- 194 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Talking Beyond the Page shows how different kinds of picturebooks can be used with children of all ages and highlights the positive educational gains to be made from reading, sharing, talking and writing about picturebooks.

With contributions from some of the world's leading experts, chapters in this book consider how:

- children think about and respond to visual images and other aspects of picturebooks

- children's responses can be qualitatively improved by encouraging them to think and talk about picturebooks before, during and after reading them

- the non-text features of picturebooks, when considered in their own right, can help readers to make more sense out of the book

- different kinds of picturebooks, such as wordless, postmodern, multimodal and graphic novels, are structured

- children can respond creatively to picturebooks as art forms

- picturebooks can help children deal with complex issues in their lives

Talking beyond the Page also includes an exclusive interview with Anthony Browne who shares thoughts about his work as an author illustrator.

This inspiring and thought provoking book is essential reading for teachers, student teachers, literacy consultants, academics interested in picturebook research and those organising and teaching on teacher education courses in children's literature and literacy.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Talking Beyond the Page by Janet Evans in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Pedagogía & Educación general. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One

What to respond to? Attending to aspects of picturebooks

Introduction

It isn’t enough to just read a book, one must talk about it as well

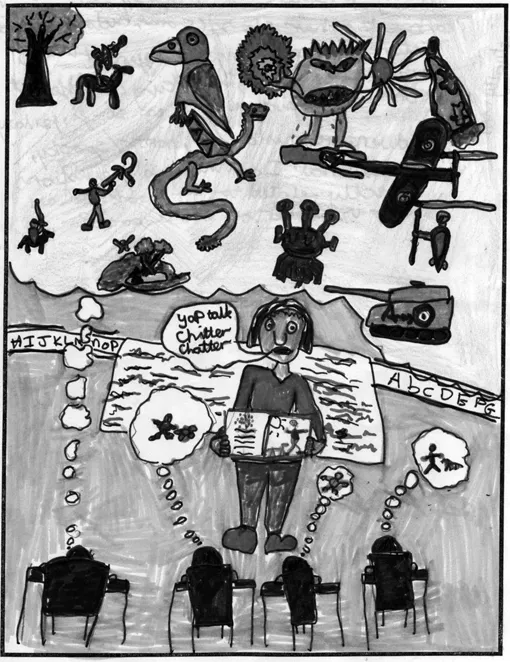

Figure 14 Cameron, aged 11: In my picture a teacher is reading a book to her class (some children are hidden at the side of the picture). All are thinking different things but one child, actually me, is thinking of different genres of picturebooks, for example: sci-fi, fantasy, adventure, historical, horror/spooky, traditional. I am thinking of questions directly related to the book, such as ‘Who is the person in the book?’

Some books are easy to read and do not seem to need much interpretation or deep thought to understand them. However, many books are more complex and some readers find them difficult to understand. This may be because of the plot itself, the complexity of the characters, conflict within the storyline, or the resolution (or lack of resolution); or it could even be a reader’s differing background knowledge and cultural dissonance with what the text is saying. Such difficulties may apply to narratives in general, but they also apply when we focus on picturebooks in particular. Just because picturebooks are shorter, have fewer words and of course have illustrations, does not necessarily make them easier to read; in fact many are extremely complex multimodal texts that often make great intellectual and cognitive demands on the reader.

If books can sometimes be difficult to understand, how can we help readers to unpick, comprehend and of course enjoy what they read? The answer that emerges again and again is responding to texts through collaborative talk. A body of research has developed, focusing on how children learn through talk, (Corden, 2002; Goodwin, 2001; Jarrett, 2006; Myhill, 2006). In addition, there is an increasing body of research focusing specifically on how talk helps children to respond to and understand texts. (Baddeley & Eddershaw, 1994; Chambers, 1993; Evans, 1998; Graham, 1990; Reedy, 2006; Sipe, 2008; Styles & Bearne, 2003; Watson & Styles, 1996).

