- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

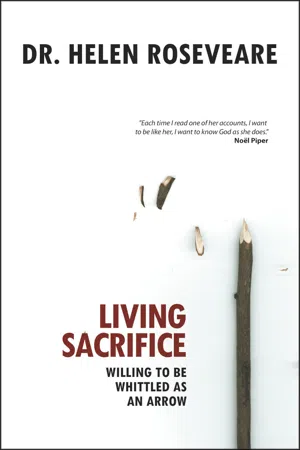

Yes, you can access Living Sacrifice by Helen Roseveare in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

Christian Focus PublicationYear

2007eBook ISBN

97818455095211

WITH ALL MY HEART

Moreover, I will give you a new heart and put a new spirit within you; and I will remove the heart of stone from your flesh and give you a heart of flesh. (Ezek. 36:26)

HOW MUCH I learned in those early months in Africa! First, one had to tackle the language. Our missionary society was working in an area of some fifty thousand square miles, where eighteen different major tribal groups lived. These tribes consisted of eight to eighty thousand people, each with a language completely distinct from its neighbour. Only three or four of these languages had yet been reduced to writing. Throughout the area, two trade languages had grown up to provide a means of intertribal communications: Bangala to the north and Kingwana (now Swahili Zaire) to the south. Ibambi, our central village, where I lived at first, was on the border area between the two trade languages, and to communicate at all freely, one needed to know both of these.

I had travelled the five-week journey from England to Ibambi with two missionary couples returning after furlough. From them, on-board ship, I had my first language lessons. As we slowly steamed down the Suez Canal, it was hard to concentrate on the eight classes of nouns in the Swahili language, with the diversion of a train of camels just a few yards away! Fortunately for me, Swahili is a phonetic, non-tonal language that obeys definite rules and is relatively easy to learn. Plunged into work on arrival, I was forced to use the little I knew, and so made rapid strides.

Adapting to culture and new dietary regimes was honestly little of a problem to me. I was so excited to be there and wanted to become one with the people as fast as I could, that I noticed no barrier or sense of shock. Maybe our fairly rigorous upbringing during the rationing shortages of World War II, and having spent most of childhood’s holidays camping or mountaineering, was a real help in developing an adaptability to any circumstances. And I was so thrill-ed to have arrived in Africa, I would have enjoyed practically anything.

Clinic work for seemingly endless crowds of very sick people filled every day. They never ceased to come. The little room where I worked under a corrugated iron roof was always full and always hot and always noisy. The heat and noise and numbers were appalling. I felt I would never get accustomed to this. The huge, grotesque, stinking ulcers that had eaten away at bodies already thin from malnutrition had to be seen to be believed. The racking coughs, the swollen, pus-filled eyes, the violent intestinal problems, almost overwhelmed me. The countless women with their heads tightly bound with a vine-string to attempt to control a splitting headache, the hot, tired, sweaty bodies burning with malarial fever, were incredible. Babies, desperately thin, with pale, staring eyes and bloated stomachs, tore at my heart continuously.

Would I ever get used to the need? And the pathetic gratitude of the people for anything I could do for them. They loved me: they really did.

One evening, a young boy arrived at Ibambi with a scrawled note on a piece of paper torn from a school exercise book. His father, a village catechist, was ill and unable to get to us. Would I go to see him, please, and take him medicine?

The African who would normally have driven me there was sick. Not only did I not know the way, but I had not as yet begun driving on the rough dirt roads. Jack Scholes, my missionary leader, offered to drive me to the village, and this gave him the opportunity for a talk with me.

“Helen,” he said quietly, looking straight ahead between the walls of elephant grass and over the central, grass-tufted mound of the dirt-track road, “if you think you have come to the mission field because you are a little better than others, because you have more to offer through your medical training, or –” There was nothing censorious in his tone, yet his words cut deep into my heart. Was that the appearance that I had given to others, of a spiritual superiority, that I knew all the answers and would show them how the job should be done? Had I been so busy tackling the needs of the bodies of those who came for help, that I had little or no time, and no inclination to make time, for fellowship with other members of the team?. Did I subconsciously feel that my service to the community through medicine would bring more people to the Saviour than these others had done by years of patient trekking and preaching?

A wave of shame and a sense of failure came over me. I tried not to reply, as a sense of self-pity made itself felt. Why did they misunderstand me? Why did no one appreciate how hard I was working, how tired I was, how much I needed fellowship and support? No one offered to help me, or relieve me on night duty. The “pity-poor-little-me” syndrome started early in my missionary career.

“Remember,” Jack concluded, “the Lord has only one main purpose ultimately in each of our lives, that is to make us more like our Lord Jesus.”

