![]()

Book III. Exchange.

Chapter I. Of Value.

§ 1. Definitions of Value in Use, Exchange Value, and Price.

It is evident that, of the two great departments of Political Economy, the production of wealth and its distribution, the consideration of Value has to do with the latter alone; and with that only so far as competition, and not usage or custom, is the distributing agency.

The use of a thing, in political economy, means its capacity to satisfy a desire, or serve a purpose. Diamonds have this capacity in a high degree, and, unless they had it, would not bear any price. Value in use, or, as Mr. De Quincey calls it, teleologic value, is the extreme limit of value in exchange. The exchange value of a thing may fall short, to any amount, of its value in use; but that it can ever exceed the value in use implies a contradiction; it supposes that persons will give, to possess a thing, more than the utmost value which they themselves put upon it, as a means of gratifying their inclinations.

The word Value, when used without adjunct, always means, in political economy, value in exchange.

Exchange value requires to be distinguished from Price. Writers have employed Price to express the value of a thing in relation to money—the quantity of money for which it will exchange. By the price of a thing, therefore, we shall henceforth understand its value in money; by the value, or exchange value of a thing, its general power of purchasing; the command which its possession gives over purchasable commodities in general. What is meant by command over commodities in general? The same thing exchanges for a greater quantity of some commodities, and for a very small quantity of others. A coat may exchange for less bread this year than last, if the harvest has been bad, but for more glass or iron, if a tax has been taken off those commodities, or an improvement made in their manufacture. Has the value of the coat, under these circumstances, fallen or risen? It is impossible to say: all that can be said is, that it has fallen in relation to one thing, and risen in respect to another. Suppose, for example, that an invention has been made in machinery, by which broadcloth could be woven at half the former cost. The effect of this would be to lower the value of a coat, and, if lowered by this cause, it would be lowered not in relation to bread only or to glass only, but to all purchasable things, except such as happened to be affected at the very time by a similar depressing cause. Those [changes] which originate in the commodities with which we compare it affect its value in relation to those commodities; but those which originate in itself affect its value in relation to all commodities.

There is such a thing as a general rise of prices. All commodities may rise in their money price. But there can not be a general rise of values. It is a contradiction in terms. A can only rise in value by exchanging for a greater quantity of B and C; in which case these must exchange for a smaller quantity of A. All things can not rise relatively to one another. If one half of the commodities in the market rise in exchange value, the very terms imply a fall of the other half; and, reciprocally, the fall implies a rise. Things which are exchanged for one another can no more all fall, or all rise, than a dozen runners can each outrun all the rest, or a hundred trees all overtop one another. A general rise or a general fall of prices is merely tantamount to an alteration in the value of money, and is a matter of complete indifference, save in so far as it affects existing contracts for receiving and paying fixed pecuniary amounts.

Before commencing the inquiry into the laws of value and price, I have one further observation to make. I must give warning, once for all, that the cases I contemplate are those in which values and prices are determined by competition alone. In so far only as they are thus determined, can they be reduced to any assignable law. The buyers must be supposed as studious to buy cheap as the sellers to sell dear.

The reader is advised to study the definitions of value given by other writers. Cairnes190 defines value as “the ratio in which commodities in open market are exchanged against each other.” F. A. Walker191 holds that “value is the power which an article confers upon its possessor, irrespective of legal authority or personal sentiments, of commanding, in exchange for itself, the labor, or the products of the labor, of others.” Carey192 says, “Value is the measure of the resistance to be overcome in obtaining those commodities or things required for our purposes—of the power of nature over man.” Value is thus, with him, the antithesis of wealth, which is (according to Carey) the power of man over nature. In this school, value is the service rendered by any one who supplies the article for the use of another. This is also Bastiat's idea,193 “le rapport de deux services échangés.” Following Bastiat, A. L. Perry194 defines value as “always and everywhere the relation of mutual purchase established between two services by their exchange.” Roscher195 explains exchange value as “the quality which makes them exchangeable against other goods.” He also makes a distinction between utility and value in use: “Utility is a quality of things themselves, in relation, it is true, to human wants. Value in use is a quality imputed to them, the result of man's thought, or his view of them. Thus, for instance, in a beleaguered city, the stores of food do not increase in utility, but their value in use does.” Levasseur196 regards value as “the relation resulting from exchange”—le rapport resultant de l'échange. Cherbuliez197 asserts that “the value of a product or of a service can be expressed only as the products or services which it obtains in exchange.… If I exchange the thing A against B, A is the value of B, B is the value of A.” Jevons198 defines value as “proportion in exchange.”