Sharing and responding to books

When reading picturebooks I frequently feel the need to have someone to share them with, someone with whom I can enjoy the books – enjoyment being one of the principal reasons that most people read narrative picture-books – but also someone with whom I can feel comfortable about asking tentative questions or sharing some of my thoughts, observations and queries in relation to the meaning of the book. The analogy of a journey has been used many times to represent this notion of reading and understanding, but it is a pertinent analogy: reading a book from beginning to end is like a journey, and it is good to have someone to share the journey with you – someone to guide you and go with you as you travel through the book and as you read the story. Metzger seems to be in accordance with this journey idea, and he gives us some indication of how easy and at the same time how difficult the understanding of narrative books can be:

Stories go in circles. They don’t go in straight lines. So it helps if you listen in circles because there are stories inside stories and stories between stories and finding your way through them is as easy and as hard as finding your way home. And part of the finding is the getting lost. If you’re lost, you really start to look around and listen. Moral: be prepared to take risks.

Metzger (1979)

So, just reading the book itself is hardly ever enough! It is the shared oral responses and the ensuing discussions that allow fuller and maybe differing understandings to take place. Think about the reasons that book clubs and reading circles, where people read books alone prior to discussing them, are so successful. It is the enjoyment of talking about and responding to what has been read in a comfortable, unthreatening environment with like-minded people that is one of their main successes.

Talking about books … collaboratively

How could this way of talking about and responding to books with others be emulated with young children without the discussion becoming a mere question-and-answer session? Kathy Short (1990) looked at the importance of book talk with children between the ages of 5 and 11. She later stated (1997: 64) that ‘Children should enter the story world of fiction and non-fiction to learn about life and make sense of their world, not to answer a series of questions.’ Short gave the name ‘literature circles’ to the way of responding to and talking about books in small group, literature-based discussions. Daniels (1994) further developed this concept and showed how such groups could be used by teachers to encourage children to respond to books. Literature circles provide a very effective way of enabling teachers and children to respond to picturebooks, but they are still not used enough in classrooms! Many children read books alone without sharing them or talking about them; this is hardly ever enough to enable in-depth, meaningful understandings to take place.

Shirley Brice Heath shared this sentiment when, in her seminal text, Ways With Words (1985), she stressed the importance of talk by stating that ‘For those groups of individuals who do not have occasions to talk about what and how meanings are achieved in written materials, important cognitive and interpretive skills which are basic to being literate do not develop.’ Similarly, Smith (2005: 22) in her minibook Making Reading Mean, stated that an approach to reading that focuses on the process and not just the product is needed. She emphasized that we have to ‘get inside children’s minds as they read, so we can see and guide the thought process.’ She went on to say that the best way to do this is through talk. In commenting that children will emulate what they see and experience in their classrooms, she noted that ‘Children who experience talk used in an exploratory and reflective way to think about texts and reading will begin to use that sort of talk themselves. Participating in talk can induct children into new ways of literacy thinking.’ (2005: 23).

Talking about and responding to books in differing ways can include written responses (Hornsby & Wing Jan, 2001), drawings and illustrated responses (Anning & Ring, 2004; Arizpe and Styles, 2003), role play, dramatic enactments and Readers’ Theatre (Dixon et al., 1996), and non-verbal responses including gestures, eye movements and touch (see Chapter 7, and Mackey, 2002). These differing ways of responding to reading all enable fuller understanding to take place; however, it is sometimes the time between readings that allows fuller understanding to develop – this is where our brains are given opportunities to process information. Arizpe and Styles (2003) noted this and found that much of the understanding that children make of books goes on in the thinking and the talking about books, often between rereadings of the same book. Of course, we have to recognize the rights of the reader to not respond at all and to read a book quietly and without interruption (Pennac, 2006). Many people prefer to read silently, but there are also many readers who relish the opportunity to talk about what they have read during and after their read.

Who are picturebooks for?