As we talked over the implications of what he was saying, he suggested to me that the next thing God wanted to do in my life to make me more like Jesus, He could not do for me back in Britain, as I was too stubborn and wilful: so He had brought me to Africa, to work in me through Africans.

Another voice spoke quite clearly: “to make you realize and face up to this ‘pity-poor-little-me’ attitude, and become real,” and I turned my head away.

It all seemed such revolutionary teaching. So simple and childlike, it was nevertheless so profound and deeply disturbing. It put all “missionary” work into a new perspective and made me feel very small.

I began to feel the pressures of the medical work. There were so many sick and ill needing help, and so little we could do for them. There was so little space. I needed an examination room where I could be quiet, away from the throng, able to listen to chests and hearts, and to think concisely what could be done for each patient. I needed a pharmacy, for stocking medical supplies, making up mixtures, dispensing drugs to patients through a hatch or some such arrangement. I needed wards where I could care for the more gravely ill, with a section for maternity cases, and another section for isolation. I drew up plans, but it was hard to be simple enough to be realistic. I asked the fellowship’s permission and encouragement to start building. The church agreed, and work commenced on a large mud-and-thatch erection to be divided up for a multipurpose building for women patients. The work was so slow! It rained almost every day, and one does not work in the rain in the tropics! We waited for the poles; we waited for the vines; we waited for thatch. Then, we waited for window and door frames: we waited for lime to plaster the walls: we waited...

It took just over a year. Meanwhile the work went on in our small, overcrowded clinic. A workman at the mission printing press developed acute mastoiditis. We had no antibiotics in the early fifties: they could actually be obtained at the nearest pharmacy-store, fifty miles north, but only at an exorbitant cost. The money we had available was needed to pay the workmen on the site. We stopped work there for a week to buy two small bottles of penicillin. Dared one incise the bulging abscess? The book told me how and where, but I’d never seen it done. The book also warned of all the dangers. We prayed; I incised; the penicillin worked;God touched and the man recovered.

Another man died the following week of the same disease, and I felt sick.

A baby was brought in, severely burned. Over half the surface area of the body had been scorched with boiling palm fat. The textbook warned that cure was impossible. The shock would kill the baby. We laid the baby in the canvas bag I used as a bath in my home, and soaked the body in warm water with bicarbonate of soda borrowed from a missionary’s kitchen. I carefully cut the blisters with boiled-up embroidery scissors. We attempted to sterilize strips of gauze in a biscuit tin over a wood fire, and wrapped all in a clean, brightly coloured, knitted blanket. The baby was laid in a wooden box, on a straw-stuffed mattress, covered with butter-muslin to keep out mosquitoes and flies. The baby did well, I remember, and recovered.

I could not sleep, I was so anxious about the needs around me. What more could I be doing?

A man, a catechist from an outlying church, was carried in, gravely ill with a strangulated hernia. The four bearers had been walking eight days to reach us. I did not do surgery then. I was untrained. It would be unethical to attempt to learn to do operations under the prevailing conditions – so I thought then. He was carried on to a Belgian Red Cross hospital, but he died during the operation.

The first group of African students, who had already gathered round me for training, looked at me accusingly when the news reached us. Their looks said: If we’d operated here, he might have lived.

I did not sleep that night. My heart was tortured with pain. I could not do more. I did not know how to do more. I was not willing to attempt to do more. Slowly the force of my violent arguments lessened, and I realized that God was saying that we should and would do more.

A tiny premature baby was carried to us, about four days old. It looked like a drowned rat. I have never seen anything so tiny and yet alive. But it was all skin and bone. I turned away with a sickening sense of hope-lessness. The baby needed careful incubator care, with controlled drip feeding. Oh, yes, I knew the answers: I knew what the book said. But how?

It was pouring with rain. That was the first time that I ran out into a downpour. I placed a table in the middle of the courtyard, away from all overhanging trees. Hurrying back, I collected a clean cloth and all the glassware I could quickly find and placed all on the table. Twenty minutes later, as the storm abated, the students watching me in mystified silence from the protection of the covered veranda, I collected every-thing again. Measuring a litre of rainwater into a clean saucepan, I boiled it with a heaped spoonful of table salt, and strained it through six layers of gauze bandage. Armed with a syringe and my litre of saline, I took a student into a second room, with the tiny scrap of a baby held in the hand of a tribal woman. I showed the student how to give slow subcutaneous injections of five millilitres of saline at a time, under the loose folds of skin. He continued throughout the day. Another student dropped sugar solution from a syringe into the baby’s gasping mouth, drop by drop, minute by minute, through two days and nights. The baby lived.

