been a surge in financial donations to migrant and refugee charities. So profound was the empathy stirred up by these photographs that many people could no longer, in good conscience, regard the refugee crisis as a faceless abstraction.

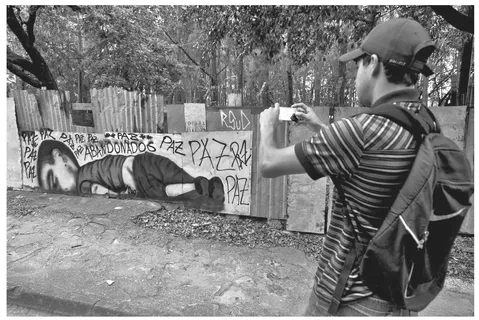

Figure 1.1 Nelson Almeida, 2015. A man takes a picture of graffiti depicting Alan Kurdi (initially reported as Aylan Kurdi, and also known as Aylan Shenu), a Syrian three-year-old boy who drowned off a Turkish beach, in Sorocaba, Brazil, on 6 September 2015 (Getty Images).

Nelson Almeida's photograph (Figure 1.2) records one of the many vernacular artworks that proliferated around the world in response to the photographs, painted and stuck to a fence in a Brazilian city. In it, the same boy's small body has been made monumental, and is surrounded, in scrawled text that appears frantic, repeated and desperate, by the word 'peace'. Alan Kurdi and the many thousands of other Syrians like him have been 'abandoned' by the governments of the world's most powerful countries, if not (for this short time at least) by their news media. This photograph captures in its numerous layers of witnessing a dimension of contemporary photojournalism that sets it apart from that of previous generations. In a striking echo of Demir's original photograph, a man stands nearby and bears witness, this time not as a uniformed Turkish policeman but as a citizen photographer in a backpack and baseball cap, likely poised to share his camera-phone image via Instagram or Facebook in a kind of tribute of his own - not weeks or months following the appearance of Alan Kurdi's body on a beach on the other side of the world but within just four days. He is part of a network of witnesses, the same network as Demir, Almeida and the anonymous graffiti artist, through which images travel, effecting the kind of recognition for which photojournalists have worked over generations, but with a speed, ubiquity and proliferation that has not been imagined before.

Figure 1.2 Nilüfer Demir, 2015. A Turkish police officer stands next to a migrant child's dead body off the shores in Bodrum, southern Turkey, on 2 September 2015 after a boat carrying refugees sank while reaching the Greek island of Kos (Getty Images).

Together, these two images set the scene for the concerns of this book. One is a photograph that records the essence of a vital and complex historical moment in a way that seems to exceed words; it is a potent symbol that will no doubt before long be called 'iconic', and the impact of which has been deeply felt throughout Europe and beyond (more deeply, we would argue, than any other in recent memory). The other presents in palpable terms - the street, the human observer, hand-drawn imagery and hand-held smartphone - how the contemporary networked digital media economy transcends the boundaries that have governed it in the past while still preserving, if not enhancing, photography's unique capacity to move hearts and minds in response to the most pressing issues of the moment. Both of these images raise complicated and problematic moral questions about the representation of the other, and of the aftermath of acts of violence, and demand that ethically supportable solutions to them be explored. Central to the concerns of this book are the multiple levels of witnessing and representation that can be seen within these two pictures, including the historical and moral contexts that surround the photographing of death and suffering, and the complex conditions of viewing and dissemination.

The economy of images

The distinct features of the still photograph endow it with a unique quality in that it acts as a technologically enhanced, proxy form of vision, positioning the viewer as a witness of the scene with their own eyes, even if separated spatially and temporally from the actual event. The act of photography therefore links together the event, its participants (including both the photographer and any subjects of the photograph), the photograph itself and then its audience, in an active, ongoing and participatory process of producing meaning. In doing so, photographs provide a kind of raw material for the construction of historical consciousness. They have a remarkable ability to define events and mediate their passage into history. This action does not happen in just one direction: it ebbs and flows as the significance of a particular image changes over time, and is recalled by later events that echo or contrast with it, or recedes into memory.

