Setting the Scene

Writing 80 years before the excavations at Howick, Francis Buckley anticipated the occurrence of Mesolithic remains there after his discovery of narrow-blade Mesolithic flints at Budle Crags near Bamburgh, Brada Crags near Spindlestone and Chester Crags near Outchester (Buckley 1922).

“It is likely that the coastland crags south of Craster have some relics of the Tardenois fishermen; and under favourable circumstances such relics should in time be found.”

(Francis Buckley 1922, 323).

Buckley likened the flint industry from these sites to the ‘Tardenois’ industry recognised at the time in northern France and Belgium. Today these Northumberland flints are no longer seen as being a direct extension of the Tardenois industry, but rather fit into the Later Mesolithic micro-triangle techno-complex recognised to exist across the British Isles and related to traditions that extended over much of North-West Europe at this time (see Jacobi 1976). The drawings published by Buckley include scalene triangle and crescent microliths, together with scrapers typical of this tradition, and these are directly analogous to those found at Howick. His anticipation of the Howick site, which lies 3km south of Craster, demonstrates the regard with which the area was considered, even then, for hosting Mesolithic remains. This study presents the results of the investigation of an early 8th millennium cal BC Mesolithic hut site that was found eroding out of a cliff that overlooks the Howick Burn estuary in midNorthumberland (Fig. 1.1).

Although significant work had been undertaken along the Northumberland coast by earlier researchers (see Young 2000a for review) who collected Mesolithic flints from erosion scars (e.g. Davies 1983, Young 2000a), burnt field surfaces (e.g. Buckley 1922), old sand dunes (e.g. Raistrick 1934) and ploughed field surfaces (e.g. Weyman 1984), very little was known concerning the dating of this material. Indeed prior to the work at Howick there were no published radiocarbon dated Mesolithic sites, no excavated Mesolithic structures and no sequence for Mesolithic flint assemblages in Northumberland. The opportunity provided by the Howick site for establishing firm radiocarbon dates for the Mesolithic, and for dating particular lithic types from undisturbed contexts, meant the beginnings of a chronological framework could be developed.

Against this backdrop of chronological uncertainty there was very little known about Mesolithic habitation sites. The only exceptions to this are the rock shelter sites that have been investigated along the Fell Sandstone escarpments at Goatscrag (Burgess 1972) (Fig. 1.2), Corby’s Crag (Beckensall 1976) and most recently at Salter’s Nick (John Davies pers. comm.). Goatscrag and Corby’s Crag produced only small quantities of lithic material together with some traces of structural features, including drip gullies, post holes, pits and hearth pits for what are thought to have been temporary structures (e.g. Burgess 1972). However, the discovery of Bronze Age cremation burials in inverted cinerary urns indicates that later activity took place in these shelters and it is possible that this later phase of activity accounts for the pits, gullies, post holes and fire pits. Until such features are directly dated, their Mesolithic attribution will remain contentious. Interestingly though, four carvings of quadrupeds, that most likely represent deer (Fig. 1.3), have been discovered on one of the vertical walls within rock shelter B at Goatscrag (van Hoek and Smith 1988). Although these images cannot be dated directly, the use of figurative art is a style common to hunter-gatherer groups, whereas the Neolithic–Early Bronze Age rock art of the region is purely non-figurative (see Beckensall 2001; Waddington 1999a, 108; Waddington 1998). This possible survival of Mesolithic art opens up an interesting avenue for future research, particularly in the light of the recent discoveries of early hunter-gatherer art in caves at Creswell Crags (Ripoll et al. 2004) and Cheddar Gorge (Mullan and Wilson 2004).

