eBook - ePub

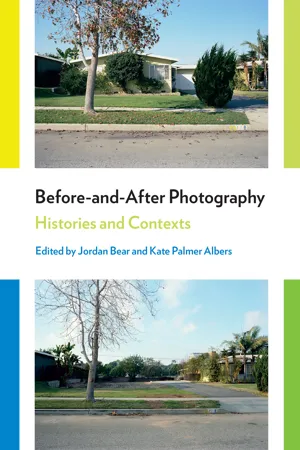

Before-and-After Photography

Histories and Contexts

- 236 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Before-and-After Photography

Histories and Contexts

About this book

The before-and-after trope in photography has long paired images to represent change: whether affirmatively, as in the results of makeovers, social reforms or medical interventions, or negatively, in the destruction of the environment by the impacts of war or natural disasters. This interdisciplinary, multi-authored volume examines the central but almost unspoken position of before-and-after photography found in a wide range of contexts from the 19th century through to the present. Packed with case studies that explore the conceptual implications of these images, the book's rich language of evidence, documentation and persuasion present both historical material and the work of practicing photographers who have deployed – and challenged – the conventions of the before-and-after pairing. Touching on issues including sexuality, race, environmental change and criminality, Before-and-After Photography examines major topics of current debate in the critique of photography in an accessible way to allow students and scholars to explore the rich conceptual issues around photography's relationship with time andimagination.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Before-and-After Photography by Jordan Bear, Kate Palmer Albers, Jordan Bear,Kate Palmer Albers in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & History of Contemporary Art. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

ArtSubtopic

History of Contemporary Art1 PHOTOGRAPHY’S TIME ZONES

KATE PALMER ALBERS AND JORDAN BEAR

Among the most significant orthodoxies in the recent historiography of photography is a shared conviction that a single, authoritative account of the medium is both impossible and undesirable. A tenet of much of the most innovative scholarship since the 1970s, this commitment to a plurality of histories is summed up in the scholar John Tagg’s haunting disavowal: “Photography as such has no identity...its history has no unity. It is a flickering across a field of institutional spaces. It is this field we must study, not photography itself.”1 Tagg’s renunciation may be most poignant to the artists, scholars, and curators who have operated from within the institutions of art, laboring to build a respectable institutional home for the medium, often by elevating the aesthetic accomplishments of individuals. The abandonment of a master narrative is, as Geoffrey Batchen argues, “a particular conception of photography that is now central to Anglo-American postmodern thinking in general.”2 One of the chief effects of this rejection of facile unity, at least in scholarship, has been an expansion beyond the predominantly art historical framework that preoccupied at least the first three-quarters of the twentieth century, toward a discourse that includes a plurality of disciplinary perspectives on “the photographic.”

The multiplicity of photography’s histories is no longer a mere aspiration; it is now a premise that underwrites scholarly examination of an extraordinary range of photographic “flickering.” Bibliometric studies attest to the diversity of fields in which the study of photography has been enlisted.3 But even as the impact of this diversity is demonstrated, it is impeded by the continued disciplinary insularity of the academic landscape, which is still dotted by specialized and idiosyncratic silos. And precisely because of photography’s lack of identity outside of specific discursive and institutional contexts, the art historian, the climatologist, and the sociologist appear to have no common idiom for discussing their photographic researches. We do not attempt to create such a universal language with this volume. Our aim is neither to homogenize photography’s role in distinct contexts nor to point to some “immanent” features of the photographic medium through which unities may be drawn. We do, however, propose that there are some bases from which comparative histories of photography can be initiated.

As such, we focus on before-and-after photographs as a strategy so commonplace that virtually every disparate photographic discourse has enlisted it. We identify before-and-after photography as a device that both inscribes and interrogates the conventions of cause and effect, development and degeneration, and referent and representation. It has a rich history beginning in the nineteenth century, but also begs philosophical and conceptual questions that are now at the heart of contemporary debate. The particular areas where before-and-after photos are most central are notably timely ones: the visual impact of climate change, medical therapies, war, and the politics of race and assimilation. Yet, the early instances of before-and-after photography are not simply naïve foils to more overtly critical recent interventions. The promiscuity of the mechanism is not readily mapped onto a linear narrative, as the knowingly critical carte de visite pairs from the 1860s and the oblivious realism of contemporary “makeovers” jointly attest.

