- 556 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book provides a historical ethnography of the islands of Zanzibar and Pemba. It describes local legends, and their important social function in recording and constituting the oral history of the islands. The book also provides a detailed and lively account of the society in the islands.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Zanzibar by W.H. Ingrams,F.B. Pearce in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Regional Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I HISTORICAL

A. EARLY HISTORY AND EXTERNAL INFLUENCES

CHAPTER III

INTRODUCTORY

UNTIL recent times very little of the history of Zanzibar has been chronicled in writing, and, with the exception of occasional glimpses vouchsafed to us in the writings of ancient and mediceval authors, the history is largely a matter of conjecture, to be drawn from comparison of customs, etc., with those of other peoples. The history of Zanzibar is there fore to be compiled from the following sources:

(a) Speech, (b) customs, (c) archceological remains and antiquities, (d) legend and tradition, (e) the writings of various historians and travellers, (f) native written recoras where such exist, and, in the case of the latest period, (g) official documents and printed books.

Zanzibar owes its history mainly to its insularity, to its convenience as a jumping-off place for the east coast of Africa, to its proximity to Asia, and to the trade winds or monsoons, which account to a large extent for its close political and commercial connection from the earliest times with India, the countries bordering on the Persian Gulf, and the Re'd Sea.

THE STONE AGE

There is no trace of Zanzibar or Pemba having been inhabited during either Stone Age.

The early Bantu people were formed by an admixture of Hamites, who came across India and Arabia and mixed with the negro people whose cradle was probably in the region of the great lakes. Passing over the " Horn of Africa," where they met and mixed with negroes, the Hamites found their way down south and mixed with the Bushmen to form the Hottentots. This southern way was soon closed by the negroes and mixed tribes. Unrecognized by the pure Hamites, to whom purity of breed was of importance, these mixed tribes were forced more and more to the society of the negroes, and thus the early Bantu tribes were formed of negro people with a smattering of Hamite blood.

THE FIRST INHABITANTS OF ZANZIBAR

At what date men first came it is impossible to say, but that they were firmly established before the beginning of the Christian era, and before the Bantu invasion, can hardly be doubted. It is even possible that they were there during neolithic times, though no trace of stone implements has yet been found.

They were no doubt negroes, and of a stature taller than that of Zanzibar's inhabitants to-day. We may say with certainty that they were fishermen and sailors, and they used dug-out canoes and wicker fish traps. They ate at least turtle and fish. They may have lived in caves; they certainly worshipped at them and at trees. Their gods were tree spirits, and perhaps later the sun.

EARLY INFLUENCES ON ZANZIBAR CIVILIZATION

THE HELIOLITHIC CULTURE

The use of this term requires a little explanation. The time of this culture extended from about fifteen thousand to three thousand years ago. The term is derived from the outstanding feature of the age, the erection of sun-stones. It would be unwise to say that the cult, which spread over the coasts of India, Africa and Arabia, touched Zanzibar itself at the time it flourished, but there is no doubt that certain of the practices of the age affected the people who were afterwards to colonize the islands.

They include the following: ( 1) Circumcision. (2) The couvade, sending the father to bed at the birth of a child. (3) Massage. (4) Making of mummies. (S) Megalithic monuments. (6) Artificial deformation of the heads of the young by bandages. (7) Tattooing. (8) Religious association of the sun and the serpent. (9) Swastika.

Of these customs (1) and (3) definitely obtain in Zanzibar; as regards (4), mummified blood is used in magic; as regards (5), several customs connected with dolmen worship obtain; (7) a debased form of tattoo ing is known; (8) occurs in the Nature myth common in Zanzibar, that eclipses of the solar orb are due to the sun being attacked by a snake; and (9) occurs, though no meaning is attached to it. It is often used in decorations. The dug-out canoe, which has been a feature of Zanzibar for thousands of years, was also an integral part of the heliolithic cult.

Sir Norman Lockyer states that the geographical distribution of rag offerings coincides with the exist ence of monoliths and dolmens. Rag offerings are made in Zanzibar at wells, caves and prominent thickets of trees, and, of course, on the shore an'd on prominent rocks. These rocks, some of which I have seen, are the nearest thing to menhirs in the island, some of them being in pillar form. There are no true menhirs, for the all-sufficient reason that there is no suitable stone with which to make them.

The originators of this cult were brown-skinned men, and it reached over the Mediterranean, through India, up the Pacific coast of China, and spread across to Mexico and Peru. The practices referred to spread all over that region, but did not get far north, nor farther south than Equatorial Africa. It was a coastal cult, not reaching deeply inland.

