eBook - ePub

The Guidebook for Patient Counseling

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Guidebook for Patient Counseling

About this book

This book presents the skills pharmacists need to step out from behind the counter and counsel patients. It is designed to assist practitioners to fully comply with the professional and legal requirements for patient counseling.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Guidebook for Patient Counseling by Tracey S. Hunter,Harvey M. Rappaport,Joseph F. Roy,Kelly S. Straker in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Mental Health in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

The Pharmacist-Patient Relationship

The willingness or desire to counsel and advise patients about their medication needs may be rooted in the pharmacist-patient relationship. An understanding of the nature of this relationship can be instrumental in motivating pharmacists to use their patient counseling skills.

But what is the pharmacist-patient relationship? Ethical and professional considerations suggest that it be described as an effective interaction between two parties having shared responsibility for health-care outcomes. Thus, the pharmacist would be expected to fill the medication needs of the patient and provide a full measure of professional ability as a health-care practitioner, while the patient would respond with full medication compliance. This view of the pharmacist-patient relationship appears consistent with the current practice philosophy known as “pharmaceutical care.”

Pharmaceutical care has been defined as “the responsible provision of drug therapy for the purpose of achieving definite outcomes that improve the patient’s quality of life.” The possible outcomes include: (1) cure a disease, (2) eliminate or reduce the patient’s symptoms, (3) arrest or slow a disease’s progress, and (4) prevent a disease or symptoms of a disease. Thus, under pharmaceutical care as well, the pharmacist provides pharmaceutical expertise in exchange for a patient’s medication compliance.

The pharmacist-patient relationship, under pharmaceutical care, is fundamentally grounded in the concept of the professional covenant. A covenant is a mutual exchange of benefits in which the patient grants authority and trust to the provider (pharmacist) and the provider promises competence and commitment to the patient. The covenant relies on mutual trust, respect, and application of ethical values. Professionals add to this commitment, a large body of knowledge and acceptance of responsibility for their patient’s welfare.

The proposed Code of Ethics for pharmacists being drafted by the American Pharmaceutical Association suggests that the ethical conduct of pharmacists should be guided by a “covenantal relationship between the patient and the pharmacist.” It further states that:

Considering the patient-pharmacist relationship as a covenant means that each pharmacist has moral obligations in response to the gift of trust received from society. In return for this gift, the pharmacist promises to help individuals achieve optimum benefit from their medications, to be committed to their welfare, and to maintain their trust.

However, many practitioners believe that they may be bound by a different pharmacist-patient relationship, that of the professional contract. This viewpoint suggests that, in addition to the professional characteristics, there is a mutually acceptable exchange of rights and obligations between practitioner (pharmacist) and patient. The heart of this relationship is informed consent rather than trust. Supporters argue that a contractual understanding of a therapeutic relationship encourages full respect for the dignity of the patient and full medication compliance. Yet both parties may tend to guard their own interests. Thus, the contract also provides for legal enforcement of the agreed-upon terms.

An interesting variation in the nature of the pharmacist-patient relationship is the idea that there is a contract within every professional covenant. Supporters of this view suggest that the professional pharmacist can fulfill all patient care commitments without neglecting one’s own business interests. The stability of the business may even become the foundation for sustaining the pharmacist’s ability to practice pharmaceutical care.

Is the professional covenant, professional contract, or some variation the most realistic assessment of the pharmacist-patient relationship? Which is most likely to act as a motivating force in encouraging pharmacists to counsel patients under actual practice conditions? Perhaps a close look at the ways in which pharmacists perceive their own pharmacist-patient relationships can shed some light.