§ 2. Conditions of Value: Utility, Difficulty of Attainment, and Transferableness.

That a thing may have any value in exchange, two conditions are necessary. 1. It must be of some use; that is (as already explained), it must conduce to some purpose, satisfy some desire. No one will pay a price, or part with anything which serves some of his purposes, to obtain a thing which serves none of them. 2. But, secondly, the thing must not only have some utility, there must also be some difficulty in its attainment.

The question is one as to the conditions essential to the existence of any value. Very justly Cairnes199 adds also a third condition, “the possibility of transferring the possession of the articles which are the subject of the exchange.” For instance, a cargo of wheat at the bottom of the sea has value in use and difficulty of attainment, but it is not transferable. Jevons (following J. B. Say) maintains that “value depends entirely on utility.” If utility means the power to satisfy a desire, things which merely have utility and no difficulty of attainment could have no exchange value.200 F. A. Walker201 believes that “value depends wholly on the relation between demand and supply.” Carey202 holds that value depends merely on the cost of reproduction of the given article. Roscher203 finds that exchange value is “based on a combination of value in use with cost value.” Cherbuliez204 calls the conditions of value two, “the ability to give satisfaction, and inability of attainment without effort. The first element is subjective; it is determined wholly by the needs or desires of the parties to the exchange. The second is objective; it depends upon material considerations, which are the conditions of the existence of the thing, and upon which the needs of the persons exchanging have no influence whatever.” It is, as usual, one of Cherbuliez's clear expositions. A. L. Perry205 states that, “while value always takes its rise in the desires of men, it is never realized except through the efforts of men, and through these efforts as mutually exchanged.”

The difficulty of attainment which determines value is not always the same kind of difficulty: (1.) It sometimes consists in an absolute limitation of the supply. There are things of which it is physically impossible to increase the quantity beyond certain narrow limits. Such are those wines which can be grown only in peculiar circumstances of soil, climate, and exposure. Such also are ancient sculptures; pictures by the old masters; rare books or coins, or other articles of antiquarian curiosity. Among such may also be reckoned houses and building-ground, in a town of definite extent.

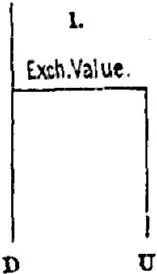

De Quincey206 has presented some ingenious diagrams to represent the operations of the two constituents of value in each of the three following cases: U represents the power of the article to satisfy some desire, and D difficulty of attainment. In the first case, exchange value is not hindered by D from going up to any height, and so it rises and falls entirely according to the force of U. D being practically infinite, the horizontal line, exchange value, is not kept down by D, but it rises just as far as U, the desires of purchasers, may carry it.

(2.) But there is another category (embracing the majority of all things that are bought and sold), in which the obstacle to attainment consists only in the labor and expense requisite to produce the commodity. Without a certain labor and expense it can not be had; but, when any one is willing to incur these, there needs be no limit to the multiplication of the product. If there were laborers enough and machinery enough, cottons, woolens, or linens might be produced by thousands of yards for every single yard now manufactured.

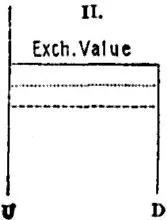

In case (2) the horizontal line, representing exchange value, follows the force of D entirely. The utility of the article is very great, but the value is only limited by the difficulty of obtaining it. So far as U is concerned, exchange value can go up a great distance, but will go no higher than the point where the article can be obtained. The dotted lines underneath the horizontal line indicate that the exchange value of articles in this class tend to fall in value.

