- 160 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

An accessible description of sleep and dreaming and the daily and seasonal rhythms that our bodies are subject to.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Awareness by Evie Bentley in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & History & Theory in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

States of awareness and consciousness

- Introduction

- Historical approach to consciousness within psychology

- Models of consciousness

- Summary

Introduction

This book is entitled Awareness. Why? Well, we humans have pride in our ability to be aware both of the world around us and of our inner mind. For instance, we are aware of our feelings and emotions. From the viewpoint of modern psychology there are several 'states' of awareness including sleep, dreaming, the hypnotic trance, lucid dreaming and even coma. This book focuses mainly on sleeping, dreaming and the hypnotic state, but there is on-going discussion as to the precise meanings of the terms 'consciousness' and 'awareness', and whether or not they mean the same thing. Even today psychologists are not able to agree on precise definitions. The concept of 'consciousness' has gone in and out of favour with psychologists, as we shall see.

Historical approach to consciousness within psychology

Wuiidt (1862) investigated consciousness using the now abandoned technique of introspection, training his participants to think deeply and describe their own mental images and feelings; their own thoughts really. He saw human consciousness as the fusing of external elements or stimuli, with internal elements such as personal emotions. This fusion produced what Wundt called our 'complexes of experience' which he saw as our consciousness. His explanations were based on his knowledge of chemistry: he thought of the external and internal elements of consciousness as mental atoms and the complexes of experience as molecules (for those of you who haven't done chemistry - molecules are arrangements of atoms).

James (1890) introduced the phrase 'streams of consciousness' to describe the constant internal mental 'noise' which we experience when awake. This stream was seen as the combined input from all our senses plus the resultant thoughts. James suggested that our awareness of the external world was due to this, but that we could focus that awareness in on certain aspects of the external or internal world. In other words we could channel our attention.

Introspection fell out of fashion with the advent of the behaviourists, such as Watson (1913) and Skinner (1938). Behaviourists argued that all behaviour could be explained in terms of learning theory and conditioning. For example, you learn that every time a bell is rung there will be food; eventually you salivate at the sound of the bell: you have learned a new association between a response (salivation) and a stimulus (the bell).

Behaviourists completely rejected the idea of consciousness because they felt it was a hypothetical and meaningless construct. They believed that consciousness was an epiphenomenon - a secondary effect which arises from brain activity but does not cause it. Consciousness was an unnecessary concept when explaining behaviour. Behaviourists similarly regarded concepts such as 'mind' and 'thought' as irrelevant to the scientific study of psychology. Such concepts had no use because they could not be observed directly nor measured.

At much the same time as James and then the behaviourists were working, a conflicting theory of consciousness was being devised by Freud. This has developed into the psychodynamic approach and is described in detail later on in this chapter.

One final thought about consciousness concerns the question about whether non-human animals have consciousness. We need to distinguish being aware, which an animal might be, from being conscious, which an animal might not be. Dennett has suggested a good example. When: a bee approaches a tree it is aware of the tree as an obstacle - it really could be anything that simply needs to be avoided - whereas we are aware (conscious) of the tree as a tree. The tree has meaning (an internal representation) that extends beyond mere avoidance of an obstacle.