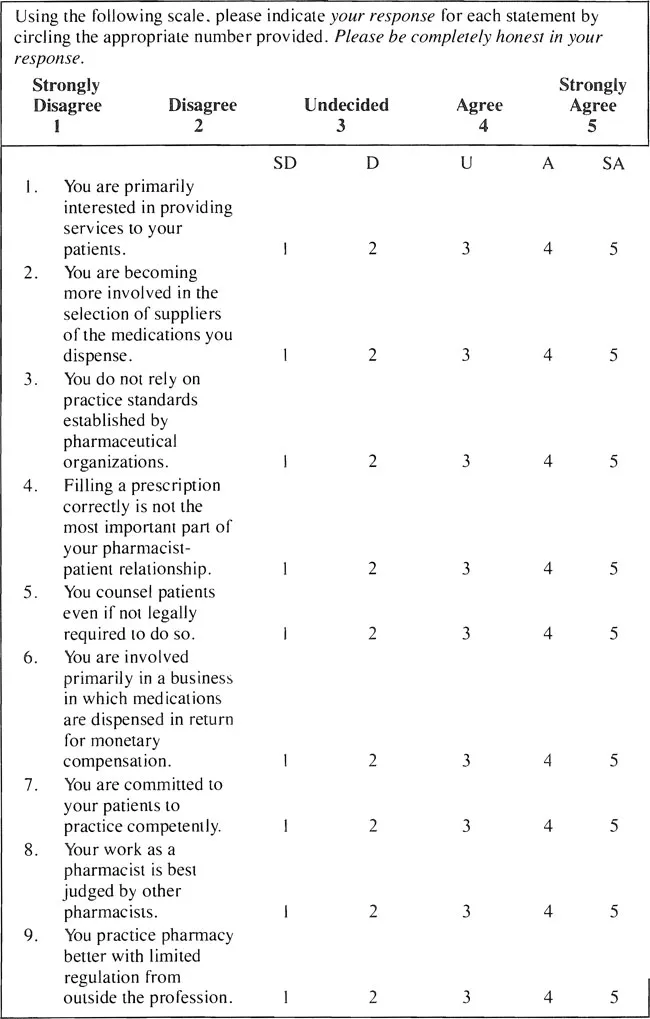

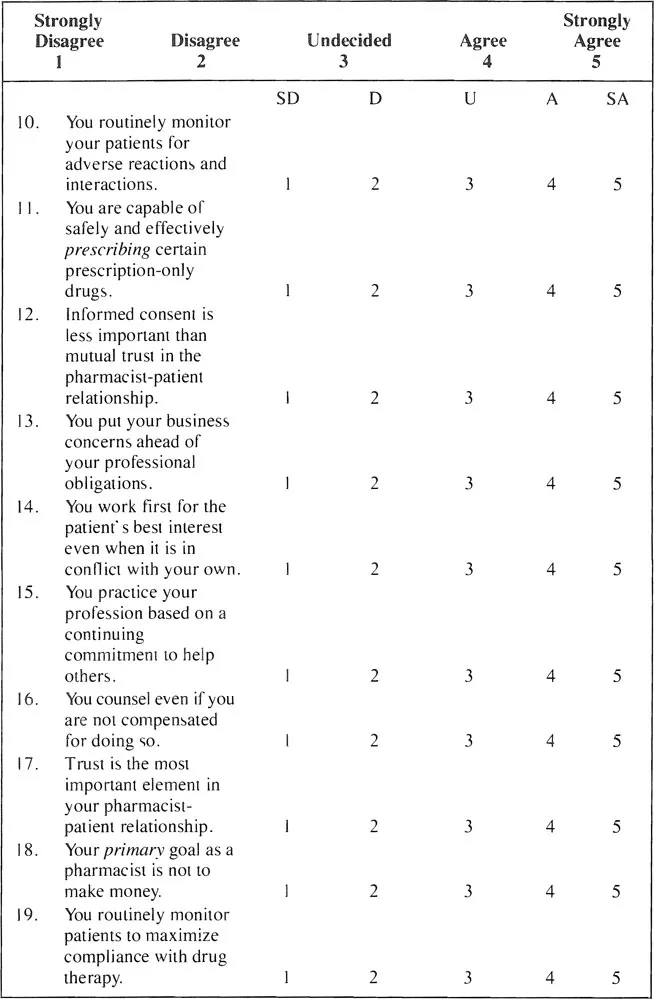

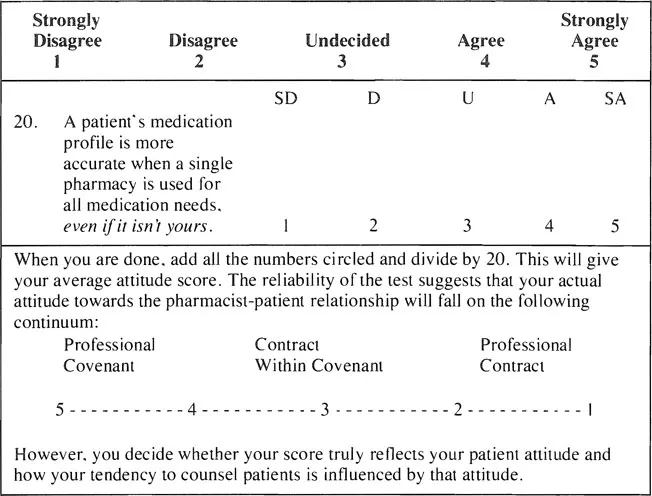

Accordingly, we have developed a test to assess a pharmacist’s attitude towards the pharmacist-patient relationship. “Attitude” signifies the way one sees relationships in the environment based upon past experiences. What attitude do you have towards your patients in your practice setting? Depending on the nature of your relations with your patients, this test could be used to measure that attitude (see Figure 1.1).

CHAPTER 2

State and Federal Statutes and Regulations Concerning Patient Counseling

OBRA’90 is an acronym for the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1990. As is evident from the term “Budget,” this Act consists of fiscal, budgetary and related provisions. “Omnibus” indicates that it is a mosaic of legislation, affecting many areas of federal law. Although it would be more proper to refer to the specific part of the Act which concerns pharmacists and patient counseling, the acronym for the entire Act has become synonymous with this part and for ease of understanding, will be so designated in this chapter.

OBRA’90 consists of three major sections: pharmaceutical pricing and manufacturer rebate provisions; a drug use review program (DUR), of which patient counseling is a part; and demonstration projects. The pricing/rebate component went into effect shortly after enactment while the others were not to become effective until January 1, 1993.

The primary effect of the DUR program is to improve the quality of care received by Medicaid beneficiaries by reducing their exposure to hazards resulting from the inappropriate prescribing, dispensing and use of prescription drugs. According to the Health Care and Financing Administration (HCFA), up to 30 percent of the prescriptions for several potential problem drugs were inappropriate.

The DUR program requirement had its genesis in the ill-fated Medicare Catastrophic Coverage Act of 1988, which contained the first provision for utilization review and patient counseling. The Act was repealed before becoming effective.