Could one keep going? It was not the physical strain alone that was telling on me, but the emotional trauma as well. Day after day, night after night, my heart was torn with the burdens and the needs. Besides which, they all expected me to be able to cope, able to invent, able to improvise. They were all so grateful for anything I did, whether successful or not. My heart was numbed from carrying their burdens.

Then the night came when a newborn baby, apparently healthy, died in the maternity-care centre. It was the first time that I had been faced with this, and somehow, something drawn taut inside me snapped. I could bear no more.

I had been called at about two in the morning by a tap on my bedroom window by a frightened pupil midwife, frightened by the dark, by the fear of evil spirits, by the nearness of death.

I dressed rapidly and ran across to the ward. The baby did not move or cry. I tried to resuscitate it, mouth-to-mouth breathing. I held the slack body against my own body to give it warmth. The baby was dead. There was nothing I could do. The others there had already tried all that I was trying to do and they stood watching me, wearily, in an uneasy silence. I was suddenly, unreasonably, angry. I snapped at the missionary midwife:

“Why didn’t you send for me earlier?”

The implication was obvious: and she in turn, hurt and angry, turned on the senior African midwife, and demanded: “Why didn’t you call me earlier?”

The ball was passed from court to court, as the senior midwife repeated the accusing question to the pupil, and she to the relative of the mother. We ended up in the despairing situation of apparently blaming the mother for the death of her own baby. There was a terrible silence. I left the ward and went back home, sullen in the loneliness of a responsible job. I knew at once that my anger had been unjustified, and that I should not have asked the offensive question. In my heart I knew that I had to carry the final responsibility, that I could not pass it back to others. “Passing the buck” really only goes in one direction, and in our medical service I was the end of the line. But I was angry. Against whom? I didn’t know. Against the system perhaps; against my own frustrating inadequacy and lack of experience and of skill; against the lot of the people where I lived and whom I was growing to love, in their abject poverty. None of this helped the situation.

For three days there was a sense of hostility among patients and pupils and midwives. There was an audible silence when I went over to do a ward round. In the end, God broke through my wall of hurt pride and I apologized for my unfair criticism inferred from the tone of voice in the accusing question. Immediately, the tension eased and slowly relationships were restored and healed.

We were able to discuss the particular case quietly and impersonally to learn from it how to help one another better, should a similar situation recur. God was beginning to show me that this was part of “loving Him with all my heart,” the willingness to accept heart burdens, and the willingness to break and apologize quickly for mistakes made or implied. “The sacrifices of God are a broken spirit; a broken and a contrite heart, 0 God, Thou wilt not despise” (Ps. 51:17). If to love equals to give, then I had to give God my heart to break and to remould and to fill with His overflowing love. I wanted to, and yet I did not want to. I also wanted to retain the right to react and get angry, should I feel a situation warranted it. And God said: “No.”

Something happened soon afterwards that was to re-emphasize this lesson. I was to have gone to a distant forest village for a missionary mother’s confinement: but I became ill with a severe bout of malaria complicated by jaundice. An African went the ninety-mile journey on a bicycle, with a letter from our missionary leader, explaining that I had been ill, but that I would come as soon as I was fit to travel, unless the family could make their way at once to our hospital at Nebobongo, where the mother could be given all the care she needed. This latter course would be preferable, as it would obviate the necessity of the long journey for me, so soon after being so unwell.

The cyclist returned in three days, with a letter for Jack Scholes. Their response was somewhat abrupt, written in apparent annoyance. They mentioned that their only vehicle was “off the road” waiting for a new universal joint. They practically demanded that I fulfil my promised obligations at once. The implication was that I was unaware of priorities, weighing my “trifling sickness” against the possibly serious consequences of a childbirth in the forest with no doctor or nurse present or available...

The news was conveyed to me tactfully and as kindly as possible. I agreed promptly that in a couple of days I would be fit enough to travel, despite slight residual fever and weakness, and so appropriate arrangements were made. Nevertheless, I was angry. I did not really stop to think about the cause of the reactions of that couple. Shut away in the forest, with no medical help and no available transport, they probably knew fear; much as my reaction when the baby died the previous month, and I knew frustration. It was their fear that had given rise to the abrupt letter, as my frustration had precipitated the angry question. Letter and question each carried an implied accusation of irresponsible negligence. The couple in the forest were thinking of themselves and their need: I at Nebobongo, surrounded by patients, had been thinking of myself and my involvement.

My leader knew me pretty well. He had been watching God’s dealings in my life, and had heard my testimony as I sought to respond to this training. He came to see me and have a chat that evening, having discerned fairly accurately all that was going on in my heart.