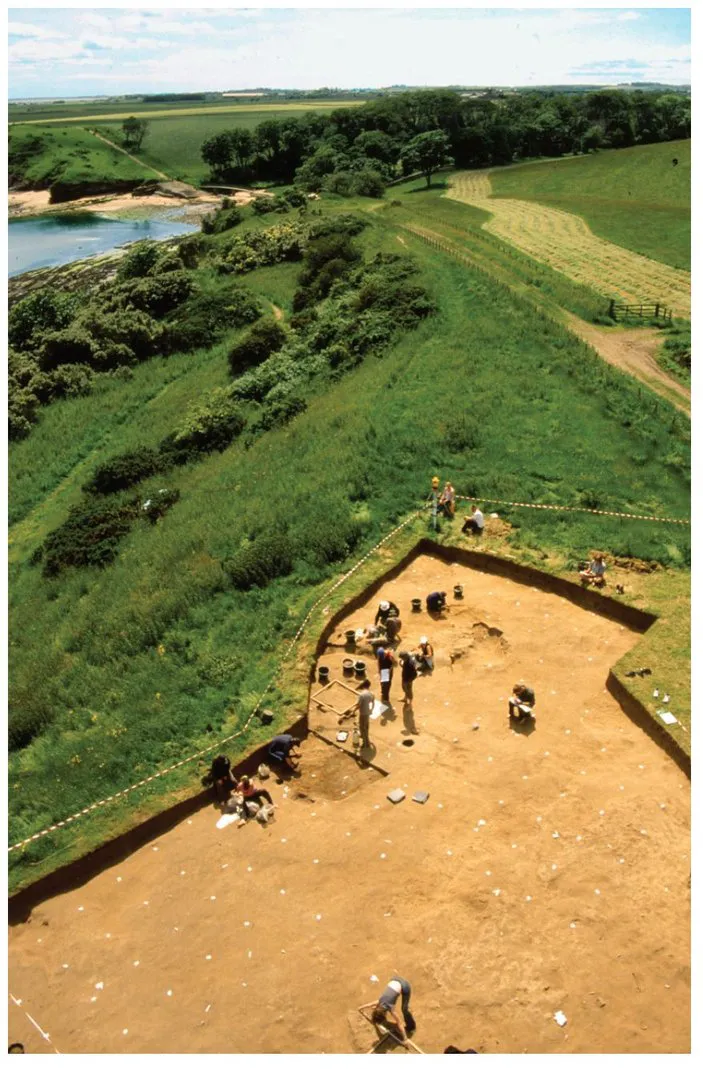

Figure 1.1. View over the Howick excavations looking south with the Howick Burn estuary in the background. The hut site is located towards the top of the trench along its left edge.

Figure 1.2. View of the Goatscrag rock shelter site B.

Although only limited work has taken place to date, the potential for Mesolithic research in Northumberland and the Borders, on the coast, along river valleys and in the uplands, is considerable, particularly given the fact that there are so many opportunities for acquiring environmental data from sediment sequences that extend from the Late Glacial onwards. The study presented here will contribute new detail to the study of early hunter-gatherer-fisher groups in the region while providing a platform for a renewed research impetus. However, beyond the regional research context, there have been few wellresourced excavations of Mesolithic sites in the British Isles as a whole, with study of the period dominated by a handful of key sites, notably Star Carr (Clark 1971), Thatcham (Wymer 1962), Mount Sandel (Woodman 1985), Morton, (Coles 1971; 1983), Oronsay (Mellars 1987), the Southern Hebrides Sites (Mithen 2000), Kinloch (Wickham-Jones 1990) and the Obanian sites (e.g. Bonsall 1996) amongst a few others. In the light of the current research climate the Howick project has been fortunate to enjoy the level of support necessary to undertake detailed and full recording of a relatively intact habitation site. Given the wealth of information that it has been able to produce it is hoped that other sites of this period will benefit from well-resourced study in the future, in order to help unlock some of the questions relating to the early settlement of the British Isles.

Figure 1.3. The ‘deer’ carvings on the vertical wall inside Goatscrag rock shelter site B.