THE SUMERIANS

From about 6000 to 3000 B.c. flourished a wonderful civilization in the region of the Euphrates and the Tigris, and during this long period came probably the first forerunners of those yearly visitors to Zanzibar from the shores of the Persian Gulf.

These Sumerians were not the Semites of to-day, nor were they Aryans, though they were possibly of Iberian or Dravidian affinities. There are traces of their language and magic on the coast of East Africa to-day. The affinities of Sumerian with Bantu were first suggested by Burton in 1885, and more have been shown by Mr. Crabtree in Primitive Speech. In addition to similarities of words, there are also peculiarities of grammar and construction common to both.

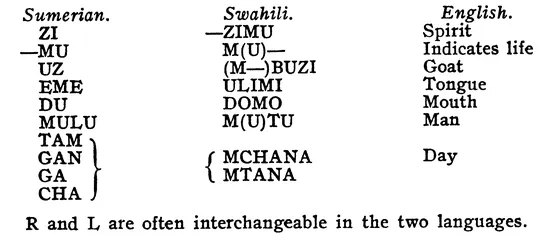

The following examples of Sumerian and Swahili words show such a similarity that it seems almost certain the Swahili is derived from the Sumerian.

As regards the grammar and construction of the language, the following parallels are worthy of note:

- ( 1) Almost universal thematic harmony of the vowels.

- (2) Formation of the greater number of derivatives by means of suffixes.

- (3) System of declension by means of casual suffixes to the root word without affecting any change in it.

- (4) Absence of any distinction between masculine and feminine genders.

- (5) Existence of a negative conjugation.

- (6) The use of verbal forms instead of conjunc tions.

" They developed their civilization, their writing and their shipping, through a period that may be twice as long as the whole period from the Christian era to the present time " (Wells).

At Nippur the Sumerians built a temple to their god, while at Eridu they had their seaport from which the first ships sailed and ventured on the Persian Gulf, to come afterwards farther afield, and possibly to visit Zanzibar on the wings of the north east monsoon. Eridu is now miles from the sea, and but five miles from Ur of the Chaldees, but it remained the seaport down to not later than 5000 B.c. These Sumerians appear to have developed from an agricultural into a nautical people. This seems the more apparent as they had in their language no true word for river, which they represented by two ideo graphs meaning the watery deep, and the spirit of the deep must have been a chief object of worship at the time when the primitive hieroglyphs were first formed. The '' ship, too, played a prominent part in the life of their inventors, and the picture of it represented it as moved not by oars, but by a sail " (Sayce). It may be noted here that the primitive Babylonian picture of a boat is strikingly like that of Egypt.

THE ASSYRIANS

About the year 2750 B.c. there arose among the Semitic peoples to the west of Babylon a great leader, Sargon I, who united them, conquered the Sumerians, and extended his rule from beyond the Persian Gulf on the east as far westward as the Mediterranean. This empire lasted for two hundred years, but while they were soldiers these Semites were barbarians, and therefore became absorbed in the Sumerian civilization. " This Sumerian learning had a very great vitality" (Wells). It survived many vicissitudes, and through the medium of many who absorbed it or who were absorbed by it, passed its traces on to many lands.

As the Akkadian Empire of Sargon lost its pristine vigour, two other peoples rose in power: first the Amorites and then the Elamites. These gave way before the Assyrians, who came from higher up the Tigris, and took Babylon about 1100 B.C. under Tiglath Pileser I.

A Babylonian cylinder shows the Assyrian Hercules, Nin, wrestling with an ox, and then, crowned with the horns of the ox, wrestling with a lion, and it is generally considered that this is the origin of the horn as a sign of chief tainship. As such a symbol the horn is common in East Africa among the descendants of the Persian Zinj Empire.

The Assyrian Empire lasted for about five hundred years, and under Sennacherib extended its conquests considerably, until the career of his army was cut short by pestilence in Egypt.

THE CHALDEANS, MEDES AND PERSIANS

The Assyrian Empire was brought to a close by its def eat at the hands of the Chaldeans, who, with the Medes and Persians, took Nineveh in 606 B.C. This Chaldean Empire did not last long; its great figure was Nebuchadnezzar the Great.

The last Chaldean king was N abonidus, who was remarkable for the impetus he gave to sea-going trade. In his time dhows traded between Babylon, India and China, and the encouragement he gave to this led to further explorations, so that it was not long before there were settlements of Hindus in Arabia, East Africa and China. The Hindus not only made trade settlements on the coast, dating from the seventh century B.c., but apparently, as has already been related, penetrated inland towards the region of the great lakes.

