- 211 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This updated edition provides research scientists, microbiologists, process engineers, and plant managers with an authoritative resource on basic microbiology, manufacturing hygiene, and product preservation. It offers a contemporary global perspective on the dynamics affecting the industry, including concerns about preservatives, natural ingredients, small manufacturing, resistant microbes, and susceptible populations. Professional researchers in the cosmetic as well as the pharmaceutical industry will find this an indispensable textbook for in-house training that improves the delivery of information essential to the development and manufacturing of safe high-quality products

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Cosmetic Microbiology by Philip A. Geis in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Dermatology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Basic Microbiology

Peter J. King

Introduction to Microbiology

The Prokaryotes

The Bacteria

The Fungi

Common Contaminants in the Cosmetics Industry

References

Introduction to Microbiology

This chapter will serve as a primer for those new to microbiology and as an updated reference for those familiar with the science. The discipline of microbiology has advanced rapidly since the refinement of Galileo’s light microscope by Van Leeuwenhoek (1674), the disproving of spontaneous generation by Pasteur (1861), the elucidation of the links between specific microbes and human diseases by Koch (1876), and the discovery of viruses by Ivanovsky and Beijerinck (1892). The rate of discovery since the early 1800s represents a mirror of the development of the microbiological techniques used to culture, identify, and characterize microorganisms of all classes. Collectively, the combination of microbiologic techniques and the resulting description of the properties of microbes led to the evolution of impactful techniques of detection of microbes and development of methods for the prevention and treatment of human infectious diseases. While modern microbiology focuses on bacteria (living prokaryotic organisms) and viruses (non-living biologic entities), prions (infectious proteins), protozoa (unicellular eukaryotes), fungi (unicellular and multicellular eukaryotes), and helminths (multi-cellular eukaryotic worms) are generally studied under the microbiology umbrella. This chapter will focus on bacteria and fungi and the methods to detect the presence of bacterial and fungal organisms.

The Prokaryotes

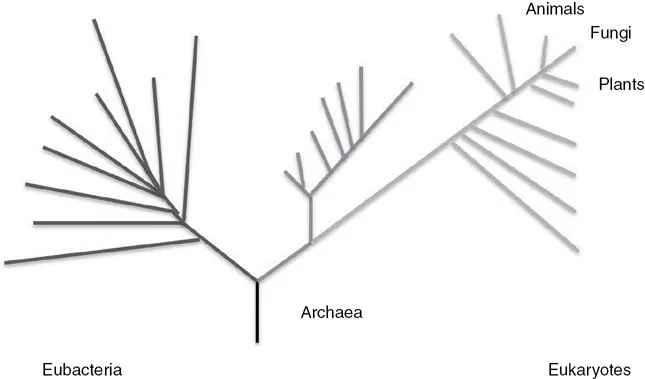

All living cells on the planet can be separated into having either a eukaryotic or a prokaryotic cell structure. Prokaryotes (“before the nucleus”) have a simple cell structure comprising a cell membrane and an internal fluid environment called the cytosol. Eukaryotic cells (“true nucleus”) have these components as well as multiple membrane-enclosed “organelles” evolved for specific functions just like the nucleus. While eukaryotes can be subdivided into plant-like and animal-like cell types, extant prokaryotes can be classified into two major phylogenetic groups based on genomic sequencing, specifically that of 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) genes (Figure 1.1) (1). The first prokaryotic group, which appears to have given rise evolutionarily to eukaryotic cells, belongs to the domain Archaea, the archaebacteria. These organisms appear to represent more ancient forms of prokaryotic cells, many of which evolved to occupy extreme niches such as hydrothermal vents and extreme acid and alkali environments. Although these organisms are fascinating due to their mechanisms of adaptation to these environments and their similarity to eukaryotes, and have proven useful in biotechnology, no known human pathogens fall into this group, and therefore, they will not be emphasized in this chapter. The second phylogenetic group of extant prokaryotes is within the domain Bacteria, the eubacteria. The group (“true bacteria”) reflects their perceived position as the more recently evolved and are the most commonly studied prokaryotes, including all known human pathogenic prokaryotes. Archaea and Bacteria are commonly referred to collectively as prokaryotes although more modern approaches have led most to suggest that the archaebacteria and eubacteria are different enough, that grouping them together is not scientifically accurate, and that the term “prokaryote” should be replaced with the term “bacteria”, referring to the domain Bacteria exclusively. The eubacteria comprise 5,000 known species with new species being discovered almost daily, including those found as cosmetic contaminants. The common structures, genetics, metabolism, growth, and diversity of eubacteria will be discussed in detail in this chapter and the terms eubacteria and bacteria will be used interchangeably.