Subsequently, in 1990, two separate Senate bills were introduced but never passed. One was the Pharmaceutical Access and Prudent Purchasing Act (PAPPA), which would have established a national formulary under the auspices of a DUR Board. The other was the Patient Benefit Restoration Act (PBRA) which permitted an open formulary but also contained a DUR/prior approval system. The PBRA was intended to restore some of the patient benefits lost by the repeal of the Medicare Catastrophic Coverage Act.

Because DUR programs are believed to improve the quality of pharmaceutical care while saving money, one was incorporated into OBRA’90. The Congressional Budget Office has estimated that annual combined federal and state savings will range from $10 to 40 million. As a result of more efficient and exact utilization of pharmaceutical therapy, a decrease in the number of prescriptions written and dispensed is expected.

Once OBRA’90 became law, its various provisions were merged into corresponding portions of the United States Code. The DUR program, with its patient counseling component, was added to Title XIX of the Social Security Act. This Title authorizes grants to those states electing to provide outpatient prescription drug coverage to needy individuals under their Medicaid plans. It is administered by HCFA, which published interim final regulations in the Federal Register, Vol. 57, No. 212 (November 2, 1992).

The DUR program is intended to improve the quality of pharmaceutical care by ensuring that prescriptions are appropriate, medically necessary and not likely to cause adverse medical results. “Adverse medical resulf” means a clinically significant undesirable effect, experienced by a patient, due to a course of drug therapy. “Appropriate and medically necessary,” is defined as drug prescribing and dispensing in conformity with the predetermined standards developed or obtained by each state.

