Whenever we look back in time, we inevitably find a rich collection of wrong predictions (see Box 1.1).

Box 1.1 Wrong predictions: some examples

Thomas Watson, head of IBM (1943): “I think there is a world market for about five computers”.

Bill Gates (1981): “640K ought to be enough for anybody”.

Popular Mechanics magazine, on the relentless march of science (1949): “Computers in the future may weigh no more than 1.5 tons”.

An engineer at the Advanced Computing Systems Division of IBM, commenting on the microchip (1968): “But what…is it good for?”

Ken Olson, founder and president of Digital Equipment Corporation (1977): “There is no reason anyone would want a computer in their home”.

But wrong predictions are not limited to computer science. In 1876, US President Rutherford B. Hayes said to Alexander Graham Bell when he patented the telephone (invented by Antonio Meucci): “It's a great invention, but who would ever want to use one?”

And a Western Union internal memo (1876): “This ‘telephone’ has too many shortcomings to be seriously considered as a means of communication. The device is inherently of no value to us”.

David Sarnoff's associates, in response to a request for investment in the radio (1920): “The wireless music box has no imaginable commercial value. Who would pay for a message sent to nobody in particular?”

Dr. Pierre Pachet, Professor of physiology in Toulouse (1872): “Louis Pasteur's theory of germs is ridiculous fiction”.

A president of the Michigan Savings Bank, talking to Henry Ford (1908): “The horse is here to stay, but the automobile is a novelty – a fad”.

Lord Kelvin, President of the Royal Society (1895): “No balloon and no aeroplane will ever be practically successful. Heavier-than-air flying machines are impossible”.

Charles H. Duell, commissioner of the US Patent and Trademark Office (1899): “Everything that can be invented has been invented”.

In truth, however, the central question is not whether the prediction is correct or not, but rather which actions and consequences result from it. Forecasts are crucial even when they are contradicted by facts, because they affect decisions and contribute to strategic change in development policies.

According to Bishop (1980): “People often ask me how often I find I havebeen right, when I look back and think about the forecasts I made in the past … but they are asking the wrong question. What we really ask of futures studies is how useful a forecast is. A forecast can be disproved and maintain its usefulness, especially if it is a negative forecast which outlines possible problems or even disasters. If the prediction is taken seriously, someone will work to prevent and avoid the problem. The forecast itself will therefore be ‘wrong’, but it will have contributed to the creation of a better future. In futures studies, the most useful forecasts do not necessarily give an accurate and faithful image of what will happen. Rather, they provide an understanding of the dynamics of change, of how certain events might occur, given specific circumstances; their aim is therefore to offer tools which enable people to choose their own future, and to start creating it” (Our translation, N.d.T.).

Most events, in their complexity, are not predictable (as Niels Bohr said, “Prediction is very difficult, especially if it's about the future”), but if we are generally unable to predict the future state of a complex system, we can predict its possible future states, in other words, its structure. Lindberg and Herzog (1998) quote the mathematician Ben Geoertzel, who distinguishes between prediction of state and prediction of structure: the state of a chaotic system is unpredictable (i.e., a specific weather condition), but the structure, the sum of its possible states, can be easily inferred (i.e., the climate of a specific region).

Complexity generates bewilderment since it makes it increasingly difficult to take decisions. To decide, you have to come to terms with the uncertainty and the impossibility of prediction, “because you can never know for sure how other choices would have turned out” (Jaques, 1991:108).

The future is not written, but remains to be done. It is multiple, indeterminate and open to a wide array of possibilities. The actions we take mold the future into what we expect it to be. As Charles Handy (1996) writes, we need to learn new ways of “handling” the future: “the past might not be the best guide to the future, […] we must, however, be wary that the future needs to be rooted in the past if it is to be real”.

The path is certainly fraught with obstacles. Nothing stays still. Complexity is the space of possibilities, the future is a combination of changing situations, and we must learn to accept uncertainty: in our environment, in our organizations, in every decision we make.

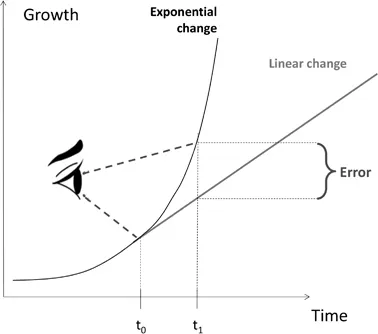

Because of our increasingly unstable and discontinuous context, and of the ever greater impact it has on our lives, we believe that the 21st century will bring about a big change in perspective for men and organizations alike. We just learned it the hard way with the financial crisis of 2008, which lasts to the present day.

The word “crisis” recalls the adjective “critical”: men and organizations live in a complex world, in a network made of diverse and manifold players, in a system where dynamism, uncertainty and acceleration are essential features. How can men and organizations manage the unpredictable? What is the most suitable approach to the future? What are we doing to prepare for the future today? If we wish to navigate the network of the present and the labyrinth of the future, we need to understand the complex forces that induce change. And to adopt the most suitable forms of organization and the right methodologies.

The good thing is that opportunities also increase exponentially. Indeed, “everything is possible, but, perhaps, nothing will be achieved. Conversely, anything can be. Perhaps it is about the immeasurable reserves of Being, the inexhaustible supply of forces not deployed. Forces that no dream forbids us to use tomorrow” (Neher, 1977, in De Toni and Comello, 2005) (our translation, N.d.T.). There are countless possible futures, and men and companies must be ready to seize upon every hint of opportunity. As Vicari (1998:61) argues: “Complexity can be a great opportunity, as long as we are able to convince ourselves that unpredictability is not a hindrance, not a problem, not a malfunction. On these premises, complexity can open new spaces for creativity, innovation, change” (our translation, N.d.T.).

For men and organizations alike, it is a bad idea to stop and wait for events to follow their course, or to simply bet on the future. But if they make an effort and try to act proactively, to grasp weak signals ahead of time, sometimes (and this is especially true for larger companies, or for those which are keystone in their field) th...