FIGURE 1.1The universal phylogenetic tree. Relationship comparisons based on comparison of 16S rRNA sequences where the longer the line and spacing, the more distant the evolutionary relationship. Only certain lineages are depicted.

The Bacteria

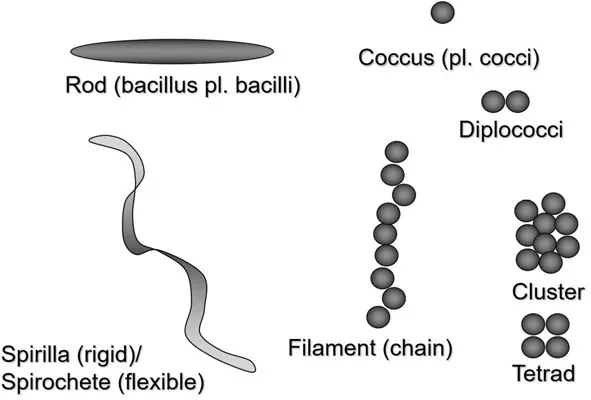

Summarizing the observed types of bacterial shapes and sizes is difficult due to the far-ranging diversity of the bacteria. However, in general eubacterial species range from very small (nanobacteria, 0.05 mm–0.2 mm in diameter) to very large (Epulopiscium fisheloni, 600 mm × 80 mm). An “average-sized” bacterium such as Escherichia coli is 1.5 mm × 2.6 μm. The most basic morphologies observed in bacteria are the coccus (pl. cocci) and the bacillus or “rod” (pl. bacilli) (Figure 1.2). In addition, the cocci and bacilli can associate in characteristic arrangements such as in pairs of two or four, chains, or filaments and clusters. Many bacteria can be identified by these characteristic arrangements such as Staphylococcus (grape-like clusters of cocci) and Streptococcus (chains of cocci) species. Several bacteria are characterized by a spiral or corkscrew morphology such as the Vibrio, the Spirilla, and the Spirochetes. An additional “morphology” observed in bacteria is amorphic or pleomorphic where consistent regular morphologies are not observed usually due to the lack of a rigid cell wall as observed in the genus Mycoplasma.

FIGURE 1.2Common bacterial morphologies. Representative bacterial morphologies are shown. Note that all possible morphologies are not depicted including pleomorphic.

Bacterial Cell Structure

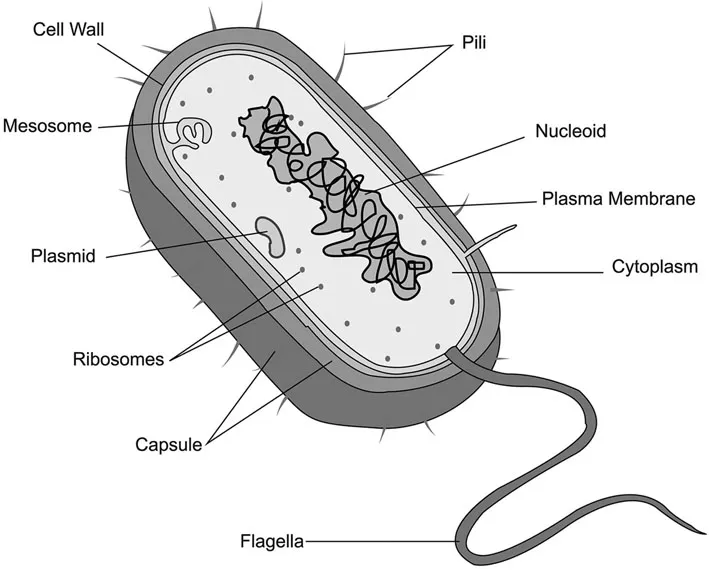

The bacteria share several common structural characteristics with eukaryotic cells such as an outer cell membrane and an internal cytosol. In bacteria, together these are referred to as the “protoplast”. However, whereas eukaryotic cells have internal membrane-bound organelles (e.g., the nucleus), bacteria lack these internal organelles and hence the moniker “prokaryotes”, reflecting a common belief that eukaryotic cells evolved from such progenitors. Several observable bacterial cell structures as well as their composition and function(s) are listed in the section that follows (see Figure 1.3). Special attention is given to the bacterial cell wall.