In order to qualify for federal financial participation, each electing state was to have its DUR program in operation by January 1, 1993. The program must consist of four components: prospective drug use review; retrospective drug use review; the application of predetermined standards; and an educational strategy.

Prospective DUR consists of a point-of-sale/distribution review of drug therapy before each prescription is filled or delivered, the maintenance of patient profiles and patient counseling. The review must include screening to identify potential drug therapy problems due to therapeutic duplication, drug-disease contraindication, adverse drug-drug interaction (including serious interactions with nonprescription or over-the-counter drugs), incorrect drug dosage, incorrect duration of drug treatment, drug-allergy interaction and clinical abuse/misuse.

These problems are defined as follows:

1. Therapeutic duplication – the prescribing and dispensing of two or more drugs from the same therapeutic class such that the combined daily dose puts the recipient at risk of an adverse medical result or incurs additional program costs without therapeutic benefit

2. Drug-disease contraindication – the potential for, or the occurrence of, an undesirable alteration of the therapeutic effect of a given prescription because of the presence, in the patient for whom it is prescribed, of a disease condition or the potential for, or the occurrence of, an adverse effect of the drug on the patient’s disease condition

3. Adverse drug-drug interaction—the potential for, or occurrence of, an adverse medical effect as a result of the recipient using two or more drugs together

4. Incorrect drug dosage — the dosage that lies outside the daily dosage range specified in the predetermined standards as necessary to achieve therapeutic benefit (Dosage range is the strength multiplied by the quantity dispensed divided by the day’s supply.)

5. Incorrect duration of drug treatment—the number of days the prescribed therapy exceeds or falls short of the recommendations contained in the predetermined standards

6. Drug-allergy interaction — the significant potential for, or the occurrence of, an allergic reaction as a result of drug therapy

7. Clinical abuse/misuse — the occurrence of situations referred to in the definitions of abuse, gross overuse, overutilization, underutilization, incorrect dosage and incorrect duration

a) Abuse: no definition provided in this section

b) Gross overuse: repetitive overutilization without therapeutic benefit

c) Overutilization: use of a drug in quantities or for durations that put the recipient at risk of an adverse medical result

d) Underutilization: a drug is used by a recipient in insufficient quantity to achieve a desired therapeutic goal

e) Incorrect dosage: refer to No. 4, above

f) Incorrect duration: refer to No. 5, above

In addition to the screening provision of the prospective DUR program, the pharmacist must make a reasonable effort to obtain, record and maintain patient profiles of each Medicaid recipient. (See Chapter 7.) At a minimum, the profile must contain:

1. The name, address, telephone number and date of birth (or age) and gender of the patient

2. Individual medical history, where significant, including disease state(s), known allergies and drug reactions, and a comprehensive list of medications and relevant devices

3. Pharmacist comments relevant to the individual’s drug therapy

HCFA suggests that the information developed from the patient profile be used to assist the pharmacist in the screening portion of the prospective DUR process. Further, where appropriate, the pharmacist might consult a physician to obtain additional details.

The final phase of the prospective DUR process entails counseling of the patient. The pharmacist must offer to counsel the patient or caregiver about the prescription. At a minimum, the counseling must encompass an offer to discuss with the patient or caregiver certain matters that the pharmacist deems significant. The discussion must be in person where practicable; otherwise, by toll-free telephone service. It should include (in addition to those matters already deemed significant) at least the following:

1. The name and description of the medication

2. The dosage form, dosage, route of administration and use by the patient

3. Special directions and precautions for preparation, administration and us...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Chapter 1. The Pharmacist-Patient Relationship

- Chapter 2. State and Federal Statutes and Regulations Concerning Patient Counseling

- Chapter 3. Liability and Other Legal Issues Affecting Patient Counseling

- Chapter 4. Overview of Communication Skills

- Chapter 5. The Counseling Environment and Design

- Chapter 6. The Use of Pharmacy Technicians in Patient Counseling

- Chapter 7. Patient Medication Profile Development

- Chapter 8. The Prescription Label

- Chapter 9. Counseling the Patient

- Chapter 10. Applying Patient Counseling to the Practice Setting (Scenarios)

- Index