Models of consciousness

Brain activity

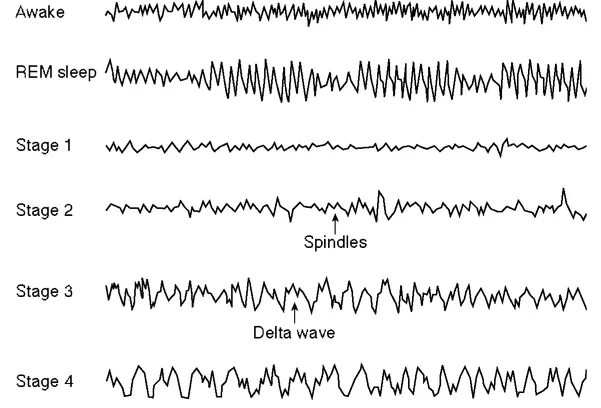

One model of consciousness is based on brain activity, using electroencephalogram (EEG) traces mainly. It is known that when a person is alert their EEG pattern is highly irregular, unsynchronised, with the spiky waves of electrical activity tightly massed together. When they are concentrating on something particular the trace changes. The waves become deeper vertically and more spread out horizontally, and they are described as slower waves. They also show a pattern called theta waves or rhythms. The same person in a relaxed and calm state has an EEG trace somewhere between the two described above. In a relaxed state their brain waves are faster than when concentrating and show an alpha wave rhythm. Figure 1.1 shows an EEG trace.

Another investigation of brain awareness or activity was done on epileptic patients who were having brain surgery to improve their condition (Penfield and Rasmussen, 1950). When operations were done on their brain the patients were awake while their skulls were opened and their brains exposed. The researchers obtained the patients' permission to stimulate areas of the brain using fine needlelike electrodes. As a result of these investigations, Penfield suggested that consciousness was located in the thalamus (part of the forebrain) and the upper part of the hindbrain.

Gazzaniga and Sperry (1967) took investigations into consciousness and brain functioning a stage further, also using patients treated surgically for epilepsy. These patients had their corpus callosuin (a

Figure 1.1 Electro-encephalogram (EEG) trace from a relaxed person with eyes closed and then open

group of nerve fibres which connect the two cerebral hemispheres) cut in a technique called split-brain procedure. These studies showed that the two halves of the brain (cerebral hemispheres) function independently of each other and have some separate functions, and also that they have some sort of independent consciousness. For example, one split-brain patient reported that when she had to decide what to wear, she sometimes found that her left hand picked out quite different clothes from those she had intended (Hayes, 1994). The suggestion is that the conscious decision was taken by the left hemisphere, but the hand reaching out was controlled by the right hemisphere (left hand controlled by right hemisphere). And of course the two hemispheres no longer communicated with each other. This may seem rather more science fiction than scientific psychology, and it does not demonstrate what or where consciousness actually is, but it does indicate that consciousness is complex and involves more than the hindbrain, and possibly involves communication between the left and right hemispheres.

Levels of consciousness

Some psychologists have suggested that there are three levels of consciousness: conscious, pre-conscious and unconscious.

The conscious mind is what we are aware of whilst awake. This is when we have self-awareness (see later section in this chapter) and so are aware of not just our environment but also our own thoughts and feelings, our sensations and responses. We also have self-control in this state and have free will to make choices and decisions. Maybe this includes our 'conscience', our ability to think morally and ethically.

The pre-conscious mind is thought of as on the fringes of the conscious mind. This is where we are not fully conscious of sensory input or thoughts, but we can focus down on them if this becomes desirable. The 'cocktail party phenomenon' (Cherry, 1953) is an example of this. At a cocktail (or other) party one might be busy with a group of people, apparently unaware of other people and what they are saying — until one's own name is spoken. At that point our attention is immediately and vividly switched to that other group. Our pre-conscious mind had been monitoring other sensory input and has switched our attention. Sometimes the pre-conscious has been called the subconscious, but this term is more commonly used with Freudian connections and using the same term here might be confusing.

The unconscious mind is a construct of Freud (1901) and comprises the hypothesised mass of deeply repressed, disturbing memories and thoughts which control our behaviour and of which, since they are so repressed, we are unaware. Freud felt that much of this repressed unconscious was sexual in origin, maybe because he was living in sexually repressive times. His ideas have been developed into modern psychodynamic theory which largely agrees with Freud's interpretation of the unconscious. One exception is the modern school based on Jung, Freud's sometime follower, who believed that there was an additional and highly significant part of the unconscious - the collective unconscious. Jung hypothesised that this held the memories and feelings of all humanity, back through time. Jung was also less than sure about the sexual basis of the unconscious. However modern psychodynamic theory still supports the general principle. that is, the existence of a controlling unconscious made up of repressed emotions and memories.

