- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

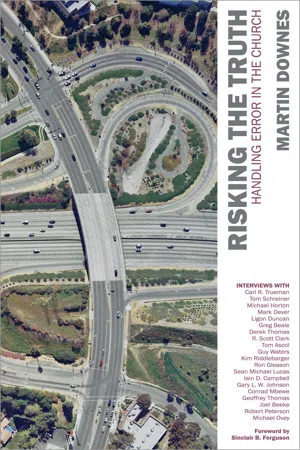

Yes, you can access Risking the Truth by Martin Downes in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

Christian Focus PublicationYear

2009eBook ISBN

9781845506612CHAPTER ONE

HERESY 101

What do you associate that word with? Torches and pitchforks? Burning someone at the stake? The incessant barking of theological watchdogs? ‘Health and wealth’ preachers? Unbelieving bishops who deny the gospel but stay on the payroll of the church?

What is heresy?

One writer defines it as ‘any teaching that directly contradicts the clear and direct witness of the Scriptures on a point of salvific importance.’ Heresy is the kind of doctrinal error that is so serious that it redefines the gospel. Error is always costly. It dishonors God and damages the Church. But not all errors are heresies. A heretic is not someone who fails to explain adequately the doctrine of the Trinity, or that Jesus is both fully God and fully man, the nature of the atonement, or justification by faith alone. No, a heretic denies these truths and is fundamentally unsubmissive to apostolic doctrine and authority as it is given in Scripture.

Heresy is not a matter of opinion. We have an objective standard when we want to find out which theological view is correct or orthodox (meaning ‘right belief’), as Paul shows in 1 Corinthians 15, and which ones are wrong. In the end the fight against heresy is always won by the clear, patient, and thorough exposition of Scripture. Perversely, successful heretics themselves often claim to be truly orthodox and biblical.

Heresy is, however, a matter of choice. It is the choice to believe a different gospel. Augustine said that heretics are men ‘who were altogether broken off and alienated in matters relating to the actual faith.’

A heretic chooses to tell lies about the God of the Bible because he doesn't want to tell the truth. And a heretic is someone who refuses admonition and is divisive (Titus 3:10-11). Putting it mathematically, heretics take away from the truth of the gospel (and adding to the truth always takes away from it), they divide true churches and aim to multiply new disciples.

Where do heresies come from?

It is vitally important to realize that heresies do not originate in the minds of men and women. Ultimately heresy originates with the devil. When the apostle Paul takes the Corinthian church to task for tolerating false teachers he compares their approach to the deception of Eve by the serpent (2 Cor. 11:3). But the deception in the Garden is more than a useful illustration. The super-apostles at Corinth are the servants of the devil disguising themselves as apostles of Christ.

Similarly Paul warned Timothy about ‘deceitful spirits and the teachings of demons’ (1 Tim. 4:1), and of false teachers who are caught in the snare of the devil (2 Tim. 2:24-25). After all the devil is the father of lies (John 8:44). The connection between other Gospels and the demonic, which is integral to a biblical world-view, has been largely lost. If it were regained it would keep us from ever thinking that heresies are interesting, intellectually stimulating, tolerable, or in any way benign. Cyprian of Carthage, in the third century, made this insightful comment about heresy and the devil:

There is more need to fear and beware of the Enemy when he creeps up secretly, when he beguiles us by a show of peace and steals forward by those hidden approaches which have earned him the name of the ‘Serpent’ … He invented heresies and schisms so as to undermine the faith, to corrupt the truth, to sunder our unity. Those whom he failed to keep in the blindness of their old ways he beguiles, and leads them up a new road of illusion.

Or as the late Jaroslav Pelikan put it ‘renouncing the devil means denouncing heresy.’

Furthermore, it is vitally important to understand that heresy is the takeover of Christianity by an alien world-view. Paul warned the Colossians about ‘plausible arguments’ and those who were trying to take them captive by ‘philosophy and empty deceit according to human tradition,’ (Col. 2:4, 8). Heretics often use the words of the Bible, change their meaning, and hide false ideas under them. The label may still say ‘Christ’, ‘salvation’, or ‘atonement’ but the meanings of these words have been radically altered. The early church fathers were alert to this danger. They wrote books to expose the fact that heretics were really saying the same thing as pagan philosophers, only the heretics were dressing up these ideas in Christian language. This deceitfulness makes heresy morally as well as doctrinally wrong.

Why would anyone embrace heresy?