Nabonidus was defeated by Cyrus in 539 B.C.

There are many striking similarities between the magic of the Chaldeans and that practised m Zanzibar to-day.

Having traced the history of the Persian Gulf and its influence on the history of East Africa down to the time of its conquest by the Chaldeans, we must now go back some centuries to the head of the Red Sea in order to trace the connection of ancient Egypt with the coast.

CHAPTER IV EARLY INFLUENCES ON ZANZIBAR CIVILIZATION—continued

THE ANCIENT EGYPTIANS

THE time of the Pharaohs of Egypt must be especially interesting to the historian of Zanzibar, not only because of the fact that they too brought their customs and magic to Eastern Africa, but also because under their auspices were made the first voyages as far as Zanzibar of which there are historic accounts.

The ancient Egyptians had a very important trading mart at a place called Punt, which has been identified as probably being in the modern Somaliland. This Punt is frequently mentioned in the history of Egypt, and seems to have been a place much of the same kind as the Zanzibar of to-day, where the goods of the Orient and of Africa were brought to be sent to Egypt. Vessels from Arabia, Persia and even India probably traded there, and possibly also from the Zanzibar coast, so that it is conceivable that the Egyptians called at Zanzibar in very early times indeed.

As far back as the Vlth Dynasty an expedition to Punt is recorded, and Sankkhara, who flourished in the Xlth Dynasty, traded there. During this period of the Middle Kingdom (3358-1703 B.c.), three dynasties of H yksos or Shepherd kings flourished from 2214 B.C. to 1703 B.C. These Hyksos who conquered Egypt were probably Semitic, speaking a language of the Western Semitic type. They came from Canaan. These migrants were first called Aamu, and latterly Arapin, though at what date they obtained the latter appellation has not been stated. Arapin, of course, means Arabs, and Arabs were first spoken of in the reign of Solomon, about rooo B.C. "The Kings of Arabia controlled the trade of the old world much as does the Seyyid of to-day" (Crabtree). Some of these people wandered into the interior and some followed the coast. Those that went into the interior lost their nationality and became, claims Mr. Crab tree, the origin of the Hamites. The remainder were called Arabs. The reign of the Hyksos kings, he says, marks the zenith of their migration, and its close marks the point where the racial history of Eastern and Central Africa become more or less fixed.

During the Empire (Dynasties XVIII to XX) 1703 B.c. to 11 ro much foreign trade and conquest took place. Queen Hatasu of the XVIIIth Dynasty had relations with Punt, and Seti of the XIX th ( 1400-1280 B.c.) boasted at Sesibi, in the modern Abyssinia, that his dominions reached southward '.'to the arms of the winds."

Herodotus records that Rameses II (Sesostris) dispatched an expedition about 1400 B.c., which perhaps reached Madagascar. Rameses III was also a great imperialist. But the crowning feat of naviga tion was achieved when N eco of the XXVlth Dynasty (630-527 B.c.) dispatched a fleet of Phrenicians from the Gulf of Suez with abundant supplies, which sailed southward till they had the sun at noontide upon their starboard, i.e., rounded the Cape of Good Hope, and sailed back northward by the Atlantic, the Straits of Gibraltar and the Mediterranean, till they reached Egypt again. They took three years to do it, and landed each year long enough to sow a crop of wheat and harvest it.

" The importance of these expeditions to Punt cannot be over-estimated. They are the earliest attempt at organizing a fleet of powerful ships to voyage far away from home waters " (Keble Chatterton). A picture of a Punt expedition is preserved in Queen Hatshop-situ's temple, and a description of it will be of interest. There are five ships arriving, two of which are moored. The first has sent out a small boat, which is fastened by ropes to a tree on the shore, and bags and amphorre, probably containing food and drink as presents to the chief, are being unloaded. Then the produce of Punt can be seen being loaded on. There are bags of incense and gold, ebony, ivory tusks, leopard skins, and trees of frankincense piled upon the decks. These were probably not all domestic produce, but represented goods brought from other ports.

We have seen above that these ancient Egyptians were great navigators. Their ships were in all probability derived, as w...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- PREFACE

- Dedication

- Contents

- INTRODUCTORY

- PART I—HISTORICAL

- A. EARLY HISTORY AND EXTERNAL INFLUENCES

- B. LATER HISTORY OF THE NATIVE TRIBES

- C. HISTORY OF MODERN ZANZIBAR

- PART II—ETHNOLOGICAL

- A. FOREIGN INFLUENCES

- B. NATIVE TRIBES OF ZANZIBAR

- BIBLIOGRAPHY

- INDEX