Scope of the Volume

This volume provides a full report of the fieldwork programme directed at understanding the Mesolithic remains at Howick together with analysis and interpretation of the data in their wider North Sea context. The Bronze Age cist cemetery discovered during the excavation of the Mesolithic hut is not included in this volume but is reported separately in a journal article (Waddington et al. 2005). The volume has been structured to broadly follow the sequence of fieldwork undertaken at the site, followed by the analytical chapters and then the wider discussion. As most of the analyses proved highly revealing, and in some cases incorporated innovative and groundbreaking work (e.g. Chapter 6), it was considered important to present this work as a series of chapters in their own right rather than relegating them to appendices. As a result no appendices are included in this volume. The chipped stone recovered from the excavation is discussed in Chapter 7, starting with an assemblage description, followed by metrical, temporal and spatial analysis and concluding with an overview. Chapter 8 discusses the other lithic material produced by the excavation, while Chapter 9 presents a study of residues and use-wear on a selection of the chipped stone and other lithic material. It was decided to break the lithic work up into separate chapters for ease of navigation by the reader. A review of bevelled pebble tools and interpretation of the Howick group is provided in Chapter 14. However, discussion and interpretation of the chipped stone tool assemblage in relation to its wider chronological and geographic context is presented in Chapter 15.

A crucial point for readers to note is that all dates expressed in the text of this volume are given in calibrated years BC (i.e. calendrical dates). Although this is conventional for later prehistory it has not, in the past, been the custom for studies geared to the early Holocene. Adopting the same chronology for Mesolithic as for later sites will allow the real time difference between them to be articulated; accordingly all the 8th millennium cal BC sites in the British Isles have been calibrated using the latest curve (see Chapter 15). Another important point to make regarding the expression of chronologies in this volume is the use of age ranges given in italics, particularly in Chapters 6 and 15. These italicised date ranges refer to the mathematically modelled probabilities based on the combined radiocarbon determinations and do not indicate actual radiocarbon dates, which are always quoted in standard typeface. It is recommended that the reader consult Chapter 6 and its accompanying figure captions for further clarification.

Site Discovery

Flints were first recorded falling out of an erosion scar at Howick by John Davies (1983), an amateur archaeologist and member of the Northumberland Archaeology Group, who noted the flints as being of Mesolithic date. No further investigation of the site took place and it was largely overlooked for the next 17 years. Early in 2000 Jim Hutchinson, also a member of the Northumberland Archaeology Group, brought a handful of flints he had found at the same erosion scar and in nearby molehills to an artefacts day school organised by the then ‘Centre for Lifelong Learning’ at the University of Newcastle. The flints were shown to the author who was able to confirm that these flints were of Later Mesolithic ‘narrow-blade’ type. Subsequent to this Jim Hutchinson took the author out to the site and showed him the erosion scar and molehills. More flints were found eroding out of the section but it was noted that most of the material was coming from the soil layer below the plough zone, which, significantly, suggested that in situ remains survived on the site. This aroused a greater sense of interest and anticipation as it was known that there had been very few opportunities to excavate intact Mesolithic deposits in North-East England before. Photographs were taken and the farmer and landowner were informed. A return visit to the site was made by the author, together with Nicky Milner and Ben Johnson, to excavate a single 1m square test pit immediately behind the erosion scar to test whether subsurface archaeological deposits survived. The test pit produced a total of 51 flints and at the top of the sandy substratum an archaeological feature was identified that contained quantities of flint and charred hazelnut shell within a sandy weathered fill. This generated immense excitement as the survival of such deposits suggested that in situ Mesolithic remains did in fact survive on the site. What was more, these remains were being steadily eroded by a combination of slippage from the erosion scar and burrowing moles, and this added a sense of urgency to dealing with the site.

On the basis of this initial exploratory work, the author, Nicky Milner and Geoff Bailey, of the then ‘Department of Archaeology’ at the University of Newcastle, decided to undertake an evaluation of the site as a student training excavation. This evaluation work included a close-spaced geophysical survey around the immediate area of the site by Alan Biggins of Timescape Surveys (see Chapter 2), sediment coring around the Howick Burn by Ian Boomer from the Department of Geography, University of Newcastle, as well as the excavation of an evaluation t...