At the same time, focusing on this endemic practice preserves the fundamental variety of these histories. The particular deployments of this device in any given history reveal some of its users’ most critical assumptions about photography, or, conversely, their queries about its limits. The omnipresence of before-and-after photographs in a wide range of disciplines allows for a unique approach: to use a specific photographic device to place into dialogue the diversity of research on photography that is taking place in relatively isolated ways in so many areas of scholarship. Doing so, however, demands that we first explain our terms: What distinguishes before-and-after photography from its apparently close relatives, particularly the “then-and-now” pair, and the series? Establishing what is unique brings into focus two broader conceptual dimensions key to the history of photography at large.

Before-and-after photographs, we propose, often obtain their special identity from the ways in which the photographs relate both to one another, and, most intriguingly, to a third, generally unseen, event. This missing pivot is the implicit source of the development whose outer markers are imaged in the before-and-after pair. The perceived gap between these images employs—and troubles—two kinds of photographic conventions, both of whose continual interrogation have been central features of the historiography of the medium. First, these pairs underline the widely held temporal expectations for photographs and their capacity to render duration visible and legible, to serve as an empirically reliable representation of the ordering force of causation in the natural world. Second, the pairs, while fundamentally photographic, derive their power from a necessary reliance on the viewer’s imagination of what happens outside of the photographic frame. As such, before-and-after pairs carry an implicit critique of common assumptions about photographic indexicality, for the referent that can be said to have caused the photograph to exist leaves no direct trace in the representation itself. Before-and-after photographs foreground and interrogate with special acuity the temporal and referential dimensions by which other modes of photography are silently governed.

No major philosophical account of time was more indebted to the temporal relations among multiple photographic images than the one advanced by Henri Bergson just after the turn of the twentieth century. Bergson’s conception of time was in part a recoil from the serial photographs of movement pioneered by Étienne-Jules Marey and Eadweard Muybridge. In these chronophotographs, Bergson located a broader symptom of modernity’s inability to conceive of duration. As the historian Anson Rabinbach has put it, “Marey thus confirmed Bergson’s diagnosis of the crisis of all perceptual systems: objective time was infinitely divisible; moments of experience were organized spatially, that is, the reduction of quality to quantity.”4 The arrogance of the supposed “objectivity” of these snapshots had, for Bergson, deleterious effects upon human perception, for isolating these moments changes their nature. Although never mentioned by name, Bergson must have Marey in mind when he claims that

along the whole of this movement we can imagine possible stoppages: these are what we call positions of the moving body, or the points by which it passes. But with these positions, even with an infinite number of them, we shall never make movement. They are not parts of movement, they are so many stoppages of it, they are, one might say, only supposed stopping places. The moving body is never really in any of the points; the most we can say is that it passes through them.5

Accordingly, one recent account has gone so far as to assert that “photography is the perfect anti-Bergsonian technology because it records through segmentation.”6

Before-and-after pairs, however, dispense with the pretence of representing intervals altogether. Indeed, it is precisely these “stoppages” or “positions” that they eschew. They literalize what Bergson claims is the ultimate shortcoming of photographic representation in particular and materialistic science generally: “As to what happens in the interval between the moments, science is no more concerned with that than are our common intelligence, our senses and our language: it does not bear on the interval, but only on the extremities.”7 Before-and-after pairs refuse to represent these intervals, except as absent events that have escaped representation, thus pointing to the limitations of their own medium. They invoke those dimensions of the world which escape both the camera and the mind.

Rejecting the possibility of depicting a comprehensive, step-by-step unfolding of an event in time was at the center of Bergson’s intellectual project. In his Creative Evolution (1907), Bergson sought to dispel mechanistic versions of evolution, like Herbert Spencer’s notion of “survival of the fittest,” that produced dubious social and ethical outcomes. As Jimena Canales has noted, Bergson “questioned Spencer’s mechanistic evolution by first questioning the basic techniques of representation used in the sciences by everyone ranging from evolutionary scientists to astronomers.”8

Evolutionary models came, over the course of the second half of the nineteenth century, to inform, if not dominate, virtually all areas of Western thought. And so Bergson’s unraveling of its representational—and conceptual—conventions guides us to some of the other most compelling dimensions of before-and-after photographs. Photographic representations are very often arguments about progress and decay, similarity and difference. These arguments, which can be submerged into the “neutrality” of the medium in single photographs, are made palpable by the before-and-after pair.