Unfortunately, as this is so strongly repressed the unconscious cannot be accessed for study except in very non-empirical ways with individuals. There are therefore no real data to support or refute the existence of the unconscious and the psychoanalytic methods of investigating the unconscious have been criticised as being heavily dependent on the analyst, that is they are very subjective and are therefore prone to bias. Freud's own research has also been criticised as his samples were both very small and very biased - a few wives of fellow professionals plus one small boy - and Freud's own notes of his interviews with his sample were written afterwards, not at the time. This means that the generalisation of Freud's interpretations to the whole population could be challenged because his samples were not typical of the normal population. Also, we now know empirically that human memory is faulty and should not be relied upon as absolute truth and so there is the chance that Freud's recollections may not have been faultless. Then there is the point that Freud himself changed his own interpretation of his interviews, though this was from one subjective opinion to another. Nevertheless, Freud's theories undoubtedly made a great contribution to the way psychologists thought about human behaviour, in particular to the consideration of hidden motives and the conception of consciousness.

States of consciousness

The most obvious states of consciousness are being awake and being asleep. Psychological research has focused on sleep. There has also been considerable interest in whether or not the hypnotic state is a special state of consciousness.

The (non-Freudian) unconscious state

Victims of various accidents and unlucky sports people (such as boxers and horse riders) may become unconscious as a result of a blow to the head. In this state there is a complete lack of awareness of the external world and, as far as can be ascertained, also of much of their internal or mental world. In this state they cannot be woken up, they do not react to any stimuli, including pain, and EEG recordings show little brain activity. It really is as though the brain has 'gone down' to use a computer analogy - neurones have shut down, the 'closed' sign has gone up. It might be that this is a protective state, but not enough is known to make any certain conclusions. A similar state is caused by some anaesthetics and other drugs, and there are anecdotal accounts of people who have appeared unconscious but have been able to report on what went on around them whilst in this state. We do not know yet whether we are dealing with one or several states with similar symptoms of being profoundly unaware.

Extreme examples of the unconscious state are when a person is in a coma. This is almost always the result of a brain injury. Coma is a sign of serious damage or disruption within the brain and if there is going to be recovery this is usually seen within a maximum of twenty weeks. People who are going to recover start to show small signs of reacting to external stimuli. Maybe their breathing-rate changes or the electrical conductivity of their skin alters or the heart-rate increases. Then they may be able to follow a moving object like a hand ill front of their eyes. They may be able to make sounds and their sleep-wake cycle may restart. What happens depends on where the brain injury is and how bad it is.

If after about tour months there is no improvement and brain scans show little neural activity in the forebrain, then the person may be said to be in a persistent vegetative state (PVS) (Jennet and Plum, 1972). This state is more likely to occur if the brain has at any time been severely short of oxygen for several minutes - irreversible damage begins after only three minutes unless the brain is very cold. People who have been trapped underwater or crushed underground can go into PVS and there is almost no chance at all of any improvement from this state of deep unconsciousness. Some people with PVS have lived for years and the occasional case reawakens completely unexpectedly, but mainly such unfortunate people slowly die. The body depends on the brain and if the brain is damaged badly enough the body cannot survive indefinitely.

Meditation

In the 1960s a single book (Tart, 1969) contained two-thirds of the research published in English on meditation. Yet now there are literally thousands of such articles, showing the explosion of interest in this state of consciousness. The reason for this is probably because of the physiological applications of meditation to health and to coping with stress. EEG traces show that meditation is closely similar to very relaxed wakefulness and also to the hypnotic state. Meditation is at the core of autogenic and similar calming techniques, and of autohypnosis. All these states depend on the person being ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- 1 States of awareness and consciousness

- 2 Bodily rhythms

- 3 Control of biorhythms

- 4 Investigating sleep: The most obvious rhythm

- 5 Theories of sleep

- 6 Theories of dreaming

- 7 Disrupting bodily rhythms

- 8 Hypnotic states

- 9 Study aids

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Index