You would think that someone would have to be out of their right mind to believe heresy. Who, after all, wants to believe something that isn't true? But, to quote Lucifer in Milton's Paradise Lost, the anthem of heresy is that ‘it is better to reign in hell than serve in heaven.’ Every heresy appeals to our sinful wishes and desires, the ‘way that we want things to be’ and not the way that God has provided in the gospel, ‘which is infinitely better for us’ as Bishop Allison put it. Consider all the major heresies and you will find that they appeal, directly or indirectly, to our sinful reason, affections and will. Heresy appears to be beneficial, posing as good news and proclaiming Jesus (2 Cor. 11:4), but in reality like gangrene it destroys spiritual life (2 Tim. 2:17).

Heresy always presents itself as an improvement on the biblical gospel. For the Colossians it promised to overcome their struggle with sin and bring them closer to God. For the Galatians it would keep them from persecution and fuel their desire to justify themselves before God by their works.

Heresy never appears in its true colors. In his monumental work Against Heresies Irenaeus wrote that ‘error, indeed, is never set forth in its naked deformity, lest, being thus exposed, it should at once be detected. But it is craftily decked out in an attractive dress, so as, by its outward form, to make it appear to the inexperienced (ridiculous as the expression may seem) more true than the truth itself.’

What are the effects of heresy?

Heresy brings confusion for unbelievers since they hear several different and contradictory voices all claiming to be telling them the authentic good news.

Heresy also brings trouble for the Church. Unless false teachers are silenced, as Paul tells Titus that they should be, they will ruin households and upset the faith of some (Titus 1:11). Genuine believers can be unsettled by the teaching of these men (2 Tim. 2:18). In addition to this damage, false teachers also drain the time, energy, and resources of churches when they are not dealt with. Drawn-out conflicts with false teachers can divert and distract gospel churches from evangelism and the planting and nurturing of new congregations.

Heresy places those who embrace it, and refuse to be corrected, in danger of eternal condemnation. At the very least the salvation of those who are deceived by gospel-denying error cannot be affirmed. There is hope that God may grant such people repentance. But the apostles did not shrink from spelling out the danger of turning to a ‘different gospel.’ Paul makes it clear that whether the ‘false brothers’, an angel from heaven, or even the apostles themselves preached another gospel than the one that Paul had preached then they should be accursed (Gal. 1:6-9).

Harold Brown summed up the consequences of truth and error by saying that ‘just as there are doctrines that are true, and that can bring salvation, there are those that are false, so false that they can spell eternal damnation for those who have the misfortune to be entrapped by them.’

Why do heresies persist?

Church history tells the story of the battle between truth and error. Heresies arise, gain a following, are opposed and refuted from Scripture, and then the Church moves on and advances in the truth. Because of this we have great statements like the Nicene Creed and the Definition of Chalcedon. But if these errors have been dealt with in the past why do they come back again and again? Why do people today believe old heresies? There are three reasons:

1. The devil still deceives people into believing heresies by using human instruments to promote attractive and plausible teaching. He will continue to do this until Christ returns in glory.

2. The warnings and lessons from history are ignored or unknown. If we are ignorant of the past we will fail to see that heresies that today appear new, innovative and interesting are as old as dirt. Many of the errors finding a home in evangelicalism today were tried and found wanting by our great-great-grandfathers in the faith at the bar of Scripture.

3. Throughout history those who deny the truth and choose a different gospel are limited in the options available to them. In his study of heresies Harold Brown concluded that ‘over and over again, in widely separated cultures, in different centuries, the same basic misunderstandings and misinterpretations of the person and work of Christ and His message reappear. The persistence of the same stimulus, so to speak, repeatedly produces the same or similar reactions.’

CHAPTER TWO

SIN

IN HIGH PLACES

An Interview with Carl R. Trueman

Carl R. Trueman is Professor of Historical Theology and Church History at Westminster Theological Seminary, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He is the author of The Wages of Spin, Minority Report, and John Owen: Reformed Catholic, Renaissance Man.

MARTIN DOWNES: As you reflect back on your student years and involvement in conservative evangelical organizations in the UK, were there men who started out with evangelical convictions who later moved away from the gospel? How did you cope with that?

CARL R. TRUEMAN: I always find it hard to speak or to write about such things. It is sad to see friends fall. Of course, I have known a few such figures; and, Martin, we have both worked together enough in the past to share a number of friends who are now nowhere in terms of orthodoxy and their Christian walk. In my experience, such friends and acquaintances have fallen into two broad categories. There are those who fell into serious immorality, homosexuality, adultery, bitterness of spirit, etc., and whose views seemed to shift almost as a result of the practical moral move, a way of getting out from under the demands of truth. Then there are a few who really do seem to be driven by intellectual crises and problems.