FIGURE 1.3Common intracellular structures observed in bacteria. Note that not all structures described in the text are depicted.

Plasma membrane—A phospholipid bilayer which creates a semi-permeable barrier and delineates the boundaries of the cell. This is the location of many important membrane-associated proteins including receptors and enzymes as well as transport proteins designed to internalize desired extracellular components and to extrude cellular contents such as waste.

Nucleoid—Although bacteria do not have a membrane-bound nucleus where DNA is contained, the bacteria do organize and compartmentalize their DNA. The nucleoid is a DNA-rich region within the bacteria cell where DNA has been compacted to allow it fit within the cell. Rather than being haphazardly condensed, bacterial nucleoids have specific sequences contained within specific areas of the nucleoid to optimize the use of DNA.

Inclusions and vacuoles—These very small membrane-bound structures represent micro-organization of nutrients and waste for storage and transport. In the case of gas vacuoles, some bacteria in aqueous environments use these for buoyancy.

Ribosomes—Observable under the microscope, these macro-protein RNA molecular machines are the protein synthesis apparatus of the cell.

Capsules and slime layers—These are extracellular layers of carbohydrates that are well organized and firmly attached to the cell (capsule) or disorganized and loosely attached to the cell (slime layer) that are utilized for attachment to surfaces and sometimes to avoid host immune responses.

Fimbriae—These are fine hair-like projections from the cell that are often found in large numbers and are used to attach to surfaces and for “twitching” motility.

Pili—Also called “sex pili”, these are found in smaller numbers that fimbriae (1 or 2 per cell). Pili are large-diameter proteinaceous “tubes” used for conjugation among bacteria where DNA is transferred between members of the same species or even between different species.

Flagella—These large proteinaceous machines are anchored to the bacterial membrane and cell wall structures and are “spun” to create swimming or swarming motility for those species that possess them. The flagella with its whip-like structure help motile bacteria to swim toward or away from certain substances by “chemotaxis”.

Endospore—In a few genera, bacteria can internally generate this protective structure by a process termed “sporulation” usually induced by unfavorable conditions. The endospore is an environmentally resistant, metabolically inert structure which contains, at the least, the bacterial DNA, some proteins, calcium, and dipicolinic acid. Upon the return of favorable conditions, the endospore can reproduce the growing form of the bacteria by “vegetation” or outgrowth. Few genera contain spore-forming bacteria, most notably the Clostridium and Bacillus genera form spores.

S-layer—Some bacteria have an external covering comprising glycoproteins, which is part of bacterial cell wall components. S-layers provide structural integrity as well as facilitate adhesion to surfaces and in some cases help avoid host immune responses.

Bacterial Cell Wall

Free-living bacteria require protection against osmotic stresses. Osmotic stress is encountered when bacteria enter hypotonic or hypertonic environments depending on...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Dedication

- Preface

- About the Editor

- List of Contributors

- 1 Basic Microbiology

- 2 Preservatives and Preservation

- 3 Natural Preservatives

- 4 Multifunctional Ingredients

- 5 Preservative Resistance

- 6 Antimicrobial Preservative Efficacy and Microbial Content Testing*

- 7 Rapid Methods in Cosmetic Microbiology

- 8 Prevention of Microbial Contamination during Manufacturing

- 9 Microbial Monitoring of a Manufacturing Facility

- 10 Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Point (HACCP) Protocols in Cosmetic Microbiology

- 11 Manufacturing MicrobiologyA View of the Future

- 12 Consumer Safety Considerations of Cosmetic Preservation*

- 13 Global Regulation of Preservatives and Cosmetic Preservatives

- Index