Talking and responding to picturebooks with other interested readers is one way to develop fuller understanding. However some picturebooks are so complex, so convoluted, and so seemingly difficult to understand, sometimes with subject matter that is deemed by some to be unsuitable for children, that I have often found myself asking who such picturebooks are written for. Would young children make sense of them? Would older, fluent readers dismiss them immediately without taking a second look simply because they have pictures? (see Chapter 5). Are they bought and read by adults as works of art as opposed to being simply books with pictures and narrative storylines? (see Chapter 6). Exactly who is the audience for this kind of picturebook?

In writing about a very early Edward Ardizzone book, one which was published in 1937 and which courted much controversy as a result of its subject matter, perceived at the time as being unsuitable for children, Rebecca Martin posed this exact same question. She asked ‘Who is the audience of children’s books – children, adults or both? How are these audiences different? Is the picture book today just for small children?’ (2000: 243) The Ardizzone book about which Martin was writing was Lucy Brown and Mr Grimes (Ardizonne, 1937). In brief, the story is about a friendship that develops between an orphan girl (who lives with her aunt) and a lonely old man. They meet in the park and he gives her presents when she asks for them. Eventually, after the orphan girl helps him to recuperate from an illness, he formally adopts her and she lives with him and his housekeeper in a beautiful country house. This was Ardizonne’s second title and, in contrast to his first, provoked outrage amongst American librarians, who censored it at the time. The book went out of print and was not reissued for 33 years. The censorship was based on perceived issues of stranger danger (the little orphan girl goes away with an old man – Mr Grimes), potential paedophilia (even in the thirties), and being rewarded for exhibiting bad manners (Lucy is adopted and is showered with gifts of every imaginable kind by her new parent, Mr Grimes). However one reacts to Lucy Brown, the fact is that it was originally written for children.

These kinds of reactions raise questions about picturebooks that challenge the child reader (by dealing with subject matter such as sex, death, adoption, suicide, disability, etc.). Should such books be read alone by children or should adults be available to discuss and respond to the kind of questions that will inevitably be asked? Martin (2000: 249) asks ‘Do small children need more help distinguishing between fact and fantasy? Are they likely to do whatever they see or read about in books, such as talking to strangers?’ There is evidently still much debate about whether children should be protected from such issues in books, but the fact remains that such sensitive and emotional issues can be dealt with if adults are available to discuss any questions or queries that may arise. The importance of responding to books is crucial to enable children to make sense of books at all levels of complexity; whether Lucy Brown was ‘ill-conceived’ or not is immaterial to the fact that children need to be given the opportunity to talk about and respond to texts.

In considering the different ways in which picturebooks can be responded to, Frank Serafini (2007), in a conference paper, proposed four ‘So What?’ points to focus our thoughts. He suggests that:

- The complexity of picturebooks should not be underestimated.

- Teachers need a theoretical foundation and vocabulary to talk about images.

- There are numerous perspectives that one can bring to picturebooks.

- Picturebooks offer a connection between school-based literacies and multiliteracies.

The structure of this book

Some of the four points listed above, as well as many others, are considered in the ten chapters in this book. The book is organised into three parts. In the first part are five chapters that, broadly, look at the aspects of picturebooks that can be focused on to enable the reader to explore, interpret and make sense of the text. These chapters consider:

- how readers can begin to understand visual images

- how readers can respond in many different, multiliterate ways

- an exploration of some children’s responses to a particular, postmodern text

- how the endpapers in picturebooks can be used to determine what a book might be about

- how the frames used by picturebook illustrators affect the way we ‘see’ and consequently respond to the book itself.

The second part takes a closer look at the responses that come from different picturebooks. These chapters consider:

- responses to books as art forms in relation to fine art

- children’s differing responses to multimodal picturebooks

- some immigrant children’s responses to picturebooks and other kinds of visual texts

- how c...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Permissions

- Foreword

- Notes on contributors

- Children’s thoughts about picturebooks

- Part One What to respond to? Attending to aspects of picturebooks

- Part Two Different texts, different responses

- Part Three Thoughts from an author-illustrator

- Index