This movement and flow of imagery can be called a network, as noted above (and explored further in the last chapter of this book). It can also be understood as an economy. Photographs, such as that of Alan Kurdi, go through complex processes of distribution, trade and consumption, and are perceived to have a different kind of value in different contexts. Photographs are also economic in that they are commodities of commerce, bought and sold as part of the commercial activity of selling newspapers, magazines and, increasingly, online publications. But they are also commodities of information, meaning and knowledge production; memory; and ultimately of culture. In the economy of photojournalism information, ideas, opinions, news, propaganda and commerce all interact. Their meanings are altered depending on the context in which they are printed and by the way in which they are presented. They have simultaneously an informational and a monetary value in that they convey meaning but also help sell the product in which they are embedded. As commodities of both informational and commercial exchange, they are vulnerable to the fluctuations of marketplace and audience. This combination of a journalistic or public service function with a commercial one necessarily drives photojournalists to produce work that can perform effectively on both levels. At its best, this generates work that is socially relevant while also generating audiences, and produces a financial return for the photographer that allows them to continue their practice.

What is a photojournalist?

Another feature of this contemporary economy of images is the increasing difficulty of maintaining clear boundaries between the various practices that make it up. Just as the lines begin to blur between editor and viewer, consumer and producer, professional and amateur, the definition of photojournalism itself is also drawn into question. In particular, the differences between photojournalist and documentary photographer can be so indistinct that many practitioners no longer attempt to choose between these titles. But for our purposes, a distinction is necessary, if only to delineate the scope of this book in a manageable way.

The photojournalism then, is one who makes work intended for a public audience either through editorial publication - primarily in magazines or online - or for non-governmental organizations (NGOs). These formats allow for extended photo series or essays'. This is, for the most part, what is meant by the use of the term 'photojournalism' in this book.1 Newspapers, in contrast, tend not to rely on series but on isolated single images to illustrate their stories, and newspaper wire services such as Reuters, the Associated Press (AP) and Agence France Presse (AFP) until relatively recently have typically also concentrated on the single image, largely in order to downplay the individuality of their photographers in a desire to promote a sense of objective reality (however contested this concept may be).2 These might be more accurately defined as news photographers as opposed to photojournalists, although the technological advances of the digital age have allowed these agencies to begin to distribute longer-form stories that could be considered as photojournalism by our definition. That is not to say that photojournalists do not also cover fast-moving news events nor that their images are never published individually, but that their prime concern is a deeper kind of interaction with the situation, often involving repeated visits over substantial periods of time. Defining documentary photography in relation to photojournalism tends to be a question of both subject matter and form. Longer-term projects intended primarily for exhibition in galleries or publication in books can be features of both, but the documentary photographer usually favours stories that engage with accounts of the state of things and underlying sociopolitical conditions, as opposed to photojournalism's focus on the topical events that constitute news and current affairs.

Clearly there is considerable overlap and blurring of the boundaries between all of these definitions, with individual practitioners at various times - even within a single day - working in ways that could be described using any of them. In this book we discuss some single news images and also work that falls into the category of documentary and even art (a range of distinctions that is further explored inChapter 7). But clarifying some of the differences and relationships between them is nonetheless useful, and the book is centred around the term photojournalism in particular because it marks an important and identifiable form while also encapsulating a range of related practices within the increasingly dynamic network that constitutes the wider visual media environment.

Roles and identities

Having put forward a definition of photojournalism itself, we can now turn to some of the other sorts of labels and roles that photojournalists have used more specifically to characterize their particular objectives. Looking at these labels can help in identifying some of the most important critical questions surrounding photojournalism, and the ones with which we are most concerned in this book. Identities that are habitually claimed by photojournalists, such as 'witness' or 'storyteller', sometimes reflect deeply held convictions on the one hand and unquestioned assumptions on the other. In both cases, this makes them worth studying in order to better understand what photojournalism is for, how it is perceived and what makes it a unique mode of address. The following is a brief list of these stereotypical labels or identities, along with an outline of each of their implications, by way of an introduction to the scope of this book's concerns (as opposed to an outline of the book's chapters themselves, which can be found in the section titled 'Using This Book'). These categories are employed here as heuristic devices to help explore potential positions - they are meant to be ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Preface: Using This Book

- 1 What Is Photojournalism?

- 2 History and Development of Photojournalism

- 3 The Single Image and the Photostory

- 4 Photojournalism Today

- 5 Power and Representation

- 6 Ethics

- 7 Aesthetics

- 8 A Network of Trusted Witnesses

- Glossary of Terms

- Notes

- Selected Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Understanding Photojournalism by Jennifer Good,Paul Lowe in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Media & Communications Industry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.