(3.) There is a third case, intermediate between the two preceding, and rather more complex, which I shall at present merely indicate, but the importance of which in political economy is extremely great. There are commodities which can be multiplied to an indefinite extent by labor and expenditure, but not by a fixed amount of labor and expenditure. Only a limited quantity can be produced at a given cost; if more is wanted, it must be produced at a greater cost. To this class, as has been often repeated, agricultural produce belongs, and generally all the rude produce of the earth; and this peculiarity is a source of very important consequences; one of which is the necessity of a limit to population; and another, the payment of rent.

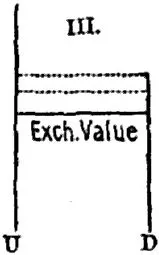

In case (3) articles like agricultural produce have a very great power to satisfy desires, and if scarce would have a high value. So far as U is concerned, here also, as in case (2), exchange value might mount upward to almost any height, but it can go no higher than D permits. In commodities of this class, affected by the law of diminishing returns, the tendency is for D to increase, and so for exchange value to rise, as indicated by the dotted lines above that of the exchange value.

§ 3. Commodities limited in Quantity by the law of Demand and Supply: General working of this Law.

These being the three classes, in one or other of which all things that are bought and sold must take their place, we shall consider them in their order. And first, of things absolutely limited in quantity, such as ancient sculptures or pictures.

Of such things it is commonly said that their value depends on their scarcity; others say that the value depends on the demand and supply. But this statement requires much explanation. The supply of a commodity is an intelligible expression: it means the quantity offered for sale; the quantity that is to be had, at a given time and place, by those who wish to purchase it. But what is meant by the demand? Not the mere desire for the commodity. A beggar may desire a diamond; but his desire, however great, will have no influence on the price. Writers have therefore given a more limited sense to demand, and have defined it, the wish to possess, combined with the power of purchasing.207 To distinguish demand in this technical sense from the demand which is synonymous with desire, they call the former effectual demand.

General supply consists in the commodities offered in exchange for other commodities; general demand likewise, if no money exists, consists in the commodities offered as purchasing power in exchange for other commodities. That is, one can not increase the demand for certain things without increasing the supply of some articles which will be received in exchange for the desired commodities. Demand is based upon the production of articles having exchange value, in its economic sense; and the measure of this demand is necessarily the quantity of commodities offered in exchange for the desired goods. General demand and supply are thus reciprocal to each other. But as soon as money, or general purchasing power, is introduced, Mr. Cairnes208 defines “demand as the desire for commodities or services, seeking its end by an offer of general purchasing power; and supply, as the desire for general purchasing power, seeking its end by an offer of specific commodities or services.” But many persons find a difficulty because they insist upon separating the idea of supply from that of demand, owing to the fact that producers seem to be a distinct class in the community, different from consumers. That they are in reality the same persons can be easily explained by the following statement: “A certain number of people, A, B, C, D, E, F, etc., are engaged in industrial occupations—A produces for B, C, D, E, F; B for A, C, D, E, F; C for A, B, D, E, F, and so on. In each case the producer and the consumers are distinct, and hence, by a very natural fallacy, it is concluded that the whole body of consumers is distinct from the whole body of producers, whereas they consist of precisely the same persons.”

But in regard to demand and supply of particular commodities (not general demand and supply), the increase of the demand is not necessarily followed by an increased supply, or vice versa. Out of the total production (which constitutes general demand) a varying amount, sometimes more, sometimes less, may be directed by the desires of men to the purchase of some given thing. This should be borne in mind, in connection with the future discussion of over-production. The identity of general demand with general supply shows there can be no general over-production: but so long as there exists the possibility that the demand for a particular commodity may diminish without a corresponding effect being thereby produced on the supply of that commodity, by a necessary connection, we see that there may be over-production of particular commodities; that is, a production in excess of the demand.

The proper mathematical analogy [between demand and supply] is that of an equation. If unequal at any moment, competition equalizes them, and the manner in which this is done is by an adjustment of the value. If the demand increases, the value rises; if the demand diminishes, the value falls; again, if the supply falls off, the value rises; and falls, if the supply is increased. The rise or the fall continues until the demand and supply are again equal to one a...