How have I coped? The fall of a friend or a respected mentor is hard to stomach; but there are a number of things which help us to understand these tragedies. I have a high view of human sin. I know that, left to themselves and placed in the perfect storm of circumstances, anyone is capable of anything. Remembering this basic fact means that, though we can be disappointed and surprised by individual falls, we should not see them as failures of the gospel but failures of sinful human nature. It is what I jokingly call Zen-Calvinism: once you are enlightened about and understand the universal power of sin, you can never be wrong-footed by the fall of another. Further, it should also prevent us from standing in pharisaic judgment on such friends. Sin needs rebuking and, if necessary, church discipline; but we do this in a spirit of love to God and out of a desire to see the fallen one restored.

I must say, I do feel great personal sadness and some responsibility when I think of particular friends who have fallen and not, so far, returned to the church. It is always sobering to ask ourselves if we have failed as Christian friends in such circumstances: could we have been more available? Should we have intervened at an earlier stage when we saw the start of a self-destructive path? Why were we not the kind of people to whom our friends were able to turn with their struggles and doubts? Did we preach the gospel to our friends as we should have done? There are names I won't mention of friends who have fallen and who will always lie somewhat heavy on my conscience. Of course, everyone must take responsibility for their own actions and thoughts, but such questions are helpful in preventing self-righteous smugness relative to the failings of others.

DOWNES: Have you ever been drawn toward any views or movements that time has shown to have been unhelpful or even dangerous theologically?

TRUEMAN: I dallied briefly with Barthianism and then with Berkouwer's theology in the late 1980s. Studying at the University of Aberdeen, I found the dominant theology to be Barthianism refracted through the writings of the Torrance brothers. Berkouwer's The Triumph of Grace in the Theology of Karl Barth was helpful in giving me a critical handle on Barth and helping to free me from that particular dead-end; and his Studies in Dogmatics also gave me an appreciation for doing theology in a self-consciously historical manner. However, as my knowledge of confessional Reformed Orthodoxy developed in the early 1990s, through reading widely in the primary texts and the relevant secondary literature, and as I came to grips with the wider sweep of Western theology as I had to teach courses on medieval thought and on Thomas Aquinas at the University of Nottingham, I began to see how Berkouwer too had absorbed a lot of Barth and how this distorted his reception of theological tradition. At that point, I started to develop a much more carefully worked out confessional theology.

In practice, the theologies of Barth and Berkouwer have really proved sterile as ecclesiastical programs. The best one can say is that they failed to stop the collapse of vital church life in Scotland, Germany, Switzerland, and the Netherlands. For all of their criticisms of the ‘static’ God of orthodoxy, Barthian preaching is, in my experience, sterile and dull, and fails miserably to confront listeners with the God of the Bible. I personally know of no church which has really grown through Barthian preaching.

So I would summarize by saying that I am very grateful to Barth and Berkouwer for directing me to serious dogmatics, for fuelling my interest in theology and doctrinal history, and for raising big and important questions in my mind; and I still enjoy reading them on occasion for the tremendous intellectual stimulation and challenge they provide; but I have ultimately found little of any real use, theological or practical, in the actual content of their theologies.

DOWNES: How should a minister keep his heart, mind and will from theological error?

TRUEMAN: No magic bullet here. The minister needs a good theological education, and then needs to maintain the basic disciplines of the Christian life – prayer and Bible reading, love to God and to neighbor. Of course, the minister does not sit under the preaching of the Word week by week, so accountability is even more of a problem for him than for others in the congregation. Presbyterianism has a structure of ministerial accountability in its church courts, but these are often impersonal and rather procedural gatherings. Even the Presbyterian minister still needs to make himself selfconsciously accountable to ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Dedication

- Endorsements

- Foreword

- Introduction

- 1. Heresy 101

- 2. Sin in High Places

- 3. In My Place Condemned He Stood

- 4. The Agony of Deceit

- 5. The Faithful Pastor and the Faithful Church

- 6. Truth, Error and the Minister's Task

- 7. The Defense Against the Dark Arts

- 8. Heroes and Heretics

- 9. The Good Shepherds

- 10. A Debtor to Mercy Alone

- 11. Truth, Error and the End Times

- 12. Fulfill Your Ministry

- 13. The Fight of Faith

- 14. Raising the Foundations

- 15. Teaching the Whole Counsel of God

- 16. Present Issues from a Long Term Perspective

- 17. Ministry Among Sheep and Wolves

- 18. Error and the Church

- 19. Will the Church Stand or Fall?

- 20. The Annihilation of Hell

- 21. The Word of Truth

- 22. Being Against Heresies Is Not Enough

- 23. Clear and Present Danger

- Author