Such pairs are explicitly concerned with the idea of change, but from their earliest uses these photographs can evince skepticism. In pairs whose constituent photos are ostensibly separated by a long duration, we see telltale evidence of a much shorter period, such that the interval between the two images is not months or years, but just long enough for a costume change to take place. In the infamous case of the social reformer Dr. Thomas Barnardo, before-and-after cartes de visite were produced to show the transformation of a street urchin into a proper little bourgeois gentleman.9 When the photographs were revealed to have been staged in the studio—and almost certainly made during the same sitting—the public was predictably indignant. Barnardo’s charity suffered a collapse in donations, a plunge generally attributed to outrage over his offense against photographic “authenticity.” But Barnardo had violated a very particular set of expectations about paired photographs: that they were well suited to measure progress attest to an affirmative of middle-class altruism. It was the temporal deception, as much as the clumsy studio props and tattered garments, that was at issue. The legibility of a presumed relationship in time was the backbone of a system of visual representation underwriting some of society’s most fundamental beliefs about itself.

These beliefs are registered not only in the temporal realm but also in the photographic image’s fraught referential relationship to the “real” object or event it depicts. This linkage has always been a cornerstone of photographic theory, oscillating across an evidentiary spectrum, from a positivist view of a transparent connection between the two to a thorough skepticism of the medium’s ability to tell any kind of truth. Before-and-after pairs disrupt each end of this belief spectrum, paradoxically, by embracing both of them. They depend as much upon the evidentiary aspects of visible temporal bookends as they do upon acknowledging that the more powerful way of articulating the central event is to leave it unseen. The before-and-after pair relies on the imaginative participation of the viewer, thereby diverting attention from the “proof” of the photographs toward the viewers’ own—necessarily subjective—interpretation.

It is the philosopher and semiotician Charles Sanders Peirce whose propositions about indexicality are most often invoked in photographic theory. Peirce’s expression of the relationship between a photographic image or object, and the real world referent to which it points, is often only narrowly interpreted, but its capacious view of indexicality is particularly worth detailing in the context of the limits and possibilities of the before-and-after pair. Certainly the most common mode of conceptualizing this relationship is what Peirce describes as a responsive physical relationship. This is an attribute that makes photographs powerfully seductive in the first place: as objects made real, literally come into being, by direct physical response to an existing yet external body. In our most common photographic experience, there is a visible and conceptual alignment between what we see in the photograph and what we can imagine more or less having been “seen” by the photographer.

Peirce also established the idea of an index as a type of pointing: both photographs and spoken language can demonstratively say, look at “this” or “that.” In this mode, an index could be anything that focuses attention, including, for example, a loud noise or a startling event. Yet, a viewer’s attention is directed, and focused, by more than just a pointing index finger. And, often, the more interesting photographs document or suggest a stranger relationship than the most straightforward configuration of indexicality suggests. Most intriguingly for the present discussion, Peirce writes that an index “marks the junction between two portions of experience.”10 He elaborates, “Some indices are more or less detailed directions from what the hearer is to do in order to place himself in direct experiential or other connection with the thing meant.”

The curious disruption of the visibly seen event that marks the heart of the before-and-after pair seems quite suited to this last configuration. If, in these pairs, “the thing meant” is an imaginative understanding of an event we cannot witness, the before-and-after pair marks with special insights that “junction between two portions of experience.” Further, we could observe that the two portions of experience that interest Peirce might be defined in different ways: (1) the more literal visual portions—the experience before and the experience after—or (2) the seen and the imagined.

More recently, David Green and Joanna Lowry have suggested that the very process of making a photograph is “a kind of performative gesture which points to an event in the world.”11 While the authors’ interest is in a kind of captured invisibility within a single frame, the notion of using photography to point at something that can’t be seen is a central function of the before-and-after pair. These pairs, then, function in multiply indexical ways and themselves point to a more expansive framework of interpreting how we understand our perceptions as they emerge from various photographic cues.

Perhaps not surprisingly, many of the more conceptually charged interventions into the before-and-after device turn precisely on these common expectations. And, as the following essays attest, any disruption of the viewer’s assumptions regarding before-and-after pairs is reason for pause. In the late twentieth century, amid broader shifts in thinking about the relationship between photography and a truthful record, we see a burgeoning of artistic interest in deploying this device in order to subvert an expected temporal or visible change.

This volume ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- List of Contributors

- 1 Photography's Time Zones

- PART ONE MEDICAL RESTORATIONS AND ENHANCEMENTS

- PART TWO LANDSCAPE AND THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT

- PART THREE NATURAL AND UNNATURAL DISASTERS

- PART FOUR SOCIAL "IMPROVEMENTS": ASSIMILATION AND REFORM

- PART FIVE FROM TWO TO THREE: BEFORE-AND-AFTER TIME, COMPLICATED

- Afterword

- Index