“Helen,” he said, “you need to learn that what God teaches you in your own circumstances about yourself is to help you to understand others and to see things from their point of view.”

He paused, and in my mind, I turned over what he had said. “That couple are possibly afraid, away there on their own. It may not be easy for them to borrow transportation, and it is a long, rough journey, as you know well. For that young expectant mother it would be a tremendous ordeal. They have not realized how ill you have been, despite my letter to them. And we have to remember that they have been depending on you to see them through at this special time.”

Of course all that he said was absolutely true, and quite easy to see and understand. But I was nursing my grievance, and my right to be hurt by their apparent selfishness.

“I want to ask you to do something – not for me, but for yourself,” he said. “Actually, more truthfully, to do it for Christ’s sake. As you go tomorrow, do all you can to help them. And do not make too much of your illness. Jessie and I respect you for agreeing to go in these circumstances, as we know you are not really fit yet. God gave you the grace to make that decision. Now do not spoil it.”

This was beyond me. What was he getting at?

“Just die to yourself, Helen, and the Lord will, bless you,” Jack continued. “You are going there to help them. Don’t waste time justifying your delay, or underlining your virtue in going at all. You are going as Christ’s servant. You’ll only regret anything you say in haste or in anger: and most probably it would only be in self-defence or self-justification. Can you not trust God with all that? The Lord, when He was reviled, reviled not in return, but He trusted Him who judges rightly (1 Pet. 2:21-24). If you can accept that to these two your delay has caused distress and anxiety, God will help you to go to them in humility and to ask their forgiveness for it.”

These new and searching thoughts chased through my mind. Somewhere deep down, a chord had been struck, and an echo was struggling up through my heart to try to find expression: but my rebellious anger sought to stifle it. Battle raged. I suppose I knew that he was right, but I did not want so high a standard. I wanted the right to blaze and proclaim my innocence of the implied accusation of irresponsible negligence.

And God said: “No.”

God was teaching me, and I was slowly learning. That God did not always allow us to defend ourselves (or even each other, in certain circumstances) seemed very hard to me, particularly if one had clearly been wrongly accused or misjudged. Yet He reminded me that Christ, for my sake, was falsely accused at His trial and made no effort to defend Himself. “Like a sheep that is silent before its shearers, so He did not open His mouth” (Isa. 53:7). Dimly I began to grope toward this higher goal. It was another step towards giving my heart wholly to God that He might love others through me, without my putting obstacles in His way: thus towards loving God with my whole heart.

Revival visited the church. The Holy Spirit was poured out on the local church. For years, senior missionaries and church pastors and faithful African women had been praying earnestly for such a visitation. They had started with one night each month given up to prayer. Then as prayer became more importunate, they added one day each month, set apart for prayer. As the sense of urgency grew, so a daily midday prayer meeting was held. Many spent hours in prayer and fasting on their own as well. God heard.

For ten days, a strange stirring had begun among the local workmen, and the Holy Spirit began a work of conviction in many hearts. Different ones confessed to thefts and returned stolen property. Others confessed to bitterness against white employers, and to jealousies regarding their possessions, and they sought forgiveness. Others again spoke of idleness, wasting their employer’s time, discontent at working conditions: and they began working harder with a better spirit.

Then suddenly, on the Friday evening, at the weekly fellowship meeting, the Holy Spirit was poured out upon the one hundred folk gathered in the Bible school hall. It was indeed a mighty, unforgettable awakening. Initially, there was a repercussion of shock and fear, as all over the hall, people were being shaken by the power of the Spirit, under the grip of conviction of sin, or else in a surge of irrepressible joy and release. Was this truly of God, or had some other spirit come among us?

As we heard the confessions of sin of those deeply convicted by the Spirit, and then how they claimed the shed blood of our Lord Jesus Christ for cleansing and forgiveness; as we saw their faces change and light up with a great inner joy, we knew the movement was truly of God. No other spirit would glorify the Lord Jesus, or convict men of sin, and lead them to the cross for forgiveness. Men and women were under a deep constraint to see sin as very sinful, no longer making excuses for their “weaknesses and failures.” Coldness of heart, petty jealousies, loss of temper, lack of desire for the thin...

Table of contents

- Testimonial

- Title

- Indicia

- Contents

- Foreword to the American Edition

- Foreword to the British Edition

- Prologue – His Right to Demand

- 1 With All My Heart

- 2 With All My Soul

- 3 With All My Mind

- 4 With All My Strength

- Epilogue – My Privilege to Respond

- About the Author

- Other books from Christian Focus

- Christian Focus